| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XVIII. Ascend the Lun-ke

river — A musical Buddhist high priest — Hoo-shan monastery — Its

silk-worms —

Mode of feeding them — General treatment — Their aversion to noise and

bright

light — The country embanked in all directions — A farmer's explanation

of this

— Town of Mei-che — Silk-worms begin to spin — Method of putting them

on straw

Artificial heat employed — Reeling process — Machine described —

Work-people —

Silk scenes in a monastery — Industrious Buddhist priests — Novel mode

of

catching fish — End of silk season — Price of raw silk where it is

produced.

I SPENT a week in the midst of

this beautiful

scenery, and experienced nothing but kindness and civility from the

hundreds of

natives with whom I came daily in contact. During this time I gained a

good

deal of information regarding the hilly districts to the westward,

which I intended

to penetrate before I left this part of the country. I found that a

river of

considerable size flowed up to the west gate of the city, and

apparently

emptied itself into the net-work of canals which cover this extensive

plain;

and I was informed that it was navigable for upwards of twenty miles to

boats

much larger than the one I was travelling in. My object now was to get

my boat

into that river, and as all these rivers and canals are connected this

was

accomplished without the least difficulty. We returned to the south

gate of

Hoo chow, where we found a wide

canal leading round the

walls to the west gate. Following this canal we soon skulled round, and

found

ourselves on a wide and deep river which takes its rise amongst the

hills in

the far west. It is called Lun-ke by the natives, and probably one of

its most

distant sources is near the celebrated Tein-muh-shan — a mountain said

to be

the highest in this part of China. In sailing up this river I

observed that the

plantations of mulberry still formed the staple crop of the country on

all the

flat lands which were raised above the surface of the rice-fields.

About sixty

le west of Hoo-chow-foo I observed a large monastery not

very far from the

banks of the river, and as it seemed situated in the midst of rich and

luxuriant vegetation, I determined to moor my boat to the banks of the

river,

and remain in the neighbourhood for a few days. As I was going up the

road in

the direction of the temple I met an old respectable-looking priest

carrying a

kind of flute or flageolet in his hand, which he induced now and then

to give

out not unmusical sounds. His head was shaven after the manner of the

priests

of Buddha; but the three nails on his left hand were each about two

inches in

length, denoting that he did not earn his bread by the sweat of his

brow, and

that in fact he was one of the superiors in the order to which he

belonged.

This old gentleman met me in the most dignified manner, and did not

express the

least surprise at seeing a foreigner so far from home. He asked me to

accompany

him home to his temple, and when we arrived there he introduced me to

his own

quarters and desired his servants to set tea and cakes before me. He

then led

me over all the halls and temples of the monastery, which, although

very

extensive, were in a most dilapidated condition. They were too much

like

buildings of this kind in other parts of the country to require any

further

notice. If there was little to notice in

these temples with

reference to Buddhism and its rites, there were objects of another kind

which

soon attracted my attention. The halls and outhouses of the monastery

seemed to

be converted for the time into a place for feeding silk-worms. Millions

of

these little animals were feeding in round sieves, placed one above

another in

open framework made for this purpose. So great was the number of the

worms that

every sieve — and there must have been many hundreds of them — was

crammed

quite full. In one large hall I observed the floor completely covered

with

worms. I shall never forget the peculiar sound which fell upon my ear

as I

opened the door of this hall. It was early in the morning, the worms

had been

just fed, and were at the time eagerly devouring the fresh leaves of

the

mulberry. Hundreds of thousands of little mouths were munching the

leaves, and

in the stillness around this sound was very striking and peculiar. The

place

too seemed so strange — a temple — a place of worship with many huge

idols,

some from twenty to thirty feet in height, looking down upon the scene

on the

floor. But to a Chinese there is nothing improper in converting a

temple into a

granary or a silk-worm establishment for a short time if it is

required, and I

suppose the gods of the place are supposed to look down with

approbation on

such scenes of peaceful industry. When from the large number of

worms it is necessary

to feed them on floors of rooms and halls, there is always a layer of

dry straw

laid down to keep them off the damp ground. This mode of treatment is

resorted

to from necessity, and not from choice. The sieves of the

establishment, used

in the framework I have already noticed, are greatly preferred. Whether the worms are fed on

sieves or on the floor

they are invariably cleaned every morning. All the remains of the

leafstalks of

the mulberry, the excrement of the animals, and other impurities, are

removed

before the fresh leaves are given. Much importance is attached to this

matter,

as it has a tendency to keep the worms in a clean and healthy

condition. The

Chinese are also very particular as regards the amount of light which

they

admit during the period the animals are feeding. I always observed the

rooms

were kept partially darkened, no bright light was allowed to penetrate.

