| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2014 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

TO

W-A-AT T

You are a

child, old Friend — a child!

As light of heart, as free, as wild; As credulous of fairy tale; As simple in your faith, as frail In reason; jealous, petulant; As crude in manner; ignorant, Yet wise in love; as rough, as mild — You are a child! You are a man, old Friend — a man! Ah, sure in richer tide ne'er ran The blood of earth's nobility, Than through your veins; intrepid, free; In counsel, prudent; proud and tall; Of passions full, yet ruling all; No stauncher friend since time began; You are a MAN! THE VOYAGE On September

nineteenth a little

stranger whose expected advent was keeping me at home arrived in the

person of

our first-born daughter. For two or three weeks preceding and following

this

event Muir was busy writing his summer notes and finishing his pencil

sketches,

and also studying the flora of the islands. It was a season of constant

rains

when the saanah, the southeast rain-wind, blew a gale. But these stormy

days

and nights, which kept ordinary people indoors, always lured him out

into the

woods or up the mountains. One wild night,

dark as Erebus, the

rain dashing in sheets and the wind blowing a hurricane, Muir came from

his room

into ours about ten o'clock with his long, gray overcoat and his Scotch

cap on. "Where now?" I

asked. "Oh, to the top

of the

mountain," he replied. "It is a rare chance to study this fine

storm." My

expostulations were in vain. He

rejected with scorn the proffered lantern: "It would spoil the

effect." I retired at my usual time, for I had long since learned not

to

worry about Muir. At two o'clock in the morning there came a hammering

at the

front door. I opened it and there stood a group of our Indians,

rain-soaked and

trembling — Chief

Tow-a-att, Moses, Aaron, Matthew, Thomas. "Why, men," I

cried,

"what's wrong? What brings you here?" "We want you

play (pray),"

answered Matthew. I brought them

into the house, and,

putting on my clothes and lighting the lamp, I set about to find out

the

trouble. It was not easy. They were greatly excited and frightened. "We scare. All

Stickeen scare;

plenty cly. We want you play God; plenty play." By dint of much

questioning I gathered

at last that the whole tribe were frightened by a mysterious light

waving and

flickering from the top of the little mountain that overlooked

Wrangell; and

they wished me to pray to the white man's God and avert dire calamity. "Some miner has

camped

there," I ventured. An eager chorus

protested; it was not

like the light of a camp-fire in the least; it waved in the air like

the wings

of a spirit. Besides, there was no gold on the top of a hill like that;

and no

human being would be so foolish as to camp up there on such a night,

when there

were plenty of comfortable houses at the foot of the hill. It was a

spirit, a

malignant spirit. Suddenly the

true explanation flashed

into my brain, and I shocked my Indians by bursting into a roar of

laughter. In

imagination I could see him so plainly — John Muir, wet

but happy,

feeding his fire with spruce sticks, studying and enjoying the storm!

But I

explained to my natives, who ever afterwards eyed Muir askance, as a

mysterious

being whose ways and motives were beyond all conjecture. "Why does this

strange man go into

the wet woods and up the mountains on stormy nights?" they asked.

"Why does he wander alone on barren peaks or on dangerous

ice-mountains?

There is no gold up there and he never takes a gun with him or a pick.

