|

CHAPTER II

AT "THE THREE CROWNS "

Chagford, Devon

"DO

you want to catch the train half an hour before the time?" inquired the

facetious Invalid, as Polly and I started off in the morning to walk to

the station instead of waiting for the hotel 'bus.

"We are on our way to ask a few questions. That always takes time," we

answer with dignity.

Polly's

theory, built on bitter experience, is that the American manner of

asking questions is not invariably understood in England; therefore,

after several mishaps, she says she has invented a better system. It

consists of fixing her eyes on the face of her listener, asking what

she wants to know carefully and concisely, putting her question in the

ordinary manner, then backward, then from the middle word toward both

ends, watching with care for any faint gleam of intelligence she may

see displayed in the listener's eye. At Yeoford, where we are to leave

the train for Chagford (our next halting-place), we wish to be very

sure that a 'bus is ready and waiting to take us over the eleven miles

of road connecting the railway with the town. A harrowing experience I

endured one unfortunate evening, and which threatened to extend itself

into an entire night at that small station of Yeoford, has made us

doubly wary.

The

English railroads being run on the principle that time is made for

slaves, the booking agent we found closely imprisoned in his little

cell. In spite of our imperative rappings, he never lifts his little

window until nearly train-time. Then fifteen people are kept waiting to

buy their tickets, while the obliging man (who, by the way, cannot

answer until he consults the time-tables) pulls down his book, and,

after careful search, tells us most civilly that we can surely depend

on finding the Chagford coach waiting if we take the train now due

here. He hands us out four "single thirds" through to Chagford, and

then goes on calmly distributing tickets to the patient crowd that has

by this time increased to the number of twenty-five.

The train, of course, does not come in on time, nor does it hurry

itself to leave until ten minutes after time.

We

are serenely happy in the consciousness that, as this is the train the

coach is ordered to meet, the coach will wait for this particular

train, even if it is detained until midnight.

"So much for proper English law and order," says the Invalid.

The

judicious use of a little silver coin secures the privacy of a

third-class carriage quite to ourselves; we order two luncheon baskets

to be handed in at Salisbury, and then proceed to be comfortable in a

very civilized manner. The English luncheon basket is a consoler for

many things less delightful about their much abused railways. The

traveller orders lunch from the guard, the guard telegraphs ahead, and

at the station designated in comes a boy with a flat basket, for which

you give him three shillings and a couple of pennies as a tip. Inside

the basket is a bottle of wine, or cider, or beer, as the case may be,

half a cold chicken, some slices of ham, bread, butter, cheese, fresh

crisp lettuce, all daintily put together, with plates, a glass, and

Japanese napkins.

The

graceful spires of the Salisbury Cathedral point up into clear blue sky

as we fly across Salisbury plain, so long the dread of the early

travellers, who went by coach between Salisbury and Exeter by reason of

the interesting but somewhat interfering highwayman. Even a

highway-woman is said to have succumbed to the romantic temptation of

Salisbury plain, but she got hanged for her innocent fancy.

As

we approach Exeter, higher land begins to show itself on either side of

the line; and at St. David's, the second of the Exeter stations, comes

the cry "All out! Change for Yeoford!" and a sweet satisfied smile

breaks over my face.

"A

journey without change of carriage is no proper English journey,

especially on a through train," I tell my less experienced friends.

Yeoford

is but a short distance beyond Exeter, and after the first anxious

glance which discovers the 'bus ready waiting for us beside the

platform, we climb to the seat behind the driver, as the only

passengers, and settle ourselves comfortably for the eleven miles of

road before us.

When

at the top of the first high ground we look back, the gray mists of

Exmoor are far behind us. We know it is Exmoor because we trust the

driver implicitly for our geography, and it is he who points out to us

the land of Lorna Doone showing dimly on the horizon. Countless miles

of undulating meadow-land, flowing with honey and Devon cream at

sixpence a pot, spread between us and that region of romance.

The

ride to Chagford on the coach is not dashing; the horses have many

hills to pull up, and the driver's tender care, combined with the heavy

brake, prevents them from going down again too quickly. The setting sun

has prepared such a gorgeous spectacle in our honour that we should

have been satisfied that evening with even a slower pace. We came just

within sight of Kes Tor, the west directly facing us, when behind the

roundest hill in sight, the sun popped down looking like a huge orange

globe; then every sort of colour and shade of red, blue, green, and

purple, at once spread over the hills of the moorland in the

background, while the fertile valleys before us grew blue and misty as

we gazed down into them.

