| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER II.

Objects in

visiting China My boat and boatmen A

groundless alarm Chinese pilgrims Chair-bearers Road to Ayuka's

temple

Crowds by the way Shyness of ladies Description of scenery Wild

flowers

Tea-farms Approaches to temple Ancient tree Hawkers and their

stalls

Scene in temple Visit to high priest Shay-le or precious relic

Its

history and traditions A picnic Character of the people for

sobriety An

evening stroll The temple at night Huge idols Queen of Heaven and

child

Superstitions of Chinese women.

MY chief object in coining to

China at this time was

to procure a number of first-rats black-tea manufacturers, with large

supplies

of tea-seeds, plants, and implements, such as were used in the best

districts,

for the Government plantations in the north-west provinces of India.

Leaving

Taiping-Wang to fight his battles in the province of Kiang-su and

elsewhere, I

sailed for the town of Ningpo in the province of Chekiang, and on my

arrival at

that port started immediately for the tea districts in the interior. I

had

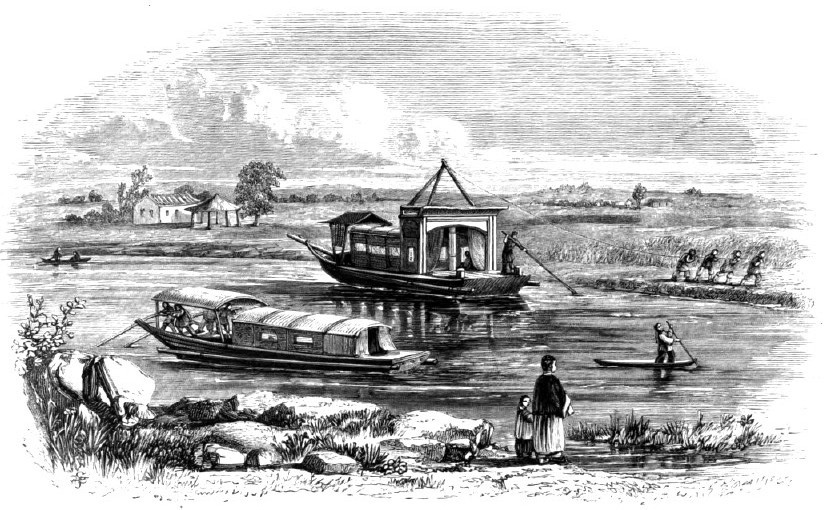

engaged a small covered boat, such as is used on the canals in this

part of the

country. It was divided into three compartments: that in the stern was

occupied

by the boatmen, who propelled the boat by a powerful scull, which

worked on a

small pivot; the centre was occupied by myself, and the forepart by my

servants. The length of time these boatmen are able to work this scull

is very

extraordinary. It is customary with them to go on continually both day

and

night, from the commencement

of a journey until

its end. When working in rivers, when it is calm, or when the wind is

a-head,

they have to anchor when the tide is against them, and in this way rest

for six

hours at a time; but in canals, when the tide is not felt, they go on

always

both night and day. And what is more wonderful still, the greater part

of the

work is done by one, and that one is oftentimes a mere boy. The boatman

in each

boat is generally the owner, and the boy is engaged by him to assist in

the

working of the boat. Hence the former is the master and the latter the

man; and

as a matter of course the man has to do the greater part of the work.

But these

boys are well fed and kindly treated by their masters, and they seem

happy and

contented with their lot in life. This continual working with the scull

seems

to unfit them for any other kind of work; when on shore they walk badly

with a

sort of rolling motion, much worse than that of a common sailor, and

seem

altogether like a "fish out of water." The distance from the city of

Ningpo to the end of

the canal and foot of the hills to which I was bound was about ten or

twelve

miles. As we had travelled all night we reached the end of the canal

some time

before daybreak. I had slept pretty well on the way, but was now

awakened by

the sounds of hundreds of voices, some talking, others screaming at

their

loudest pitch, and the shrill tones of the women were heard far above

those of

the men. Half-awake as I was at first, I almost thought I had fallen in

with a

party of Tai-ping-Wang's army; but my servants and the boatmen soon set

me

right on that point, by informing me the multitudes in question were on

their

way to Ah-yuh-Wang, or Ayuka's temple, to worship and burn incense at

its

shrines. To fall asleep again was now out of the question, owing to the

noise

and excitement by which I was surrounded. I therefore got up and

dressed, and

took a seat on the roof of my boat, when I had a moonlight view of what

was

going on around me. Every boat seemed crowded with pilgrims, the

greater part

by far consisting of well-dressed females, all in their holiday attire.