Icta

mamook — what make? Why — why?" The first week

in October saw the

culmination of plans long and eagerly discussed. Almost the whole of

the

Alexandrian Archipelago, that great group of eleven hundred wooded

islands that

forms the southeastern cup-handle of Alaska, was at that time a terra

incognita. The only seaman's chart of the region in existence was that

made by

the great English navigator, Vancouver, in 1807. It was a wonderful

chart,

considering what an absurd little sailing vessel he had in which to

explore

those intricate waters with their treacherous winds and tides. But Vancouver's

chart was hastily made,

after all, in a land of fog and rain and snow. He had not the modern

surveyor's

instruments, boats or other helps. And, besides, this region was

changing more

rapidly than, perhaps, any other part of the globe. Volcanic islands

were being

born out of the depths of the ocean; landslides were filling up

channels

between the islands; tides and rivers were opening new passages and

closing old

ones; and, more than all, those mightiest tools of the great Engineer,

the

glaciers, were furrowing valleys, dumping millions of tons of silt into

the

sea, forming islands, promontories and isthmuses, and by their

recession

letting the sea into deep and long fiords, forming great bays, inlets

and

passages, many of which did not exist in Vancouver's time. In certain

localities the living glacier stream was breaking off bergs so fast

that the

resultant bays were lengthening a mile or more each year. Where

Vancouver saw

only a great crystal wall across the sea, we were to paddle for days up

a long

and sinuous fiord; and where he saw one glacier, we were to find a

dozen. My mission in

the proposed voyage of

discovery was to locate and visit the tribes and villages of Thlingets

to the

north and west of Wrangell, to take their census, confer with their

chiefs and

report upon their condition, with a view to establishing schools and

churches

among them. The most of these tribes had never had a visit from a

missionary,

and I felt the eager zeal an Eliot or a Martin at the prospect of

telling them

for the first time the Good News. Muir's mission was to find and study

the

forests, mountains and glaciers. I also was eager to see these and

learn about

them, and Muir was glad to study the natives with me — so our plans

fitted into each

other well. "We are going

to write some

history, my boy," Muir would say to me. "Think of the honor! We have

been chosen to put some interesting people and some of Nature's

grandest scenes

on the page of human record and on the map. Hurry! We are daily losing

the most

important news of all the world." In many

respects we were most congenial

companions. We both loved the same poets and could repeat, verse about,

many

poems of Tennyson, Keats, Shelley and Burns. He took with him a volume

of

Thoreau, and I one of Emerson, and we enjoyed them together. I had my

printed

Bible with me, and he had his in his head — the result of

a Scotch

father's discipline. Our studies supplemented each other and our tastes

were

similar. We had both lived clean lives and our conversation together

was sweet

and high, while we both had a sense of humor and a large fund of

stories. But Muir's

knowledge of Nature and his

insight into her plans and methods were so far beyond mine that, while

I was

organizer and commander of the expedition, he was my teacher and guide

into the

inner recesses and meanings of the islands, bays and mountains we

explored

together. Our ship for

this voyage of discovery,

while not so large as Vancouver's, was much more shapely and manageable

— a kladushu

etlan (six fathom)

red-cedar canoe. It belonged to our captain, old Chief Tow-a-att, a

chief who

had lately embraced Christianity with his whole heart — one of the

simplest, most

faithful, dignified and brave souls I ever knew. He fully expected to

meet a

martyr's death among his heathen enemies of the northern islands; yet

he did

not shrink from the voyage on that account. His crew

numbered three. First in

importance was Kadishan, also a chief of the Stickeens, chosen because

of his

powers of oratory, his kinship with Chief Shathitch of the Chilcat

tribe, and

his friendly relations with other chiefs. He was a born courtier,

learned in

Indian lore, songs and customs, and able to instruct me in the proper

Thlinget

etiquette to suit all occasions. The other two were sturdy young men — Stickeen John,

our

interpreter, and Sitka Charley. They were to act as cooks, camp-makers,

oarsmen, hunters and general utility men. We stowed our

baggage, which was not

burdensome, in one end of the canoe, taking a simple store of

provisions — flour, beans,

bacon, sugar,

salt and a little dried fruit. We were to depend upon our guns,

fishhooks,

spears and clamsticks for other diet. As a preliminary to our palaver

with the

natives we followed the old Hudson Bay custom, then firmly established

in the

North. We took materials for a potlatch, — leaf-tobacco,

rice and sugar.

Our Indian crew laid in their own stock of provisions, chiefly dried

salmon and

seal-grease, while our table was to be separate, set out with the white

man's

viands. We did not get

off without trouble.