We

were almost at the end of the eleven miles, before the town showed

itself lying in a wide basin among the hills, a little bunch of white

houses, and a tall church tower giving back answering colours to the

brilliant sky. Our last hill was very steep, and, as we clattered down

into the narrow town street, we got a peep of the near-by furze-grown

moor, making a rough park for an old manor-house.

The

most fashionable hotel in Chagford is the Moor Park, but it had no room

for us, so we went on up the mounting street and over the market-place,

to "The Three Crowns," "a beautiful old mullioned perpendicular inn,"

so Charles Kingsley wrote of it.

Since

I had last been here, a new landlord and a good scrubbing, although

both somewhat modified the picturesque appearance of the interior, had

worked wonders for the greater comfort of guests. The musty smell of

centuries had fled before hot water and soap, new paper and fresh

furniture.

Our

party filled the entire house, as we did at "The Queen's Arms," though

the Invalid got a bedroom to herself quite large enough to hold us all

had we lacked other accommodation.

The

house was built by Sir John Whyddon, a worthy of the time of King Henry

VIII. It was his town mansion. He was a gentleman of enterprising

instincts; in fact, a self-made man. Born in Chagford, of a respectable

family, but one hitherto totally without fame, Sir John's youthful

ambitions took him to London, a most perilous journey when Henry VII.

was still king. Young Whyddon studied law, rose to be judge of the

king's Bench, became Sir John, and had the unspeakable honour of being

the first judge who rode to Westminster on a horse; previous to that

eventful occasion, mules had been considered quite good enough for

dignitaries of the law.

The Three Crowns, Chagford.

The

old house, with its iron-barred, deep-mullioned windows set in stone

frames, its thick walls, and stone floors, has sheltered in its young

days fine ladies and grim men-at-arms. On one of the stone benches

still within the entrance porch, there sank down, shot to death for his

loyalty to the Stuarts, Sir Sydney Godolphin, a gentle young

Cornishman, more poet than soldier.

The

thatched roof, green and brown with creeping moss, hangs thick above

the rough gray stones of the walls; while here and there about the

windows cling pink clusters of climbing roses. The Three Crowns has

been used as an inn for over a century. The old innkeeper who preceded

the present host, was noted far and near throughout Devon in his early

days for the excellence of his entertainment. Sorrow over the unhappy

marriage of a favourite son drove him and his excellent wife to habits

fatal to their business, and when that unfortunate party with which I

was detained at Yeoford came to The Three Crowns, the care of the

visitors was entirely in the hands of a little serving-maid, whose

endeavours to please were recorded in the guest-book. Her admirers

showed their honest appreciation by touching poems filled with such

substantial similes as:

"Lizzie's like a mutton chop,

Sometimes cold, and sometimes hot,"

or again:

"Good Lizzie had a little lamb, And so had we,

She served us well,

And so we were as happy as could be,"

a reflection, I fear, upon the lack of variety Lizzie's

larder displayed.

Pretty

Lizzie now has gone to delight London with her service, the poor old

hostess has died of excesses, and the old innkeeper, so many years host

of The Three Crowns, has been succeeded by the new young landlord,

whose bright little wife has tidied up the ancient inn. It now boasts a

bathroom, electric lights in the sitting-room, and owns neither stuffed

birds nor battered porcelain cups as decoration.

The

Matron remarked that the portrait of his Majesty, the king, we have in

our sitting-room "looks like a bird," but that observation, we

consider, is slangy and disrespectful.

Sir

John built his mansion near the church, facing the churchyard and

shaded by the tall elms which grow along the wall. The windows look

across the graveyard and a sunny valley to the low outlying hills of

Fingle Gorge. The great hall of the old mansion is now changed to a

schoolroom, where the little children of Chagford chant their lessons

in chorus, a system of education still fostered with care in

conservative England; we also hear them singing unaccompanied hymns

with that blissful disregard of time so common to their age. With these

efforts the attempt at their education appears to end.

