| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XII. Return to Chekiang A journey

to the interior Chinese

country fair Small feet of women How formed, and the results

Stalls at

the fair Ancient porcelain seal same as found in the bogs of Ireland

Theatricals Chinese actors Natural productions of the country

Liliaceous

medicinal plant "Cold water temple" Start for Tsan-tsin

Mountain scenery and productions Astonishment of the people A

little boy's

opinion of my habits.

ON arriving at Shanghae I lost no time in

returning

again to the tea-districts in the interior of the Chekiang province, in

order

to make again arrangements for further supplies of seeds and plants for

the

following autumn. I shall not enter into a description of this part of

my

duties, as it would be nearly a repetition of some of the earlier pages

in this

work. But during the summer and autumn I had many opportunities of

visiting

districts in the interior of the country hitherto undescribed, and to

these

"fresh fields and pastures new," I shall now conduct the reader. The eastern parts of the province, in

which the

islands of the Chusan archipelago and the great cities of Hangchow and

Ningpo

are included, is now pretty well known, partly through my own

researches, and

partly through those of other travellers. The central and western parts

of this

fine province, however, have scarcely as yet been explored by

foreigners, and

therefore a short account of its inhabitants and productions, as

observed by me

during a visit this year, may prove of some interest. Having engaged a

small

boat at Ningpo to take me up to one of the sources of the river, which

flows

past the walls of that city, I left late one evening with the first of

the

flood-tide. We sailed on until daylight next morning, when the ebb made

strong

against us, and obliged us to make our boat fast to the river's bank,

and wait

for the next flood. The country through which we had passed during the

night

was perfectly flat, and was one vast rice-field, with clumps of trees

and

villages scattered over it in all directions. Like all other parts of

China,

where the country is flat and fertile, this portion seemed to be

densely

populated. We were now no great distance from the hills which bound the

south-west side of this extensive plain, a plain some thirty miles

from east

to west, and twenty from north to south. Part of the toad was the same

I had

travelled the year before on my way to the Snowy Valley.

When the tide turned to run up we again

got under

way, and proceeded on our journey. In the afternoon we reached the

hills; and

as our little boat followed the winding course of the stream, the wide

and

fertile plain through which we had passed was shut out from our view.

About

four o'clock in the afternoon we reached the town of Ning-Kang-jou,

beyond

which the river is not navigable for boats of any size; and here I

determined

to leave my boat, and make excursions into the surrounding country. It

so

happened that I arrived on the eve of a fair, to be held next day in

the little

town in which I had taken up my quarters. As I walked through the

streets in

the evening of my arrival great preparations were evidently making for

the

business and gaieties of the following day. The shop-fronts were all

decorated

with lanterns; hawkers were arriving from all parts of the surrounding

country,

loaded with wares to tempt the holiday folks; and as two grand

theatrical

representations were to be given, one at each end of the town, on the

banks of

the little stream, workmen were busily employed in fitting up the

stages and

galleries, the latter being intended for the accommodation of those

who gave

the play and their friends. Everything was going on in the most

good-humoured

way, and the people seemed delighted to see a foreigner amongst them,

and were

all perfectly civil and kind. I had many invitations to come and see

the play

next night; and the general impression seemed to be, that I had visited

the

place with the sole intention of seeing the fair. Retiring early to rest, I was up next

morning some

time before the sun, and took my way into the country to the westward.

Even at

that early hour 4 A.M. the country-roads were lined with people

pouring

into the town. There were long trains of coolies, loaded with fruits

and

vegetables; there were hawkers, with their cakes and sweetmeats to

tempt the

young; while now and then passed a thrifty housewife, carrying a web of

cotton

cloth, which had been woven at home, and was now to be sold at the

fair. More

gaily dressed than any of these were small parties of ladies limping

along on

their small feet, each one having a long staff in her hand to steady

her, and

to help her along the mountain-road. Behind each of these parties come

an

attendant coolie, carrying a basket of provisions, and any other little

article

which was required during the journey. On politely inquiring of the

several

parties of ladies where they were going to, they invariably replied in

the

language of the district "Ta-pa-Busa-la," we are going to worship

Buddha. Some of the younger ones, particularly the good-looking,

pretended to

be vastly frightened as I passed them on the narrow road; but that this

was

only pretence was .clearly proved by the joyous ringing laugh which

reached my

ears after they had passed and before they were out of sight. It is certainly a most barbarous custom

that of

deforming the feet of Chinese ladies, and detracts greatly from their

beauty.