Kadishan's mother, who looked but little older than himself, strongly

objected

to my taking her son on so perilous a voyage and so late in the fall,

and when

her scoldings and entreaties did not avail she said: "If anything

happens

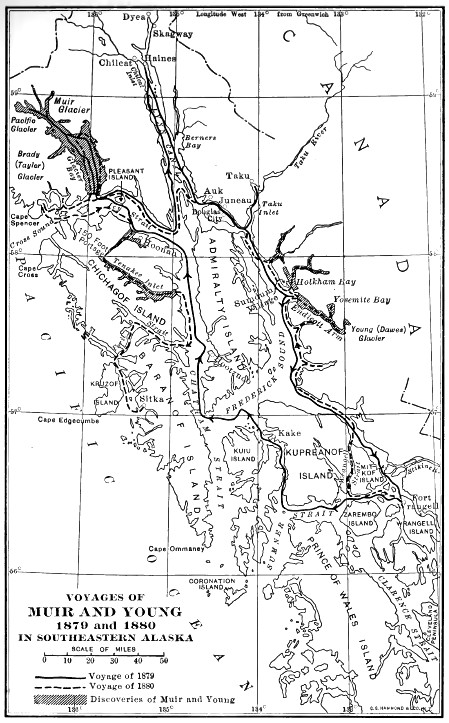

to my son, I will take your baby as mine in payment."  VOYAGES OF MUIR AND YOUNG 1879 and 1880 IN SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA One sunny

October day we set our prow

to the unknown northwest. Our hearts beat high with anticipation. Every

passage

between the islands was a corridor leading into a new and more

enchanting room

of Nature's great gallery. The lapping waves whispered enticing

secrets, while

the seabirds screaming overhead and the eagles shrilling from the sky

promised wonderful

adventures. The voyage

naturally divides itself

into the human interest and the study of nature; yet the two constantly

blended

throughout the whole voyage. I can only select a few instances from

that trip

of six weeks whose every hour was new and strange. Our captain,

taciturn and self-reliant,

commanded Muir's admiration from the first. His paddle was sure in the

stern,

his knowledge of the wind and tide unfailing. Whenever we landed the

crew would

begin to dispute concerning the best place to make camp. But old

Tow-a-att,

with the mast in his hand, would march straight as an arrow to the

likeliest

spot of all, stick down his mast as a tent-pole and begin to set up the

tent,

the others invariably acquiescing in his decision as the best possible

choice. At our first

meal Muir's sense of humor

cost us one-third of a roll of butter. We invited our captain to take

dinner

with us. I got out the bread and other viands, and set the two-pound

roll of

butter beside the bread and placed both by Tow-a-att. He glanced at the

roll of

butter and at the three who were to eat, measured with his eye

one-third of the

roll, cut it off with his hunting knife and began to cut it into

squares and

eat it with great gusto. I was about to interfere and show him the use

we made

of butter, but Muir stopped me with a wink. The old chief calmly

devoured his

third of the roll, and rubbing his stomach with great satisfaction

pronounced

it "hyas klosh (very good) glease." Of necessity we

had chosen the rainiest

season of the year in that dampest climate of North America, where

there are

two hundred and twenty-five rainy days out of the three hundred and

sixty-five.

During our voyage it did not rain every day, but the periods of

sunshine were

so rare as to make us hail them with joyous acclamation. We steered our

course due westward for

forty miles, then through a sinuous, island-studded passage called

Rocky

Strait, stopping one day to lay in a supply of venison before sailing

on to the

village of the Kake Indians. My habit throughout the voyage, when

coming to a

native town, was to find where the head chief lived, feed him with rice

and

regale him with tobacco, and then induce him to call all his chiefs and

head

men together for a council. When they were all assembled I would give

small

presents of tobacco to each, and then open the floodgate of talk,

proclaiming

my mission and telling them in simplest terms the Great New Story. Muir

would

generally follow me, unfolding in turn some of the wonders of God's

handiwork

and the beauty of clean, pure living; and then in turn, beginning with

the head

chief, each Indian would make his speech. We were received with joy

everywhere,

and if there was suspicion at first old Tow-a-att's tearful pleadings

and

Kadishan's oratory speedily brought about peace and unity. These palavers

often lasted a whole day

and far into the night, and usually ended with our being feasted in

turn by the

chief in whose house we had held the council. I took the census of each

village, getting the heads of the families to count their relatives

with the

aid of beans, — the large

brown beans representing men, the large white

ones, women, and the small Boston beans, children. In this manner the

first

census of southeastern Alaska was taken. Before starting

on the voyage, we heard

that there was a Harvard graduate, bearing an honored New England name,

living

among the Kake Indians on Kouyou Island. On arriving at the chief town

of that

tribe we inquired for the white man and were told that he was camping

with the

family of a sub-chief at the mouth of a salmon stream. We set off to

find him.