That

Chagford is doing its best for the future of England and the colonies

is evident from the long lines of sturdy boys who lounge along the

churchyard wall, and the motherly little girls who care for large

families of babies under the shade of the tall trees.

Whatever

superstition moorland folk may have, and the writers tell us they revel

in the supernatural, the fear of ghosts certainly does not trouble this

village on the edge of Dartmoor. At night, after the children have

deserted the burial-place for their beds, the churchyard becomes the

trysting-place of lovers, and the lounging spot for the youth of the

village, who sit on the wall, and make night hideous with patriotic,

sentimental war-songs. The old men use it as a gathering-place, where

they gossip with their gaffers, and long after midnight footsteps of

solitary individuals can be heard strolling leisurely through a short

cut made between the lines of graves. "Early to bed and early to rise"

is a maxim which has evidently not yet reached Chagford.

The

town streets all radiate from the market-place. There is a quaint

octagonal building which the brave Chagford yeomanry use as an armory,

but where the market-cross was erected in earlier times. The low houses

are packed close upon the narrow streets, and, being built of stone

from the moors, are as solid as small fortresses. Their clay covering

is whitewashed, yellow-washed, or pink-washed, according to the fancy

of the owner, and there are moss-grown thatched roofs side by side with

those whose old tiles are coloured and tinted softly by the dampness.

That superlatively ugly structure, the modern brick villa, has crept

into the line, alas! and disfigures quaint Chagford as it does so many

of the old English towns.

Chagford

needs a Carnegie. Its public library has as custodian a youth who

divides his attention between the books and gardening, giving most of

his time to the latter more congenial occupation. He neither knows the

names of the books on the shelves, nor has he a catalogue to help the

reader. After we had paid a shilling to become reading-room members for

a week, he turned us loose among the scanty bookcases, and we made the

startling discovery that Phillpotts is without honour in the town he

has made famous in literature, and that even the prolific Baring Gould

is represented here but by one dilapidated old volume.

The

road past the library leads off through shady lanes to the hill whereon

Kes Tor sticks up like a monument, and it was to find this rocky beacon

that we took our first walk, armed with a road map, price one shilling.

The

road dips up and down, goes over narrow streams, past pretty hamlets,

and busy mills. The Tor smiled on us so invitingly from different

points of vantage that we tried various short cuts to reach it, with

appropriately disastrous results. The old rock instantly hid itself as

soon as we left the highroad, and never showed again until we came

meekly back, to be tempted and fooled another time. After many

failures, we were finally set right by a jolly, rosy, smiling, healthy

gamekeeper (minus teeth), who told us a way marked "private," which, in

our endeavour to be British and law-abiding, we had studiously avoided,

and which was not private at all, but, in fact, the only possible way

to reach our longed-for Tor.

"The way is but a bit beyond. Over the high moor."

So

we go a bit, and still several more bits, then suddenly we remember

that the English idea of "bits" is vague. When at last we came out on

the high moor the wind was so strong it nearly took us off our feet,

and the Tor was still very far away, according to American ideas of

remoteness. The bracken and the furze grew thick there about

prehistoric remains, lying scattered all around us.

A

long avenue of stones standing on end, like tombstones sunk deep into

the ground, led us straight to the ruins of funny little round huts,

roofless and demolished, yet sufficiently defined to show that they

once were dwellings for men. Into one of these we crept to rest and be

safe from the wind, and then discovered that in these apparently tiny

huts there is quite room enough for a reasonably sized family.

"As deceptive as a foundation," said the Matron, who once built a house.

The

view from these heights is superb. On all sides can be seen the low

swelling hills of the silent moor, one rising behind the other, as

though they went on in a never-ending perspective. At our feet lay the

houses and the church of Chagford, so clear and distinct and near that

we felt very much aggrieved at the long miles we had tramped. Beyond

the village the low hills stretched away, and away, and away, until

they lost themselves in the sky of the horizon.

The

hills on the moorland are all smooth and spherical. There are no trees

to break the line. Only here and there does a tor stick up from the

velvet surface like a stack of chimneys, and the carpet of soft green

colour is sometimes broken by the roads which look on the hillsides

like great crawling, yellow serpents. The whole landscape resembles a

sea whose huge waves have been arrested by magic just as they were

swelling to break. Somewhere in the distance are hidden those wild

valleys where range the "Hound of the Baskervilles," and Mr. Conan

Doyle's imagination, but nothing from our points of vantage suggested

savage wastes.

