|

CHAPTER IV

CLERK'S HILL FARM

Evesham

"WE shall not lack variety on our

journey this morning," announced Polly, when she came back from the

ticket-office. "We change three times between Bideford and Evesham, and

unless we race after our luggage at each change, we shall surely share

the fate of a young English friend, who once confidentially told me she

never expected to see her trunk for three days after starting, if she

had changes to make on her journey. If her luggage appeared some time

during the week, she was satisfied. But we want ours to be in Evesham

when we step out there on the platform."

"But if the trunks are labelled they

will be all right," said the innocent Matron.

"And the Matron pretends she has

travelled!" sighed Polly, holding up her hands. Everything was labelled

and put in the van, excepting, always, wide-mouthed jumbo. The Invalid

even wanted him banished. She says she refuses to acquire the European

habit of stuffing the railroad carriage so full of personal belongings

that she cannot be comfortable herself.

The platform at Exeter is a scene of

wild confusion when we jump out to look after the luncheon-basket boy.

One or two of these youths are in eight, their arms laden down with

square baskets, none of which are evidently for us, as the boys pay not

the slightest heed to our calls, but proceed to unload their wares on

other wildly gesticulating passengers. Every woman, and several men,

who passed our carriage, asked us if this train went to such unknown

places that we became alarmed for our own safety. The only official in

sight was pursued by a bunch of clamouring travellers, and Polly

started to add one more to the throng, when we were partially convinced

we were in the right carriage by an old lady. She assured us that they

had asked seven porters and twenty-seven passengers if this train was

for Templecombe, and, as they all said "Yes," she thought we were safe

to remain where we were. She further added to our confidence by joining

us.

Polly then pursued a luncheon boy

through a forest of weeping farewells, and captured two baskets

intended for somebody else.

Considering the size of their country

and the exceeding cheapness of telegraphic communication, the English

are the most inconsolable of people when the cruel railway tears them

apart. Half the platform of every provincial station is given over to

groups of inhabitants who have come to speed a parting guest or

relative who probably needs help with her luggage, though the friends

usually come, not to help, but to weep. It is etiquette for the

departing traveller to hang out of the carriage door, embracing each

sorrowing friend at intervals, and then to wave a handkerchief as long

as the station remains in sight. After these exhausting efforts, she

usually sinks overcome on the cushions and falls to eating, no matter

what the hour be.

So we, too, fell on our luncheon,

because the Matron says that, "while eating delicious cold chicken, she

may dream of the baked beans of her native buffet car." Polly and I

joined forces at Templecombe in an exciting race for porters. We nearly

lost our lives by being run down by the platform baggage-trucks while

trying to wade in and out of a pack of hounds (most unwilling

travellers), who were being transported to some distant kennels along

our line.

"I thought you never would get back

alive," said the Invalid, who was hanging, in true English fashion,

half out of a carriage window she and the Matron had secured, for they

had watched our struggles with four small trunks and two big porters.

At last, after we had seen everything

shut up in the van, and determined how near that particular van was to

our carriage, we fell panting into the carriage, and the engine, with a

feeble toot, drew us away into a fair country of meadow-lands, and past

Bath the Famous, where the houses seem running down-hill to the Pump

Gardens like the belles and beaux of King George's time.

From Bath our way branched up north,

through Gloucester to Cheltenham, where again we changed. Luckily no

homesick canines were here in the way, and a comfortable old

grandfather of a porter quieted our nervous haste by telling us that

the train for Evesham would not be along for half an hour.

After leaving Cheltenham, we saw the

peaks of Great Malvern and the low, long ridges of the Cotswolds. Then

appeared pretty little stations among flower-beds, great stretches of

market-gardens, and soon we were in Evesham; so also was our luggage.

Our chosen stopping-place rather

disappointed us at first. The High Street, which leads from the

station, has evolved from a market-place and highway combined into a

town thoroughfare. It is broad, it is commonplace, and lined with the

conventional English brick houses, but the High Street luckily does not

go on for ever, and when it twists itself down to the river between

many ancient houses, and takes the new name of Bridge Street, the first

sad impression of this beginning of Evesham is dissipated. Our way to

the Crown Inn lies down this narrow way between the shops. Here we can

hardly get the Invalid along, so intent is she on staring at the queer

old lopsided Booth Hall, which occupies the centre of the open space at

the beginning of the contracted street, and an antiquated old

passageway that makes a splendid frame for the porch of All Saints'

Church.

"It is an old town, after all, isn't

it?" gracefully acknowledges the Invalid.

The courtyard of the Crown opens out of

the street just where the hill is steepest. It is an inn blessed with

possibilities which are completely lost, for want of a tidy mistress

and a wide-awake master. The Crown is old and it is well built, and

through the archway to the stable-yard we caught a fascinating glimpse

of the Bell Tower rising above old monastery meadows.

"I wonder if this place is inhabited,"

said Polly.

We wandered into the open inn door and

found our way to the coffee-room, where Polly jerked the bell violently

for several moments without any response. At last, in reply to an extra

violent long ring, a more or less untidy waiter appeared. She asked him

if there was no message for us in such sharp tones that he started off

on a trot, and soon brought back the anticipated note. Polly, upon

reading it, found that we could not get our lodgings until the morrow,

therefore should be obliged to put up at the inn. Off trotted the

waiter again, to return with a pleasant little woman, who took us up

the rickety stairs to palatial sleeping-rooms. My chamber proved to be

fully twenty-five feet square, with a style of furniture and

bed-hangings that made me expect to see the ghost of an

eighteenth-century belle before morning. The deep windows looked out on

a blooming garden and down a grassy sweep to the river. All the musty

smell of the old corridor and stairway was left where we found it; in

the great room sweet air blew in from the garden. We got a very decent

dinner after waiting for it, but then, waiting is good for the

appetite. The table-cloth was not exactly spotless, but every one in

the house proved so good-natured and careless that we had not the

courage to complain. Our stay was to be but one night.

