| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER IV.

Entomology Chinese ideas

respecting my collections My

sanity doubtful Mode of employing natives to assist me A scene on

returning

to my beat Curious tree Visit from a mandarin An endeavour to

explain my

objects in making collections of natural history Crowds of natives

Their

quietness and civility Return mandarin's visit My reception

Example of

Chinese politeness Our conversation Inquisitiveness of his ladies

and its

consequences Beauty of ladies at Tse-kee Our luncheon and

adieu.

THE hilly districts amongst which I was

now

sojourning were particularly rich in beautiful and rare insects. A

small

bottle, an insect-box, and a net were continually carried both by

myself and

men, and many were the fine things we captured, as the cabinets of most

of the

entomologists in Europe can now testify. This proceeding seemed to

astonish the

northern Chinese beyond measure, and, from the mixture of awe and pity

depicted

in many a countenance, they evidently thought me a little cracked in

the head.

The more intelligent amongst them believed I was collecting for medical

purposes,

and that all my specimens were destined to be chopped up in a mortar

and made

into pills to be swallowed by the sick. The Chinese have not the

slightest idea

of the study of entomology, and laughed at me when I attempted to

explain to

them that insects are collected for such a purpose. Their medicinal

value

seemed to them a much better reason for the trouble of collecting.

Amongst

themselves an idea is prevalent that the larva of coleopterous and

other

insects form excellent food to give occasionally to young children, and

hence

in my rambles I met not unfrequently persons employed in collecting

larva for

this purpose. A species of toad, found in the rotten hollow trunks of

trees

during the hot months, is eagerly sought after by the young men in the

army who

are being trained to the use of the bow, and to whose bones and sinews

it is

supposed to give additional strength. This strange-looking animal sells

in the

market at from fourpence to eightpence each, but it is extremely rare. The children in the different villages

were found of

the greatest use in assisting me to form these collections, and the

common

copper coin of the country is well adapted for such purposes. One

hundred of

this coin is only worth about fourpence-halfpenny of our money, and

goes a long

way with the little urchins. A circumstance connected with transactions

of this

kind occurred one day, which appears so laughable that I must relate

it. As I

went out on my daily rambles I told all the little fellows I met that I

would

return in the evening to the place where my boat was moored, and, if

they

brought me any rare insects there, I would pay them for them. In the

evening,

when I returned and caught a glimpse of my boat, I was surprised to see

the

banks of the stream crowded with a multitude of people of all ages and

sizes

old women and young ones, men and boys, and infants in arms were

huddled

together upon the bank, and apparently waiting for my return. At first

I was

afraid something of a serious nature had happened, but as I came nearer

I

observed them laughing and talking good-humouredly, and guessed from

this that

nothing had gone wrong. Some had baskets, others wooden basins, others,

again,

hollow bamboo tubes, and the vessels they carried were as various in

appearance

as the motley group which now stood before me. "Mβ jung! mβ jung!"

(buy insects! buy insects!) was now shouted out to me by a hundred

voices, and

I saw the whole matter clearly explained. It was the old story, "I was

collecting insects for medicine," and they had come to sell them by the

ounce or pound. I had unintentionally raised the population of the

adjoining

villages about my ears; but having done so, I determined to take

matters as

coolly as possible, and endeavour either to amuse or pacify the mob. On

examining

the various baskets and other vessels which were eagerly opened for my

inspection, what a sight was presented to my view! Butterflies,

beetles,

dragonflies, bees legs, wings, scales, antennae all broken and

mixed up in

wild confusion. I endeavoured to explain to the good people that my

objects

were quite misunderstood, and that such masses of broken insects were

utterly

useless to me. "What did it signify they were only for medicine, and

would have to be broken up at any rate." What with joking and reasoning

with them, I got out of the business pretty well. As in all cases I

found the

women most clamorous and most difficult to deal with, but by showing

some

liberality in my donations of cash to the old women and very young

children I

gradually rose in their estimation, and at last, it being nearly dark,

we

parted the best of friends. I have been placed in circumstances

somewhat

similar on various occasions since, but I have hitherto managed to come

safely

out of the scrape. Sometimes amongst all this chaff there were grains

of wheat,

and not the least striking was a beautiful species of Carabus (C.

coelestis),

which was brought to me at this time, and for which I gave the lucky

finder the

large sum of thirty cash, with which he scampered off home, delighted

with his

good luck. Paying away sums like this for insects seemed to confirm the

natives

in the views they had originally formed respecting my character. The

Chinese,

however, are as a people eminently practical in all their views, and it

mattered not to them whether I was sane or not so long as they got the

cash.