When

we left our hut for the shelter of the Tor to protect ourselves under

its shelf from the fierce wind, we found one of our choicest illusions

gone. The Tor, which looks so impressive from a distance, is but a

rocky excrescence on close examination.

The

heather was beginning to show its lovely pinkish-purple flowers on the

side of rough Scorhill, along which we strolled toward home through

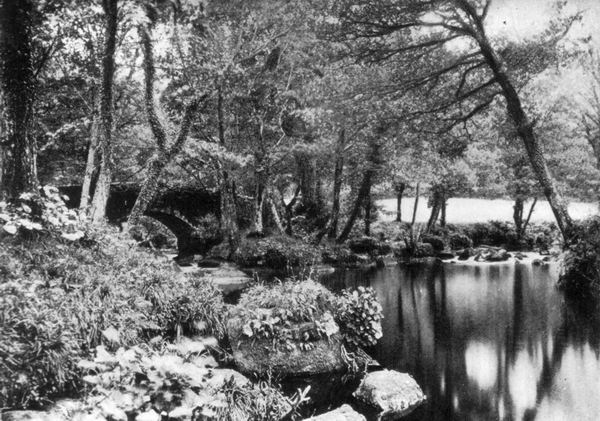

clover-fields until we reached the road. Leigh Bridge, so praised in

the guide-books, was on our path, and we stopped to lean over the rough

stone parapet and gaze at banks hung with purple rhododendrons, where

the North Teign leaps and pushes between mossy stones to join its

brother, the South Teign. The rivers there celebrate their reunion by

loud gurglings and bubblings and tumblings down a tiny waterfall. This

meeting-place is in the thick woodland full of flowering moss, pink and

white. The tall foxgloves carpet the ground, and by the roadside is a

hedge where wild roses and honeysuckle climb over the shining holly to

join the many wayside flowers, with the morning-glory vines running as

messengers between them all. There are not many choicer forest scenes

in the world than here at Leigh Bridge. Every tree is trimmed with ivy,

and every fallen log covered with flowering moss, and more wild flowers

than we ever saw together before.

Nearer

Chagford stands Holy Street Mill, greatly in favour with painters. It

is said no Academy Exhibition is ever without a copy of this bit of

woodscape. To nature's decoration on the banks of the quick-flowing

stream there is added a ruined mill and a delightful old Tudor

farmhouse embowered in roses, red, white, and yellow, built in a garden

as full of cultivated flowers as the near-by woodland is rich in wilder

blossoms.

Leigh Bridge, The Teign, Chagford

Chagford

has a street-cleaning department of one oldest inhabitant, who scrapes

the street vigorously all day and late into the night.

Chagford

has also an enterprising brass band which plays vigorously several

evenings each week, and Chagford has electric lights, and a fine

organist to play on its fine organ in its fine old Church of St.

Michael. The organ is comparatively new, and there is still a tradition

of the simpler days when the precentor marched up and down the aisle

whistling the hymn-tune for the congregation to follow with their

singing. The church is centuries old, and has curious carved bosses

along the vaulting of the ceiling, commemorating long-forgotten lords

of the manor. A huge iron key hangs near the monstrous lock on the

heavy ancient door: heraldic emblems, a little the worse for dust, are

still above the pews of the neighbouring gentry, and a quaint old

tombstone within the chancel marks the grave of Sir John Whyddon's

granddaughter. Her gentle charms and no less attractive virtues are set

forth in the following epitaph:

|

READER WOULDST KNOW

"Reader wouldst know who here is laid

Behold a Matron yet a Maid

A Modest looke A pious Heart

A Mary for the better Part

But drie thine eies Why wilt thou weepe

Such damsells doe not die but Sleepe"

|

The

Whyddon estate lies some five miles from Chagford, at Whyddon Park; and

in St. Michael's Church lie buried many descendants of the noted old

judge.

It

means a long drive to see the moor properly. All the low hills within

the boundaries of Chagford are outlying portions of Dartmoor, and on

one of these, Nattadown Common, amid the furze and the bracken, we

generally spent the evening, sitting at the base of an ancient cross

erected nobody knows when, watching a gorgeous sky display after

sundown.

