| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

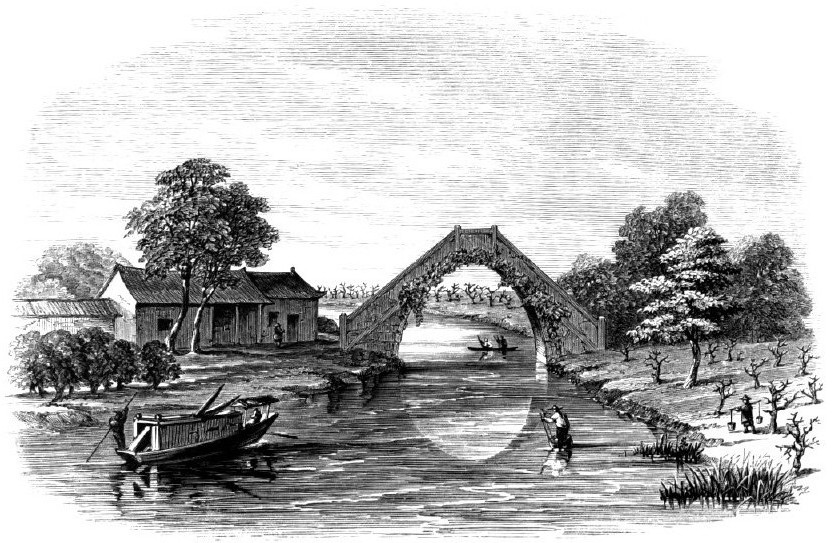

| CHAPTER XVI. Leave Shanghae for

the silk country — Melancholy results of

the Shanghae rebellion — Country and productions about Cading — Indigo

and

safflower — Bamboo paper-making — Insects — Lakes and marshy country —

Visit

the town of Nan-tsin in the silk districts — Its shops and inhabitants

—

Producers of raw silk and silk merchants — Description of silk country

— Soil —

Method of cultivating the mulberry — Valuable varieties — Increased by

grafting

and not by seeds — Method of gathering the leaves — Hills near

Hoo-chow-foo — Temples

and priests.

ON the evening of the eighth of

June I took my

departure from Shanghae, en route for the great silk district for which

the

province is famed all over the world, and for the mountainous country

which

lies to the westward of the plain of the Yang-tse-kiang. As my boat

proceeded

rapidly up the Soochow branch of the river, I soon approached the

ground where

the imperialists had their principal camp during the siege of the city,

and

where so many hundreds of poor wretches were executed after the city

was

evacuated. It was a calm and beautiful evening. The sounds of civil

warfare and

of a camp teeming with barbarous soldiers, which had been so often

heard a few

months before, had now passed away, — the sword had been converted into

the ploughshare

— and the husbandman was quietly engaged in the cultivation of his

fields, now

enriched with the blood and bodies of his countrymen.

As I passed the site of the old

camp I sat on the

outside of my boat smoking my cigar in the cool air of the evening, and

musing

upon the events of the preceding years. The wind at the time blew

softly from

the south, and before it reached the river on which I was sailing it

had to

pass over the site of the old encampment. The first puff that reached

me almost

made me sick, and it has nearly the same effect on me even now when I

think of

it as I write. Although I had seen none of the executions which had

taken place

a short time before, I did not require any one to inform me that this

was the

"field of blood." Here hundreds of headless bodies scarcely covered,

or only with an inch or two of earth, lay in a state of decomposition,

and the

stench from them filled and polluted the air. Here, then, was the end

of the

Shanghae rebellion, which, at one time, was so much lauded and

encouraged by

foreigners at that port. The country was devastated for miles round,

the city

lay in ruins, thousands of the peaceful inhabitants were rendered

homeless and

friendless, and the authors of this state of things, who used to strut

about dressed

in the richest silks and satins (which they plundered from the shops

and houses

of the wealthy), smoke opium, and make a profession of regard for the

Christian

religion, were now either skulking fugitives, or had atoned with their

blood

for their crimes. I was heartily glad when my boat

had passed the place

into purer air. As my boatmen sculled all night, in the morning we were

thirty

miles distant from Shanghae and within sight of the walls of Cading, an

old

city which I passed some years ago, when on my way to Soo-chow-foo.

Here I

remained for several days, inspecting the natural productions of the

country.