They now set to collecting in all directions, and brought me many fine

things.

On returning home to my boat in the evenings I was called to from every

hill-side, "Mβ jung! mβ jung!" (buy insects! buy insects!) and then

the little fellows were seen bounding down towards the road on which I

was

walking. This distribution of cash amongst the children soon made me

quite a

favourite with their parents, and in my walks in the country I was

invited into

their houses, where I received much kindness and hospitality. The

poorest

cottager had always a cup of tea for me, which he insisted on my

sitting down

and drinking before I left his house. Before leaving this part of the

province

I distributed a number of bottles, each being about half filled with

the strong

spirit of the country (samshoo). These were given to those who promised

to make

collections for me during my absence; they were told to throw the

insects into

the spirit when caught, and let them remain until I came to claim and

pay for

them. By this means I was able to add many novelties to my collection

when I

again visited Tse-kee in the autumn, to form my other collections of

plants and

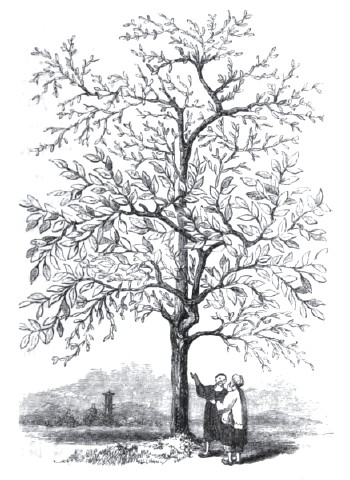

seeds. On one of my excursions amongst these

hills I met

with a curiously-formed tree, which at first sight seemed to confirm

the old

Virgilian tale of apples growing upon plane-trees. It was one of those

junipers

(J. sphζrica) which grow to a considerable size in the north of

China,

and which the Chinese are fond of planting round their graves. But

although a

juniper at the top and bottom, an evergreen tree with large glossy

leaves (Photinia

serrulata) formed the centre. On reaching the spot where it grew,

the

appearance presented was, if possible, more curious and interesting.

The

photinia came out from the trunk of the juniper about 12 feet from the

ground,

and appeared as if it had been grafted upon it; indeed, some Chinese in

a

neighbouring village, to whom the tree was well known, did not hesitate

to express

their belief that such had been the case, but I need scarcely say this

was out

of the question. Upon a close examination of the point of apparent

union, I

found that, although the part between stock and graft, if I may use the

expression, was completely filled up, yet there was no union such as we

see in

grafted trees. There could then be only one way of accounting for the

appearance which these two trees presented, and which is pretty well

shown in a

drawing taken by a Chinese artist. The photinia was no doubt rooted in

the

ground, and had 12 feet of its stem cased in the decayed trunk of the

juniper.

The apparent union of the trees was so complete, that nothing could be

seen of

this arrangement; but upon tapping the lower part of the trunk it

sounded hollow,

and was no doubt decayed in the centre, although healthy enough outside. Upon showing the accompanying sketch to a

learned

Chinese, the teacher of Mr. Meadows, at Ningpo, he, like the villagers,

fully

believed the photinia had been grafted upon the juniper; and further,

he

informed me it was a common thing in the country to graft the Yang-mae (Myrica

sp., a fine Chinese fruit-tree) upon Pinus sinensis, and that

by so

doing the fruit of the Yang-mae became much larger and finer in

flavour. Having

been engaged in procuring some Yang-mae trees, which the Government of

India

was anxious to introduce to the Himalaya, I was somewhat better

informed upon

this subject than the learned Chinaman. I told him the fine

variety of

Yang-mae was grafted upon the wild kind, which the Chinese call the San

or hill

variety (Myrica sapida); and further, I showed him some plants

which I

had just purchased: but all was of no use; he was "convinced against

his

will," and still firmly believes the Yang-mae is usually grafted on the

pine.  Remarkable tree. Travelling as I was all alone, and engaged

in making

collections of natural history, the objects of which the natives could

not

comprehend, it was not to be wondered at if my fame was spread far and

wide

over the country. I had visits from several mandarins and other wealthy

inhabitants of the district, and the way in which some of the more

timid of

these gentry presented themselves was to me highly amusing. One day,

when I was

busy in arranging my collections, I heard a stranger's voice calling my

servant, and on looking out at the window I observed a

respectable-looking man

with several attendants within a few yards of my boat. From his manner

he was

evidently most anxious to see me and what I was after, but at the same

time he

seemed doubtful of the reception I might give him. My servant having

assured

him that I was perfectly harmless, he mustered courage at last to come

alongside. In the mean time I opened the boat, and invited him to come

inside.