It

is only a mighty pedestrian who can see the moors by tramping over

them. The most interesting part of this great romantic region does not

begin until the town has been left several miles behind. We accordingly

paid ten shillings, and in a comfortable wagonette, under the conduct

of our landlord, who has been a moor man1

some years, we started out one afternoon to see what we could of

Dartmoor between luncheon and dinner. A splendidly built road winds

about out along the sides of the billowy hills. The few poor acres of

farm-land scattered here and there around a lonely house beyond the

town were soon passed; then we passed into the great silent region.

Flocks of sheep cropping the sweet grass under the prickly furze, some

herds of bullocks below in the swampy hollows, the wild little

moor-ponies shaking their shaggy manes, and scampering off as we came

near, were all the signs of life we saw on the lonely green stretches.

"There is Grimspound," said our coachman.

Grimspound

is a prehistoric village. Our horse ready for a rest, we got out and

pulled ourselves up a rough path. It is quite worth the trouble.

At

least twenty-five of the queer little stone ruins are still traceable,

and one has been restored by antiquarians, the top covered over with

turf, the low entrance concealed by a semicircular wall, and restored

to what those learned in such matters think was the burrow of the human

animal. The village is surrounded by a rough stone wall, and the view

from the great height gave the savage man not only a chance to see

enemies miles away in that treeless country, but to keep watch over the

wanderings of his flocks. After Grimspound, the road twists itself

through a huge rabbit-warren, where millions of the little fellows

flash their tails in and out of their habitations. A desolate house

occupied by the warrener is here. In summer it is pleasant, but what

must the winter be! We were told that Eden Phillpotts, the writer, had

spent some months here. It may be that he was writing "The River" then.

There is one other habitation, some miles beyond the warren, an

exceedingly attractive house, closed and deserted.

"Too lonely for anybody but ghosts," ventured the Invalid.

"How do you suppose they ever got food here?" asked practical Polly.

"A

few trees grow," said the Matron, "why not potatoes?" which made the

driver smile. The trees in question were the scrubbiest of pines.

We

drove past the haunts of the ancient tin streamers, who made their

living on the moor when England was a young country by searching the

small rivers for metal. Here and there by the roadside we spied an

ancient cross put up by the monks centuries ago, to guide them from

parish to parish.

There

are still some mines open in deep glens. "Not very profitable," our

driver said. One, quite deserted, had the great wheel and ruined

windlass, like ghosts of the past, sticking out of the ground on a hill

all seamed and seared by the old workers. Near it still stands a

villainous-looking tavern not in very good repute. From the site of the

old mines we got a good view of the gloomy prison at Prince Town,

looming up against the sky on top of a hill miles away. Brilliant green

stretches of glittering bog-land lay below us, and our horse went down

a long, long hill with cautious steps, to stop at a pretty little inn

in a dale where there are actually full-grown trees. This is Post

Bridge, and dignified by the name of a village, although we see nothing

but the inn.

"The tea may not be good," said cautious Polly, "but it will be

refreshing after our long drive."

From

Post Bridge we returned home by new roads, but we had already seen the

chief characteristics of the moorland. Although different points of

view reveal different aspects, the scenery is all more or less the

same, and it is hard to imagine on this bright, smiling day that the

cruel blind mist, which so often leads travellers astray, can ever

settle down upon this open landscape, or that the blackness of night

can, as so often happens, envelop these green hills at noontime.

Dartmoor has moods, and, although the sadness of its face may be too

vividly described by the guide-book authors, the impression of its

lonely desolation is felt in the midst of bright sunshine.

The

moor-sheep and the rough cattle graze here on the hills, and sturdy

ponies range about at will, growing so wild that the poor little

fellows cry like children when they are first put into harness. In our

drive of several hours we saw only one man. He was a herder out looking

after the roaming cattle over which the duchy is supposed to have some

supervision. Each duchy tenant is allowed to keep on the moor as many

sheep and cattle as he can shelter in his own barns during the winter;

but human nature is weak, and not only does the rustic fail in honesty

occasionally, but a few of them have been known to go secretly out,

gather their neighbours' branded sheep, and drive them quietly with

their own to the nearest market, where they could sell them unnoticed,

although by such dishonesty they become but a few miserable shillings

richer.