In many

instances the owners were most unwilling to open the doors, for fear,

as they

said, of disturbing them; and they invariably cautioned me against

making any

unnecessary noise while I was examining them. At this time nearly all the

labour in this part of

the country was expended on the production of the silk-worm. In the

fields the

natives were seen in great numbers busily engaged in gathering the

leaves;

boats on the rivers were fraught with them; in the country market-towns

they

were exposed for sale in great quantities, and everything told that

they were

the staple article of production. On the other hand, every cottage,

farm-house,

barn and temple, was filled with its thousands of worms which were fed

and

tended with the greatest care. This part of the country is very

populous, villages

and small towns are scattered over it in every direction, and the

people have

the same dean and respectable appearance which I had already remarked

in other

parts of the silk districts. In making my observations on the rearing

of the

silk-worm I visited many hundreds of these towns and villages, and

never in one

instance had any complaint to make of incivility on the part of any one. After staying a few days in the

vicinity of the

temple of Hoo-shan — for such was its name — I gave my boatmen

directions to

move onwards further up the river. We passed a number of pretty towns

and

villages on its banks, and arrived at last at a place called Kin-hwa,

where I

remained for two days, and employed myself in making entomological

collections

and examining the productions of the district. We then went onwards to

a small

town mated Mei-che, which was as far as the river was navigable for

boats, and

from thirty to forty miles west from Hoo-chow-foo.

Here I moored my boat at a

little distance from the

town, and determined to remain in the neighbourhood long enough to

examine

everything of interest which might present itself. Although the country

was

comparatively level near the banks of the stream, yet I was now

surrounded on

all sides by hills, and the flat alluvial plain of the Yang-tse-Kiang

was quite

shut out from my view. In its general features it was rather curious

and

striking. Everywhere it was cut up into ponds and small lakes, and wide

embankments of earth seemed to cross it in all directions. At the first

view it

was difficult to account for this state of things, and I could not get

any

satisfactory reason for it, either from my servants or boatmen. I knew

well,

however, that the Chinese have a good and substantial reason for

everything

they do, and determined to apply to some farmer as the most likely

person to

enlighten me. One day when out on an excursion in the country I met an

intelligent-looking man, and to him I applied to solve the difficulty. "These embankments," said he,

"which

you now see cutting up the country in all directions, were formed many

hundred

years ago by our forefathers in order to protect themselves and their

crops

from being washed away by the floods. The vast plain, through which you

have

come from Shanghae, is scarcely any higher in level than where we now

stand,

for you will observe the tide ebbs and flows quite up to Mei-che. With

this

slow drainage for our mountain streams to the eastward we have

frequently a

large body of water pouring down upon us from the west, which overflows

the river's

banks and carries everything away before it. The embankments which you

observe

running in all directions are intended to check these floods, and

prevent them

from extending over the country." Upon giving the matter a little

consideration I had

no doubt that the explanation given by the Chinese farmer was the

correct one,

and that however strange these embankments might appear they were

necessary for

the safety of this part of the country. Mei-che is a long town on the

banks of the stream,

and as the river is no longer navigable for the low-country boats a

considerable business is done here in hill productions, which are

brought clown

for sale. They are put on board of boats here, and conveyed in them to

the

towns in the plains. This town appears to be almost

the western boundary

of the great silk country. Here the mulberry plantations, although

pretty

numerous, do not form the staple crop of the district, nor do they seem

to grow

with such luxuriance as they do further to the east about Hoo-chow and

Nantsin.

Large quantities of rice and other grains now take the place of the

mulberry.

In the mountains to the west considerable quantities of tea are

produced, and

fine bamboos which are sent down to the low country are made into

paper. A

mountain called Tein-muh-shan, celebrated amongst the Chinese for its

height

and for its temples, lies to the west of this, and further west still

is the

great green-tea country of Hwuy-chow, which I examined during my former

visit

to China. On my way up from Hoo-chow-foo

to Mei-che, and about

the 23rd of June, I observed that many of the worms had ceased to feed

and were

commencing to spin. The first indication of this change is made

apparent to the

natives by the bodies of the little animals becoming more clear and

almost

transparent. When this change takes place, they are picked, one by one,

out of

the sieves, and placed upon bundles of straw to form their cocoons.

