|

CHAPTER

VIII

THE PEACOCK AND ROYAL

Boston

"WE are actually on our way to Boston at

last," said the Matron. We had left nothing behind in Mansfield but a

few shillings, and we rode on slowly as far as Nottingham, where we

were obliged to change again. There were no lace curtains in the

station at Nottingham, much to our disappointment. There appeared,

however, two very fat rams dyed a deep red. Their war-paint had

evidently struck inward, for all the porters were engaged in trying to

conduct the belligerent animals from one van to another. When the

warlike beasts were not engaging one porter with their horns, they were

executing flank movements on the others with their hoofs. The battle

was so exciting that we quite forgot about our train until industrious

Polly seized a porter, luckily too small to resist her, loaded him down

with belongings, and, before he knew what was being done, had steered

him into more peaceful quarters – the Boston train.

The prize rams were still fighting for

liberty. Nottingham Castle disappeared through the smoke of the busy

town, and then we were off through the country, – a

billowy country with very little woodland. The train passes near

Belvoir Castle, built on a high ridge. It looked very like Windsor

through the haze of the afternoon. The Dukes of Rutland have been

living at Belvoir ever since they deserted Haddon Hall, or, rather,

they have been living there since the younger branch of the Manners

family succeeded to the title.

Not long

after passing Belvoir and Sleaford Station, we came into the Fen

Country. When the Puritans left Lincolnshire for America, this vast

region was a savage tract, desolate, uncultivated, full of bogs and

ague. The inhabitants were a rude people who barely managed to exist by

the crops they got off the small patches of land they reclaimed from

the water. Now all this is changed.

The Big Drain flows along beside the

track as wide as a canal, and is spanned by bridges more or less

picturesque, and at intervals smaller drains run from all sides to meet

it. The fields are fertile and the farms look prosperous.

The style of architecture so much

admired, and so continually copied by the early settlers in New

England, is the architecture of the Lincolnshire Fens. Square houses

with long, slanting roofs, a door in the middle, and one or two windows

on either side of it, can be seen here in brick, quite like the wooden

reproductions that predominate in the old towns about Boston, Mass.

Before the Fens were drained, the roofs of the cottages were made of

the reeds so plentiful in the district, and this must have added a

decidedly picturesque quality to the little dwellings now made ugly by

dull slate. "The reeds have disappeared with the reclaiming of the

land, and we were told that it was hard now to find a good thatcher in

this part of Lincolnshire.

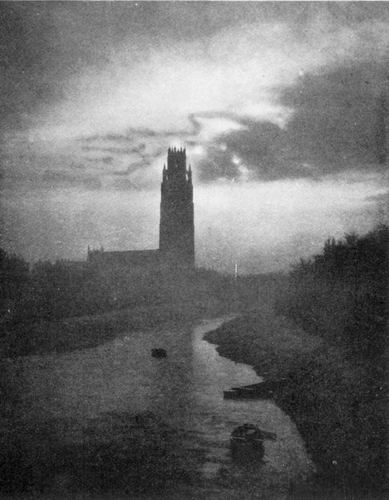

The dampness of the flat lands here is

responsible for the loveliest atmospheric effects. Over this otherwise

uninteresting plain there spreads at the sunset hour a most wonderful

colour. The air glows like gold, the drains glitter like molten metal,

and the wide fields and commonplace houses become glorified by the

light of the hour. It was through this golden mist that we first saw

the tall tower of St. Botolph's Church – the Boston

Stump, as it is called – looming gray before us. We

had reached Boston at last, after all our troubles!

Following the advice of a lady who

happened to be in the carriage with us, we gave our luggage to the 'bus

driver to take to the hotel, and walked there with our new-found

acquaintance by a short cut. Our guide was a Boston woman, and knew the

road, or we surely should have found ourselves as completely astray as

does the Western stranger in Boston, U. S. A.

On the street leading from the station,

down which we followed the Boston lady, the low brick houses were all

exactly alike, and out of them poured forth large families of dirty

children. After two minutes' walk through this uninviting beginning of

the town, the street suddenly stopped, and we stood above the parapet

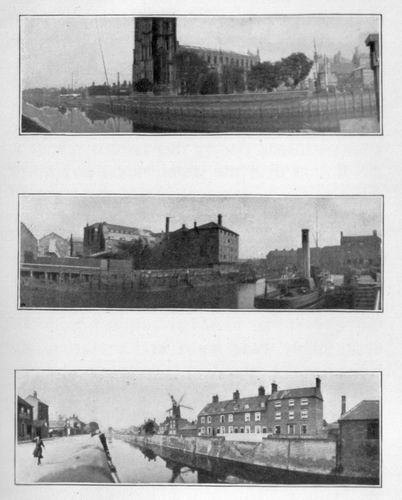

where the river ran swift beneath, and we looked across the water at

the great tower of St. Botolph's Church shooting up into the red sky.