The Evesham brass band was blowing forth

invitingly sweet strains in the Pleasure Gardens across the Avon,

tempting us to take a twilight stroll down the steep street to the

broad bridge at the foot. This bridge was built about fifty years ago

by Henry Workman, Esq., to replace a narrow but much more picturesque

structure. The same gentleman laid out the Pleasure Grounds, where the

band was playing. They form a charming promenade along the river bank,

and from the benches for loungers placed on the smooth lawns there is a

fine view of Evesham's crowning glory, the Bell Tower. The Avon flows

gently rippling past under the bridge, and is broader here than at any

other point near Evesham. Below the bridge the stream makes a sharp

bend about the old Abbey meadows, while above it the sedge grass grows

around an old mill, and little woody islands divide the water. On

either side of the stream the hills rise, narrowing the valley.

The people in the Pleasure Grounds were

still dancing on the turf to the music of the hand ar we turned

homeward to our Georgian beds. This furniture made Polly happy, even (l

she could not get her bell answered. She declares she loves everything

Georgian, even to the Georges themselves, and her extraordinary reason

is that, if George the Third had not been what she calls "An obstinate

fool! " (Polly is strong in her language), she would only have been

able to enjoy England from a colonial standpoint.

It was early next morning when we

started off toward our new lodgings on Clerk's Hill. Our landlady wrote

that she would be ready to receive us at any time after eight, so we

left the inn at half-past nine. It took fully half an hour to get our

bill paid. Every one at the Crown seemed so busy doing nothing. When

Polly, the treasurer, had disposed of this important business, she

indignantly informed us that the Crown was just as expensive as any

other country hotel in England where they "gave us service."

"Too bad such a delightful old place

isn't better managed," was the Invalid's farewell. We wandered about

looking at the sights in the town before crossing the river to the

country. Clerk's Hill is in the country.

"Let us first go through that passage in

the corner of the market-place behind the dissipated old Booth Hall,"

said the Matron.

"Dissipated?" said Polly. "The Booth

Hall is only rheumatic, and you would be rheumatic, too, if you had

been standing up for four hundred years."

The Matron took no notice whatever of

Polly's exception, but went on with her opinions.

"These solid ancient English buildings

all look to me," she said, "as though they had home-brewed beer for

breakfast, and fed on roast beef every day in the week. The houses, the

rustics, and the bulldogs of England look equally substantial and

jolly."

We dived through the archway and carne

out into the churchyard, where, among the grass-grown graves, rise two

graceful churches. Beyond, clear against the sky, stands the elegant

Bell Tower, the only remnant; of the former great abbey. Its perfect

proportions are made more graceful by lines of perpendicular

ornamentation. The churchyard is so quiet, au shaded by the tall trees

which grow about two houses of worship, that there could be no more

ideal resting-place for weary souls. The sunshine throws the shadow at

the Bell Tower across the graves, and the sweet bells hanging there

play quaint, old-fashioned tunes to mark the hours. Two

churches – one dedicated to St. Lawrence, the

other to All Saints – were built by the monks of the

old abbey; one was a chapel for pilgrims, the other for the use of the

town-folks. For many years after the suppression of the monasteries,

these churches stood bare, neglected, and left to decay, but they have

now been carefully restored to much of their ancient beauty. The main

aisles of the great abbey church, where the monks sang matins and kings

prayed, are now gardens for the townspeople of Evesham, enclosed in the

remnants of the church walls. Of the great tower, which rose into the

sky twice the height of the Bell Tower, nothing now remains, not even

foundations. The carved archway, which formerly led into the

chapter-house, is now an entrance to the town gardens. Evesham Abbey

was immensely rich and powerful, but every stick and stone was carried

off to build the houses, walls, and stables for miles around. The

suppressed abbey was let out as a quarry for many years after the

abbots were driven out of their possessions.

Not only did the abbots of Evesham own

the tongue of land which the bending Avon ,takes in its embrace, where

acres of the most fertile, abundant lands lie below the town, but all

over the county extensive farms, and the tithe-barns, which are still

standing in many places to tell the tale of enormous wealth. The

vanished abbey saw many stirring scenes. As a sanctuary for many

turbulent nobles, it was generously rewarded for the refuge it

afforded. It existed from before the Norman Conquest until Richard

Cromwell whispered in his master's willing ear that rich abbeys should

be suppressed for practical reasons.

Our way from the churchyard led us out

near the abbot's gate-house to the quaint little building, once the

almonry, where the monks distributed their alms to the poor. There are

many charming bits left within this tiny old structure, among others a

thirteenth-century fireplace, carved as monks could carve such things.

Boat Lane, down which we went on our way

to our new lodging between market-gardens and plum orchards, shows

traces of the old wall which the monks stretched across from the bend

of the river on one side to the turn on the other, and thus cutting off

a good-sized peninsula from the townfolk for their own use.

"What, ho! for the ferry!" sang the

Matron.

"This costs a ha'penny," finished Polly,

which is the fare over and back. A rope, worked by a very small boy,

pulls the flatboat across the river to the pretty ferry-house. Here we

went up the wooden steps to the shore, and then up a path through an

orchard, and through a rose-garden to our farmhouse lodging on the

steep hillside.

"Our luggage has come around by land, I

suppose," said the Matron, as if we meantime had been travelling over

the sea.

We voted for a week at Evesham. The

Matron desired to see great parks, the Invalid demanded visits to

ancient churches, Polly professed a weakness for quaint villages, and I

love the thrushes and the grassy lanes.

Then, too, clothes must be washed

sometimes, and these too rapid hotel laundry cleanings had left our

garments in sorry condition. It was the prospect of a week's stay which

had enticed us into lodgings where we could have peace and quiet, a

nice little maid to serve us, and give Polly a chance to do marketing,

a task she adores.