These

bundles of straw, which are each about two feet in length, are bound

firmly in

the middle; the two ends are cut straight and then spread out like a

broom, and

into these ends the worms are laid, when they immediately fix

themselves and

begin to spin. During this process I observed the under side of the

framework

on which the bundles of straw were placed surrounded with cotton cloth

to

prevent the cold draught from getting to the worms. In some instances

small

charcoal fires were lighted and placed tinder the frame inside the

cloth, in

order to afford further warmth. In some of the cottages the straw

covered with

spinning worms was laid, in the sun under the verandahs in front of the

doors. In a few days after the worms

are put upon the straw

they have disappeared in the cocoons and have ceased to spin. The

reeling

process now commences, and machines for this purpose were seen in

almost every

cottage. This apparatus may be said to consist of four distinct parts,

or

rather, I may divide it into these for the purpose of describing it.

There is,

first, the pan of hot water into which the cocoons are thrown ; second,

the

little loops or eyes through which the threads pass; third, a lateral

or

horizontal movement, in order to throw the silk in a zigzag manner over

the

wheel; and lastly the wheel itself, which is square. Two men, or a man

and

woman, are generally employed at each wheel. The business of one is to

attend

to the fire and to add fresh cocoons as the others are wound off. The

most

expert workman drives the machine with his foot and attends to the

threads as

they pass through the loops over on to the wheel. Eight, ten, and

sometimes

twelve cocoons are taken up to form one thread, and as one becomes

exhausted,

another is taken up to supply its place. Three, and sometimes four, of

such

threads are passing over on to the wheel at the same time. The lateral

or zig-zag

movement of the machine throws the threads in that way on the wheel,

and I

believe this is considered a great improvement upon the Canton method,

in which

the threads are thrown on in a parallel manner. The water in the pan into which

the cocoons are first

thrown is never allowed to boil, but it is generally very near the

boiling

point. I frequently tried it and found it much too hot for my fingers

to remain

in it. A slow fire of charcoal is also placed under the wheel. As the

silk is

winding, this fire is intended to dry off the superfluous moisture

which the

cocoons have imbibed in the water in which they were immersed. During the time I was in the

silk country at this

time I was continually visiting the farmhouses and cottages in which

the reeling

of silk was going on. As silk is a very valuable production, it is

reeled with

more than ordinary care, and I observed that in almost all instances a

clean,

active, and apparently clever workman was entrusted with the care of

the

reeling process. The old temple at Hoo-shan,

which I visited again on

my way down, was in a state of great excitement and bustle. The

quantity of

silk produced here was very large, and all hands were employed in

reeling and

sorting it. The priests themselves, who generally are rather averse to

work of

any kind, were obliged to take their places at the wheel or the fire.

But as

the silk was their own they seemed, notwithstanding their habitual

indolence,

to work with hearty goodwill. My old friend the Superior, however, was

exempt from labour. When I called, and found all the verandahs and

courts in a

bustle, he was quietly smoking his pipe and sipping his tea with his

favourite

flageolet by his side. I remained with him during the heat of the day,

and in

the evening he walked down with me to the river side where my boat was

moored.

He readily accepted an invitation to come on board, and while there

took a

great fancy to a copy of 'Punch' and the 'Illustrated London News.' I

need not

say I made him a present of both papers, and sent him away highly

delighted. My

boat now shot out into the stream, and as we sailed slowly down I could

hear

the wild and not unpleasing strains of my friends flageolet as he

wended his

way homewards through the woods.