This is the finest view in Boston, and,

as we saw it in sharp contrast to the dull commonplace street by which

we had come, our enthusiasm was correspondingly great. From this

spectacle we understood plainly why Boston is said, by the English, to

look like a Dutch town. Along the river gorgeously painted

fishing-boats were making their way out at high tide to The Wash.

Bridges spanned the river, and gardens grew along the side behind the

high walls required to curb the River Wytham's ardour. As a tidal

river, it has a way of climbing over barriers and even at intervals

invading the great church. Boston has no pleasant recollections of

these frolics. They have wrought horrible destruction, and once nearly

destroyed the whole town. From the river-bank we went to the bridge,

through a distracting maze of narrow lanes, before we reached our hotel

on the marketplace, as Polly observed, "quite Bostonese."

St. Botolph's Church, Boston.

The Peacock and Royal is a commercial

hotel of cheerful aspect. The front is decorated by bright flowers and

long trailing vines growing from the window-boxes on the balconies, and

above all is a most gorgeous sign of the most gorgeous of birds, from

which it takes its name. We ate our comfortable little dinner in the

coffee-room, our table placed in a "Dendy Sadler bow-window," behind

one of which the Matron has always pined to sit. It was nine o'clock

before we left the table. We were too tired to explore Boston's winding

ways, and, as it was too early for bed, I had this time secured a large

front room looking over the market-place, and my sleepy friends soon

found entertainment there.

The sound of a twanging banjo, which

came from beneath our window, gathered the few stragglers in the

market-place into a circle around the door of the Peacock. We could not

see the musician from our window, but he broke forth as soon as the

audience had gathered into the usual sentimental ballad dear to English

ears. Some boys, with dogs at their heels, formed the outside of the

meagre crowd, and then from a side street came belated mothers, pushing

their babies home in perambulators. Polly says that at no hour in the

twenty-four are English streets entirely free from perambulators, and,

late as it was, three of these useful carriages joined the circle, the

mothers, in true Boston fashion, being unable to resist music. The

audience grew larger and the circle wider; the songs were succeeded by

dialogues, and coppers rained plentifully into the collector's hand,

until a baby set up an opposition concert, and an enterprising dog was

encouraged by the noise to fight his four-legged neighbour. During the

rumpus which succeeded, the musicians vanished. The dog riot was

finally quelled, the babies trundled home, and the market-place in a

few minutes was absolutely deserted for the night.

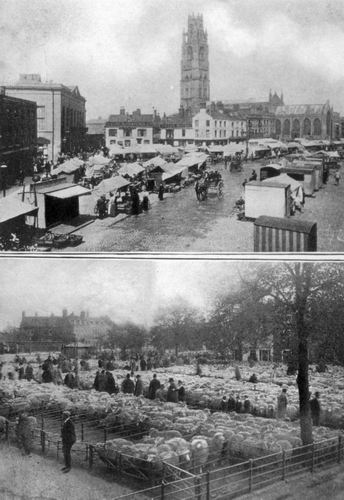

Next morning unwonted sounds of activity

got me out of bed at an early hour. Booths were being put up for a

market.

"We cannot seem to get away from

markets," the Matron said. "There is one in every town we visit. We

left the weekly market yesterday in Mansfield to find it to-day in

Boston."

Little houses on wheels are drawn

clattering over the stones, and take their places all in a row near the

inn. Then signs are hung out on each, announcing that within wonderful

seeds and infallible means of making the seeds grow are to be

purchased. The many canvas-roofed booths are soon taken in charge by

buxom market-women. They pile up fruit and vegetables which speak well

for the fertility of the Fen Country in each of these. We could hardly

wait to finish our breakfast, so interested did we become in what was

going on in the little outdoor shops. A descent into the market-place

revealed that they were not only occupied by market products, but

several were given up to the sale of the most wonderful and

tooth-destroying sweeties ever invented.

"No wonder there are not teeth enough to

go around in England!" exclaimed Polly, as she pointed in horror to a

perfect copy in extraordinary candy of the Royal Crown. Bright red

sugar on top, with deadly yellow confection below and silver stuck on

above ermine trimmings, it is as astonishing confectionery as can be

imagined. Piled high above the insignia of royalty were great cakes at

least fifteen inches around; a brilliant scarlet gelatine was smeared

on top and orange-hued candy appeared beneath. Pounds of a dark brown

brick-like sweet were piled up beside sugar sticks of surprising

manufacture that were at least two feet long and two inches thick.

"The motto goes all the way through the

stick," proudly announced the vender, as he broke up for our admiration

one of the great clubs, – pink on the edge, white in

the middle, with "Give me your heart" in black. These marvellous sweets

sold in packages of various weight from a penny upwards, and

disappeared more quickly than their outward appearance would warrant.

There were baskets so enticing in

another booth that the Matron and the Invalid walked all around town

laden down with wicker purchases. Onward we strolled through the

market-place, delighted with everything we saw, and Polly had hard work

to fix our wayward attention long enough to tell us that John Fox was

born in a house where now stands an inn called "The Rum Puncheon."