As

daylight dawned the view became more distinct. Each boat was now

brought close

to the banks of the canal, in order that the

passengers might be able to get on shore. I pitied the ladies, poor

things!

with their small cramped feet, for it was with great difficulty they

could walk

along the narrow plank which connected the boat with the bank of the

canal. But

the boatmen and other attendants were most gallant in rendering all the

assistance in their power, and the fair sex were for the most part

successful

in reaching "terra firma" without any accident worth relating.

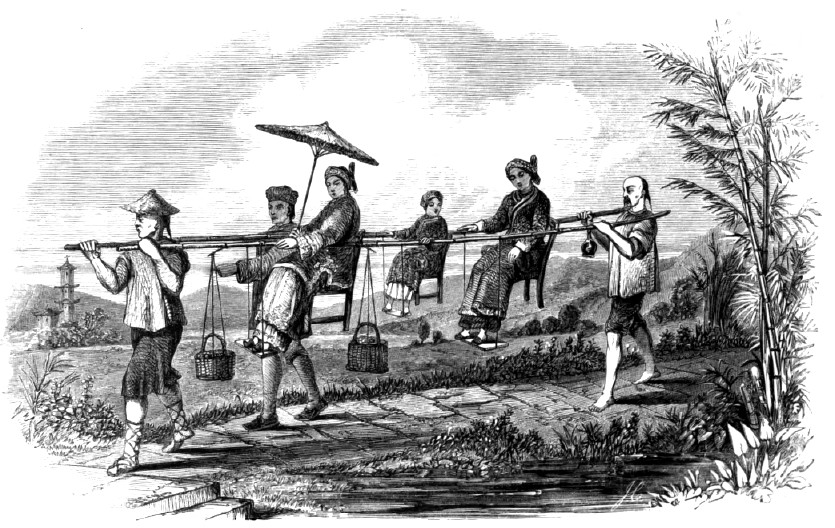

Numerous chair-bearers and chairs lined the banks of the

canal, all anxious for

hire; and if the more

wealthy-looking did not get conveyances of this kind, it certainly was

not the

fault of the owners of these vehicles, for they were most importunate

in their

offers. Indeed so much was this the case, that in many instances under

my

observation the wavering pilgrim was almost lifted into the chair

before he was

aware of it. These chairs are extremely light and simple in their

construction.

They are formed of two long bamboo poles, with a small piece of wood

slung

between them, on which the traveller sits, and another smaller piece

slung

lower and more forward, on which he rests his feet. Sometimes, when

ladies and

children were to be carried, and the weight consequently light, I

observed two

or three of these seats slung between the poles, and this number of

persons

carried by two stout coolies with the greatest ease.

After taking my morning cup of

tea within sight of

numerous plantations of the "herb" itself, which are dotted on the

sides of the hills here, I joined the motley crowd, and proceeded with

them to

Ayuka's temple. When I got outside of the little village at the end of

the

canal, and on a little eminence beyond it, I obtained a long view of

the

mountain-road which leads to the temple. And a curious and strange view

this

was. Whether I looked before or behind me, I beheld crowds of people of

both

sexes and of all ages, wending their way to worship at the altars of

the

"unknown God." They were generally divided into small groups little

families or parties as they had left their native villages, and most

of these

parties had a servant or two walking behind them, and carrying some

food to

refresh them by the way, and a bundle of umbrellas to protect them from

the

rain. Each of the ladies young and old who were not in chairs,

walked with

a long stick, which was used partly to prevent her from stumbling, and

partly

to help her along the road. Most of them were dressed gaily in silks,

satins,

and crapes of various colours, but blue seemed the favourite and

predominating

one. As I walked onward and passed group after group on the way, the

ladies, as

etiquette required, looked demure and shy, as if they could neither

speak nor

smile. Sometimes one past the middle age would condescend to answer me

goodhumouredly; but this was even rare. The men on the contrary were

chatty

enough, and so were the ladies too as soon as I had passed them and

joined

other groups farther a-head. Oftentimes I heard a clear ringing laugh,

after I

had passed, from the lips of some fair one who but a minute before had

looked

as if she had never given way to such frivolity in her life. But while I am still on a little