Many persons think that the custom prevails only amongst persons of

rank or

wealth, but this is a great mistake. In the central and eastern

provinces of

the empire it is almost universal, the fine ladies who ride in

sedan-chairs,

and the poorer classes who toil from morning till evening in the

fields, are

all deformed in the same manner. In the more southern provinces, such

as Fokien

and Canton, the custom is not so universal; boat-women and

field-labourers

generally allow their feet to grow to the natural size. Here is one of

a

peculiar class of countrywomen, to be met with near Foo-chow, from the

talented

pencil of Mr. Scarth.  Foo-chow Countrywoman. Dr. Lockhart, whose name I have already

mentioned in

these pages, gives the following as the results of his extensive and

varied

experience on this subject. He says: "Considering the vast number of females

who have

the feet bound up in early life, and whose feet are then distorted, the

amount

of actual disease of the bones is small; the ancle is generally tender,

and

much walking soon causes the foot to swell, and be very painful, and

this

chiefly when the feet have been carelessly bound in infancy. To produce

the

diminution of the foot, the tarsus or instep is bent on itself, the os

calcis

or heel-bone thrown out of the horizontal position, and what ought to

be the

posterior surface, brought to the ground; so that the ancle is, as it

were,

forced higher up than it ought to be, producing in fact artificial

Talipes

Caleaneus; then the four smaller toes are pressed down under the

instep, and

checked in their growth, till at adult age all that has to go into the

shoe is

the end of the os calcis and the whole of the great toe. In a healthy

constitution this constriction of the foot may be carried on without

any very

serious consequences; but in scrofulous constitutions the navicular

bone, and

the cuneiform bone supporting the great toe, are very liable, from the

constant

pressure and irritation to which they are exposed, to become diseased;

and many

cases have been seen where caries, softening, and even death of the

bone have

taken place, accompanied with much suppuration and great consequent

suffering.

Chinese women have naturally very small hands and feet, but this

practice of

binding the feet utterly destroys all symmetry according to European

ideas, and

the limping uncertain gait of the women is, to a foreigner, distressing

to see.

Few of the Chinese women can walk far, and they always appear to feel

pain when

they try to walk quickly, or on uneven ground. "The most serious inconvenience to which

women

with small feet are exposed," he observes, "is that they so

frequently fall and injure themselves. During the past year, several

cases of

this kind have presented themselves. Among them was one of an old

woman,

seventy years of age, who was coming down a pair of stairs and fell,

breaking

both her legs; she was in a very dangerous state for some time, on

account of

threatened mortification of one leg, but the unfavourable symptoms

passed off,

and finally the bones of both legs united, and she is able to walk

again. "Another case was also that of an elderly

woman,

who was superintending the spring cutting of bamboo shoots in her

field, when

she fell over some bamboos, owing to her crippled feet slipping among

the

roots; a compound fracture of one leg was the consequence, and the

upper

fragment of the bone stuck in the ground; the soft parts of the leg

were so

much injured, that amputation was recommended, but her friends would

not hear

of it, and she soon afterwards died from mortification of the limb. "The third case was that of a woman, who

also

fell down stairs and had compound fracture of the leg; this case is

still under

treatment, and is likely to do well, as there was not very much injury

done to

the soft parts in the first instance." About eight o'clock I returned to the

town, and took

the principal temple on my way. The sight which presented itself here

was a

curious and striking one. Near the doors were numerous venders of

candles and

joss-stick, who were eagerly pressing the devotees to buy; so eager

were they,

indeed, that I observed them in several instances actually lay hold of

the

people as they passed; and strange to say, this rather rough mode of

getting

customers was frequently successful. Crowds of people were going in and

coming

out of the temple exactly like bees in a hive on a fine summer's day.

Some

halted a few moments to buy their candles and incense from the dealers

already

noticed; while others seemed to prefer purchasing from the priests in

the

temple. Nor were the venders confined to those who sold things used

only in the

worship of Buddha. Some had stalls of cakes and sweetmeats; others had

warm and

cold tea, snuff-bottles, fans, and a hundred other fancy articles which

it is

needless to enumerate. Doctors were there who could cure all diseases;

and

fortunetellers, too, seemed to have a full share of patronage from a

liberal

and enlightened public. In front of the altar other scenes were being

acted.