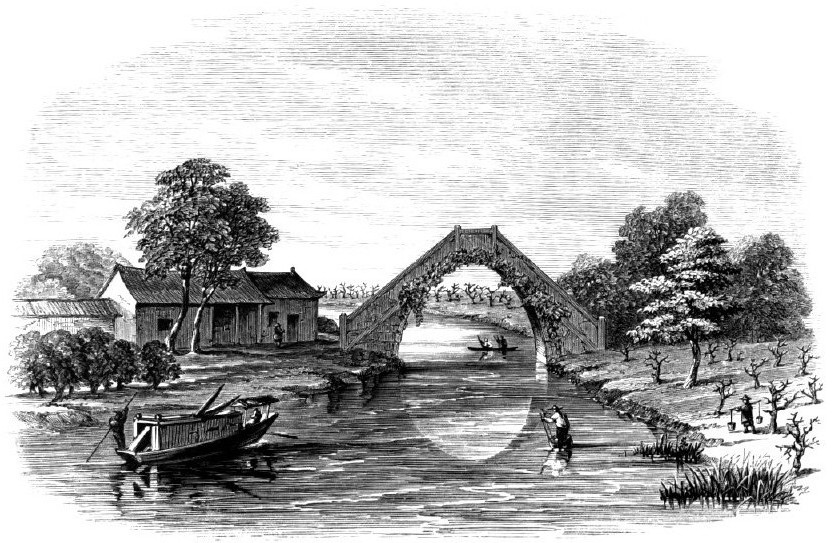

On our way down the river that

night we came upon

some people fishing in a manner so curious that I must endeavour to

describe

it. The boats used for this purpose were long and narrow. Each had a

broad

strip of white canvas stretched along the right side, and dipping

towards the

water at an angle of from thirty to forty degrees. On the other side of

the

boat a net, corresponding in size with the white cloth, was stretched

along

above the bulwarks. A man sat in the stern of each boat and brought his

weight

to bear on the starboard side, which had the effect of pressing the

white

canvas into the water and raising the net on the opposite side. A small

paddle

was used for propelling the boat through the water. This will be well

understood by a glance at the accompanying sketch.

As we approached these strange

fishermen, I desired

my boatmen to take in our sail, and as my boat lay still on the smooth

surface

of the water, I watched their proceedings with much interest. It was a

fine,

clear night, and I could see distinctly the white canvas shining

through the

water, although several inches beneath its surface. The fishermen sat

motionless and silent, and scarcely noticed us when we joined them, so

intent

were they upon their work. We had not remained above a minute in the

position

we had taken up, when I heard a splash in the water, and distinctly saw

a fish

jump over the boat and get caught by the net on its opposite side. The

object

in constructing the boats in the manner I have described was now

apparent. It

seemed that the white canvas, which dipped like a painted board into

the water,

had the effect of attracting and decoying the fish in some peculiar

manner, and

caused them to leap over it. But as the boats were low and narrow, it

was

necessary to have a net stretched on the opposite side to prevent the

fish from

leaping over them altogether and escaping again into the stream. Each

fish, as

it took the fatal leap, generally struck against the net and fell

backward into

the boat. My boatmen and servants looked

on this curious method

of catching fish with as much interest as I did myself, and could not

refrain

from expressing their delight rather noisily when a poor fish got

caught. The

fishermen themselves remained motionless as statues, and scarcely

noticed us,

except to beg we would not make any noise, as it prevented them from

catching

fish. We watched these fishermen for

upwards of an hour,

and then asked them to sell us some fish for supper. Their little boats

were

soon alongside of ours, and we purchased some of the fish which we had

seen

caught in this extraordinary and novel manner. On the following morning, when I

awoke, I found

myself quietly at anchor close by the west gate of Hoo-chow-foo, my

boatmen

having worked all night. I spent the next few days in the country to

the

northward bordering on the T'aihoo lake, and partly near the town of

Nan-tsin,

being anxious to see the end of the silk season. About the eighth, or

from that

to the tenth of July, the winding of the cocoons had ceased almost

everywhere,

and a few days after this there was scarcely a sign of all that life

and bustle

which is visible everywhere during the time that the silk is in hand.

The clash

of the winding-machines, which used to be heard in every cottage,

farmhouse, and

temple, had now ceased; the furnaces, pans, and wheels, with all the

other

parts of the apparatus in common use during the winding season, had

been

cleared away, and a stranger visiting that country now could scarcely

have

believed that such a busy bustling scene had been acting only a few

days

before. During my perigrinations in the

silk country I made

many inquiries amongst the natives as to the price of raw silk in the

districts

where it is produced. An inquiry of this kind is always rather

difficult in a

country like China, where the natives are too practical to believe one

is

making such an inquiry merely for the purpose of gaining information.

On

several occasions the reply to my question was another, wishing to know

whether

I wanted to buy. Most of the natives with whom I came in contact firmly

believed my object in coming to the silk-country was to purchase silks;

and

neither my assurances to the contrary nor those of my servants, who

were

generally appealed to on the subject, were sufficient to make them

change their

opinion. I believe, however, the information I gleaned from various

quarters at

different times will be found to be tolerably correct. At Mei-che the

price was

said to range from twelve to eighteen dollar's for 100 taels of silk.

At Hoo-chow

and Nantsin, where the silk is of a superior quality, the prices in

1856 were

from eighteen to twenty-two dollars for 100 taels. The price of raw

silk, like

that of everything else, no doubt depends in a great measure upon the

supply

and demand, and varies accordingly. |