eminence from which

I have been viewing man, let me turn to the other and not less

beautiful works

of nature. Behind me lay a large and fertile valley, the same through

which I

had passed during the night, intersected in all directions with

navigable

canals, and teeming with an industrious and happy people. As it was now

"the bonnie month of May," the rice crops had been some time in the

ground, and the valley was consequently covered with dense masses of

the

loveliest green. Waterwheels were observed in all directions, some

worked by

men, and other and larger ones by bullocks, and all pouring streams of

water

upon the rice crops from the various canals which intersect the valley.

At the

foot of the hills near where I stood were numerous small tea-farms,

formed on the

slopes, while groups of junipers and other sombre-looking pines marked

the last

resting-places of the wealthy. The ancient tombs of the Ming dynasty

are also

common here, but they are generally in a ruinous condition; and had it

not been

for the huge blocks of granite cut into the forms of men and other

animals, of

which they are composed, there would have been long ago no marks to

point out

the last resting-places of these ancient rulers of China. So much for

human

greatness! Higher up on the hill-sides the ground was cultivated and

ready to

receive the summer crops of sweet potatoes and Indian corn. Beyond that

again

were barren mountains covered with long grass and brushwood, which the

industry

of the Chinese is never likely to bring under cultivation. Both below

and

above, on the roadsides, in the hedges, and on every spot not under

cultivation, wild flowers were blooming in the greatest profusion. In

the

hedges the last fading blossoms of the beautiful spring-flowering Forsythia

viridissima were still hanging on the bushes, while several

species of wild

roses, Spirζa Reevesiana, clematises, and Glycine

sinensis, were

just coming into bloom. But look a little higher up to that gorgeously

painted

hill-side, and see those masses of yellow and white flowers; what are

they? The

yellow is the lovely Azalea sinensis, with its

colours far more

brilliant, and its trusses of flowers much larger, than they are ever

seen in

any of our exhibitions in Europe. The white is the little-known Amelanchier

racemosa. Amongst these, and scattered over the hill-sides,

are other

azaleas, having flowers of many different hues, and all very beautiful.

It is

still early morning; the sun is just appearing on the tops of the

eastern

mountains; the globules of heavy dew sparkle on the grass and flowers;

the lark

and other sweet songsters of the feathered race are pouring out of

their little

mouths sweet and melodious songs. I looked with delight on the

beautiful scene

spread out before me, and thought within myself, if Nature is so

beautiful now,

what must it have been before the Fall, when man was holy!

As I approached Ayuka's temple I

observed other roads

leading to the same point, crowded with people such as I have already

described, all hurrying on to pay their vows at the altars of Buddha.

The

scenery in front of the temple, although in a ruinous condition now, at

some

former time was no doubt very pretty. Entering through an ancient

gateway, a

paved path led straight up to the edifice, over an ornamental bridge,

which at

one time probably spanned the neck of a small lake, in which was

cultivated the

sacred lotus (Nelumbium speciosum), but which was

now in these

degenerate days allowed to get choked up with weeds. Near this bridge a

noble

specimen of the camphor-tree (Laurus camphora) lay

prostrate on the

ground, having been blown down by a typhoon many years ago. The curious

gnarled

and angular branches for which this tree is remarkable when it is alive

and

standing, seemed more striking in its prostrate and withered condition.

For many

years this relic of former days had been carefully preserved by the

priests,

and was now looked upon by them and the visitors as nearly as holy as

the

temple itself. From the gateway up to the doors of the temple numerous

stalls

were erected for the sale of candles, joss-sticks, sycee paper, and

such things

as are used in the worship of Buddha. Others were of a less holy

character, and

contained cakes and sweetmeats, toys, curiosities, and things likely to

attract

the notice of the country people. It was curious to mark the enthusiasm

with

which these pedlers endeavoured to get off their goods. Every passer-by

was

pressed to buy, and particularly those who had not their hands full of

candles,

incenses, and other articles which they were supposed to require. In

many

instances I observed the venders actually laid hold of the people, and

almost

forced them to spend money on some articles ere they would allow them

to go on.