Cranmere

Pool has the reputation of being the very wildest spot to be seen in

the whole extent of Dartmoor. The boldest members of our party longed

to get there. So far, we had seen nothing in our exploration which to

the transatlantic eye, accustomed to the scenery of our native land,

looked as wild as the descriptions we had read with awe. Our landlord

offered cheerfully to guide us to Cranmere, casually observing the

while, "The way is very tiresome, and there ain't nothin' to see but a

bog when you get there."

But

he does not know, as we do, that a bogey lives at Cranmere Pool, and a

very jolly bogey, too. In life he was the wicked Mayor of Okehampton,

and, having had the misfortune to die when such punishments were in

fashion, he was set about bailing out Cranmere Pool with a sieve.

Having been a very, very wicked person in life, he was up to a trick or

two after his death, so he searched about the moor until he found a

dead sheep, which he skinned, and with the hide he made his sieve

water-proof and well tightened. He then proceeded to flood Okehampton.

This game he found so entertaining that he refused his pardon, and has

continued ever since, when he is not busy sleeping, to repeat the joke.

As

Dartmoor covers one hundred thousand acres or more, we hardly had time

to explore the whole. We saw enough to be convinced that there was a

striking similarity about all the hills, all the bogs, and all the

lonely rabbit-warrens within its limits: The Hampshire uplands sink

into mole-hills before these great billowy heights, although, in

reality, the highest point of Dartmoor is not more than twelve hundred

odd feet above the sea-level.

Fingle Gorge

It

was the view of the heather just coming into bloom which started Polly

and me off on the walk to Fingle Bridge, one of the most romantic spots

about Chagford. The Matron and the Invalid went by carriage. They were

immensely pleased with the charming drive, but they lost the ramble

along the path beside the river and the intimacy we, who trudged,

gained with this most theatrical little gorge. Brilliant pink carpeted

hills on one side, fold into other hills opposite covered with green

young oak-trees; the tiny river dashes along in between, curving and

twisting all the way. No hill in the entire gorge would be hard to

climb, but the whole scenery is in such perfect proportion, river,

trees, rocks, and hills on so small a scale, that the tiny ravine has a

wild majesty not often found in nature. In places the heather-covered

slopes came so close to the water that we were forced to clamber over

the rough stones to find our path again; the trout shot in and out in

the clear babbling water, but no fishing with a bent pin is allowed

here. Fishing tickets must be got in Chagford. We lingered along the

grassy banks, fascinated by the bristling little stream, until we

reached the stepping-stones near the mill. Greatly to Polly's delight,

I lost courage half-way over, and was afraid to spring over the rushing

water until the continued quack of the mill ducks shamed me by their

very evident ridicule.

England

is no place for hurrying, and a sojourn in Chagford should be

lengthened to three weeks, to fully enjoy all the pleasure the woods

and the hills have here to offer. Although our plans allowed us but

little time for lingering, we stole another day for the sake of

visiting the Okehampton Saturday market-day.

A

market-day is the weekly dissipation, the one exhilarating spot in the

English farmer's summer life. The men come from far and near to

transact their business, to talk crops and live stock, the women to

gossip, and the dogs to exchange their opinions about driving sheep.

Okehampton not only has a fine market, but the town lies in the shadow

of a great Tor among the highest moorland hills. The ride thither on

the 'bus, all the sights of Okehampton, and our dinner at the best inn

cost but the sum of four shillings. Our economical treasurer therefore

permitted this unforeseen expense. The distance is eleven miles, and

along this road the view of the great plain of Devon, dotted with farms

and marked out by broad fields, is so expansive that it seems almost

boundless. The Invalid said she felt as if she were looking all over

the world.

The Stepping Stones

Along

this highway are scattered little villages with tiny, gaudy gardens

carefully protected by stone walls strong enough to hold back an army.

The proximity of the stone-strewn moor and the difficulties of hewing

the rock probably account for the huge stones used in building very low

fences and tiny cottages. The walls alone are thicker than the open

space in the houses. There is a copper mine being worked on this road

to Okehampton, but it looked neither rich nor prosperous to our eyes.

It may be both.

We

picked up market-goers at each hamlet and farm, and before we reached

Okehampton the coach-top was buzzing with the soft sound of a Devon

dialect almost incomprehensible to our American ears.

