| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER V. FRUITS. _____________________________ Propagation, Planting, Cultivation. PROPAGATION. 273. All the Fruits to be treated of here, except the Strawberry, are the produce of trees or of woody plants. All these may be propagated from seed, and some are so propagated. But others are usually propagated by cuttings, slips, layers, or suckers; or by budding or grafting upon stocks. 274. The methods of propagation, best suited to each kind, will be mentioned under the name of the kinds respectively; and, therefore, in this place I am to describe the several methods generally, and the management suited to each. 275. When the propagation is from seed, the sowing should be in good ground, finely broken, and the seed should by no means be sown too thick. How to save and preserve the seed will be spoken of under the names of the several trees. But, the seed being good, it should be well sown, well covered, and carefully preserved from mice and other vermin. 276. CUTTINGS are short pieces, cut in the spring, from shoots of the last year, and it is, in most cases, best, if they have a joint or two of the former year's wood, at the bottom of them. The cutting should have altogether, about six joints, or buds; and three of these should be under ground when planted. The cuts should be performed with a sharp knife, so that there may be nothing ragged or bruised about either wood or bark. The time for taking off cuttings is that of the breaking up of the frost. They should be planted in a shady place, and watered with rain water, in dry weather, until they have got shoots several inches long, \\hen they have such shoots they have roots, and when they have these, no more watering is necessary. Besides these occasional waterings, the ground should, especially in hot countries, be covered with leaves of trees, or muck, or something that will keep the ground cool during the hot and dry weather. 277. SLIPS differ from cuttings in this, that the former are not cut, but pulled, from the tree. You take a shoot of the last year, and pull it downwards, and thus slip it off. You trim the ragged back off; then shorten the shoot so that it have six joints left; and then plant it and manage it in the same manner as directed for cuttings. The season for the work is also the same. 273. LAYERS. You take a limb, or branch of a tree, in the fall, or early in Spring, and pull it down in such a way as to cause its top, or small shoots and twigs to lie upon the ground. Then fasten the limb down by a peg or two, so that its own force will not raise it up. Then prune off all the small branches and shoots that stick upright; and, having a parcel of shoots lying horizontally, lay earth upon the whole, all along upon the limb from the point where it begins to touch the ground, and also upon all the bottoms of all the shoots. Then cut the shoots off at the points, leaving only two or three joints or buds beyond the earth. The earth, laid on should be good, and the ground should be fresh-digged and made very fine and smooth before the branches be laid upon it. The earth, laid on, should be from six inches to a foot thick. If the limb, or mother branch, be very stubborn, a little cut on the lower side of it will make it the more easy to be held down. The ground should be kept clean from weeds, and as cool as possible in hot weather. Perhaps rocks or stones (not large) are the best and coolest covering. These layers will be ready to take up and plant out as trees after they have been laid a year. 279. SUCKERS are, in general, but poor things, whether in the forest, or in the fruit garden. They are shoots that come up from the roots, at a distance from the stem of the tree, or, at least, they do not come out of that stem. They run to wood and to suckers more than trees do that are raised in any other way. Fruit trees raised from suckers do not bear so abundantly, and such good fruit, as trees raised from cuttings, slips or layers. A sucker is, in fact, a little tree with more or less of root to it, and is, of course, to be treated as a tree. 280. BUDDING. To have fruit trees by this method, or by that of grafting, you must first have stocks; that is to say, a young tree to bud or graft upon. What are the sorts of stocks proper for the sorts of fruit-trees respectively will be mentioned under the names of the latter. The stock is a young tree of some sort or other, and the bud is put into the bark on the side of this young tree during the summer; and not before the bud be full and plump. The work may generally be done all through the months of July and August, and, perhaps, later. 281. GRAFTING is the joining of a cutting of one to another tree in such a way as that the tree, on which the cutting is placed, sends up its sap into the cutting, and makes it grow and become a tree. Now, as to the way, in which this, and the way in which budding, is done, they cannot upon any principle consistent with common sense, become matter of written description. Each is a mechanical operation, embracing numerous movements of the arms, hands, and fingers, and is no more to be taught by written directions than the making of a chest of drawers is. To read a full and minute account of the acts of budding and grafting would require ten times the space of time that it requires to go to a neighbour's and learn, from a sight of the operation, that which, after all, no written directions would ever teach. To bud and graft, in all the various modes, form a much nicer and more complicated operation than that of making a shoe; and I defy any human being to describe adequately all the several acts in the making of a shoe, in less than two volumes, each larger than this. The season for taking off the cuttings for grafts, is any time between Christmas and March. Any time after the sap is completely in a quiescent state and before it be again in motion. When cut off they will keep several months. I cut some here in January last (1819.) They reached England in March; arid, I hear that they were growing well in June. A great deal has been said about the season for grafting, and Mr. MARSHALL tells the English, that it must not be done till the sap in the stock is just ready to flow freely. He has never seen an American Negro-man sitting by a hot six-plate stove, grafting apple-trees in the month of January, and then putting them away in his cave, to be brought out and planted in April! I have seen this; and my opinion is, that the work may be done at any time between October and May: nay, I am not sure, that it may not be done all the summer long. The cuttings too, may be taken off, and put on directly; and, the sooner the better; but, in the winter months, they will keep good off the tree for several months, 282. STOCKS must be of different ages and sizes in different cases; and even the propagation of the stocks themselves is not to be over-looked. Stocks are formed out of suckers, or raised from the seed; and the latter is by far the best; for suckers produce suckers, and do not grow to a handsome stem, or trunk. Crabs are generally the stocks for Apple-grafts, and Plums for Pears, Peaches, Nectarines, and Apricots. However, we shall speak of the sorts of Stocks, suitable to each sort of fruit-tree by and by: at present we have to speak of the raising of Stocks. If the stocks be to be of crabs or apples, the seeds of these should be collected in the fall when the fruit is ripe. They are generally got out by mashing the crabs, or apples. When the seeds are collected, put them immediately into fine earth; or sow them at once. It may not, however, be convenient to sow them at once; and, perhaps, the best way is to sow very early in the spring. If the stocks be to be of stone fruit, the stones, as of cherries, plumbs, peaches, and others, must be got when the fruit is ripe. The best way is to put them into fine earth, and keep them there till spring. The earth may he placed in a cellar; or put into a barrel; or, a little pit may be made in the ground, and it may be placed there. When the winter breaks up, dig a piece of ground deep and make it rich; make it very fine; form it into beds, three feet wide; draw drills across it at 8 inches distance; make them from two to three inches deep; put in the seeds pretty thick (for they cost little;) cover them completely; tread the earth down upon them; and then smooth the surface. When the plants come up, thin them to about 3 inches apart; and keep the ground between them perfectly clean during the summer. Hoe frequently; but not deep near the plants; for, we are speaking of trees here; and trees do not renew their roots quickly as a cabbage, or a turnip, does. These young trees should be kept, during the first summer, as moist as possible, without watering; and the way to keep them