Here the devotees by far the largest portion being females were

prostrating

themselves many times before the Gods; and each one, as she arose from

her

knees, hastened to light some candles and incense, and place these upon

the

altar, then returning to the front, the prostrations were again

repeated, and

then the place was given up to another, who repeated the same solemn

farce. And

so they went on during the whole of that day, on which many thousands

of

people must have paid their vows at these heathen altars.

I may here mention, in passing, that I

picked up two

articles at this place, of considerable interest to antiquaries in

Europe. One

was a small porcelain bottle, exactly similar in size, form and

colouring to

those found in ancient Egyptian tombs. The characters on one side are

also

identical, and are a quotation from one of the Chinese poets "Only

in

the midst of this mountain." I have already alluded to these bottles in

one of the

earlier chapters, and need say nothing further about them here. They

are to be

met with not unfrequently in doctors' shops and old stalls; several

persons,

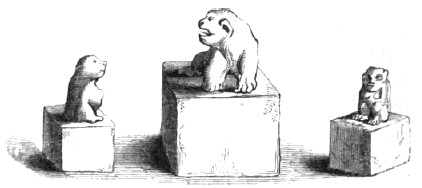

both in China and England, possess specimens. The other article I have mentioned is far

more

curious and interesting. It is a small porcelain seal identical with

those

found of late years in the bogs of Ireland. On the 6th of May, 1850,

Mr. Letty

read a very curious and interesting paper on this subject before the

Belfast

Literary Society, and he has since published it with drawings and

descriptions

of the different seals. One was found when ploughing a field in

Tipperary,

another in the county of Down, a third in the bed of the river Boyne,

and a

fourth near Dublin. That these seals have lain in the bogs and rivers

of

Ireland for many ages there cannot be the slightest doubt. The peculiar

white

or rather cream-coloured porcelain of which they are composed, has not

been

made in China for several hundred years. The Chinese, who laugh at the

idea of

the bottles being considered ancient which have been found in the tombs

of

Egypt, all agree in stating that these seals are from one thousand to

two thousand

years old. They are very rare in China at the present

day. I had

the greatest difficulty in getting the few which are now in my

possession,

although my opportunities of picking up such things were greater than

those of

most persons in China. It is therefore absurd to suppose that those

found in

Ireland can have been brought over of late years by sailors, or

captains of

ships, or even by either of the two embassies to Peking. Here is a

sketch of

some of those found in China at the present day. Those who are

fortunate enough

to possess the Irish ones will see an exact resemblance to their own.  Ancient

Porcelain Seals. There is therefore no doubt that those

rare and

ancient seals found in China at the present day are identical with

those found

in Ireland. That the latter must have been brought over at a very early

period,

and that they must have lain for many ages in the bogs and rivers of

that

island seems also quite certain. But when they came there, how they

came, and

what were the circumstances connected with their introduction, are

questions

which we cannot answer. To do this satisfactorily we should probably

have to

consult a book of history, written, studied, and lost long before that

of the

present history of Ireland. The streets of the town were now crowded

with people;

and the whole scene reminded me of a fair in a country-town in England.

In

addition to the usual articles in the shops, and an unusual supply of

fruits

and vegetables, there was a large assortment of other things which

seemed to be

exposed in quantity only on a fair-day. Native cotton cloths, woven by

handlooms in the country, were abundant, mats made from a species of

Juncus,

and generally used for sleeping upon, clothes of all kinds, both new

and

second-hand, porcelain and wooden vessels of various sorts, toys,

cakes,

sweetmeats, and all the common accompaniments of an English fair.

Various

textile fibres of interest were abundant, being produced in large

quantities in

the district. Amongst these, and the chief, were the following: hemp,

jute,

China grass (so called) being the bark of Urtica nivea and

the

Juncus already noticed. A great number of the wooden vessels were made

of the

wood of Cryptomania japonica, which is remarkable for the

number of

beautiful rings and veins which show to great advantage when the wood

is

polished. In the afternoon the play began, and attracted its thousands of happy spectators. As already stated, the subscribers, or those who gave the play, had a raised platform, placed about twenty yards from the front of the stage, for themselves and their friends. The public occupied the ground on the front and sides of the stage, and to them the whole was free as their mountain-air, each man, however poor, had as good right to be there as his neighbour. And it is the same all over China :the actors are paid by the rich, and the poor are not excluded from participating in the enjoyments of the stage. The Chinese have a curious fancy for