Of course this was done in the most perfect good humour. These pedlers

are

first-rate physiognomists; they know at a glance those who are likely

to become

customers, and, should the slightest hesitation be visible on any

countenance,

that man is doomed to spend his money ere he passes the stall. I now entered the temple itself,

and found it crowded

with idolaters. The female sex seemed much more numerous than the male,

and

apparently more devout. They were kneeling on cushions placed in front

of the

altars, and bowing low to the huge images which stood before them. This

prostration they repeated many times, and when they had finished this

part of

their devotions they lighted candles and incense, and placed them on

the

altars. Returning again to the cushion, they continued their

prostration for a

few seconds, and then gave way to other devotees, who went through the

same

forms. Some were appealing directly to the deity for an answer to their

petitions by means of two small pieces of wood, rounded on the one side

and

flat on the other. If on being thrown into the air the sticks fell on

the flat

side, they had then an assurance of a favourable answer to their

prayers; but

owing to the laws of gravitation these stubborn little bits of wood

fell much

oftener on the rounder and heavier side than on the other, and gave the

poor

heathen a world of anxiety and trouble. Other devotees were busily

engaged in

shaking a hollow bamboo tube which contained a number of small sticks,

each

having a Chinese character upon it. An adept in shaking can easily

detach one

of these sticks from the others, and when it falls upon the floor it is

picked

up and taken to a priest, who reads the character and refers to his

book for

the interpretation thereof. A small slip of paper is now given to the

devotee,

which he carries home with him, and places in his house or in his

fields, in

order to bring him good luck. I observed that not unfrequently it was

very

difficult to satisfy these persons with the paper given to them by the

priest,

and that they often referred to those who were standing around, and

asked their

opinion on the matter. The scene altogether was a

striking one, and was well

calculated to make a deep impression on the mind of any one looking on

as I

was. Hundreds of candles were burning on the altars, clouds of incense

were

rising and filling the atmosphere; from time to time a large drum was

struck

which could be heard at a distance outside the building; and bells were

tinkling and mingling their sounds with those of the monster drum. The

sounds

of many of these bells are finer than anything I ever heard in England.

Most of

the fine ones are ancient, and were made at a time when the arts ranked

higher

in China than they do at the present day. In the midst of all these

religious services, which

candour compels me to say were outwardly most devoutly performed,

things were

going on amongst the worshippers which as foreigners and Christians we

cannot

understand. Many, who had either been engaged in these ceremonies or

intended

to take their part in them, were sitting, looking on, and laughing,

chatting,

or smoking, as if they had been looking on one of their plays. And it

was not

unusual to see a man fill his pipe with tobacco, and quietly walk up

and light

it at one of the candles which were burning on the altar.

After looking on this curious

and noisy scene for a

little while, I was glad to leave it for the quieter parts of the

building. I

went in the first place to pay my respects to the high-priest, and

found him

occupying some small rooms built at one side of the large temple. With

Chinese

politeness he received me cordially and made me sit down on the seat of

honour

in his little room. A little boy who served him brought in a tray, on

which a

number of teacups were placed filled with delicious tea. Two1

of

these cups were put down before me, and I was pressed to "drink tea."

As the day was excessively warm, the pure beverage was most welcome and

refreshing. Reader, there was no sugar nor milk in this tea, nor was

there any

Prussian blue or gypsum; but I found it most refreshing, for all that

it lacked

these civilised ingredients. The good old man was

very chatty, and gave

me a great deal of information about himself and the temple. The

revenues of

the temple were derived partly from certain lands in the vicinity which

belonged to it, and partly from the contributions of devout Buddhists

who came

there to worship. The high-priest himself also contributed largely to

its

support. On inquiring how this happened, he informed me that he was

obliged to

contribute a large sum I think he said 3000 dollars before he could

be

elected to the office he now held, and that he held it for three years

only,

when his successor would have to contribute a similar sum. This sum was

spent

in keeping the temple in repair. I understood him to say that the

inducement

held out to men of his class is high honours at the end of the three

years when

they retire into private life. When we had sipped our tea, I

then told the

high-priest I had heard there was a Shay-le or

relic of Buddha in the

monastery, and expressed a desire to see it. He appeared pleased to

find the

fame of the relic had reached my ears, and sent immediately for the

priest

under whose charge it was placed, and desired him to show it to me. I

now bade

adieu to the old man, and followed my guide to that part of the

monastery where

the relic was kept. On our way he asked me whether it was my intention

to burn

incense to Buddha before the box which contained the relic was opened.