As we neared the shore we saw a circular group of natives around a fire

on the

beach, sitting on their heels in the stoical Indian way. We landed and

came up

to them. Not one of them deigned to rise or show any excitement at our

coming.

The eight or nine men who formed the group were all dressed in colored

four-dollar blankets, with the exception of one, who had on a ragged

fragment

of a filthy, two-dollar, Hudson Bay blanket. The back of this man was

towards

us, and after speaking to the chief, Muir and I crossed to the other

side of

the fire, and saw his face. It was the white man, and the ragged

blanket was

all the clothing he had upon him! An effort to open conversation with

him

proved futile. He answered only with grunts and mumbled monosyllables.

Thus the

most filthy, degraded, hopelessly lost savage that we found in this

whole

voyage was a college graduate of great New England stock! "Lift a stone

to mountain height

and let it fall," said Muir, "and it will sink the deeper into the

mud." At Angoon, one

of the towns of the

Hootz-noo tribe, occurred an incident of another type. We found this

village

hilariously drunk. There was a very stringent prohibition law over

Alaska at

that time, which absolutely forbade the importation of any spirituous

liquors

into the Territory. But the law was deficient in one vital respect — it did not

prohibit the

importation of molasses; and a soldier during the military occupancy of

the

Territory had instructed the natives in the art of making rum. The

method was

simple. A five-gallon oil can was taken and partly filled with molasses

as a

base; into that alcohol was placed (if it were obtainable), dried

apples,

berries, potatoes, flour, anything that would rot and ferment; then, to

give it

the proper tang, ginger, cayenne pepper and mustard were added. This

mixture

was then set in a warm place to ferment. Another oil can was cut up

into long

strips, the solder melted out and used to make a pipe, with two or

three turns

through cool water, — forming the

worm, and the still. Talk

about your forty-rod whiskey — I have seen

this "hooch," as

it was called because these same Hootz-noo natives first made it, kill

at more

than forty rods, for it generally made the natives fighting drunk. Through the

large company of screaming,

dancing and singing natives we made our way to the chief's house. By

some

miracle this majestic-looking savage was sober. Perhaps he felt it

incumbent

upon him as host not to partake himself of the luxuries with which he

regaled

his guests. He took us hospitably into his great community house of

split cedar

planks with carved totem poles for corner posts, and called his young

men to

take care of our canoe and to bring wood for a fire that he might feast

us. The

wife of this chief was one of the finest looking Indian women I have

ever met, — tall,

straight, lithe and

dignified. But, crawling about on the floor on all fours, was the most

piteous

travesty of the human form I have ever seen. It was an idiot boy,

sixteen years

of age. He had neither the comeliness of a beast nor the intellect of a

man.

His name was Hootz-too (Bear Heart), and indeed all his motions were

those of a

bear rather than of a human being. Crossing the floor with the swinging

gait of

a bear, he would crouch back on his haunches and resume his constant

occupation

of sucking his wrist, into which he had thus formed a livid hole. When

disturbed at this horrid task he would strike with the claw-like

fingers of the

other hand, snarling and grunting. Yet the beautiful chieftainess was

his

mother, and she loved him. For sixteen years she had cared for this

monster,

feeding him with her choicest food, putting him to sleep always in her

arms,

taking him with her and guarding him day and night. When, a short time

before

our visit, the medicine men, accusing him of causing the illness of

some of the

head men of the village, proclaimed him a witch, and the whole tribe

came to

take and torture him to death, she fought them like a lioness, not

counting her

own life dear unto her, and saved her boy. When I said to

her thoughtlessly,

"Oh, would you not be relieved at the death of this poor idiot boy?"

she saw in my words a threat, and I shall never forget the pathetic,

hunted

look with which she said: "Oh, no, it

must not be; he shall

not die. Is he not my son, uh-yeet-kutsku (my dear little son)?" If our voyage

had yielded me nothing

but this wonderful instance of mother-love, I should have counted

myself richly

repaid. One more human

story before I come to

Muir's part. It was during the latter half of the voyage, and after our

discovery of Glacier Bay. The climax of the trip, so far as the

missionary

interests were concerned, was our visit to the Chilcat and Chilcoot

natives on

Lynn Canal, the most northern tribes of the Alexandrian Archipelago.