erecting these

temporary theatres on the dry beds of streams. In travelling through

the

country I have frequently seen them in such places. Sometimes; when the

thing

is done in grand style, a little tinsel town is erected at the same

time, with

its palaces, pagodas, gardens, and dwarf plants. These places rise and

disappear as if by the magic of the enchanter's wand, but they serve

the

purposes for which they are designed, and contribute largely to the

enjoyment

and happiness of the mass of the people. On the present occasion I did not fail to

accept the

invitations which had been given me in the earlier part of the day. As

I did

not intend to remain for a great length of time I was content to take

my place

in the "pit," which I have already said is free to the public. But

the parties who had given the play were too polite to permit me to

remain

amongst the crowd. One of them a respectable-looking man, dressed

very gaily

came down and invited me to accompany him to the boxes. He led me up

a narrow

staircase and into a little room in which I found several of his

friends

amusing themselves by smoking, sipping tea, and eating seeds and fruits

of

various kinds. All made way for the stranger, and endeavoured to place

me in

the best position for getting a view of the stage. What a mass of human

beings

were below me! The place seemed full of heads, and one might suppose

that the

bodies were below, but it was impossible to see them, so densely were

they

packed together. Had it not been for the stage in the background with

its

actors dressed in the gay-coloured costumes of a former age, and the

rude and

noisy band, it would have reminded me more of the hustings at a

contested

election in England than anything else. But taken as a whole, there was

nothing

to which I could liken it out of China. The actors had no stage-scenery to assist

them in

making an impression on the audience. This is not the custom in China.

A table,

a few chairs, and a covered platform are all that is required. No

ladies are

allowed to appear as actresses in the country, but the way in which the

sex is

imitated is most admirable, and always deceives any foreigner ignorant

of the

fact I have stated. In the present instance each actor

repeated his part

in a singing falsetto voice. The whole interest of the piece must have

lain in

the story itself, for there was nothing natural in the acting, the sham

sword-fights perhaps excepted. One or two of these occurred in the

piece during

the time I was a spectator, and they were certainly natural enough,

thoroughly

Chinese and very amusing. An actor rushed upon the stage amid the

clashing of

timbre's, beating of gongs, and squeaking of other instruments. He was

brandishing a short sword in each hand, now and then wheeling round

apparently

to protect himself in the rear, and all the time performing the most

extraordinary

actions with his feet, which seemed as if they had to do as much of the

fighting as the hands. People who have seen much of the manoeuvring of

Chinese

troops will not call this unnatural acting. But whatever a foreigner

might

think of such "artistes," judging from the intense interest and

boisterous mirth of a numerous audience, they performed their parts to

the

entire satisfaction of their patrons and the public.

"How-pa-bow," said my kind friends, as I

rose to take my leave; "is it good or bad?" Of course I expressed my

entire approbation, and thanked them for the excellent view I had

enjoyed of

the performance through their politeness. It was now night dark the

lanterns were lighted, the crowd still continued, and the play went on.

Long after

I left them, and even when I retired for the night, I could hear, every

now and

then, borne on the air the sounds of their rude music, and the shouts

of

applause from a good-humoured multitude. The natural productions of this part of

China now

claim a share of our attention. Much of the level land among the hills

in this

part of the country, being considerably higher than the great Ningpo

plain, is

adapted to the growth of other crops than rice. The soil in these

valleys is a

light rich loam, and is in a state of high cultivation; indeed, I never

witnessed fields so much like gardens as these are. The staple summer

crops are

those which yield textile fibres, such as those I saw in the fair

already

described. A plant well known by the name of jute in India a species

of

Corchorus which has been largely exported to Europe of late years

from India,

is grown here to a very large extent. In China this fibre is used in

the

manufacture of sacks and bags for holding rice and other grains. A

gigantic

species of hemp (Cannabis) growing from ten to fifteen feet in height,

is also

a staple summer crop. This is chiefly used in making ropes and string

of

various sizes, such articles being in great demand for tracking the

boats up

rivers, and in the canals of the country. Every one has heard of China

grasscloth, that beautiful fabric made in the Canton province, and

largely

exported to Europe and America. The

plant which is supposed to produce this (Urtica nivea) is also

abundantly grown in the western part of this province, and in the

adjoining

province of Kiangse. Fabrics of various degrees of fineness are made

from this

fibre, and sold in these provinces; but I have not seen any so fine as

that

made about Canton. It is also spun into thread for sewing purposes, and

is

found to be very strong and durable. There are two very distinct

varieties of

this plant common in Chekiang one the cultivated, the other the wild.