As this city and the surrounding country is frequently visited by

missionaries

and other residents in Shanghae, a foreigner is a common sight to the

natives,

who do not crowd round him as they do in more inland towns. I could,

therefore,

pursue my investigations in town and country without being molested in

any way

whatever. The surrounding country,

although a plain, is

somewhat higher and more undulating in its general character than that

about

Shanghae. The land is exceedingly fertile and admirably adapted for

Chinese

cotton cultivation, and consequently we find that cotton is the staple

production of the district. But there are many other articles besides

which are

worthy of notice. The Shanghae indigo (Isates indigotica)

is largely

cultivated in the Ke-wang-meow district, a few miles to the south. The

"Hong-wha," a variety of safflower (Carthamnus tinctorius),

was found for the first time in fields near Cading. This dye, I was

informed,

was held in high esteem by the Chinese, and is used in dyeing the red

and

scarlet silks and crapes which are so common in the country and so much

and

justly admired by foreigners of every nation. Although I had not met

with the

safflower in cultivation in any other part of the country, my servants

informed

me that large quantities were annually produced in the Chekiang

province near

Ningpo. At this season (June 10th) the crop of flowers had been

gathered, and all

the plants removed from the land, except some few here and there on the

different farms which had been left for seed. The seed was not yet

ripe, so

that I could not get a supply, but I determined to return that way and

secure a

portion to send to the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India,

in

order to compare the Chinese with the Indian safflower. I believe they

have

turned out to be alike, or nearly so. Large quantities of fruit and

vegetables

are also produced in the vicinity of the city. I observed orchards of

apple-trees, which is rather a rare sight in this district. The variety

of

apple was a small one, about as big as our golden pippin, but excellent

in

flavour; indeed, the only kind worth eating in this part of China.

Melons of

several different kinds were also extensively cultivated: when they are

ripe

the markets are literally crowded to overflowing with them, and they

are eaten

by the natives much in the same way as apples are with us; in fact they

seem to

be, so to speak, the apples of the country. In the canals near the city

there were large

quantities of bamboos partially covered with mud, so as to be pressed

under

water. These, I believe, were intended to be made into paper after they

had

been soaked for some time. The whole of the process of making paper

from the

bamboo did not come under my notice while travelling in the country,

but I

believe it is carried out somewhat in the following manner: — After

being

soaked for some time in the way I have noticed, the bamboos are split

up and

saturated with lime and water until they become quite soft. They are

then

beaten up into a pulp in mortars, or where waterpower is at hand, as in

the

hilly districts, the beating or stamping process is done by means of

stampers,

which rise and fall as the cogs which are placed on the axis of the

water-wheel

revolve. When the mass has been reduced to a fine pulpy substance it is

then

taken to a furnace and well boiled until it has become perfectly fine,

and of

the proper consistency. It is then formed into sheets of paper. Bamboo-paper is made of various

degrees of fineness

according to the purposes for which it is intended. It is not only used

for

writing upon, and for packing with, but a large quantity of a coarse

description is made for the sole purpose of mixing with the mortar used

by

bricklayers. In the fields about Cading I

found two fine species

of carabus, under stones, which were highly prized by entomologists at

home. On

the first discovery of these insects I showed them to a group of

children who

were with me, and offered to

buy all

they brought me at the rate of thirty cash for each perfect specimen. I

dare

say they considered me insane or foolish, and I thought I could detect

a look

of pity on some countenances; but the motley group by which I was

surrounded

was soon scattered in all directions, engaged in turning over stones,

lumps of

loose earth and rubbish, and eagerly looking for the insects I wanted.

The news

was soon communicated to the old women in the villages, who were as

anxious as

the children, and many were the disputes and tumbles they had when

scrambling

for these beetles. By this means I soon procured as

many specimens of

these insects as I required, and then the difficulty was to induce my

crowds of

collectors to leave off collecting. I have already stated that the

natives

always believed I was collecting insects for medicine, and, therefore,

had no

idea of some forty or fifty of each kind being enough.

Leaving Cading I pursued my

journey to the westward

in the direction of Tsing-poo. Soon after dark I found myself on the

borders of

an extensive sheet of water. My boatmen refused to proceed farther that

night,

telling me they could not find their way in the dark, and that if the

wind rose

we would be placed in a dangerous position. As this part of the country

was

unknown to me I considered it best to allow the men to have their own

way, and

so we brought up for the night. When I awoke at daybreak on the

following morning we

were already under way, and sailing with a fair wind across the lake.