I suppose my appearance and manners must have been more favourable than

he had

been led to expect by the report which had reached his ears, for he

immediately

made me a most polite bow, and accepted my invitation. When I spread

out my

entomological collections for his inspection, he seemed perfectly

astonished.

"Did you really get all these in this district?" said he.

"Strange, that, although I am a native, yet there are hundreds of them

I

have never seen before." I ventured to hint that perhaps he had not

looked

for them, which he said was very true, and no doubt accounted for his

not

having seen them. As my boat was made fast to the bank of the canal, we

were

surrounded by crowds of the natives, who, hearing that I was showing my

collections to the mandarin, were all anxious to have a peep. Hundreds

of

questions were put to each other on all sides as to what I could

possibly be

going to do with the numerous strange things which I had got in my

boxes. The

more wise amongst the crowd informed the others that all the insects

were collected

to be made into medicine, but as to the diseases which they were

destined to

cure, the wisest amongst them were obliged to plead ignorance. My

servants and

boatmen were often appealed to for light upon the subject, but they

only

laughed and confessed their entire ignorance; nor did they take the

slightest

trouble to convince their countrymen that they were wrong in their

conjectures. When I had shown my collections to my

visitor, he put

the question which the crowd had been discussing outside, and which

discussion

he had heard as much of as I had done. Had I entered into the merits of

the

study of entomology, he most certainly would not have been able to

bring his

mind to believe I was telling him the truth. If, on the other hand, I

had told

him I intended to make medicine of my collections, although he would

have

believed me, yet this would have been untrue. So I thought I might give

him

another idea which he would comprehend and appreciate. "In my own

land," said I, "many thousand le from this, we have a great

and good Queen who delights in the welfare and happiness of her people.

For

their instruction and amusement a large house1 has been

constructed

far larger than any of your temples or public buildings which have

come under

my observation and into this house have been brought many thousands

of plants

and animals collected in every country under heaven. Here each species

is

classified and named by scientific men appointed for the purpose, and

on

certain days in every week the doors are thrown open for the admission

of the

public. Many thousands avail themselves of these opportunities, and

thus have

the means of studying at home the numerous forms of animals and plants

which

are scattered over the surface of the globe. Many of the insects and

shells

which you see before you are destined to form a part of that great

collection,

and thus persons in England who are interested in such things will have

the

means of knowing what forms of such animals exist in the hills and

valleys

about Tse-kee." My visitor seemed much interested with the information

I

gave him, and, although he did not express any surprise, I trust he

received a

higher idea of our civilisation than he had entertained before. What

surprised

him more than anything else was my statement that a Queen was the

sovereign of

England. I have often been questioned

as to the truth of this by the Chinese, who think it passing strange,

if it be

really true. Before taking his leave he gave me a

pressing

invitation to pay him a visit at his house in the city on the following

day, or

on any day it might be convenient for me. I promised to do so, and got

my

servant to take down his address, in order that we might not have any

difficulty in finding his house. The door of the boat was now thrown

open, and

I handed him out to the banks of the canal. Here we made most polite

adieus in

the most approved Chinese style, in the midst of a dense crowd, who had

been

attracted by the rank of my visitor, and partly perhaps by the reports

which

had been spread about myself. The crowd which had now collected was of a

mixed

character; but owing, I suppose, to the number of wealthy and

respectable

people in the city, the individuals were generally well-dressed and

clean, and

perfectly respectful and civil in their demeanour. Applications were

made to me

on all sides for permission to enter the boat and inspect my

collections. This

being entirely out of the question, I had a portion of the cover

removed in

order that their curiosity might be satisfied from the banks of the

canal.

Entering the boat myself, I opened box after box, and spread out my

collections

before them. My table, bed, the floor of the boat, and every inch of

space was

completely covered with examples of the natural history of the place.