The

cultivated variety has larger leaves than the other; on the upper side

they are

of a lighter green, and on the under they are much more downy. The

stems also

are lighter in colour, and the whole plant has a silky feel about it

which the

wild one wants. The wild variety grows plentifully on sloping banks, on

city

walls, and other old and ruinous buildings. It is not prized by the

natives,

who say its fibre is not so fine, and more broken and confused in its

structure

than the other kind. The cultivated kind yields three crops a year. The last great crop which I observed was

that of a

species of juncus, the stems of which are woven into beautiful mats,

used by

the natives for sleeping upon, for covering the floors of rooms, and

for many

other useful purposes. This is cultivated in water, somewhat like the

rice-plant, and is therefore always planted in the lowest parts of

these

valleys. At the time of my visit, in the beginning of July, the harvest

of this

crop had just commenced, and hundreds of the natives were busily

employed in

drying it. The river's banks, uncultivated land, the dry gravelly bed

of the

river, and every other available spot was taken up with this operation.

At grey

dawn of morning the sheaves or bundles were taken out of temporary

sheds,

erected for the purpose of keeping off the rain and dew, and shaken

thinly over

the surface of the ground. In the afternoon, before the sun had sunk

very low

in the horizon, it was gathered up again into sheaves and placed under

cover

for the night. A watch was then set in each of the sheds; for however

quiet and

harmless the people in these parts are, there is no lack of thieves,

who are

very honest if they have no opportunity to steal. And so the process of

winnowing went on day by day until the whole of the moisture was dried

out of

the reeds. They were then bound up firmly in round bundles, and either

sold in

the markets of the country, or taken to Ningpo and other towns where

the

manufacture of mats is carried on, on a large scale.

The winter crops of this part of China

consist of

wheat, barley, the cabbage oil-plant, and many other kinds of

vegetables on a

smaller scale. Large tracts of land are planted with the bulbs of a

liliaceous

plant probably a Fritillaria which are used in medicine.

This is

planted in November, and dug up again in April and May. In March these

lily-fields are in full blossom, and give quite a feature to the

country. The

flowers are of a dingy greyish white, and not very ornamental. It seems to me to be very remarkable that

a country

like China, rich in textile fibre, oils of many kinds, vegetable

tallow,

dyes, and no doubt many other articles which have not come under my

notice

should afford so few articles for exportation. I have no doubt that as

the

country gets better known, our merchants will find many things besides

silk and

tea, which have hitherto formed almost the only articles exported in

quantity

to Europe and America. When I was travelling in the part of the

country I

have been describing, the weather was extremely hot, July and August

being

the hottest months of the year in China. When complaining of the

excessive heat

to some of my visitors, I was recommended to go to a place called by

them the Lang-shuy-ain,

or "cold water temple," situated in the vicinity of the town in which

I was staying. In this place they told me both air and water were cold

notwithstanding

the excessive heat of the weather. On visiting the place I found it an

old,

dilapidated building, which had evidently seen more prosperous days.

Ascending

a few stone steps, I reached the lower part of the edifice, when I felt

at once

a sudden change in the temperature, something like that which one

experiences

on going into an ice-house on a hot summer's day. My guide led me to

the

further corner of this place, and pointed to some stone steps which

seemed to

lead down to a cave or some such subterranean place, and desired me to

walk

down. As it appeared perfectly dark to me on coming from the bright

sunshine, I

hesitated to proceed without a candle. On this being brought, I was

much

disappointed in finding the steps were only a few in number and led to

nowhere.

It appeared that in the more prosperous days of the temple there had

been a

well of clear water at the bottom of the steps, but now that was choked

up with

stones and rubbish. I was able, however, to procure a little water

nearly as cold

as if it had been iced. The stones in this part of the building were

also very

cold to the touch, and a strong current of cold air was coming out of

the earth

at this particular point. I regretted much not having my thermometer

with me to

have tested the difference of the temperature with accuracy. On the

floor of

the temple a motley group of persons was presented to my view. Beggars,

sick

persons, and others who had taken refuge from the heat of the sun were

lolling

about, evidently enjoying the cool air which filled the place. It

appeared to

be free to all, rich and poor alike. There are some large clay-slate

and

granite quarries near this place; and I afterwards found several

springs of

water issuing from the clay-slate rocks quite as cold as that in the

"cold

water temple." Having spent several days in the town of

Ningkang-jou, I determined to proceed onwards to a large temple

situated

amongst the hills to the westward, and distant, as I was informed, some

twenty

or thirty le. Packing up my bed and a few necessaries, I started in a

mountain

chair one morning, after an early breakfast. Leaving the town behind

me, the

road led me winding along the side of a hill, following the course of

the

little stream. The scenery here was perfectly enchanting. The road,

though

narrow, like all Chinese roads, was nicely paved and oftentimes shaded

by the

branches of lofty trees. Above me rose a sloping hill, covered with

trees and

brushwood, while a few feet below me was seen the little stream

trickling over

its gravelly bed and glistening in the morning sun. Now and then I

passed a

pool where the water was still and deep, but generally the river, which

is

navigable for large ships at Ningpo, was here not more than ankle deep.