It was

not difficult to perceive the justice of the remarks made by the

boatmen the

evening before; indeed, it seemed a difficult matter to find our way in

broad

daylight. This is a most extraordinary part of the country: the lake,

or rather

lakes, extend in all directions for many miles, sometimes so narrow as

to have

the appearance of canals, and then again expanding into large sheets of

water.

Everywhere the shores are low, and have a most irregular outline formed

by a

succession of reed-covered capes and deep bays. After sailing for a distance of

six or eight miles we

came to what appeared at first sight to be a canal leading out of the

lake. It

proved, however, to be merely a neck of water which led into another

lake equal

in size to that which we had just crossed. And so we went on during the

whole

day through this dreary region. The low marshy shores seemed to be

thinly

inhabited, although in the neighbourhood of the richest and most

populous part

of the Chinese empire; indeed, almost the only sign of the place being

inhabited by human beings was, strange to say, the numerous coffins and

graves

of the dead, which were continually coming into view as we sailed

along. It is

not improbable, however, that many of these had been brought from other

districts to those lucky spots and laid down, or

interred according

to circumstances, by the surviving

relatives. The lakes themselves had a much

more lively

appearance than those dreary shores. The white and brown sails of boats

like

our own were observed in great numbers making for the mouths of the

various

canals which form the highways to the large towns and cities in this

part of

China. Those seen going in a southerly direction were bound for

Hang-chow-foo,

and the towns in that district; those sailing northwards were on their

way to

Soo-chow-foo, while those going in the same direction as ourselves were

for the

silk country and its rich and populous cities. The water of the lakes was as

smooth as glass, and in

many places very shallow. Various species of water-plants, such as Trapa

bicornus, Nympheas, &c., were common, while here and

there I came upon

the broad prickly leaves of Euryale ferox covering

the surface of the

water. In the afternoon the scenery

began to assume an

appearance somewhat different from that of the morning. The country was

evidently getting higher in level and more fertile and populous. To the

westward I thought I could detect a real boundary to the waters, but I

did not

feel quite certain of this as I had been deceived several times during

the day.

About five P.M. we arrived at a place named Ping-wang or Bing-bong, as

it is

pronounced in the dialect of the district. This proved to be a small

bustling

town on the edge of the lakes, and rather important from the central

position

which it occupies. Fine navigable canals lead from it to all the

important

towns of this large and fertile plain. A very fine one leads on to the

city of

Hoo-chow to which I was bound. On one side it has a substantial paved

pathway,

which is a high road to foot-passengers, and is also used by the

boat-people in

tracking their boats and junks. I was now able to leave my boat to be

sculled

slowly along, and walk along the banks of the canal.

I had reached the eastern borders of the great silk country of China — a country which in the season of 1853-54 exported upwards of 58,000 bales of raw silk.

The mulberry was now observed on

the banks of the

canal, and in patches over all this part of the country. The lakes

which I had

passed through, and which I have endeavoured to describe, were now left

behind,

and a broad and beautiful canal stretched far away to the westward, and

led to

the great silk-towns of Nan-thin and Hoo-chow-foo. Hitherto the country

had

been completely flat, but now some hills at a great distance on my

right-hand

came into view. These I afterwards ascertained were the

Tung-t'ing-shans,

situated on the T'ai-hu Lake — one of the largest lakes in China, which

covers

a considerable extent of country between the cities of Hang-chow-foo

and

Soochow-foo. As we passed along the country seemed exceedingly rich and

fertile; and mulberry-plantations met the eye in every direction. A.

great

quantity of rice was also produced on the lower lands. The natives

seemed well

to do in the world, having plenty of work without oppression, and

enough to

procure the necessaries and simple luxuries of life. It was pleasant to

hear

their joyous and contented songs as they laboured amongst the

mulberry-plantations and rice-fields. In the evening we arrived at

Nan-tsin, and as I was

anxious to see something of this celebrated silk-town by daylight, I

determined

on remaining there for a few days. Early next morning I was up and on

my way to

see the town. Even at this early hour — five A.M. — the roads were full

of

people; for like other nations the Chinese hold their markets in the

morning.