as moist as possible is to keep the ground perfectly clean, and to hoe it frequently. I cannot help observing here upon an observation of Mr. MARSHALL: "as to weeding," says he, "though seedling trees must not be smothered, yet some small weeds may be suffered to grow in summer, as they help to shade the plants and keep the ground cool." Mercy on this Gentleman's readers! Mr. Marshall had not read TULL; if he had, he never would have written this very erroneous sentence. It is the root of the weed that does the mischief. Let there be a rod of ground well set with even "small weeds," and another rod kept weeded. Let them adjoin each other. Go, after 15 or 20 days of dry weather; examine the two; and you will find the weedless ground moist and fresh, while the other is dry as dust to a foot deep. The root of the weed sucks up every particle of moisture. What pretty things they are, then, to keep seedling trees cool! — To proceed: these seedlings, if well managed, will be eight inches high, and some higher, at the end of the first summer. The next spring they should be taken up; or, this may be done in the fall. They should be planted in rows, four feet apart, to give room to turn about amongst them; and at two feet apart in the rows, if intended to be grafted or budded without being again removed. If intended to be again removed, before grafting or budding, they may be put at a foot apart. They should be kept clean by hoeing between them, and the ground between them should be dug in the fall, but not at any other season of the year. — The plants will grow fast or slowly according to the soil and management; and, he who knows how to bud or to graft, will know when the stock is arrived at the proper size for each purpose. — To speak of the kind of stocks, most suitable to the different kinds of fruit trees, is reserved till we come to speak of the trees themselves; but there are some remarks to be made here, which have a general application, relative to the kinds of stocks. — It is supposed by some persons, that the nature of the stock affects the nature of the fruit; that is to say, that the fruit growing on branches, proceeding from a bud, or a graft, partakes, more or less of the flavour of the fruit which would have grown on the stock, if the stock had been suffered to grow to a tree and to bear fruit. This is Mr. MARSHALL'S notion. But, how erroneous it is must be manifest to every one when he reflects, that the stock for the pear tree is frequently the white-thorn. Can a pear partake of the nature of the haw, which grows upon the thorn, and which is a stone-fruit too? If this notion were correct, there could be hardly a single apple-orchard in all England: for they graft upon crab-stocks; and, of course, all the apples, in the course of years, would become crabs. Apricots and Peaches are, in England, always put on plum-stocks; yet, after centuries of this practice, they do not become plumbs. If the fruit of the graft partake of the nature of the stock, why not the wood and leaves? Yet, is it not visible to all eyes, that neither ever does so partake? — This, then, like the carrying of the farina from the male to the female flower, is a mere whim, or dream. The bud, or graft, retains its own nature, wholly unchanged by the stock; and, all that is of consequence, as to the kind of stock, is, whether it be such as will last long, and supply the tree with a suitable quantity of wood. This is a matter of great importance; for, though peach will grow on peach, and apple on apple, the trees are not nearly so vigorous and durable as if the peach were put on the plum and the apple on the crab. In 1800, I sent several trees from England to Messrs. James and Thomas Paul, at Busleton, in Pennsylvania. There was a Nectarine amongst these. It is well known, that, in 1817, there had been so great a mortality in the peach orchards, that they had become almost wholly extinct. At Busleton there had been as great a mortality as in any other part. Yet I, that year, saw the Nectarine tree large, sound in every part, fine and flourishing. It is very well known, that the peach trees here are very short-lived. Six, seven, or eight years, seem to be the duration of their life. This Nectarine had stood seventeen years, and was likely to stand twice as long yet to come. It is now growing in the garden of the late Mr. James Paul, in Lower Dublin Township; and there any one may see it. — It is clear to me, therefore, that the short life of th peach-orchards is owing to the stock being peach. No small part of the peach-trees are raised from the stone. Nothing is more frequent than to see a farmer, or his wife, when he or she has eaten a good peach, go and make a little hole and put the stone in the ground, in order to have a peach tree of the same sort! Not considering, that the stone never, except by mere accident, produces fruit of the same quality as that within which it was contained, any more than the seed of a carnation produces flowers like those from which they proceeded. — The peaches in America are, when budded, put on peach-stocks; and this, I think, is the cause of their swift decay. They should be put on plum-stocks; for, to what other cause are we to ascribe the long life and vigorous state of the Nectarine at Mr. Paul's? The plum is a closer and harder wood than the peach. The peach-trees are destroyed by a worm, or, rather, a sort of maggot, that eats into the bark at the stem. The insects do not like the plum bark; and, besides, the plum is a more hardy and vigorous tree than the peach, and, observe, it is frequently, and most frequently, the feebleness, or sickliness, of the tree that creates the insects, and not the insects that create the feebleness and sickliness. There are thousands of peach trees in England and France that are fifty years old, and that are still in vigorous fruitfulness. There is a good deal in climate, to be sure; but, I am convinced, that there is a great deal in the stock. — Before I quit the subject of stocks, let me beg the reader never, if he can avoid it, to make use of suckers, particularly for an apple or pear-orchard, which almost necessarily is to become pasture. Stocks formed out of suckers produce suckers; and, if the ground remain in grass for a few years, there, will arise a young wood all over the ground; and this wood, if not torn up by the plough, will, in a short time, destroy the trees, and will in still less time, deprive them of their fruitfulness. Besides this, suckers, being originally excrescences, and unnaturally vigorous, make wood too fast, make too much wood; and, where this is the case, the fruit is scanty in quantity. "Haste makes waste" in most cases; but, perhaps, in nothing so much as in the use of suckers as stocks. By waiting a year longer and bestowing a little care, you obtain seedling stocks; and, really, if a man has not the trifling portion of patience and industry that is here required, he is unworthy of the good fruit and the abundant crops, which with proper management, are sure, in this country, to be the reward of his pains. — Look at England, in the spring! There you see fruit trees of all sorts covered with bloom; and from all of it there sometimes comes, at last, not a single fruit. Here, is this favoured country, to count the blossoms is to count the fruit! The way to show our gratitude to God for such a blessing, is, to act well our part in turning the blessing to the best account. _____________________________ PLANTING. 283. I am not to speak here of the situation for planting, of the aspect, of the nature of the soil, of the preparation of the soil; for these have all been described in CHAPTER I, Paragraph 20, save and except, that, for trees, the ground should be prepared as directed for Asparagus, which see in its Alphabetical place, in Chapter IV. 284. Before the reader proceed further, he should read very attentively what is said of transplanting generally, in Chapter III, Paragraph 109 and onwards. He will there perceive the absolute necessity of the ground, to be planted in, being made perfectly fine, and that no clods, great or small, ought to be tumbled in about the roots. This is so capital a point, that I must request the reader to pay particular attention to it. To remove a tree, though young, is an operation that puts the vegetative faculties to a severe test; and, therefore, every thing should be done to render the shock as little injurious as possible. 