"I used to draw houses just like this on

my slate," declared the Matron, when she first saw the simple square

proportion of Clerk's Hill farmhouse, that would never tax the genius

of the artistic small boy. It was unostentatious. Its colour was light

yellow, but it had behind it the plumed elms of the green hillside, and

in front a sloping wilderness of roses, red, white, yellow, and pink.

Below the garden lay the grassy orchard, and still lower were the tall

trees, which line the bank of the glistening river over which we were

ferried. Floating up to our sitting-room windows came sounds of

merriment from the boating parties, from the small boys fishing along

the stream, and now and again the shrill whistle of the little toy

steamboat, The Lily, on which it is possible to go several miles to

Fladbury and return for the extravagant sum of sixpence. The passing of

The Lily, we found, threw the large family at the ferry-house into a

fever of excitement several times a day. The rope which guides the

ferry from shore to shore must be lowered, and The Lily leaves an oily

trail; both of these features excited the indignation of the numerous

small ferrymen and ferrywomen who work the boat.

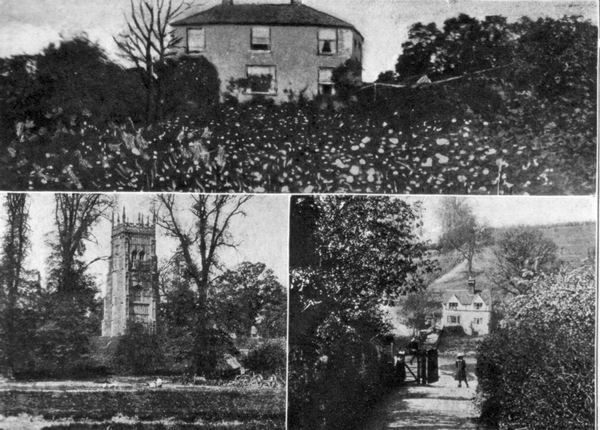

Clerk's Hill Farmhouse – The Bell Tower

– Boat Lane.

Our farmhouse could not have been less

than two centuries old, and it might have been even three. The charming

lattice windows at the back and sides, of the most approved Tudor

pattern, proved this fact. On the front, alas! they had been changed to

the ugly modern sort the French call "guillotine windows." The view

from our sitting-room and from my bedroom gave upon the broad plain to

the Cotswold Hill beyond; nearer, the red houses of the town gathered

about the Bell Tower, and the great clumps of feathery elms dotting the

meadows, the low, dark bunches of green we knew to be plum-trees, made

the landscape so ideally English that it was a constant delight. The

smell of the heavy-laden rose-bushes, the concerts we got early and

late the generous song-birds who lived in the orchard, would have been

quite enough to make a week in Evesham an enviable treat, without the

charm of the many delightful excursions possible in this district full

of interest to the lover of nature and the antiquarian. Evesham lies

within a network of good cycling roads, but Evesham also boasts a

motor-car, and one, too, which is the property of a young gentleman who

has made electricity his study. He knows every lovely view, every

ruined abbey, every old English church, every fine park and charming

old village within fifty miles, and he takes one to see them at a

charge of six cents a mile. This expense divided between the four or

five persons (a number the motor-car comfortably holds) was but a small

outlay for the pleasure we got with such an enthusiastic conductor.

There was no worrying about tired horses, no discussion as to the

number of miles we might go.

The walks about Evesham are over paths

leading among gardens and orchards, and these tramps gave us more

delight than either motor-car or bicycle.

"I don't see why I can't walk as far as

this at home," complained the Matron.

"Cooler air and better paths," decided

Polly, and the Matron meekly said no more.

To Cropthorne, the first village which

won our hearts, the walk was but a matter of three miles. We took the

morning for a stroll there, going nearly all the way through groves of

plum-trees laden with fragrant fruit or fields of the running dwarf

bean, showing gay scarlet or white blossoms. From the top of the ridge

behind the farmhouse, a hillside where in the old days the monks had

great vineyards, we went down the winding paths toward Breden Hill, a

member of the Cotswolds, which is cut off from the family, and

stretches verdant and shining before us on the left. The Cotswolds were

behind us over the hilltop, and Breden Hill looked like a great, lazy,

green animal with a nice, soft, round back as we walked toward it. The

high hills of Malvern, too, stood in the distance behind the woody

hollow where Cropthorne lies concealed. We turned on the road, leaving

Breden on the left, and suddenly came upon the beautiful little village

through a thick avenue of trees which led us to the Norman church, from

which we looked down Cropthorne's hilly street. Thatched cottages built

of white clay and black oak beams; low stone walls topped by hedges;

gabled porches; lattice windows open to sun and air, with stiff crimson

geraniums in pots on the ledges; plumy elm-trees and a glimpse down the

street far over a woody country, – that is Cropthorne

village. Inside its church are Norman pillars and arches, carved pews

of the thirteenth century, and two fine monuments erected in memory of

the Dineley family, who owned a manor-house not very distant. On the

first of these the good knight and his lady lie recumbent with folded

hands, while nineteen children, carved in high relief, kneel praying

around the pedestal. The grandchildren, of which there are also

several, are indicated by smaller figures carved above the heads of

their kneeling parents. On the second monument, dating from a

generation later, the knight and his lady kneel on a prie-dieu, and the

family about the base of the monument is somewhat less numerous. In all

of these carved effigies the costume of the period is most elaborately

reproduced. The marble is even painted, the better to represent the

dress, and the heraldic designs are coloured and profusely ornamented

with gold. The long inscription full of historical and mighty names

over the older tomb excited our curiosity, but it was so blurred that

we could only distinguish a few of the titles of the noble relatives.

The rich armour of the recumbent knight and the dress of his lady was

that of Queen Elizabeth's time; while the second gentleman and his wife

are clad in the sober garments of the Puritan regime. As we walked down

Cropthorne Street on our homeward way, among the lovely and picturesque

little cottages, we passed a line of easels, each with a painter behind

it, perched up on the side off the road. The old half-timber houses and

Breden Hill were being immortalized in a more or less artistic fashion.