Shallow

as it was, however, the Chinese were still using it for floating down

the

productions of these western. hills. Small rafts made of bamboo, tiny

flat-bottomed boats, and many other contrivances were employed to

accomplish

the end in view. When the river was so shallow that the boatman could

not use

his scull, he might oftentimes be seen walking in the river and

dragging his

boat or raft over the stones into deeper water. As I passed along, I

observed

several anglers busily employed with rod and line real Izaak Waltons

it

seemed and although they did not appear very expert, and their tackle

was

rather clumsy, yet they generally succeeded in getting their baskets

well

filled. Altogether, this scene, which I can only attempt to describe,

was a

charming one, a view of Chinese country-life, telling plainly that

the

Chinese, however strange they may sometimes appear, are, after all,

very much

like ourselves. My road at length left the hill-side and

little

stream, and took me across a wide and highly cultivated valley, several

miles

in extent, and surrounded on all sides by hills, except that one

through which

the river winded in its course to the eastward. I passed through two

small

towns in this valley where the whole population seemed to turn out to

look at

me. Everywhere I was treated with the most marked politeness, and even

kindness, by the inhabitants. "Stop a little, sit down, drink tea,"

was said to me by almost every one whose door I passed. Sometimes I

complied

with their wishes; but more generally I simply thanked them, and pushed

onwards

on my journey. In the afternoon I arrived at the further end of the

valley and

at the foot of a mountain pass. As I gradually ascended this winding

path, the

valley through which I had passed was entirely shut out from my view.

Nothing

was now seen but mountains, varying in height and form, some about

2000, and

others little less than 4000 feet above the level of the sea, some

formed of

gentle slopes, with here and there patches of cultivation, others

steep and

barren, where no cultivation can ever be carried on, except that of

brushwood,

which the most barren mountains generally furnish. The Chinese pine and

Japan

cedar were almost the only trees of any size which I observed as I

passed

along. A little higher up I came to fine groves of the bamboo the

famous

maou-chok, already noticed the finest variety of bamboo in China, and

always

found growing in the vicinity of Buddhist temples.

In a small valley amongst these mountains,

some 2000

feet high, the temple of Tsan-tsing was at last seen peeping out from

amongst

the trees. The building in itself is of a much less imposing character

than

others I have seen in this province and in Fokien; but, like all others

of its

kind, it is pleasantly situated in the midst of the most romantic

scenery. In addition

to the pines and bamboos already noticed, were several species of oaks

and

chesnuts, the former producing good-sized timber. But the finest tree

of all,

and quite new to me, was a beautiful species of cedar or larch; which I

observe

Dr. Lindley, to whom I sent specimens, calls Abies Kζmpferi.

When I entered the court of the temple the priests seemed quite lost in astonishment. No other foreigner, it seemed, had been there before, and many of them had only heard of us by name. Some of them stood gazing at me as if I were a being from another world, while others ran out to inform their friends of my arrival. My request for quarters was readily granted; and being now an old traveller, I was soon quite at home amongst my new friends. Late in the afternoon, long trains of coolies men and boys passed the temple from a district further inland, loaded with young bamboo shoots, which are eaten as a vegetable and much esteemed. The news of the arrival of a foreigner at the temple seemed to fly in all directions; and we were crowded during the evening with the natives, all anxious to get a glimpse of me. Some seemed never tired of looking at me; others had a sort of superstitious dread mingled with curiosity. One little urchin, who had been looking on with great reverence for some time, and on whom I flattered myself I had made a favourable impression, undeceived me by putting the following simple question to his father: "If I go near him, will he bite me?" This, I confess, astonished me; for although I had no tail, was not exactly the same colour as they were, and did not wear the same kind of dress, I did not expect to be taken for a wild animal. What strange tales must have been told these simple country people of the barbarians during the last Chinese war? |