285. The tree to be planted should be as young as circumstances will allow. The season is just when the leaves become yellow, or, as early as possible in the spring. The ground being prepared, and the tree taken up, prune the roots with a sharp knife so as to leave none more than about a foot long; and, if any have been torn off nearer to the stem, prune the part, so that no bruizes or ragged parts remain. Cut off all the fibres close to the roots; for, they never live, and they mould, and do great injury. If cut off, their place is supplied by other fibres more quickly, Dig the hole to plant in three times as wide, and six inches deeper, than the roots actually need as mere room. And now, besides the fine earth generally, have some good mould sifted. Lay some of this six inches deep at the bottom of the hole. Place the roots upon this in their natural order, and hold the tree perfectly upright, while you put more sifted earth on the roots. Sway the tree backward and forward a little, and give it a gentle lift and shake, so that the fine earth may find its way amongst the roots and leave not the smallest cavity. Every root should be closely touched by the earth in every part. When you have covered all the roots with the sifted earth, and have seen that your tree stands just as high with regard to the level of the ground as it did in the place where it before stood, allowing about 3 inches for sinking, fill up the rest of the hole with the common earth of the plat, and when you have about half filled it, tread the earth that you put in, but not very hard. Put on the rest of the earth, and leave the surface perfectly smooth. Do not water by any means. Water, poured on, in this case, sinks rapidly down, and makes cavities amongst the roots. Lets in air. Mould and canker follow; and great injury is done. 286. If the tree be planted in the fall, as soon as the leaf begins to be yellow; that is to say, in October early, it will have struck out new roots to the length of some inches before the winter sets in. And this is certainly the best time for doing the business. But, mind, the roots should be out of ground as short a time as possible; and should by no means be permitted to get dry, if you can avoid it; for, though some trees will live after having been a long while out of ground, the shorter the time out of ground the sooner the roots strike; and, if the roots should get dry before planting, they ought to be soaked in water, rain or pond, for half a day before the tree be planted. 287. If the tree be for an orchard, it must be five or six feet high, unless cattle are to be kept out for two or three years. And, in this case, the head of the tree must be pruned short, to prevent it from swaying about from the force of the wind. Even when pruned, it will be exposed to be loosened by this cause, and must be kept steady by a stake; but, it must not be fastened to a stake, until rain has come to settle the ground; for, such fastening would prevent it from sinking with the earth. The earth would sink from it, and leave cavities about the roots. 288. When the trees are short, they will require no stakes. They may be planted the second year after budding, and the first after grafting; and these are the best times. If planted in the fall, the tree should be shortened very early in the spring, and in such a way as to answer the ends to be pointed out more particularly when we come to speak of pruning. 289. If you plant in the spring, it should be as early as the ground will bear moving; only, bear in mind, that the ground must always be dry at top when you plant. In this case, the new roots will strike out almost immediately; and as soon as the buds begin to swell, shorten the head of the tree. After a spring-planting, it may be necessary to guard against drought; and the best protection is the laying of small stones of any sort round the tree, so as to cover the area of a circle of three feet in diameter, of which circle the stem of the tree is the centre. This will keep the ground cooler than any thing else that you can put upon it. 290. As to the distances, at which trees ought to be planted, that must depend on the sort of tree, and on other circumstances. It will be seen by looking at the plan of the garden (Plate 1,) that I make provision for 70 trees, and for a row of grape vines extending the length of two of the plats. The trees will have a space of 14 feet square each. But, in orchards, the distances for apples and pears must be much greater otherwise the trees will soon run their branches into, and injure each other. _____________________________CULTIVATION. 291. The Cultivation of fruit trees d vides itself into two distinct parts; the management of the tree itself, which consists of pruning and tying; and the management of the ground where the trees grow, which consists of digging, hoeing, and manuring. The management of the tree itself differs with the sort of tree; and, therefore, I shall treat of the management of each sort under its own particular name. But the management of the ground where trees grow is the same in the case of all the larger trees; and, for that reason, I shall here give directions concerning it. 292. In the first place, the ground is always to be kept clear of weeds; for, whatever they take is just so much taken from the fruit, either in quantity, or in quality, or in both. It is true, that very fine orchards have grass covering all the ground beneath the trees; but, these orchards would be still finer if the ground were kept clear from all plants whatever except the trees. Such a piece of ground is, at once, an Orchard and a Pasture: what is lost one way is, probably, gained the other. But, if we come to fine and choice fruits, there can be nothing that can grow beneath to balance against the injury done to the trees. 293. The roots of trees go deep; but, the principal part of their nourishment comes from the topsoil. The ground should be loose to a good depth, which is the certain cause of constant moisture; but trees draw downwards as well as upwards, and draw more nourishment in the former than in the latter direction. Vineyards, as TULL observes, must always be tilled, in some way or other; or they will produce nothing of value. He adds, that Mr. EVELYN says, that "when the soil, wherein fruit-trees are planted, is constantly kept in tillage, they grow up to an Orchard in half the time, they would do, if the soil were not tilled." Therefore, tillage is useful; but, it were better, that there were tillage without under crops; for these crops take away a great part of the strength that the manure and tillage bring. 294. Now, then, as to the trees in my garden; they are to be choice peaches, nectarines, apricots, plums, cherries, and grape vines, with a very few apples and pears. The sorts will be mentioned hereafter in the Alphabetical list; but, the tillage for all except the grape vines, is the same; and the nature of that exception will be particularly stated under the name of grape. 295. It was observed before, that the ground is always to be kept clear of weeds. From the spring to the fall frequent hoeing all the ground over, not only to keep away weeds but to keep the ground moist in hot and dry weather, taking care never to hoe but when the ground is dry at top. This hoeing should not go deeper than four or five inches; for, there is a great difference between trees and herbaceous plants as to the renewal of their roots respectively. Cut off the lateral root? of a cabbage, or a turnip, of a wheat or a rye or an Indian-corn plant, and new roots, from the parts that remain, come out in 12 hours, and the operation, by multiplying the mouths of the feeders of the plant, gives it additional force. But, the roots of a tree consist of wood, more or less hard; they do not quickly renew themselves: they are of a permanent nature: and they must not be much mutilated during the time that the sap is in the flow. 296. Therefore, the ploughing between trees or the digging between trees ought to take place only in the fall, which gives time for a renewal, or new supply, of roots before the sap be again in motion. For this reason, if crops be grown under trees in orchards, they should be of wheat, rye, winter-barley, or of something that does not demand a ploughing of the ground in the spring. In the garden, dig the ground well and clean, with a fork, late in November. Go close to the stems of the trees; but do not bruise the large roots. Clean and clear all well close round the stem. Make the ground smooth just there. Ascertain whether there be insects there of any sort. And, if there be, take care to destroy them. Pull, or scrape, off all rough bark at the bottom of the stem. If you even peel off the outside bark a foot or two up, in case there be insects, it will be the better. Wash the stems with water, in which tobacco has been soaked; and do this, whether you find insects or not. Put the tobacco into hot water, and let it soak 24 hours, before you use the water. This will destroy, or drive away, all insects. 