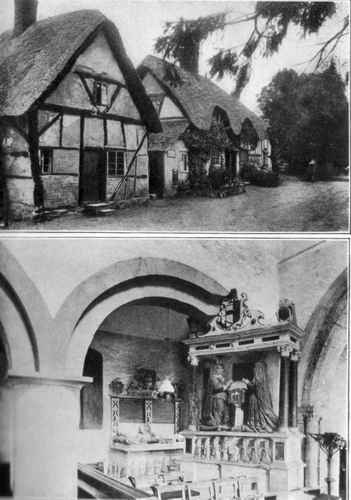

Cropthorne Cottages – Interior of Cropthorne Church

Another morning we paid our sixpence,

and puffed along the river in the little steamboat to Fladbury. The

Avon winds on its way there between shady banks, takes sudden twists

and turns past farm lands and old mills hidden among rushes. At

Fladbury Weir it stops. We then left the little boat and walked back to

Evesham by the road. Fladbury is quite a metropolis compared to

Cropthorne. We had lunch there at a little inn called the Anchor, where

an electric bulb hanging over the table called forth the information,

given with great pride by the tidy maid, that "Fladbury was far ahead

of Evesham in the way of lighting."

Fladbury is also on the railroad, which

is not always the case with most of the pretty villages hereabouts. It

is altogether a charming place with an individuality quite its own. A

short cut across the fields took us out on the road in front of the

estate of Fladbury's most distinguished neighbour, the Duc

d’Orléans. We stepped over a stile in front of the

half-French, half-English chateau he owns, just in time to interrupt

some village scandal, which we would have given worlds to have heard

through to the end. An old countryman in brown corduroy, leaning on his

spade, was solemnly saying to an audience of one groom on horseback and

a younger labourer:

"The old juke he come riding along the

road, with Madam Somebodyruther – " Just then we appeared.

The voice ceased, nor did it resume again until we were so far away

that we heard borne upon the breeze, "Madam Somebodyruther," which was

as near as we ever got to the rustic story concerning the French duke.

Wood Norton is the name of the famous

exile's place. The lodge gates are decorated with the monogram of the

royal Louis, – the entwined L of Fontainebleau and

Versailles. The little lodge-house is decorated with fleurs-de-lys cut

in the plaster. A fine royal crown is carved on the outside chimney,

while in strong contrast appear good solid English thatched cottages

clustering near the gate. The road back to Evesham, along which runs a

broad, comfortable foot-path, skirts Green Hill, where Simon de

Montfort fell in the decisive battle he waged against royal power in

1265, in the month of August, – the very month in

which we were walking past the battle-ground. The great earl had spent

the night at the abbey, having with him King Henry the Third, whom he

held as a hostage. Simon meant to fight Prince Edward after he had

joined the forces led by his son near Kenilworth, but the prince fell

upon the young Simon de Montfort, and, after routing him, marched

quickly to Evesham, forcing the earl, his father, into battle here on

Green Hill. Simon de Montfort fell fighting desperately for the

liberties of England.

In the manor-house grounds a column has

been erected in memory of this stirring event. The great earl's body

was cruelly mutilated by the royal followers, but the main fruits his

struggle, the desire of his soul, lives day in the British House of

Commons. Another day, across field and garden land, look the shortest

way to Elmley Castle, of a village nestling at the foot of Breden Hill.

It still preserves the same character it had when Queen Elizabeth made

the visit recorded by the wonderfully painted sign hanging in front of

the village inn. Upon this she is represented, in her broad hoop and

spreading farthingale, leading a procession of lords and ladies down

the village street. The village is probably a little cleaner to-day,

owing to more advanced theories, but the lords of Elmley Castle, who

have held the estate since the time of Henry the Seventh, have frowned

on the modern brick villa, and have kept this arcadian nest unspoiled

through all these centuries. The church is one of the most ancient in

the county, and the interior would be a delight to antiquarians,

without the fine alabaster effigies, which excite profound admiration.

In the churchyard is one of the most curious and quaintest of carved

sun-dials.

A great castle stood somewhere here on

the brow of the hill, but it was destroyed before the present mansion

came into existence in the reign of Henry the Seventh. The village

cottages were probably built about the same time, though some of them

may be older, and the village cross itself dates back so far that

nobody knows just when it was erected.

Two Academy pictures lately exhibited

have had Elmley Castle as a background. "The Wandering Musicians,"

which was exhibited in 1899, has the village cross, and another

picture, called "The Dead and the Living and a Life to Redeem," in

which the figures are moving about the old sun-dial, was hung in the

Academy this year. All around the base of Breden Hill are villages

which deserve a visit; quaint, simple old places, with ancient

churches, picturesque cottages, and a wealth of flowers. There is

Pershore, with its great Early English church and stone bridge; Wick

with its old-world houses; and Beckford with its wonderful box avenue.

The expedition to Elmley Castle ended

our long walks. We did the rest of our exploring in the motor-car.

Wickhampton, where Penelope Washington lies buried under a stone

bearing a coat of arms of the stars and stripes, is quite within

walking distance, but it is also an the way to Broadway. Turning aside

from the highway we stopped at a little church and manor-house where

had dwelt the young sin of George Washington. Her mother married in

second nuptials into the family, and she came to live in the

comfortable, homelike manor-house, which with its dove-cote and moat,

stands so near the dear little church where she sleeps her last sleep.

The house is half-timbered black and white, in the style so popular in

Queen Elizabeth's time. The great oak beams are warped here and there

by age, but it is withal so bright, so sunny, with its cheerful garden

and pleasant lawn, that you can only fancy happiness in such an abode.

Penelope Washington's grave in the

church is inside the chancel rail, and is placed at the foot of two

really splendid monuments erected to the memory of members of the

Sandys family. The fine effigies have escaped all mutilation, the gilt

paint on the canopies has defied the ravages of time, and the colours

of the heraldic shields are as fresh as when they were first put on.