"Can

all these things have been collected here?" was on every lip; "for

many of them we have never seen, although we are natives of the place

and this

is our home." And when I pointed out some of the more remarkable

amongst

the insects, and gave them the names by which they are known to the

natives, I

was complimented and applauded on all sides. "Here," said I, for

example, "is a beautiful Ka-je-long (carabus), which I am

anxious

to get more specimens of; if you will bring some to me I shall pay you

for

them. That Kin Jung (golden beetle) you need not collect, for it is

common in

every hedge." "Oo-de-yeou?" Do you want butterflies?

"No," I replied, "for you cannot catch them without breaking

them." And so the conversation went on, every one being in the best

possible humour. When I had shown them the greater portion of my

collections,

the cover of the boat was let down, and everything put away into its

proper

place. I was now anxious to disperse the crowd, and for that purpose

informed

them that, as the afternoon was getting cool, I was now going out to

make

further additions to my collections. "Thank you, thank you," said

many of them, making at the same time many most polite bows after the

manner of

the country, which I did not fail to return. And so we parted the best

of

friends. When I returned from my excursion it was nearly dark; the

crowd had

all gone to their homes, and quietness now reigned where all had been

noise and

bustle a few hours before. One or two little boys were sitting on the

banks of

the canal waiting my arrival, in order to dispose of some insects which

they

had been lucky enough to capture during the day. And so I went on from

day to

day, gradually increasing my collections, with the help of hundreds of

little

boys, who were delighted to earn a few "cash" so easily. The effect

produced upon the villagers was also most marked, and I was welcomed

wherever I

went, and everywhere invited to "come in, sit down, and drink tea."

This picture is not very like many which have been given of China and

the Chinese,

but it is true to nature nevertheless. I trust it may give a higher

idea of the

civilisation of this people than we are accustomed to form from the

writings of

those whose principal knowledge was derived from views at the great

southern

seaports of the empire. The day after that on which I had been

honoured with

a call from the mandarin, I dressed with more than ordinary care, sent

for a

sedan-chair, and set out to return his visit. When I arrived at his

house I

found that he was expecting me. He was dressed in a long gown, bound

round the

waist with a belt which had a fine clasp made of gold and jade-stone,

and on

his head was a round hat and blue button. He received me with many low

bows in.

the Chinese manner, which I returned in the same way. He then led me

into a

large hall, and invited me to take the seat of honour. In all the

houses of the

wealthy there are two raised seats at the end of the reception-room,

with a

table between them. The seat on the left side is considered the seat of

honour,

and the visitor is invariably pressed into it. Scenes which seem most

amusing

to the stranger are always acted on an occasion of this kind. The host

begs his

visitor to take the most honourable post, while the latter protests

that he is

unworthy of such distinction, and in his turn presses it upon the owner

of the

mansion. And so they may be seen standing in this way for several

minutes

before the matter is settled. It is the same way when a man gives a

dinner; and

if the guests are numerous, it is quite a serious affair to get them

all

seated. In this case it is not only the host and his household who are

begging

the guests to occupy the most honourable seats, but the guests

themselves are

also pressing these favoured places upon each other. Hence the bowing,

talking,

sitting down, and getting up again, before the party can be finally

seated, is

quite unlike anything one sees in other parts of the world, and to the

stranger

is exceedingly amusing, particularly if he does not happen to be hungry. After duly expressing my unfitness to

occupy the

left-hand seat, and attempting to take the other, I was at last forced

into the

seat of honour, the mandarin himself taking the right-hand one. As soon

as we

were seated a servant came in with several cups of tea upon a round

wooden

tray, which cups he placed upon the table between us. Another servant

presented

himself, bringing a handsome brass pipe with a long bamboo stem, which

he

presented to his master. My host handed it immediately over to me, and

begged I

would use it, assuring me at the same time that the tobacco was the

best which

could be had in Ningpo. I declined the invitation, but took a cigar out

of my

pocket, and returned the compliment which he had just paid me. He

informed me

he had once tried a cigar, but that it was too strong for him; so we

compromised matters by each smoking what he had been accustomed to he

his

long bamboo pipe, and I my cigar. As we sat and sipped our tea a

delicious

kind of Hyson Pekoe he asked me many questions concerning my country

and its

productions. Our steamers and ships of war he had seen at Ningpo, and

he owned

they had pleased him greatly. "To be able to go against wind and tide

was

certainly very wonderful." But when I told him that by means of

balloons

we could rise from the earth, and sail through the air, he looked

rather

incredulous, and with a smile on his countenance asked me whether any

of us had

been to the moon. While this conversation was going on, a

large crowd

had assembled in the court, and many of them were pressing into the

reception-hall, in which we were seated. The numerous servants and

retainers of

the mandarin were also inside, and even sometimes took a share in the

conversation which was going on; nor did this seem to give any offence

to their

superior. On one side of the room there was a glass

window

having a gauze or crape curtain behind it, and apparently constructed

to give

light to a passage leading to some of the other parts of the mansion.