297. But, though, for the purpose of removing all harbour for insects, you make the ground smooth just round the stem of the tree, let the rest of the ground lay as rough as you can; for the rougher it lies the more will it be broken by the frost, which is a great enricher of all land. When the spring comes, and the ground is dry at the top, give the whole of the ground a good deep hoeing, which will make it level and smooth enough. Then go on again hoeing throughout the summer, and watching well all attempts of insects on the stems and bark of the trees. 298. Diseases of trees are various in their kind; but, nine times out of ten they proceed from the root. Insects are much more frequently an effect than a cause. If the disease proceed from blight, there is no prevention, except that which is suggested by the fact, that feeble and sickly trees are frequently blighted when healthy ones are not; but, when the insects come, they add greatly to the evil They are generally produced by the disease, as maggots are by putrefaction. The ants are the only active insect for which there is not a cure; and I know of no means of destroying them, but finding out their nests, and pouring boiling water on them. A line dipped in tar tied round the stem will keep them from climbing the tree: but they are still alive. As to the diminutive creatures that appear as specks in the bark; the best, and perhaps, the only remedy against the species of disease of which they are the symptoms, consists of good plants, good planting and good tillage. When orchards are seized with diseases that pervade the whole of the trees, or nearly the whole, the best way is to cut them down: they are more plague than profit, and, as long as they exist, they are a source of nothing but constantly-returning disappointment and mortification. However, as there are persons who have a delight in quackery, who are never so happy as when they have some specific to apply, and to whom rosy cheeks and ruby lips are almost an eye-sore, it is, perhaps, fortunate, that the vegetable world presents them with patients; and thus, even in the cotton-blight or canker, we see an evil, which we may be led to hope is not altogether unaccompanied with good. LIST OF FRUITS. 299. Having, in the former parts of this CHAPTER, treated of the propagation, planting, and cultivation of all fruit trees (the grape vine only excepted) it would remain for me merely to give a List of the several fruits; to speak of the different sorts of each; and of the mode of preserving them; but the stocks and pruning vary, in some cases; and, therefore, as I go along, I shall have to speak of them. Before, however, I enter on this Alphabetical List, let me observe, that only a part of the fruits mentioned in it are proposed to be raised in the garden; and that the 70 trees, shown in the Plate I, are intended to mark the paces, and, in some degree, the form, of 6 Apple trees, 6 Apricots, 6 Cherries, 6 Nectarines, 30 Peaches, 6 Pears, and 10 Plums; and, that the trelises, on the Southern sides of Plats, No. 8 and 9, are intended to mark the places for 4 Grape-Vines, there being another Plate to explain more fully the object and dimensions of this trelis work. 300. APPLE. — Apples are usually grafted on crab-stocks (See Paragraph 281;) but, when you do not want the trees to grow tall and large, it is better to raise stocks from the seed of some Apple not much given to produce large wood. Perhaps the Fall-Pippin seed may be as good as any. When you have planted the tree, as directed in Paragraphs 283 to 289, and when the time comes for shortening the head, cut it off so as to leave only five or six joints or buds. These will send out shoots, which will become limbs. The tree will be what they call, in England, a dwarf standard; and, of this description are to be all the 70 trees in the garden. — As to pruning, see PEACH; for, the pruning of all these dwarf standards is nearly the same. The sorts of Apples are numerous, and every body knows, pretty well, which are the best. In my garden I should only have six apple trees; and, therefore, they should be of the finest for the season at which they are eaten. The earliest apple is the Junating, the next the Summer Pearmain. Besides these I would have a Doctor-apple, a Fall-Pippin, a Newtown Pippin and a Greening. The quantity would not be very large that six trees would produce; yet it would be considerable, and the quality would be exquisitely fine. I would not suffer too great a number of fruit to remain on the tree; and, I would be bound to have the three last-named sorts weighing, on an average, 12 ounces I have seen a Fall-Pippin that weighed a pound. — To preserve apples, in their whole state, observe this, that frost does not much injure them, provided they be kept in total darkness during the frost and until they be used, and provided they be perfectly dry when put away. If put together in large parcels, and kept from the frost, they heat, and then they rot; and, those of them that happen not to rot, lose their flavour, become vapid, and are, indeed, good for little. This is the case with the Newtown Pippins that are sent to England, which are half lost by rot, while the remainder are poor tasteless stuff, very little better than the English apples, the far greater part of which are either sour or mawkish. The apples thus sent, have every possible disadvantage. They are gathered carelessly; tossed into baskets and tumbled into barrels at once, and without any packing stuff between them; the barrels are flung into and out of wagons; they are rolled along upon pavements; they are put in the hold, or between the decks, of the ship: and, is it any wonder, that a barrel of pomace, instead of apples, arrive at Liverpool or London? If, instead of this careless work, the apples were gathered (a week before ripe); not bruised at all in the gathering; laid in the sun, on boards or cloths, three days, to let the watery particles evaporate a little: put into barrels with fine-cut straw-chaff, in such a way as that no apple touched another; carefully carried to the ship and put on board, and as carefully landed; and if this were the mode, one barrel, though it would contain only half the quantity, would sell for as much as, upon an average, taking in loss by total destruction, twenty barrels sell for now. On the deck is the best part of the ship for apples; but, if managed as I have directed, between decks would do very well. — In the keeping of apples for market, or for home-use, the same precautions ought to be observed as to gathering and laying out to dry; and, perhaps, to pack in the same way also is the best mode that can be discovered. Dried Apples is an article of great and general use. Every body knows, that the apples are peeled, cut into about eight pieces, the-core taken out and the pieces put in the sun till they become dry and tough. They are then put by in bags, or boxes, in a dry place. But, the flesh of the apple does not change its nature in the drying; and, therefore, the finest, and not the coarsest, apples should have all this trouble bestowed upon them. 301. APRICOT. — This is a very delightful fruit. It comes earlier than the peach: and some like it better. It is a hardier tree, bears as well as the peach, and the green fruit, when the size of a hickory-nut, makes a very good tart. When ripe, or nearly ripe, it makes a better pie than the peach; and the tree, when well raised, planted, and cultivated, will last a century. — Apricots are budded or grafted upon plum stocks, or upon stocks raised from Apricot-stones. They do not bear so soon as the peach by one year. For the pruning of them, see PEACH. — There are many sorts of Apricots, some come earlier, some are larger, and some finer than others. It may be sufficient to name the Brussels, the Moore-Park, and the Turkey. The first carries most fruit as to number; but, the others are larger and of finer flavour. Perhaps two trees ol each of these sorts would be the most judicious selection. I have heard, that the Apricot does not do in this country! That is to say, I suppose, it will not do of its own accord, like a peach, by having the stone flung upon the ground, which it certainly will not; and it is very much to be commended for refusing to do in this way. But, properly managed, I know it will do, for I never tasted finer Apricots than I have in America; and, indeed, who can believe that it will not do in a country, where there are no blights of fruit trees worth speaking of, and where melons ripen to such perfection in the natural ground and almost without care? 302. BARBERRY. — This fruit is well known. The tree, or shrub, on which it grows, is raised from the seed, or from suckers, or layers. Its place ought to be in the South Border; for, the hot sun is rather against its fruit growing large. 