An

English market-place shows the nearest approach to bustling activity to

be found in the rural district. The pigs are scrubbed up, and the

cattle groomed down for the occasion. They arrive in droves, in

couples, or singly, at the eminently comfortable hour of ten in the

morning. "Pigs at eleven" means that the auction sales begin then. The

market auctioneer is a very important personage, often growing rich

from his business. He calls off the bids in shillings in a way that

drove poor Polly crazy. She always laboriously reduced them to pounds.

"Sixty? Seventy-five shillings? Eighty? Ninety-five shillings?" rolled

off with fluency, makes her wonder how much a fat porker knocked down

at ninety shillings is really worth. An extra fat sheep, or an

especially fine pig, is sometimes favoured with a ride behind its owner

in the dog-cart. These dog-carts roll in quickly from all sides, the

vehicles being built all on one and precisely the same pattern, and the

owner's rank or riches chiefly determined by the state of the carriage

paint and varnish. The horses are all such well-groomed, well cared for

beasts, that their condition gives small indication of their owner's

estate. The farmer himself scrubs up like his animals, puts on breeches

and gaiters, a cutaway coat, and, with his light waistcoat, white

stock, and carefully brushed hat, he makes an appearance which would be

no disgrace to a smart New York riding-school master. In this attire he

is thoroughly at home. He bestrides his horse, or drives his cart, and

even guides a wayward calf or a flock of fine sheep without any loss of

dignity, "but he does look like a bluff stage squire," said Polly.

The

shepherd's smock, so picturesque in olden times, has now given place to

an ugly linen coat. This garment seems to impel a shepherd to hold up

both arms and cry mildly: "Ho! Ho!" at intervals; the wearers of linen

coats allow themselves to indulge in no more forcible vehemence. The

calmness and the patience of the British country folk never shows

itself more agreeably than when they are driving live stock to market.

Some tiny pigs, who infinitely preferred the seclusion of a shop to the

market-pens, were pursued by men and boys without a sound. Gently they

waved handkerchiefs in the unruly little piglets' faces, as if "Pigs at

eleven" had never been the rule. A single farmer's boy in New England

can make more noise driving home two cows at night than we heard all

that day in Okehampton.

The

White Hart Inn has a fine big balcony over the front porch, and on this

we camped comfortably as in a private box to look down on the scene

beneath. The bullocks ran about, more or less alarmed by their unwonted

surroundings. Complaining calves were well protected by anxious

cow-mothers, who charged boldly at all possible enemies. Silly sheep

were kept out of the narrow doors by the watchful dogs, and the

grunting, fat, black swine ambled comfortably along.

It

is only after the serious business of the cattle auction is over that

the real excitement on the High Street begins. Then the farmers and the

squires gather in little groups, talking together, and emphasizing

every statement by striking against their leather gaiters with a

riding-crop, in good old theatrical manner. The farmers' wives go

shopping; John Ploughman lounges about, looking for employment, with

his cords tied by strings below the knees, and his loose red

handkerchief knotted about the neck. A few soldiers from the camp on

the moor add a bright touch, with their red coats, to the sober crowd;

the children run about everywhere quietly and happily, and the shepherd

dogs have grand romps with their kind, reserving contemptuous growls

for the town dogs.

Later

in the day, after the serious business of dinner is over, horses to be

sold arrive one at a time in the High Street, and show their paces. A

good-looking lot they are, from the little moor-pony who has only just

learned to obey a master to the great, lumbering farm-horse.

It

is a lengthy proceeding, this horse-selling in an English town; the

purchaser and all his friends look knowingly over every point of the

animal. He is made to go up and down the street again and again. The

small boy on his back rides him like a master; he shows off the horse's

gait, the tender condition of his mouth. The beast has been groomed

until he shines like satin, and his mane and tail are either carefully

waved, or tied up in fantastic style with straw. While this slow,

careful sale was going on, and there was no fear of meeting stray herds

of such wild animals as we had seen led meekly to market, we judged the

time safe to see the sights.

Okehampton

has a ruined castle hidden away in a park fit for the Sleeping Beauty.