While

sitting with my host I had more than once observed the curtain move and

expose

a group of fair faces having a sly peep at me through the window. These

were

his wives and daughters, whom etiquette did not permit to appear in

public or

in the presence of a stranger. I did not appear to notice them

although I saw

them distinctly enough all the time for had I done so they would have

disappeared immediately; and as one rarely has an opportunity of seeing

the

ladies of the higher classes in China, I was willing to look upon their

pretty

faces as long as possible. A circumstance occurred, however, which put

a speedy

end to their peep-show, and for which they had no one but themselves to

blame.

Whether they had fallen out amongst themselves about places at the

window, or

whether it was only a harmless giggle, I cannot tell it sounded very

like the

latter; but the noise, whatever it was, caught the ear of their lord

and

master, who turned his head quickly to the window in question, and

darted a

look of anger and annoyance at the unfortunates, who instantly took to

their

heels, and I saw them again no more. The ladies in this part of China are famed

for their

beauty. It is a curious and striking fact that in this old city and its

vicinity one rarely sees an unpleasing countenance. And this holds good

with the

lower classes as well as it does with the higher. In many other parts

of China

women get excessively ugly when they get old, but even this is not the

case at

Tse-kee. With features of more European cast than Asiatic, and very

pleasing,

with a smooth fair skin, and with a slight colour in their cheeks, just

sufficient to indicate good health, they are almost perfect, were it

not for

that barbarous custom of compressing the feet. Perhaps I ought to add,

that,

from the want of education and this applies to females generally in

China

there is a want of an intellectual expression in the countenance which

renders

it, in my opinion, less beautiful than it would otherwise be. I had now been chatting with my

acquaintance for more

than half an hour, and thought it time to take my leave. But when I

rose for

this purpose he informed me he had prepared luncheon for me in another

room,

and begged I would honour him by partaking of it before I went away. I

tried to

excuse myself, but he almost used force in order to induce me to

remain. He now

led me into a nicely furnished room, according to Chinese ideas, that

is, its

walls were hung with pictures of flowers, birds, and scenes of Chinese

life. It

would not do to criticise these works of art according to our ideas,

but

nevertheless some of them were very interesting. I observed a series of

pictures which told a long tale as distinctly as if it had been written

in

Roman characters. The actors were all on the boards, and one followed

them

readily from the commencement of the piece until the fall of the

curtain.

Numbers of solid straight-backed chairs were placed round the room, and

a large

massive table occupied its centre. This table was completely covered

with

numerous small dishes, containing the fruits of the season and all

sorts of

cakes and sweetmeats, for which the large towns in this province are

famed. In

addition to these there were walnuts from the northern province of

Shantung,

and dried Leechees, Longans, &c., from Fokien and Canton. Then

there were many

kinds of preserves, such as ginger, citron, bamboo, and others, all of

which

were most excellent. A number of small wine-cups, made of the purest

china,

were placed at intervals round the table. Several of the old gentleman's friends had

now joined

us, and we took our places round the table with the usual ceremony,

each one

pressing the most honourable place upon his neighbour. The day was

excessively

warm, and I felt very little inclination to eat, but I was pressed to

do so on

all sides. "Eat cakes," said one; "Eat walnuts," said

another; "Drink wine," said a third; and so on they went, asking me

to partake of every dish upon the table. It was useless to refuse, for

they

seized hold of the different viands and heaped them on my plate and on

the

table at its side. Various kinds of Chinese wines, hot and cold, were

also

pressed upon me, some of which were palatable, but scarcely suited to

the

English taste. I took a little of each in order to please my

entertainer, and

then confined myself to tea, which was also set before us.

I had now prolonged my visit much beyond

the time I

had set apart for it, and quite as long as politeness demanded. But

time spent

in this manner was not altogether unprofitable, inasmuch as one gets an

insight

into Chinese life and manners which we cannot acquire in the streets or

on the

hill-side. My kind host and his friends accompanied me to the outer

door of the

mansion, and, with the palms of our hands laid flat together and held

up before

us, we bowed low several times, muttered our thanks, and bade each

other

farewell. 1 The

British Museum. |