303. CHERRY. — Cherries are budded or grafted upon stocks raised from cherry-stones of any sort. If yon want the tree tall and large, the stock should come from the small black cherry tree that grows wild in the woods. If you want it dwarf, sow the stones of a morello or a May-duke. The sorts of cherries are very numerous; but, the six trees for my garden should be, a May-cherry, a May-duke, a Hack-heart, a white-heart, and two bigeroons. The four former are well known in America, but I never saw but two trees of the last, and those I sent from England to Bustleton, in Pennsylvania, in the year 1800. They are now growing there, in the gardens of the two Messrs. Paul's. Cuttings from them have been carried and used as grafts all round the country. During the few days that I was at Mr. James Paul's, in 1817, several persons came for grafts; so that these trees must be pretty famous. The fruit is large, thin skinned, small stone, and fine colour and flavour, and the tree grows freely and in beautiful form. — For Pruning, see PEACH. — To preserve cherries, gather them without bruizing; take off the tails; lay them in the sun on dry deal hoards; when quite dry put them by in bags in a dry place. They form a variety in the tart-making way. 304. CHESTNUT. — This is an inhabitant of the woods; and, as to its fruit, I have only to say, that the American is as much better than the Spanish as the tree is a finer tree. — To preserve chestnuts, so as to have them to sow in the spring, or to tat through the winter, you must put them into a box, or barrel, mixed with, and covered over by, fine dry sand. If there be maggots in any of the chestnuts, they will work up through the sand, to get to air; and, thus, you have your chestnuts sweet and sound and fresh. To know whether chestnuts will grow, toss them into water. If they swim, they will not grow. 305. CRANBERRY. — This is one of the best fruits in the world. All tarts sink out of sight in point of merit, when compared with that made of the American Cranberry. There is a little dark red thing, about as big as a large pea, sent to England from the North of Europe, and is called a Cranberry; but, it does not resemble the American in taste any more than in bulk. — It is well known that this valuable fruit is, in many parts of this country, spread over the low lands in great profusion; and that the mere gathering of it is all that bountiful nature requires at our hands. — This fruit is preserved all the year, by stewing and putting into jars, and when taken thence is better than currant jelly. The fruit, in its whole state, laid in a heap, in a dry room, will keep sound and perfectly good for six months. It will freeze and thaw and freeze and thaw again without receiving any injury. It may, if you choose, be kept in water all the while, without any injury. I received a barrel in England, mixed with water, as good and as fresh as I ever tasted at New York or Philadelphia. 306. CURRANT. — There are red, white and black, all well known. Some persons like one best, and some another. The propagation and cultivation of all the sorts are the same. The currant tree is propagated from cuttings; and the cuttings are treated as has been seen in Paragraph 275. When the tree has stood two years in the Nursery, plant it where it is to stand; and take care that it has only one stem. Let no limbs come out to grow nearer than six inches of the ground. Prune the tree every year. Keep it thin of wood. Keep the middle open and the limbs extended; and when these get to about three feet in length, cut off, every winter, all the last year's shoots. If you do not attend to this, the tree will be nothing but a great bunch of twigs, and you will have very little fruit. Cultivate and manure the ground as for other fruit trees. See Paragraphs 289 to 296. In this country the currant requires shade in summer. If exposed to the full sun, the fruit is apt to become too sour. Plant it, therefore, in the South Border. 307. FIG. — There are several sorts of Figs, but all would ripen in this country. The only difficulty must be to protect the trees in winter, which can hardly be done without covering pretty closely. Figs are raised either from cuttings or layers which are treated as other cuttings and layers are. See Paragraphs 275 and 277. The fig is a mawkish thing at best; and, amongst such quantities of fine fruit as this country produces, it can, from mere curiosity only, be thought worth raising at all, and especially at great trouble. 308. FILBERD. — This is a sort of Nut, oblong in shape, very thin in the shell, and in flavour as much superior to the common nut as a Watermelon is to a pumpkin. The American nut tree is a dwarf shrub. The Filberd is a tall one, and will, under favourable circumstances, reach the height of thirty feet. I never saw any Filberd trees in this country, except those that I sent from England in 1800. They are six in number, and they are now growing in the garden of the late Mr. JAMES PAUL, of Lower Dublin Township, in Philadelphia county. I saw them in 1817, when they were, I should suppose, about 20 feet high. They had always borne, I was told, very large quantities, never failing. Perhaps five or six bushels a year, measured in the husk, a produce very seldom witnessed in England; so that, there is no doubt that the climate is extremely favourable to them. Indeed to what, that is good for man, is it not favourable? — The Filberd is propagated from layers, or from suckers, of which latter it sends forth great abundance. The layers are treated like other layers, (See Paragraph 276,) and they very soon become trees. The suckers are also treated like other suckers. (See Paragraph 277;) but, layers are preferable, for the reasons before stated. — This tree cannot be propagated from seed to bear Filberds. The seed, if sown, will produce trees; but, those trees will bear poor thick-shelled nuts, except it be by mere accident. It is useful to know how to preserve the fruit; for it is very pleasant to have it all the winter long. Always let the filberds hang on the tree till quite ripe, and that is ascertained by their coming out of the husk without any effort. They are then brown, and the butt ends of them white. Lay them in the sun for a day to dry; then put them in a box, or jar, or barrel, with very fine dry sand. Four times as much sand as filberds, and put them in any dry place. Here they will keep well till April or May; and, perhaps, longer. This is better a great deal than putting them, as they do in England, into jars, and the jars into a cellar; for if they do not mould in that situation, they lose much of their sweetness in a few months. — The burning sun is apt to scorch up the leaves of the Filberd tree. I would, therefore, plant a row of them as near as possible to the South fence. Ten trees at eight feet apart might be enough. — The Filberd will do very well under the shade of lofty trees, if those trees do not stand too thick. And it is by no means an ugly shrub, while the wood of it is, as well as the nut wood, which is, in England, called hazel, and is a very good wood. In the oak-woods there, hazel is very frequently the underwood; and it makes small hoops, and is applied to various other purposes. — I cannot dismiss this article without exhorting the American farmer to provide himself with some of this sort of tree, which, when small, is easily conveyed to any distance in winter, and got ready to plant out in the spring. Those that are growing at Mr. PAUL'S were dug up, in England, in January, shipped to New York, carried on the top of the stage, in the dead of winter to Busleton, kept in a cellar till spring and then planted out. These were the first trees of the kind, as far as I have been able to learn, that ever found their way to this country. I hear that Mr. STEPHEN GERRARD takes to himself the act of first introduction, from France. But, I must deny him this. He, I am told, brought his trees several years later than I sent mine. 309. GOOSEBERRY. — Various are the sorts, and no one that is not good. The shrub is propagated precisely like that of the currant. I cannot tell the cause that it is so little cultivated in America. I should think (though I am by no means sure of the fact) that it would do very well under the shade of a South Fence. However, as far as the fruit is useful in its green state, for tarts, the Rhubarb supplies its place very well. The fruit is excellent when well raised. They have gooseberries in England nearly as large as pigeon's eggs, and the crops that the trees bear are prodigious.

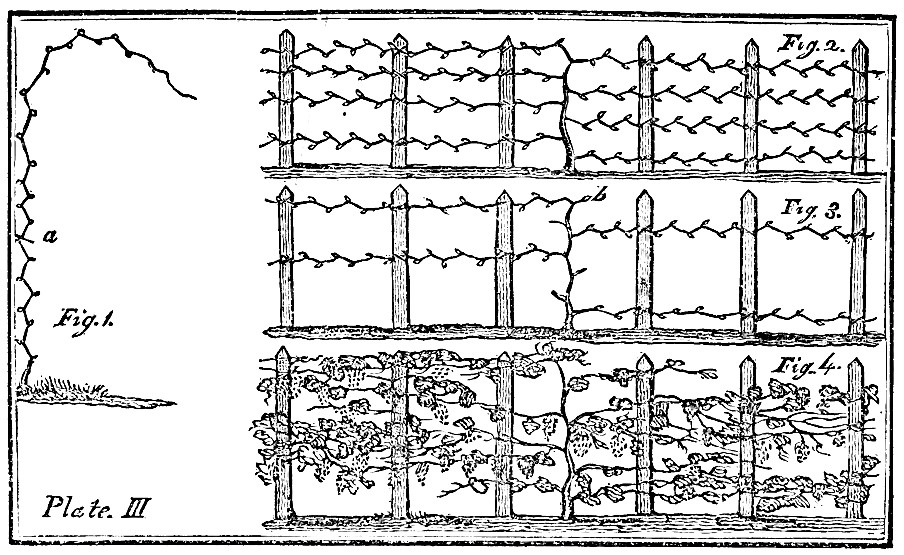