Here

reigned the proudest and worst old savage of Alaska, Chief Shathitch.

His

wealth was very great in Indian treasures, and he was reputed to have

cached

away in different places several houses full of blankets, guns, boxes

of beads,

ancient carved pipes, spears, knives and other valued heirlooms. He was

said to

have stored away over one hundred of the elegant Chilcat blankets woven

by hand

from the hair of the mountain goat. His tribe was rich and

unscrupulous. Its

members were the middle-men between the whites and the Indians of the

Interior.

They did not allow these Indians to come to the coast, but took over

the

mountains articles purchased from the whites — guns,

ammunition, blankets,

knives and so forth — and bartered

them for furs. It was

said that they claimed to be the manufacturers of these wares and so

charged

for them what prices they pleased. They had these Indians of the

Interior in a

bondage of fear, and would not allow them to trade directly with the

white men.

Thus they carried out literally the story told of Hudson Bay traffic, — piling beaver

skins to the

height of a ten-dollar Hudson Bay musket as the price of the musket.

They were

the most quarrelsome and warlike of the tribes of Alaska, and their

villages

were full of slaves procured by forays upon the coasts of Vancouver

Island,

Puget Sound, and as far south as the mouth of the Columbia River. I was

eager

to visit these large and untaught tribes, and establish a mission among

them. About the first

of November we came in

sight of the long, low-built village of Yin-des-tuk-ki. As we paddled

up the

winding channel of the Chilcat River we saw great excitement in the

town. We

had hoisted the American flag, as was our custom, and had put on our

best apparel

for the occasion. When we got within long musket-shot of the village we

saw the

native men come rushing from their houses with their guns in their

hands and

mass in front of the largest house upon the beach. Then we were greeted

by what

seemed rather too warm a reception — a shower of

bullets falling

unpleasantly around us. Instinctively Muir and I ceased to paddle, but

Tow-a-att commanded, "Ut-ha, ut-ha! — pull, pull!"

and slowly,

amid the dropping bullets, we zigzagged our way up the channel towards

the

village. As we drew near the shore a line of runners extended down the

beach to

us, keeping within shouting distance of each other. Then came the

questions

like bullets — "Gusu-wa-eh? — Who are you?

Whence do you

come? What is your business here?" And Stickeen John shouted back the

reply:  Chief Shathitch was said to have over one hundred of the elegant Chilcat blankets, woven by hand, from the hair of the mountain goat The answer was

shouted back along the

line, and then returned a message of greeting and welcome. We were to

be the

guests of the chief of Yin-des-tuk-ki, old Don-na-wuk (Silver Eye), so

called

because he was in the habit of wearing on all state occasions a huge

pair of

silver-bowed spectacles which a Russian officer had given him. He

confessed he

could not see through them, but thought they lent dignity to his

countenance.

We paddled slowly up to the village, and Muir and I, watching with

interest,

saw the warriors all disappear. As our prow touched the sand, however,

here

they came, forty or fifty of them, without their guns this time, but

charging

down upon us with war-cries, "Hoo-hooh, hoo-hooh," as if they were

going to take us prisoners. Dashing into the water they ranged

themselves along

each side of the canoe; then lifting up our canoe with us in it they

rushed

with excited cries up the bank to the chief's house and set us down at

his

door. It was the Thlinget way of paying us honor as great guests. Then we were

solemnly ushered into the

presence of Don-na-wuk. His house was large, covering about fifty by

sixty feet

of ground. The interior was built in the usual fashion of a chief's

house — carved corner

posts, a square

of gravel in the center of the room for the fire surrounded by great

hewn cedar

planks set on edge; a platform of some six feet in width running clear

around

the room; then other planks on edge and a high platform, where the

chieftain's

household goods were stowed and where the family took their repose. A

brisk

fire was burning in the middle of the room; and after a short palaver,

with

gifts of tobacco and rice to the chief, it was announced that he would

pay us

the distinguished honor of feasting us first. It was a

never-to-be-forgotten banquet.