Here rhododendrons, roses, and all the former cultivation of the great

garden have gone back again into wilderness, and have mingled with the

superb, great ivy-grown trees which shade the tumbled-down walls. Here

was a mighty castle. It clambered all over the hillside. A ghost still

haunts the spot. Lady Howard, once the supremely wicked mistress, in a

coach of bones, or bones herself, I have forgotten which, but anyway,

something very dreadful to see, travels each night from Tavistock to

pick a blade of grass; this task she must perform until all the grass

at Okehampton is plucked. What she did to deserve this fate, except to

be just wicked, no one in Okehampton seems to know, but she has been

very badly talked about for the last couple of centuries, and she

certainly has a hard task before her.

Under

Yes Tor, the most noted of Dartmoor's rocky piles, is a camp where all

the great artillery practice goes on. The noise of the big guns booms

over the entire moorland district, making certain parts of it rather

dangerous for excursionists, but there are warning notices in plenty.

The

ride home with a coach-load of soft-tongued Chagford folk was

delightful. They made great jokes with the driver about the sober coach

steeds, of whom he took the greatest care, never urging them at any

time, and putting them down the hills slowly with the aid of a heavy

brake. One lad on top jeered constantly at the slowest nag, named Dick,

until he was laughingly advised by the driver to "take Dick and ride he

home, for him's horses are no better than they," by which wise remark

it would appear that the personal pronoun on a Chagford tongue gets

hopelessly mixed. There are no confusing rules about the Devon English

grammar, nor, in fact, are there in our own New Hampshire, where I once

heard a farmer's boy roll off glibly "if I'd 'a' knowed that you'd 'a'

came, I wouldn't 'a' went."

It

was by way of Moreton Hampstead we decided to leave Chagford. It is

only five miles to the railway station by this road, and a coach makes

the connection many times each day. As compared with the drive either

to Yeoford or to Okehampton, the road is dull, although a Tor for sale

was pointed out to us. The way to Exeter by the railroad from Moreton

is delightful; the train runs around in and out among the cliffs on the

very edge of the South Devon sea. On this journey, while making one of

the usual changes at Newton Abbot, our most cherished object went

astray, namely, a straw creation, in the shape of a bag, baptized by

the Matron jumbo. Jumbo, like an omnibus, is never full. Jumbo opens a

capacious maw, and swallows all our trailers, from tooth-brushes to

unanswered love-letters. He smiles broadly on all the left-overs, after

the trunks have departed, and takes in every forgotten trifle. We all

had part and parcel in jumbo. He vanished on this trip.

We

had arrived in Exeter before his loss was discovered. The colour and

beauty of the green-topped red cliffs, the boats, the changing blue of

the sea, and the flat, paintable banks of the river Exe, had so

entirely absorbed our attention that no one noticed his loss. Jumbo was

the Matron's own private property and pet; when she discovered that he

had disappeared, she promptly fell upon me with reproaches, and the

assertion that it was to my care she had confided the precious charge

while she went looking for a porter.

I

had a certain indefinite sense of being guiltless, but I know myself to

be careless and forgetful. Then, too, I stand in such wholesome awe of

the Matron's wrath that I dared not contradict her statement. I fled to

that haven of all British travellers, The Lost Property Office.

"A

bag, a straw bag, left at Newton Abbot?" wrote down the chief clerk in

that most important institution; "it will be forwarded to you at

Bideford."

"But perhaps it's been stolen," hazarded the Matron, who had followed

me.

"Oh,

no, madam! It will be surely found," civilly concluded the official,

but we were not quite so confident in human honesty. With their present

surprising luggage system, the British railroads could not exist

without The Lost Property Office. Our train stood ready, and we ran in

answer to Polly's wild motions, jumped into a carriage we hoped was the

right one, trusting to Providence in the absence of proper indications.

With

a feeble toot-toot and many vigorous puffs of steam, we passed over the

bridge to St. David's, the square towers of Exeter Cathedral showing

among a crowd of houses on the hill behind us, and went on through the

high land till the railroad line dropped down slowly on to the low,

sedgy land meadows, where bright-tinted headlands stood up along

playful little inlet rivers running boldly into the land to make

believe they were the great sea itself.

Bideford

is built along one of these, named the Taw, and, when our train

stopped, we speedily transferred ourselves to the uppermost seat of a

high drag which was in readiness to take us to the New Inn at Clovelly.

_________________________

1 Meaning

one who looked after the Interest of the duchy in Dartmoor.

|