310. GRAPE. — This is a very important article; and, before I proceed to treat of the culture of the grape-vine, I must notice the astonishing circumstance, that that culture should be almost wholly unknown in this country of fine sun. I have asked the reason of this, seeing that the fruit is so good, the crop so certain, and culture so easy. The only answer that I have received is, that the rose-bug destroys the fruit. Now, this I know, that I had a grape vine in my court-yard at Philadelphia; that it bore nothing the first year; that I made an arched trelis for it to run over; and that I had hundreds of pounds of fine grapes hanging down in large bunches. Yes, I am told, but this was in a city; and amongst houses, and there the grapes do very well. Then, 1799, I saw, at Spring Mills, on the banks of the Schuylkill, in Pennsylvania, the Vineyard of Mr. Le Gau, which covered about two acres of ground, and the vines of which were loaded with the grapes of, at least, twenty different sorts. The vineyard was on the side of a little hill; on the top of the hill was a corn-field, and in the front of it, across a little valley, and on the side of another little hill, was a wood of lofty trees; the country in general, being very much covered with woods. Mr. LA GAU made wine from this Vineyard. The vines are planted at about four feet apart, grew upright, and were tied to sticks about five feet high, after the manner of some, at least, of the vineyards of France. Now, are not these facts alone decisive in the negative of the proposition, that there is a generally prevalent obstacle to the growing of grapes in this country? Mr. HULME, in his Journal to the West (See my Year's Residence, Paragraph 892,) gives an account of the Vineyards and of the wine made, at VEVAY, on the OHIO. He says, that, that year, about five thousand gallons of wine were made; and, he observes, what more can be wanted for the grape-vine, than rich land and hot sun. Besides, is not the grape-vine a native here? There are many different sorts of grapes, that grow in the woods, climb the trees, cover some of them over, and bear and ripen their fruit. How often do we meet with a vine, in the autumn, with Grapes, called chicken grapes, hanging on it from every bough of an oak or some other timber-tree! This grape resembles, as nearly as possible, what is, in England, called the Black Cluster; and, unquestionably, only wants cultivation to give it as good a flavour. Does the Rose bug prevent these vines from bearing, or from ripening their fruit? Taking it for granted, then, that this obstacle is imaginary, rather than real, I shall now proceed to speak of the propagation and cultivation of the grape-vine in the open ground of a garden, and, in doing this, I shall have frequently to refer to PLATE III. — The grape-vine is raised from cuttings, or from layers. As to the first, you cut off, as early as the ground is open in the spring, a piece of the last year's wood; that is to say, a piece of a shoot, which grew during the last summer. This cutting should, if convenient, have an inch or two of the former year's wood at the bottom of it; hut, this is by no means absolutely necessary. The cutting should have four or five buds or joints. Make the ground rich, move it deep, and make it fine. Then put in the cutting with a setting-stick, leaving only two buds, or joints, above ground; fasten the cutting well in the ground; and, then, as to keeping it cool and moist, see cuttings, in Paragraph 275. — Layers from grape-vines are obtained with great ease. You have only to lay a shoot, or limb, however young or old, upon the ground, and cover any part of it with earth, it will strike out roots the first summer, and will become a vine, to be carried and planted in any. other place. But, observe, vines do not transplant well. For this reason, both cuttings and layers, if intended to be removed, are usually set, or layed, in flower-pots, out of which they are turned, with the ball of earth along with them, into the earth where they are intended to grow and produce their fruit. I have now to speak more particularly of the vines of my garden. PLATE I. represents, or, at least, I mean it to represent, on the south side of the Plats No. 8 and No. 9, two trelis works for vines. These are to be five feet high, and are to consist of two rows of little upright bars two inches and a half by two inches, put two feet into the ground, and made of Locust, and then they will, as you well know, lasts for ever, with-out paint and without any kind of trouble. — Now, then, bear in mind, that each of these Plats, is, from East to West, 70 feet long, Each will, therefore, take four vines, allowing to each vine an extent of 16 feet, and something more for overrunning branches. Look, now, at PLATE III, which exhibits, in all its dimensions, the cutting become a plant, FIG. 1. The first year of its being a vine after the leaves are off and before pruning, FIG. 2. The same year's vine pruned in winter, FIG. 3. The vine, in the next summer, with shoots, leaves, and grapes, FIG. 4. Having measured your distances, put in a cutting at each place where there is to be a vine. You are to leave two joints or buds out of ground. From these will come two shoots perhaps; and, if two come, rub off the top one and leave the bottom one, and, in winter, cut off the bit of dead wood which will, in this case, stand above the bottom shoot. Choose, however, the upper one to remain, if the lower one be very weak. Or, a better way is, to put in two or three cuttings within an inch or two of each other, leaving only one bud to each out of ground, and taking away, in the fall, the cuttings that send up the weakest shoots. The object is to get one good shoot coming out as near to the ground as possible. — This shoot you tie to an upright stick, letting it grow its full length. When winter comes, cut this shoot down to the bud nearest to the ground. — The next year another, and a much stronger shoot will come out; and, when the leaves are off, in the fall, this shoot will be eight or ten feet long, having been tied to a stake as it rose, and will present what is described in FIG. 1, PLATE III. You must make your trelis; that is, put in your upright Locust-bars to tie the next summer's shoots to. You will want (See FIG. 2.) eight shoots to come out to run horizontally, to be tied to these bars. You must now, then, in winter, cut off your vine, leaving eight buds, or joints. You see there is a mark for this cut, at a, fig. 1. During summer 8 shoots will come, and as they proceed on, they must be tied with matting, or something soft, to the bars. The whole vine, both ways included, is supposed to go 16 feet; but, if your tillage be good, it will go much further, and then the ends must be cut off in winter. — Now, then, winter presents you your vine as in fig. 2; and now you must prune, which is the all-important part of the business. — Observe, and bear in mind, that little or no fruit ever comes on a grape-vine, except on young shoots that come out of wood of the last year. All the four last year's shoots that you find in fig. 2, would send out bearers; but, if you suffer that, you will have a great parcel of small wood, and little or no fruit next year. Therefore, cut off 4 of the last year's shoots, as at b. (Fig. 3.) leaving only one bud. The four other shoots will send out a shoot from every one of their buds, and, if the vine be strong, there will be two bunches of grapes on each of these young shoots; and, as the last year's shoots are supposed to be each 8 feet long, and as there generally is a bud at, or about, every half foot, every last year's shoot will produce 32 bunches of grapes; every vine 128 bunches; and the 8 vines 12; and, possibly, nay, probably, so many pounds of grapes! Is this incredible? Take, then, this well known fact, that there is a grape vine, a single vine, with only one stem, in the King of England's Gardens at his palace of Hampton Court, which has, for, perhaps, half a century, produced on an average, annually, a ton of grapes; that is to say, 2,240 pounds Avoirdupois weight. That vine covers a space of about 40 feet in length and 20 in breadth. And your two trelises, being, together, 128 feet long, and 4 deep, would form a space of more than half the dimensions of the vine of Hampton Court. However, suppose you have only a fifth part of what you might have, a hundred bunches of grapes are worth a great deal more than the annual trouble, which is, indeed, very little. Fig. 4 shows a vine in summer. You see the four shoots bearing, and four other shoots coming on for the next year, from the butts left at the winter pruning, as at b. These four latter you are to tie to the bars as they advance on during the summer. — When winter comes again, you are to cut off the four shoots that sent out the bearers during the summer, and leave the four that grew out of the butts. Cut the four old shoots that have borne, so as to leave but one bud at the butt. And they will then be sending out wood, while the other four will be sending out fruit. And thus you go on year after year for your