I

replied that not being a Buddhist I could not do that, but I would give

him a

small present for opening the box a way of settling the question

which seemed

to please him quite as well as buying candles and incense to burn at

the

shrine. I found the precious relic locked up in a bell-shaped dome.

When this

was opened I observed a small pagoda carved in wood, and evidently very

ancient. It was about ten inches or a foot in height, and four inches

in width.

In the centre was a small bell, and near the bottom of this the shay-le

or

relic was said to be placed. "I can see nothing there," said I to my

guide.

"Oh," said he, "you must get it between you and the light, and

then you may see it; it is sometimes very brilliant, but only to those

who

believe." "I am afraid it will not shine for my gratification

then," said I; but I stood in the position my guide indicated. It might

be

imagination, I dare say it was, but I really thought I saw something

unusual in

the thing, as if some brilliant colours were playing about it. The

Reverend Dr.

Medhurst, of the London Missionary Society, who has since visited and

examined

the relic, could see nothing "because he had no faith;" and if at any

time there is anything to be seen, such an appearance could no doubt be

easily

explained from natural causes. The priest informed me the precious

relic had

been obtained from the top of a hill behind the temple by their

forefathers,

who had handed it down with the traditions attending it to the present

generation, and that they wanted no further proof of its being genuine. Shay-le, or precious relics of

Buddha, are found in

many of the Buddhist temples. In a former work 2 I have described two in

the celebrated

monastery of Koo-shan, near Foo-chow-foo in Fokien. In a note published

by the

Reverend Dr. Medhurst the history of such relics is given by the

Chinese in the

following manner: "The Buddhists say there are 84,000 pores in a

man's

body, and thus, by following corruption and passing through

transmigration, he

leaves behind him 84,000 particles of miserable dust. Buddha's body has

also

84,000 pores, but by resisting evil and reverting to truth he has

perfected

84,000 relics; these are as hard and as bright as diamonds, affording

benefit

to men and devas wherein they are deposited. * * * * Eight kings

contended for

these relics, which were divided into three parts, one being assigned

to the

devas, one to the nagas, and the third to the eight kings. During

Buddha's

lifetime he was begging with O-nan in a lane, when they saw two boys

playing

with earth; one of them, being struck with the dignified appearance of

Buddha,

presented him with some pellets of earth, expressing a wish at the same

time

that he might in future become one of his most zealous worshippers.

Buddha then

addressed O-nan, saying, 'After my obtaining nirvaan

(nothingness, i.e.

death), this child will become a king, ruling over the southern

kingdoms, and

building pagodas for the preservation of my relics.' This was Ayuka,

who

afterwards built 84,000 pagodas; nineteen of these were constructed in

China,

and one of them was fixed on the snow-hill in the prefecture of Ningpo,

commonly called Yuh-wong. About the time of the Three Kingdoms (A.D.

230) a

priest named Hwuy came to Nanking, where he built a shed. The people

thought

him a strange being, and brought him to Sun-keuen, the ruler of the

country,

who asked him for the proofs of his religion. Hwuy replied that Buddha

left a

number of relics, over which Ayuka had built 84,000 pagodas. Sun-keuen

thought

it was all nonsense, and told him that if he could find a relic he

might build

a pagoda over it. Hwuy then filled a bottle with water, and offered up

incense

before it for twenty-one days; at the expiration of that period he

heard a

sound proceeding from the bottle resembling that of a bell. Hwuy then

went to

look at it, and perceived that the relic was formed. The next day he

presented

it to Sun-keuen; the whole of the courtiers examined it, and saw the

bottle

illuminated with all sorts of brilliant colours. Keuen took the bottle,

and

poured out its contents into a dish; when the relic came in contact

with the

dish it broke the vessel to pieces. Keuen was astonished and said,

'That is

very curious.' Hwuy then addressed him, saying, 'This relic is not only

capable

of emitting light, but no fire will burn, nor diamond-headed hammer

bruise it.'