The old church itself, with the narrow choir arch, the queer little

pulpit, and old pews, looks just as it did when gentle Penelope came

here with her mother to pray.

Broadway is five miles from Evesham,

built on the side of the Cotswolds, and has more of the dignity of a

very small town than the simple quality of a village. It is the resort

of artists, writers, and musicians. Abbey lived here for some time, and

the backgrounds of some of his illustrations were plainly taken from

sketches made in this village. Every one ought to trip around Broadway

in flowered brocade and quilted petticoats. The houses are all Tudor,

and there are but few gardens on the street. The Lygon Arms (the

Broadway inn) is a small mansion. Mine host, the picture of a rosy

country squire, showed us all over the charming old hostelry. Polly's

incredulity as to the age of the inn as an inn almost caused disaster,

and the Invalid's ire when Cromwell's bedroom was pointed out was a

close second.

Home of Penelope Washington – Last Resting-Place of

Penelope Washington.

"What was Cromwell doing here? He should

have been chasing kings," she broke out, though why Cromwell should not

have rested himself for pleasure in this very comfortable big chamber,

none of us except the Invalid knew, but she is intimate with historical

characters, and the rest of us are just a trifle ignorant, so we never

dispute her, for fear of being vanquished.

Mary Anderson lives in Broadway, and

owns a charming house at the top of the village street, while at the

other end, near the Green, lives Frank Millet. the painter.

"Broadway is beautiful, and Broadway is

stately, and Broadway is aristocratic, but I should prefer to paint

Elmley Castle, and I shall live in Cropthorne," said Polly. Broadway,

with an accent on the Broad, has other attraction beside the Tudor

houses, and, after we have had tea out of a broken-nosed teapot, which

the Invalid sneeringly calls "a Cromwell relic," bread, butter, and

jam, and paid a shilling and three pence each for the meal, we explored

the village a bit, and then started off where roads shaded by fine

trees led through undulating country to the beautifully kept park where

Lord Elcho's house, Stanway Hall, stands behind a superb gateway,

designed by Inigo Jones. Long avenues of trees and broad stretches of

turf and woody hillsides are at Stanway Hall, and a little beyond is

Toddington, once the estate of Lord Suddely, who proudly claimed

descent from that Tracy who distinguished himself by making away with

Thomas a Becket. One of the modern Lords of Suddely indulged in a fatal

taste for speculation, with the result that the great park is now in

the hands of a rich Newcastle collier.

Another pretty estate, Stanton, lies

nearer Broadway. Polly dwelt in the land of her favourite gentry. The

car ran past one estate after another, large and small parks and farm

lands, model villages, and the graceful arches which mark the ruins of

another vanished abbey, that of St. Mary Hailes. In this abbey, now

slowly falling, was preserved the bones of Henry of Almayn, a nephew of

King Henry the Third. He was slain in Italy by the sons of Simon de

Montfort in revenge for the part his father took against the earl.

According to the cheerful custom of the time, his heart was enshrined

in the tomb of Edward the Confessor, his flesh was buried in Rome, and

his bones at St. Mary Hailes, where the monks boasted of having the

real blood of Christ. If any town ever grew up about this abbey, it has

now completely disappeared. One solitary farmhouse remains near the

ivy-draped arches of the former cloister.

We saw evidences of the rule of the

abbots scattered all along our road in the huge tithe-barns or in

ruined chapels, which antedate the Norman period, and were evidently

established by the monks for the sake of the country people who lived

too far from the abbey to attend the churches there.

One week proved far too short, however,

permit even a glimpse at all the treasures of Evesham's neighbourhood;

the fates were against us. As every one knows, it sometimes rains in

England, and some of the rainiest days of our trip befell us in

Evesham. The skies began to let down torrents in the night, and, when

we came down to breakfast, there was a dreary drizzle falling on the

big bushes of La France roses in front of our window. It rained down on

the other roses as well, but somehow the gay pink bushes looked saddest

on the wet mornings. Polly we found standing in front of the small

grate looking as hopelessly disconsolate as the roses. A few sticks of

wood standing upright and one or two lonesome lumps of coal were trying

in vain to start into a glow.

"Why don't you send for the blower?"

said the Matron, her housekeeper's instinct at once alert.

"Why? why? Because a blower is an

unknown commodity in this house. The little maid has never heard of

one."

"Did you try sign language?" asked the

Invalid. "Perhaps blowers have perhaps other names here."

"Not only did I try sign language, but

the little maid looked at me with the rapture of a discoverer when I

held the newspaper up to cause a draught. She knows what blower means.

She says she has heard they had them down Birmingham way. The only help

she could give me was to lie prone on the floor and make a human

bellows of herself."

"It must be cheerful here on winter

mornings to get up and start life with that sort of a fire," the Matron

was beginning to say when our landlady came in with the coffee.

"English fires only ask to be let

alone," she said, finishing the Matron's remarks. "They will burn by

themselves without outside encouragement when they get ready."

This proved to be a fact. By the time we

had eaten breakfast, with cold shivers running down our backs, the fire

was beginning to show itself willing to warm us in a gentle English

fashion. A rainy day is famous for correspondence. Those who had no

letters to write did the family mending, and stared out the window

between stitches. The roses went on blooming and the birds kept on

singing, the far-away Cotswold changed colour every moment, going from

dark green to light yellow, from brilliant sea-green to dark blue. A

rainbow showed itself at intervals to deceive us, and the meadows and

plum orchards had moments of hopeful brightness, but the downpour kept

on In floods just the same.

Wet weather seldom troubles the English

pleasure-seeker, we observed, and on Our Rainy Day the little river

steamer went puffing along as usual. The ship's music (produced by the

lone effort of one cornet) sounded vigorously in the damp atmosphere,

and we even caught sight of an overgay passenger executing a jig quite

alone on the small deck.