life; for, as to the vine, it will, if well treated, outlive you and your children to the third and even thirtieth generation. I think they say, that the vine at Hampton Court was planted in the reign of King William. — During the summer there are two things to be observed, as to pruning. Each of the last year's shoots has 32 buds, and, of course, it sends out 32 shoots with the grapes on them, for the grapes come out of the 2 first fair buds of these shoots. So that here would be an enormous quantity of wood, if it were all left till the end of summer. But, this must not be. When the grapes get as big as peas, cut off the green shoots that bear them, at two buds distance from the fruit. This is necessary in order to clear the vine of confusion of branches, and also to keep the sap back for the supply of the fruit. These new shoots, that have the bunches on, must be kept tied to the trelis, or else the wind would tear them off. The other thing is, to take care to keep nicely tied to the bars the shoots that are to send forth bearers the next year; and, if you observe any little side-shoots coming out of them to crop these off as soon as they appear, leaving nothing but the clear, clean shoot. It may be remarked, that the butt, as at b, when it is cut off the next time, will be longer by a bud. That will be so; but, by the third year the vine will be so strong that you may safely cut the shoots back to within six inches of the main trunk, leaving the new shoots to come out of it where they will; taking care to let but one grow for the summer. If shoots start out of the main trunk irregularly, rub them off as soon as they appear, and never suffer your vine to have any more than its regular number of shoots. As to cultivation of the ground, the ground should not only be deeply dug in the fall, but, with a fork, two or three times during the summer. They plough between them in Languedoc, as we do between the Indian Corn. The ground should be manured every fall, with good rich manure. Blood of any kind is excellent for vines. But, in a word, the tillage and the manuring cannot be too good. All that now remains is to speak of the sorts of grapes. The climate of this country will ripen any sort of grape. But, it may be as well to have some that come early. The Black July grape, as it is called in England, or, as it is called in France, the Noir Hatif, is the earliest of all. I would have this for one of my eight vines; and, for the other seven I would have, the Chasselas; the Burgundy; the Black Muscadine; the Black Frontinac; the Red Frontinac; the White Sweet Water; and the Black Hamburgh, which is the sort of the Hampton-Court Vine. — In cases where grapes are to be grown against houses, or to be trained over bowers, the principle is the same, though the form may differ. If against the side of a house, the main stem of the vine might, by degrees, be made to go, I dare say, a hundred feet high. Suppose 40 feet. In that case, it would be forty instead of four; but the side shoots, or alternate bearing limbs, would still come out in the same manner. The stem, or side limbs, may, with the greatest ease, be made to accommodate themselves to windows, or to any interruptions of smoothness on the surface. If the side of the house, or place, be not very high, not more than 15 or 20 feet; the best way is to plant the vine in the middle of your space, and, instead of training an upright stem, take the two lowest shoots and lead them along, one from each side of the plant, to become stems, to lie along within six inches or a foot of the ground. These will, of course, send out shoots, which you will train upright against the building, and which you will cut out alternately, as directed in the other case. 311. HUCKLEBERRY. — It is well known that it grows wild in great abundance, in many parts, and especially in Long Island, where it gives rise to a holiday, called Huckleberry Monday. It is a very good fruit for tarts mixed with Currants; and by no means bad to eat in its raw state. 312 MADEIRA NUT. — See Walnut. 313. MEDLAR. — A very poor thing indeed. The Medlar is propagated by grafting on crab-stocks, or pear-stocks. It is, at any rate, especially in this country, a thing not worthy of a place in a garden. At best, it is only one degree better than a rotten apple. 314. MELON. — See Melon in Chapter IV. 315. MULBERRY. — This tree is raised from cuttings or from layers. See Paragraphs 275 and 377. The White-Mulberry, which is the finest, and which the Silk worm feeds on, grows wild, and bears well, at two miles from the spot where I am now writing. 316. NECTARINE. — As to propagation, planting and cultivation, the Nectarine is, in all respects, the same as the peach, which, therefore, see. It is certainly a finer fruit, especially the Violet Nectarine; but, it is not grown, or, but very little, in America. I cannot believe, that there is any insurmountable obstacle in the way. It is grown in England very well. The White French would certainly do here; and it is the most beautiful of fruit, and a greater bearer, though not so fine in flavour, as the Violet. The Newington, the Roman are by no means so good. I would have in the Garden three trees of each of the two former. 317. NUT. — Grows wild. Not worthy of a place in the Garden. Is propagated, and the fruit preserved, like Filberd, which see.

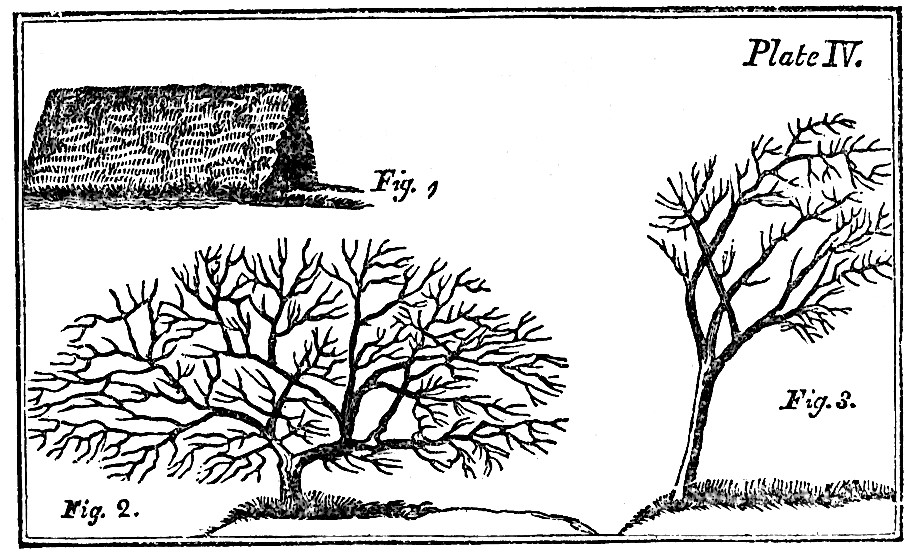

318. PEACH. — The peach being the principal tree for the garden, I shall, under this head, give directions for pruning and forming the tree. — Peaches are propagated by budding. The stock should be of plum, for the reasons given in Paragraph 281. — The tree is to be planted, agreeably to the directions in Paragraphs 282 to 288. And now for the pruning and forming the tree. Look at PLATE IV. fig. 2, and fig. 3. The first is a peach tree such as I would have it at four or five years, old; the last is a peach tree such as we generally see at that age. The practice is to plant the tree, and to let it grow in its own way. The consequence is, that, in a few years, it runs up to a long naked stem with two or three long naked limbs, having some little weak boughs at the tops, and, the tree being top-heavy, is, nineteen times out of twenty, leaning on one side; and it presents, altogether, a figure by no means handsome in itself or creditable to the owner. — This is fig. 3. — Now, to have fig. 2, the following is the way. — The tree should, in the first place, be budded very near to the ground. After it be planted, cut it down to within a foot and a half of the ground, and always cut sloping close to a bud. In this foot and a half, there will be many buds, and they will, the first summer, send out many shoots. Now, when shoots begin to appear, rub them all off but three, leave the top one, and one on each side, at suitable distances lower down. These will, in time become limbs. The next year, top the upright shoot (that came out of the top bud) again, so as to bring out other horizontal limbs, pointing in a different direction from those that came out the last year. Thus the tree will get a spread. After this, you must keep down the aspiring shoots; and, every winter, cut out some of the weak wood, that the tree may not be over-burdened with wood. If, in time, the tree be getting thin of bearing wood towards the trunk, cut some of the limbs back, and they will then send out many shoots, and fill up the naked places. The lowest limb of the tree, should come out of the trunk at not more than 9 or 10 inches from the ground. The greater part of the tree will be within the reach of a man from the ground, and a short step-ladder reaches the rest. — By this management the tree is always in a state of full bearing. Always young. To talk of a tree's being worn out is nonsense. But, without pruning, it will soon wear out. It is the pruning that makes it always young. In the "Ecole du Jar din Potager," by Monsieur DE COMBLES, there is an account of peach trees in full bearing at fifty years old. And, little do people here imagine to what a distance a peach tree will, if properly managed, extend. Mr. DE COMBLES speaks of numerous peach trees extending to more than fifty feet in length on the trelis, and twelve feet in breadth, or height, and in full bearing in every part. Here is a space of six hundred square feet, and, in case of a good crop, four peaches at least in every square foot, making, in the whole, 2,400 peaches, which would fill little short of ten or twelve bushels. This is to be seen any year at MONTREUIL in France. To be sure, these trees are tied to trelises, and have walls at their back; but, this climate requires neither; and, surely, fine trees and fine fruit and large crops may be had in a country where blights are almost unknown, and where the young fruit is never cut off by frosts, as