The streets in the town were lined with vegetables of all kinds, and

the fruits

of the season were abundant and cheap, particularly water-melons,

peaches,

plums, &c. Butchers' stalls groaned under loads of fat pork;

there was an

abundance of fresh and salt fish; ducks, geese, and fowls, were there

in

hundreds, and, indeed, everything was there which could tempt the eye

of the

Chinese epicure, except cats, rats, and young puppies, and these are

not

appreciated in this part of the country. Frogs are in great demand in all

the Chinese towns,

both in the north and south, wherever I have been, and they were very

abundant

in Nantsin. They abound in shallow lakes and rice fields, and many of

them are

very beautifully coloured, and look as if they had been painted by the

hand of

a first-rate artist. The vendors of these animals skin them in the

streets in

the most unmerciful and apparently cruel way which I have already

described. There are many good streets and

valuable shops in

Nan-tsin, but they are very much like what I have seen and described in

other

cities in China. What struck me most was the large quantity of raw silk

which

was here exposed for sale. Soon after daylight the country people began

to

arrive with their little packets of silk, which they intended to sell

to the

merchants. The shops for the purchase of this article appeared to be

very

numerous in all the principal streets. Behind the counter of each shop

stood

six, eight, and sometimes more, clean, respectable-looking men, who

were silk

inspectors, and whose duty was to examine the quality of the silk

offered for

sale, and to name its value. It was amusing to notice the quietness of

these

men compared with the clamorous crowds who stood in front of their

shops with

silk for sale. Each one was expatiating on the superior quality of his

goods

and the lowness of the offer that had been made to him. Many of the

vendors

were women, and in all instances they were the most noisy. The shopmen

took

everything very quietly, and rarely offered a higher price than they

had done

in the first instance. But notwithstanding all the noise and bustle

everything seemed

to go on satisfactorily, and when the money was paid the people went

off in

high spirits, apparently well satisfied with the sales they had

effected. From the observations which I

made at this time on

the farms and markets in this the great silk country of China, it

appears that,

however large in the aggregate the production of silk may be in the

country,

this quantity is produced not by large farmers or extensive

manufactures, but

by millions of cottagers, each of whom own and cultivate a few roods or

acres

of land only. Like bees in a hive each contributes his portion to swell

the

general store. And so it is with almost every production in the

celestial

empire. Our favourite beverage, tea, is produced just in the same way.

When the

silk has thus been bought in small samples from the original producers,

it is

then the business of the native inspectors and merchants to sort it and

arrange

it into bales of similar quality for home consumption or for

exportation. Nan-tsin is not a walled city,

and politically it is

a place of small importance. But it is a place of great wealth and

size,

extending for miles on each side of the canal, and far back into the

country. I

believe there is a larger trade in silk done here than even in the city

of

Hoo-chow-foo itself. The people generally seemed to have plenty of

work, and

judging from their clean, healthy, and contented appearance, they are

well paid

for their labour. During my walk in the town I was

surrounded and

followed by hundreds of the natives, all anxious to get a view of the

foreigner. But except the inconvenience of the crowd I had nothing to

complain

of, for all were perfectly civil and in the best humour.

I spent the next few days in the

vicinity of

Nan-thin, and as it may be considered the centre of the great silk

country of

China, I shall endeavour now to give a description of the cultivation

and

appearance of the mulberry trees. The soil over all this district

is a strong yellow

loam, well mixed and enriched by vegetable matter; just such a soil as

produces

excellent wheat crops in England. The whole of the surface of the

country,

which at one period has been nearly a dead level, is now cut up, and

embankments formed for the cultivation of the mulberry. It appears to

grow

better upon the surface and sides of these embankments than upon level

land.

The low lands, which are, owing to the formation of these embankments,

considerably lower than the original level of the plain, are used for

the

production of rice and other grains and vegetables. It is therefore on

the

banks of canals, rice fields, small lakes and ponds, where the mulberry

is

generally cultivated, and where it seems most at home. But although

large

quantities of rice and other crops are grown in the silk districts, yet

the

country, when viewed from a distance, resembles a vast mulberry garden,

and

when the trees are in full leaf, it has a very rich appearance. The variety of mulberry

cultivated in this district

appears to be quite distinct from that which is grown in the southern

parts of

China and in the silk districts of India. Its leaves are much larger,

more

glossy, and have more firmness and substance than any other variety

which has

come under my notice. It may be that this circumstance has something to

do with

the superior quality of the silk produced in the Hoo-chow country, and

is

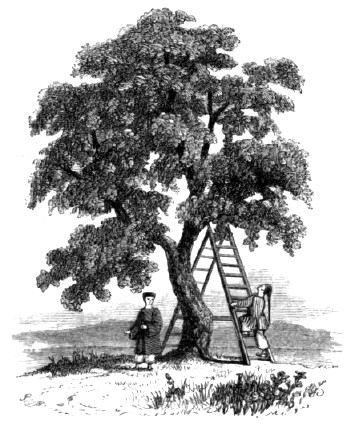

worthy of the notice of silk growers in other parts of the world. This peculiar variety is not