The clouds broke late in the afternoon

to make way for a flaming sunset, and the new moon popped out of the

sky, a polished silver crescent. The red town roofs became even redder,

and a soft mist arose, marking the course of the Avon.

Polly and I got our feet into

"galoshes'' and started off to town. We found every shop closed, and we

were leaving on the morrow without half the photographs we needed! It

was Early Closing Day. Early Closing Day is the plague of the traveller

in England: You never know when you are coming upon it.

Each town has its own day in the week on

which it chooses to take an afternoon holiday. Promptly at two o'clock

every shopkeeper locks his door fast, and, from the chemist down to the

cobbler, the most vigorous knocking will not induce him to open an inch

for a customer. The shopkeeper and all his assistants then go off to

enjoy the afternoon, each in his favourite way.

We wandered down Bridge Street, properly

indignant, as becomes the American away from home, seeing the desired

photographs behind the glass of the windows to exasperate us, while we

shook the shop doors in vain.

"Why can't we console our sore hearts by

going to the theatre to-night?" I said.

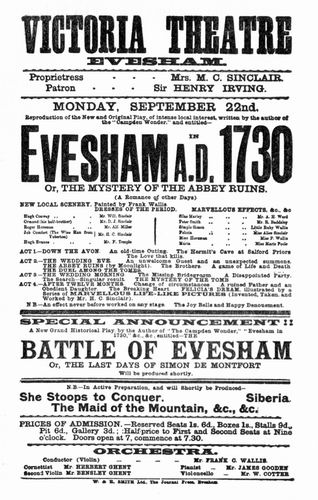

I had caught sight just then among the

pictures of a brilliant yellow playbill, on which stood in large

letters:

|

"EVESHAM THEATRE,

"MRS. SINCLAIR,

PROPRIETRESS,

"SIR HENRY IRVING,

PATRON."

|

followed by a most exciting list

of plays.

I had many a time looked with longing

eyes at the barn-like structure of combined corrugated iron and canvas,

which stood by a strong picket fence opposite the Pleasure Grounds.

This was the home of the drama in Evesham. We had no sooner revealed to

one another the innermost desire of our souls awakened by the brilliant

playbill than we started off in hot haste to secure tickets. Down we

went over the bridge, past the Pleasure Grounds, to where the "Victoria

Theatre" hung out a sign like an inn. But the high picket fence

protecting the playhouse had apparently no gate. Our anticipated

evening pleasure seemed slipping away from us.

"Perhaps the house is sold out and the

ticket-sellers have gone home," sighed Polly. No theatre is without its

hanger-on, who, if not the rose, would be near the rose, and a loiterer

without the sacred picket, seeing our longing looks, came to our aid.

"If you are looking for tickets," he

said, "here comes one of the young men. He will take you to Mrs.

Sinclair."

To Mrs. Sinclair! into the very presence

of the manager!

We approached timidly and were soon

following the youth through the yard of the Northwick Arms next door,

dodging behind sheds until we finally emerged in a broad field, where

were gathered a colony of travelling-vans. The young man led us to the

brightest and smartest of these little houses on wheels.

"Here's some ladies as wants good

tickets, Mrs. Sinclair," he called out. We had told him our business. A

smiling, pleasant woman appeared at the door and invited us to climb

the ladder-like doorstep into her home. We mounted with beating hearts.

All our desires were being fulfilled at once. We were going to see the

play, and, better still, the inside of one of those vans whose

possession we envied the commonest peddler.

Mrs. Sinclair lived in no gipsy fashion.

The outside of her van was as beautiful as a state carriage; the little

windows were adorned with boxes of trailing nasturtiums and curtained

with lace. Within, the cosy sitting-room had gas "laid on," an open

fireplace, a sofa and easy chairs, and goldfish swimming gaily around

in a big glass globe among the plants inside the window. I never took

much interest in goldfish before, but goldfish who lived in a

travelling-van became instantly different from those who only migrate

once in life from a bird-shop to a nursery window or dressmaker's

parlour.

The question of tickets was settled

speedily. We got the best places at eighteen pence each, and then were

invited to inspect Mrs. Sinclair's "little 'ome" and "h'airy bedroom"

next to the parlour. Clean and tidy it looked to us, although we were

begged to excuse the disorder because, the lady of the house said, she

had been "turnin' out," in other words, putting her belongings in

rights.

"The kitchen is in another van," she

told us; "we don't like to smell up our little 'ome."

Polly and I longed to be invited to

dinner, or even to tea, but time was flying; there were signs of

activity in the acting colony.

We saw figures going in and out of the

stage-door in the distant theatre, and Mrs. Sinclair told us that,

although half-past seven was the usual hour for beginning the play,

they sometimes opened earlier, if the crowd around the door was great

and vociferous. We had learned that the Victoria Theatre travels from

Evesham in the summer to Shakespeare's own town, Stratford upon Avon,

for the winter. The Victoria Theatre is a theatre rich in financial

advantages. The scenic artist is leader of the orchestra, painter and

musician. The dramatist most popular with the audience is a member of

the company, all royalties being thus directed into the home treasury.

The company of actors is largely a family affair. I fancy that costumes

and properties are also home-made.

Pasteboard is saved by the ingenious

method of writing the name of the patron of the expensive seats upon a

bit of paper, which is put in the box-office to be called for. Another

praiseworthy custom of the Evesham theatre is the selling of half-time

tickets. If you dine late, you come late and pay less; or, if you go to

the play and are not pleased, you can leave before the play ends, and

so save money.

"Would we could do the same thing in New

York," said Polly, whose economical soul is often tortured by the

inability to get her money back when she is too bored to sit through a

play.