it is in England and France. To preserve the young fruit in those countries, people are compelled to cover the trees by some means or other, in March and April. Here there needs no such thing When you see the blossom, you know that the fruit is to follow. By looking at the Plan of the Garden, PLATE I, you will see, that the Plats, No, 8 and 9, contain 30 trees and the two vine-trelises. The Plats are, you will remember, 70 feet long and 56 wide. Of course, putting 5 trees one way and 4 the other, each tree has a space of 14 feet, so that the branches may extend horizontally 7 feet from the trunk of the tree, before they meet. In these two Plats 14 feet wide is left clear for the grape vines. — These 30 Peach-trees, properly managed, would yield more fruit, even in bulk, than a large orchard in the common way; and ten times as much in point of value; the size as well as the flavour of the fruit are greatly improved by this mode of culture. — However, the sort is of very great consequence. It is curious enough, that people in general think little of the sort in the case of peaches, though they are so choice in the case of apples. A peach is a peach, it seems, though I know of no apples between which there is more difference than there is between different sorts of peaches, some of Munich melt in the mouth, while others are little better than a white turnip. — The sort is, then, a matter of the first importance; and, though the sorts are very numerous, the thirty trees that I would have should be as follows: 1 Violette Hative, 6 Early Montaubon, 1 Vanguard, 6 Royal George, 6 Grosse Mignonne, 4 Early Noblesse, 3 Gallande, 2 Bellgarde, 2 Late Noblesse. These are all to be had of Mr. PRINCE, of Flushing, in this island, and, as to his word, every body knows that it may be safely relied on. What is the trifling expense of 30 trees! And, when you once have them, you propagate from them for your life. Even for the feeding of hogs, a gallon of peaches of either of the above sorts is worth twenty gallons of the poor, pale, tasteless things that we see brought to market. — As to dried peaches, every body knows that they are managed as dried apples are; only that they must be gathered for this purpose before they be soft. 319. PEAR. — Pears are grafted on pear-stocks, on quince-stocks, or on those of the white-thorn. The last is best, because most durable, and, for dwarf trees, much the best, because they do not throw up wood so big and so lofty. For orchards, pear-stocks are best; but not from suckers on any account. They are sure to fill the orchard with suckers. — The pruning for your pear trees in the garden should be that of the peach. The pears will grow higher; but they may be made to spread at bottom, and that will keep them from towering too much. They should stand together, in one of the Plats, 10 or 11. — The sorts of pears are numerous; the six that I should choose are, the Vergalouse, the Winter Bergamot, the D'Auche, the Beurre, the Chaumontelle, the Winter Bonchretian. 320. PLUMS. — How is it that we see so few plums in America, when the markets are supplied with cart-loads in such a chilly, shady, and blighty country as England. A Green-gage Plum is very little inferior to the very finest peach; and I never tasted a better Green-gage than I have at New York. It must, therefore, be negligence. But Plums are prodigious bearers, too; and would be very good for hogs as well as peaches. — This tree is grafted upon plum-stocks, raised from stones by all means; for suckers send out a forest of suckers. — The pruning is precisely that of the peach. — The six trees that I would have in the garden should be 4 Greengages, 1 Orlean, 1 Blue Perdigron. 321. QUINCE. — Should grow in a moist place and in very rich ground. It is raised from cuttings, or layers, and these are treated like other cuttings and layers. Quinces are dried like apples. 322. RASPBERRY — 4 sort of woody herb, but produces fruit that vies, in point of crop as well as flavour, with that of the proudest tree. I have never seen them fine in America since I saw them covering hundreds of thousands of acres of ground in the Province of New Brunswick. They come there even in the interstices of the rocks, and, when the August sun has parched up the leaves, the landscape is red with the fruit. Where woods have been burnt down, the raspberry and the huckle-berry instantly spring up, divide the surface between them and furnish autumnal food for flocks of pigeons that darken the earth beneath their flight. Whence these plants come, and cover spots thirty or forty miles square, which have been covered with wood; for ages upon ages, I leave for philosophers to say contenting myself with relating how they come and how they are treated in gardens. — They are raised from suckers, though they may be raised from cuttings. The suckers of this year, are planted out in rows, six feet apart, and the plants two feet apart in the rows. This is done in the fall, or early ii the spring. At the time of planting they should be cut down to within a foot of the ground. They will bear a little, and they will send out several suckers which will bear the next year. — About four is enough to leave, and those of the strongest These should be cut off in the fall, or early in spring, to within four feet of the ground, and should be tied to a small stake. A straight branch of Locust is best, and then the stake lasts a life-time at least, let the life be as long as it may. The next year more suckers come up, which are treated in the same way. — Fifty clumps are enough, if well managed. — There are white and red, some like one best and some the other. To have them fine, you must dig in manure in the Autumn, and keep the ground clean during the Summer by hoeing. — I have tried to dry the fruit; but it lost its flavour. Raspberry-Jam is a deep-red sugar; and raspberry-wine is red brandy, rum, or whiskey; neither having the taste of the fruit. To eat cherries, preserved in spirits, is only an apology, and a very poor and mean one, for dram-drinking; a practice which every man ought to avoid, and the very thought of giving way to which ought to make the check of a woman redden with shame. 323. STRAWBERRY. — This plant is a native of the fields and woods here, as it is in Europe. There are many sorts, and all are improved by cultivation. The Scarlet, the Alpine, the Turkey, the Haut-bois, or high-stalked, and many others, some of which are white, and some of so deep a red as to approach towards a black. To say which sort is best is very difficult. A variety of sorts is best. — They are propagated from young plants that grow out of the old ones. In the summer the plant sends forth runners. Where these touch the ground, at a certain distance from the plant, come roots, and from these roots, a plant springs up. This plant is put out early in the fall. It takes root before winter; and the next year it will bear a little; and send out runners of its own. — To make a Strawberry-bed, plant three rows a foot apart, and at 8 inches apart in the rows. Keep the ground clean, and the new plants, coming from runners, will fill up the whole of the ground, and will extend the bed on the sides. — Cut off the runners at six inches distance from the sides, and then you have a bed three feet wide, covering all the ground; and this is the best way; for the fruit then lodges on the stems and leaves, and is not beaten into the dirt by heavy rains, which it is if the plants stand in clumps with clear ground between them. — If you have more beds than one, there should be a clear space of two feet wide between them, and this space should be well manured and deeply digged every fall, and kept clean by hoeing in the summer. If weeds come up in the beds, they should be carefully pulled out. — In November the leaves should be cut off with a scythe, or reap-hook, and there should be a little good mouldy manure scattered over them. — They will last in this way for many years. When they begin to fail, make new beds. Supposing you to have five or six beds, you may make one new one every year and thus keep your supply always ample. 324. VINE. — See Grape. 325. WALNUT. — The butter-nut, the black walnut, the hickory or white walnut, are all inhabitants of the American woods. The English and French Walnut, called here the Madeira Nut, is too sensible of the frost to thrive much in this climate. Two that I sent to Pennsylvania in 1800 are alive, and throw out shoots every year; but they have got to no size, their shoots being generally cut down in winter. — Walnuts are raised from seed. — To preserve this seed, which is also the fruit, you must treat it like that of the Filberd, which see. — It is possible, that the Madeira Nut grafted upon the black walnut, or upon either of the other two, might thrive in this climate. |