reproduced by seed, and

hence all the plantations are formed of grafted trees. Each plant is

grafted from

a foot to two feet above the ground, and rarely higher. The trees are

planted

in rows from five to six feet apart, and are allowed to grow from six

to ten

feet high only, for the convenience of gathering the leaves. In

training them

they are kept open in the centre; the general outline is circular, and

they are

not unlike some of those dwarf apple-trees which are common in European

gardens. The accompanying sketch gives a good representation of the

habit and

form of one of those trees which has attained its full size. The different methods of

gathering the leaves in

these districts are curious and instructive, and show clearly that the

cultivators well understand the laws of vegetable physiology. Leaves

are not

taken at all from plants in their young state, as this would be

injurious to

their future productiveness. In other instances a few leaves only are

taken

from the bushes, while the remainder are allowed to remain upon the

shoots

until the summer growth is completed. In the latter case the leaves are

invariably left at the ends of the shoots.

When the bushes have attained

their full size, the

young shoots with the leaves are clipped close off by the stumps, and

shoots

and leaves carried home together to the farm-yard to be plucked and

prepared

for the worms. In the case of young trees the leaves are generally

gathered by

the hand, while the shoots are left to grow on until the autumn. At

this period

all the plantations are gone over carefully; the older bushes are

pruned close

in to the stumps, while the shoots of the younger ones are only

shortened back

a little to allow them to attain to the desired height. The ground is

then

manured and well dug over. It remains in this state until the following

spring,

unless a winter crop of some kind of vegetable is taken off it. This is

frequently the case. Even in the spring and summer months it is not

unusual to

see crops of beans, cabbages, &c., growing under the mulberry

trees.

Mulberry

Tree. During the winter months the

trees are generally bare

and leafless. Those persons who are accustomed to live in countries

with marked

seasons, where the winters are cold, and where the great mass of

vegetation is

leafless, would not be struck with this circumstance in the silk

country of

China. But the view one gets in this country in the summer months,

after the

first clipping of the shoots, is curious and striking. As far as the

eye can

reach, in all directions, one sees nothing but bare stumps. It looks as

if some

pestilential vapour had passed over the plain and withered up the whole

of

these trees. And the view is rendered still more striking by the

beautiful

patches of lively green which are observed at this time in the

rice-fields and

on the banks of the canals. This system of clipping close in to the

stumps of

the old branches gives the trees a curious and deformed appearance. The

ends of

the branches swell out into a club-like form, and are much thicker

there than

they are lower down. The following sketch explains

the state in which

those trees are seen after they have been deprived of their stems and

leaves. After I had completed my

inspection of the country

near the town of Nan-tsin, I proceeded onwards to the west in the

direction of

Hoo-chow-foo. A few hours' sail on a wide and beautiful canal brought

me within

view of the mountain ranges which form the western boundary to the

great plain

of the Yang-tse-kiang, through which I had been passing for several

days. The

most striking hill which came first into view was crowned by a

seven-storied

pagoda. It had a large tree by its side, equally striking in the

distance, and

which had probably been planted when the pagoda was built. I afterwards

ascertained this to be the "maidenhair-tree" (Salisburia

adiantifolia), a tree which attains a large size in this part

of China, and

is extremely ornamental. As I neared Hoo-chow the general

aspect of the

country appeared very different from that through which I had been

travelling

for upwards of one hundred miles. The general level seemed higher, and

little

well-wooded hills adorned the surface of the country. I visited these

hills as

I went along for the purpose of examining their vegetation. In most

cases I

found pretty temples near their summits, surrounded with trees. From

these

spots the most charming views were obtained of the great mulberry

plain, the

city of Hoo-chow, and the mountain ranges which form the background

towards the

west. In one of the temples which I visited I found a priest who was a native of Ningpo, the town to which my servants belonged. He received us most cordially, and appeared glad to have an opportunity of talking with his townsmen, and getting all the news from his native place, which he had not visited for several years. In one of the cells of this temple we were shown a priest who had been submitting to voluntary confinement for nearly three years. It is not unusual to find devotees of this kind in many of the Buddhist temples of China. Although they never come out of their cells until the time of their confinement expires, they have no objection to see and converse with strangers at their little windows. The person whom we visited at this time received us with Chinese politeness, asked us to sit down on a chair placed outside his little cell, and gave us tea, on the surface of which various fragrant flowers were swimming. |