Our friends hailed our plan with joy,

and, although we hurried through our dinners, the attendance before the

gates must have been numerous and noisy that night, for, when we

arrived, shortly after half-past seven, the play was in full blast and

the house crowded to repletion. There were no half-time tickets sold, I

am sure; the play was too stirring. The drama dealt with an occurrence

near Evesham some hundred years ago, and was called the "Camden Wonder."

A man named Harrison the agent of an

estate, was out collecting rents, when he was seized by ruffians,

hurried on board a ship, and finally sold as a slave. His servant, one

John Perry, none too strong in his wits, went clean daft under the

stress of fright and anxiety, and declared that he had murdered his

master with the help of his brother and of his mother, who were tenants

of the man Harrison. So plausible was the crazy man's confession that

not only he, but his mother and brother were hanged, in spite of their

frantic protestations of innocence. Long years after this tragic event,

the missing man returned, to the horror of all concerned. It was this

stirring local tragedy we went to see, and it had lost nothing in the

hands of the actor-dramatist. The scene-painter, too, had produced

marvels of nature on the canvas. The orchestra had a lugubrious motif

for the miserable, sad servant, which was played every time he dragged

his weary shape across the stage.

Each act had numerous scenes. A

sprightly London detective of the nineteenth-century type was

introduced, to the delight of the three-penny seats,

– called by courtesy the gallery. He was a little out of

place in the eighteenth century, but he fulfilled his mission and spoke

up boldly.

We missed the first view of Mr.

Harrison. When we were ushered into our cushioned bench, he had left

the scene in bitter anger because John Perry's mother could not pay her

rent, but also because in the delinquent tenant's cottage he found his

son making love to a girl "too poor to be his wife." Our sympathies

were thus at once enlisted against " old Harrison," as he was called

throughout the play. We did not see anybody when we came in but John

Perry, a dark-visaged individual who had neglected to comb his hair,

and who found great difficulty in moving his jaw when he spoke, greatly

to the disgust of the three-pennyites. He had a ball-and-chain walk,

and we were against him from the first, but he told us all the news.

A quick change of scene gave the London

detective a splendid entrance in disguise. He captured two highwaymen

just by way of showing what he could do, and put the thrip'nnies in

such a state of excitement that they had to be quelled by the ringing

of a huge dinner-bell.

There were no evening dresses or stupid

conventionalities at the Victoria Theatre. The air was thick with

smoke, and a sentiment of home-like liberty prevailed. An orchestra of

one piano, one cornetist, and two violins dispensed music appropriate

to the drama, and a brilliant drop-curtain, representing a scene in a

world of imagination, occupied with its mysteries the intervals between

the acts.

Local dramas are highly popular at the

Evesham theatre. We longed to stop over for "Evesham in 1730," to be

given the next night. We were assured by a speech made by one of the

leading characters before the curtain that this drama was resplendent

with great effects of costume, electric lights, and scenery.

A friend who had once been present at

another exciting play, "The Battle of Evesham," told us that the queen

in this drama, gorgeous in splendid robes, stepped out of the

fireplace, which served as well for a portal, and, holding up her

jewelled finger, said, "Hush!" while the equally magnificent king

sprang forward, surprised and delighted, shouting, "My Yelenor!"

We believe this to be calumny. We lost

many points, doubtless witty and brilliant, owing to a somewhat

immovable jaw with which several of the actors were afflicted, and a

lisp or two among the actresses interfered sadly with their coherency,

but the accomplished elocutionists of the company treated the dreadful

letter "h" with respect. It was weak at times, but we felt its presence

always. The morning after our theatre-party treat, we took our way

toward Derbyshire by way of Tewkesbury, the town of the great battle,

of the great abbey, and of the great novel by Miss Mulock, "John

Halifax, Gentleman." Bright and early we bade a sad farewell to our

comfortable lodgings, to the roses, to the thrushes, the trees, and the

river, and we promised our gentle hostess to come back to her some day.

The Invalid filled the air with lamentations and regrets for the sights

left unseen; the Matron sighed for more picnic teas by the river; Polly

rejoiced in the small amount we had drawn from the treasury.

Tewkesbury is only fourteen miles from

Evesham, and we wished we might have found it possible to go there by

the motor-car, but we could not arrange it to every one's satisfaction,

so we were forced to go by the Midland Railway. It is a pleasant

journey by rail, and pretty little stations lie all along the route. At

Ashchurch we had the choice of waiting an hour for the train on the

branch road to Tewkesbury, or of walking two miles. This was an easy

matter to decide on a day when the sun shines down clear and bright on

a broad, straight road, such as the stationmaster pointed out to us.

The foot-path worn along the side proved that we were not the only

impatient souls who objected to waiting at Ashchurch Junction.

"We are getting to walk almost like

English girls. We have gone two miles in less than an hour," said

Polly, as we saw the beginnings of Tewkesbury on either side of us.

It was not so much of a feat, for the

road is perfectly even and almost without a curve. We had arrived

before the train.

Tewkesbury streets, full of ancient

half-timbered houses, have forgotten all about time. They are still

dreaming of the Wars of the Roses and the rule of the abbots. As we

made our way up the Church Street to the abbey, the irregular,

overhanging gables, the projecting galleries of centuries past, filled

our souls with artistic delight. At the end of it, almost blocking the

way, stands the Bell Inn, a most perfect specimen of sixteenth-century

architecture. It was the house which Miss Mulock took as the home of

Abel Fletcher in her novel.

"We will eat our luncheon here, and talk

about John after we have seen Tewkesbury," decided the Matron.

The Abbey Church is just across the

street from the Bell Inn. The street takes a sharp turn by the side of

the inn, and we did not see the great church behind the trees of the

churchyard until we were quite in front of the Bell. It is almost a

cathedral, rough and bold, as are all Norman structures.

The exterior of Tewkesbury Abbey Church

is bold rather than beautiful. It is strong, solemn, symbolic of the

times when it was built. The interior is very impressive.

"The grandeur of this nave, its great,

simple columns, stirs my religious nature very deeply," declared the

Matron, and we all silently agreed with her.