We were seated on the lower platform with our feet towards the fire,

and before

Muir and me were placed huge washbowls of blue Hudson Bay ware. Before

each of

our native attendants was placed a great carved wooden trough, holding

about as

much as the washbowls. We had learned enough Indian etiquette to know

that at

each course our respective vessels were to be filled full of food, and

we were

expected to carry off what we could not devour. It was indeed a "feast

of

fat things." The first course was what, for the Indian, takes the place

of

bread among the whites, — dried salmon.

It was served, a whole

washbowlful for each of us, with a dressing of seal-grease. Muir and I

adroitly

manœuvred

so as to get our salmon and seal-grease served separately; for our

stomachs had

not been sufficiently trained to endure that rancid grease. This course

finished, what was left was dumped into receptacles in our canoe and

guarded

from the dogs by young men especially appointed for that purpose. Our

washbowls

were cleansed and the second course brought on. This consisted of the

back fat

of the deer, great, long hunks of it, served with a gravy of

seal-grease. The

third course was little Russian potatoes about the size of walnuts,

dished out

to us, a washbowlful, with a dressing of seal-grease. The final course

was the

only berry then in season, the long fleshy apple of the wild rose

mellowed with

frost, served to us in the usual quantity with the invariable sauce of

seal-grease. "Mon, mon!"

said Muir aside

to me, "I'm fashed we'll be floppin' aboot i' the sea, whiles, wi'

flippers an' forked tails." When we had

partaken of as much of this

feast of fat things as our civilized stomachs would stand, it was

suddenly

announced that we were about to receive a visit from the great chief of

the

Chilcats and the Chilcoots, old Chief Shathitch (Hard-to-Kill). In

order to

properly receive His Majesty, Muir and I and our two chiefs were each

given a

whole bale of Hudson Bay blankets for a couch. Shathitch made us wait a

long

time, doubtless to impress us with his dignity as supreme chief. The heat of the

fire after the wind and

cold of the day made us very drowsy. We fought off sleep, however, and

at last

in came stalking the biggest chief of all Alaska, clothed in his robe

of state,

which was an elegant chinchilla blanket; and upon its yellow surface,

as the

chief slowly turned about to show us what was written thereon, we were

astonished to see printed in black letters these words, "To Chief

Shathitch,

from his friend, William H. Seward!" We learned afterwards that Seward,

in

his voyage of investigation, had penetrated to this far-off town, had

been

received in royal state by the old chief and on his return to the

States had

sent back this token of his appreciation of the chief's hospitality.

Whether

Seward was regaled with viands similar to those offered to us, history

does not

relate. To me the

inspiring part of that voyage

came next day, when I preached from early morning until midnight, only

occasionally

relieved by Muir and by the responsive speeches of the natives. "More, more;

tell us more,"

they would cry. "It is a good talk; we never heard this story

before." And when I would inquire, "Of what do you wish me now to

talk?" they would always say, "Tell us more of the Man from Heaven

who died for us." Runners had

been sent to the Chilcoot

village on the eastern arm of Lynn Canal, and twenty-five miles up the

Chilcat

River to Shathitch's town of Klukwan; and as the day wore away the

crowd of Indians

had increased so greatly that there was no room for them in the large

house. I

heard a scrambling upon the roof, and looking up I saw a row of black

heads

around the great smoke-hole in the center of the roof. After a little a

ripping, tearing sound came from the sides of the building. They were

prying

off the planks in order that those outside might hear. When my voice

faltered

with long talking Tow-a-att and Kadishan took up the story, telling

what they

had learned of the white man's religion; or Muir told the eager natives

wonderful things about what the great one God, whose name is Love, was

doing

for them. The all-day meeting was only interrupted for an hour or two

in the

afternoon, when we walked with the chiefs across the narrow isthmus

between Pyramid

Harbor and the eastern arm of Lynn Canal, and I selected the harbor,

farm and

townsite now occupied by Haines mission and town and Fort William H.

Seward.

This was the beginning of the large missions of Haines and Klukwan. |