He then placed the relic on an anvil, and caused a strong man to strike

it with

all his might, when the hammer and anvil were both broken, and the

relic

remained uninjured. Keuen then assented to the construction of the

pagoda. The

Chinese say that they can sometimes discern the relic illumined with

brilliant

colours, and as big as a cart-wheel, while the unbelievers can see

nothing at

all." Such are the Chinese traditions

concerning these

so-called precious relics of Buddha, which one meets with so frequently

in

Buddhist temples, not only in China, but also in India.

After inspecting this precious

relic I returned

through the various temples, which were still crowded with worshippers,

to the

open air. As the day was warm, I sought shelter from the scorching rays

of the

sun in a little wood of bamboos and pines which was close at hand. Here

I mixed

with groups of worshippers who were now picnicking under the shade

which the

trees afforded. Each little group had brought its own provisions, which

appeared to be relished with great zest. In many instances I was asked

to join

with them and partake of their homely fare, an invitation which I

declined, I

trust, in as polite a manner as that in which it was given. Many of

them seemed

weary and footsore with their long journey, but all were apparently

happy and

contented, and during the day I did not observe a single instance of

drunkenness or any disturbance whatsoever. The Chinese as a nation are

a quiet

and sober race: their disturbances when they have them are unusually

noisy, but

they rarely come to blows, and drunkenness is almost unknown in the

country

districts, and rare even in densely populated cities. In these respects

the

lower orders in China contrast favourably with the same classes in

Europe, or

even in India. When the sun had got a little to

the westward, and

his rays less powerful, I left the temple and took my way to the hills.

In a

few minutes that busy scene of idol-worship which I have endeavoured to

describe was completely shut out from my view. As I went along I came

sometimes

unexpectedly on a quiet and lonely valley where the industrious

labourers were

busily at work in the fields, or on a hill-side where the natives were

gathering their first crop of tea. Here is no apparent want, and

certainly no

oppression; the labourer is strong, healthy, and willing to work, but

independent, and feels that he is "worthy of his hire." None of that

idleness and cringing is here which one sees amongst the natives of

India, for

example, and other eastern nations. Time passed swiftly by when

wandering amongst such

interesting scenery, and as evening was coming on I returned to the

temple, in

which I proposed taking up my quarters for the night. Now the scene had

entirely changed: the busy crowds of worshippers were gone, the sounds

of bell

and drum had ceased, and the place which a short time before was

teeming with

life was now as silent as the grave. The huge idols many of them full

thirty

feet high looked more solemn in the twilight than they had done

during the

day. The Mahβrβjas, or four great

kings of Devas, looked

quite fierce; Me-lie-Fuh, or the merciful one,

a stout,

jovial-looking personage, always laughing and in good-humour, seemed

now to

grin at me; while the three precious Buddhas, the past, present, and

future,

looked far more solemn and imposing than they usually do by day. The

Queen of

Heaven (Kwan-yin), with her child in her arms, and with rocks, clouds,

and

ocean scenery in the background, rudely carved in wood and gaudily

painted, was

the only one that did not seem to frown. What a strange representation

this is,

rude though it be! some have supposed that this image represents the

Virgin

Mary and infant Saviour, and argue from this that Buddhism and

Christianity

have been mixed up in the formation of the Buddhist religion, or that

the

earlier Buddhists in Tibet and India have had some slight glimmerings

of the

Christian faith. The traveller and missionary M. Huc is, I believe, of

this

opinion. At first sight this seems a very plausible theory, but in the

opinion

of some good Oriental scholars it is not borne out by facts. The

goddess is

prayed to by women who are desirous of having children, and she holds

in her

arms a child which she seems in the act of presenting to them in answer

to

their petitions. Chinese ladies have curious prejudices on this

subject: they

imagine that by leaving their shoes in the shrine of the goddess they

are the

more likely to receive an answer to their prayer. Hence it is not

unusual to

see a whole heap of tiny shoes in one of these shrines. In former days

the

custom of throwing an old shoe after a person for luck was not unusual

in

Scotland, and may have been introduced from that ancient country to

China or vice

versα.

1 The

Chinese generally place two cups before a stranger.

2 Journey

to the Tea Countries of China and India. |