There is nothing so genuine, so

imposing, as the pure Norman. Norman architecture is a frozen choral.

The tombs about the choir are of much more ornamental character. One of

them, which is built about a horrible effigy of a monk long dead, has

the richest workmanship. It is said the upper part was the model for

the canopy for the throne in the House of Parliament. We were told the

brave little prince, last of the House of Lancaster, who perished so

cruelly in the battle of Tewkesbury, was buried here in the abbey,

together with many of the nobles who were killed on that fatal day. The

Despencer, who made himself hated as a king's favourite in the time of

the first Edward, was laid under a magnificent tomb, but it was

entirely destroyed at the time of the dissolution. The Duke of

Somerset, beheaded in Tewkesbury market-place after the battle, the

Duke of Clarence, who chose to perish through Malmsey wine, Lord

Wenlock, and many of the Despencer family, lie here under fine tombs.

Among these ambitious, warlike dead is a tablet to the memory of Dinah

Maria Mulock, – Mrs. Craik, – who

wrote the immortal history of a gentleman, a book as fresh, as

delightful to the young generation as it was to their grandmothers, and

which will bring more pilgrims to Tewkesbury than all the great

fighters now lying at peace in the Abbey Church.

The Bell Inn, Tewkesbury.

Tewkesbury has changed but little since

Miss Mulock's time. The Bowling Green, where readers of the novel will

remember that John Halifax and Phineas Fletcher had one of their first

intimate talks, is behind the Bell Inn, and the entrance is still

through the kitchen and fruit garden, – "a large

square, chiefly grass, bounded by its broad gravel walk; and above

that, apparently shut in as with an impassable barrier from the outer

world, by a three-sided fence, the high wall, the yew hedge, and the

river," – so Miss Mulock described the place. The yew

hedge is immensely tall, and over it can be seen the square tower of

the Abbey Church. There are comfortable arbours, where tea is served

from the inn, and the hedge has been cut away on the river side, making

a lookout in this direction upon the narrow Avon. The mill, once

belonging to the abbots, which Miss Mulock makes the terrible scene of

poor Abel Fletcher's angry madness, is still standing. Beyond and far

away over the green we could see small white sails on the Severn, which

seem to skim along the meadows, that is the broad plain on which York

and Lancaster ended the War of the Roses in the one great decisive

battle of Tewkesbury. Peaceful grazing cattle and a few boys with long

fishing-rods are the only dots on this huge land where once men fought

so savagely, brother against brother.

"It is big enough to furnish a

battle-ground for four armies at the same time," said the Invalid.

None of us have had enough warlike

experience to disagree with her. We know that here poor, unhappy,

ambitious Queen Margaret made her last stand for her husband and son,

and that here the brave young Prince of Wales, crushed by the insulting

blow from Edward of York's gauntlet, fell and was stabbed to death; and

that the weak husband, Henry of Lancaster, paid the price of this fight

by death in the Tower. Along the riverbank near the mill an ancient

group of houses are still standing which we like to think were there on

the day of the great victory of the House of York.

The narrow lanes and crooked streets we

have read of in "John Halifax" still lead down to the banks of the

Avon. Inside the Bell the low, square rooms with high, plain oak

wainscoting, where we eat our lunch, the countless queer cupboards in

the corners, the dark, winding staircase and the uneven floors, all

speak of an age as great as the abbey ruins. Our association with the

house, however, concerns that more modern and very real personage, John

Halifax, Gentleman, and we enjoy our lunch much better for feeling sure

we are in that room where, "to Jack's great wrath, and my (Phineas)

great joy, John Halifax was bidden, and sat down to the same board as

his master."

We walked down the narrow, winding

street on our way back to the station, with enough time before us to

stop and admire the interesting old buildings which have been so well

preserved. Tewkesbury was in a fair way, some thirty or forty years

ago, to lose most of its architectural treasures through neglect and

carelessness. Fortunately, some art-loving citizens took the matter in

hand, many of the decaying buildings were restored, the modern ugly

plaster fronts were torn off of others, the fine ancient carved beams

and supports thus exposed to view, the old casements mended, and the

curious gables preserved. During the course of these restorations some

wonderful old bits of architecture were discovered, and now the visitor

to Tewkesbury town can gaze on work done in the fourteenth century, or

even earlier. House fronts are here which looked down on the armed men

of the king-making Duke of Warwick, and on the gay doings of

Elizabethan nobles.

"It is cruel to rush us away from this

delightful old place," said the Matron, with her nose deep in the

sixpenny "Hand-Book of Old Tewkesbury;" "there are enough delicious old

houses to keep me busy for a week."

"Then you must come back again," said

stern Polly, flourishing the through tickets she had bought at

Ashchurch. "Our luggage is labelled Rowsley, and probably on its

changing way to Derbyshire at this very moment."

"Tewkesbury is not entirely without

modern comforts," observed the Invalid. "There is the bill-board of the

opera house."

"And what a play!" exclaims the shocked

Matron. "Here, with large, respectable families of small children

tumbling out of every doorway, they present 'The Gay Grisette!'"

The Treasurer softly laughed at the

Matron's virtuous indignation, and then shooed us along like hens to

catch our train.

"I don't see why we did not walk all the

way to Ashchurch," was what we sang in chorus. The station seemed about

two miles from the centre of the town, and a long part of the walk was

through such ugly new streets that we were sorry to have discovered

them in delightful old Tewkesbury. But, before the train took us off,

the view from the station platform of the winding Severn River, and the

battle-plain with the high hills of Malvern, looking dawn at a blue

distance on the square tower of the Abbey Church rising among the

trees, shut out the remembrance of the shabby new villas.

"Good-bye, Tewkesbury!" sighs the

Matron. "We are off for an afternoon. on the exciting railway of Great

Britain, but, if we had known how enchanting you were, even our

Treasurer should not have hurried us away from you."

|