"What a jolly name for an inn," said the

Matron, who cares nothing for celebrities. The Invalid exclaimed "Fox's

Martyrs" at the same moment (that is all she knew about him, probably,

though she looked very wise.) The quaintest old building on the

marketplace stands next the Rum Puncheon, and is called "The Angel." We

forgot John Fox and all his writings at the next toy booth with its

penny wares. There were barrel-bodied horses, solemn-looking dogs, and

very woolly sheep, all of which the Matron wanted to take home with

her. The English children show the national love of animals by the toys

they choose.

Who has spent a day in old Boston and

not heard the town-crier? On this particular market-day that

functionary, in a somewhat shabby, sombre brown suit, brandishing a

huge, shiny bell, held the awestricken pink-cheeked market-women

entranced while he recited, in a stentorian voice, the dismal news: "A

ter-r-rible murder! Three victims dead! Murderer at large!" jingling

his bell so dismally that involuntarily we looked over our shoulders,

getting nearer to the loud-tongued bell, as though it could protect us.

The most enterprising member of the group hurried to the corner

news-stand, and came back with The Boston Post, wherein we read that

the murder had been committed fully twenty miles from the crier's bell,

so we might safely resume our explorations in the town without

colliding with the escaping wretch.

St. Botolph is at the farthest corner of

the market-place from the Peacock. We strolled there among the booths

and peered over the high wall, which protects the church from the

water, to find the rushing river of the night before was reduced by the

outgoing tide to the merest ditch. About St. Botolph's Church still

remained a close, with queer-looking, ancient structures with steep,

curious gables.

The church architecture is very foreign

in style, but modern English taste prevails in the restored interior.

The tower, piled up so high, lacks that finish on top, which only its

nickname, "The Stump," describes.

A very narrow lane between the old

houses, marked "Worm Gate," led away from the close. That the languages

are cultivated in this town was evident from a sign we saw there in a

tiny shop:

"L. KEPER, TAILOR D'HOMMES."

We left the Worm Gate on the broad road

along the Maud Foster Drain. Why Maud Foster nobody knows, but, as such

a person is known to have had business relations with the corporation

of Boston in 1568, it is supposed that the lady allowed the drain to be

cut through her property on condition that it should be called by her

name. It is as wide as a small river, has high walls on either side,

and the irregular red houses with the windmill twirling above them is

another touch of Holland. John Cotton and his friends did not take all

the east wind over the ocean with them when they left home. A good

portion of it we found blowing furiously along the Maud Foster Drain.

We turned from the drain to the Wide Bar Gate, a long open space of

pens, filled with red cattle and thousands of sheep for market. Above

the homesick bleating of the sheep arose the tones of "Rule Britannia,"

which were being flung into the teeth of the east wind by a choir of

small boys who had swarmed up on a monument made of cannon acquired in

some bygone Boston victory, and were bawling the tune to please the

shepherds. The Invalid soon began questioning a handsome farmer with

glowing cheeks, whose good looks were greatly enhanced by his

immaculate riding costume.

"This is the season for big sheep

markets," we heard him say, "and to-day there are a great many here,

but Boston once had a great market at which thirty-two thousand sheep

were sold."

The Invalid was duly impressed. She

tried other questions in her most fascinating manner, but ended by

joining us, with the remark: "Pity he knows nothing but sheep!"

Boston Market-Place – Sheep Market in the Wide Bar

Gate

The Red Lion Inn, which faces the Narrow

Bargate, has a more venerable exterior than the Peacock, but a

decidedly decayed interior. It owns to the age of four hundred years,

so no wonder that it is neither very clean nor very modern at the

present time. It was formerly the property of one of the Boston guilds,

and in the inn yard strolling players were wont to perform for the

delight of all Boston. At the other end of the market-place, past our

lodging at the Peacock, is the South End, a very familiar term to the

American Bostonian. The way there leads past Shod Friars Hall, an

antique, picturesque-appearing building. It seems almost cruel to be

forced to say it is but a restoration. Old Boston, which was founded by

hermits, was a famous place for friars. They were the revivalists of

olden times, and one family, the Tilneys, were so influenced that they

founded no fewer than three friaries in Boston, while a fourth, the

Carmelites, was endowed by a knight named De Orreby. For a small city,

Boston was in olden times unusually well provided with religion. Even

the celebrated guilds of Boston were semi-religious; nevertheless

Boston, of all English cities, showed early the strongest Puritan

spirit and the most decided sympathy with every action of the Reformed

Parliament in England.

On the way to South End there still

stand many old warehouses, and one of the largest, Mustard, Harrow

& Company, manufacture mushroom ketchup. Numerous houses of the

Georgian period, with broad gardens in front of them, proclaim this end

of the town – unlike its namesake in the U. S.

A. – a dwelling-place of the rich. Behind one fine

old mansion is the Grammar School, built in Tudor times. Boston,

England, is as proud of the scholars turned out by this famous school

as the Boston over the water ever has been of the glories of Harvard.

Once the home of those foreigners whose honesty gave the word

"sterling" to the English language, and a city so prosperous that, when

King John levied a tax on all merchants within the kingdom, Boston paid

the next largest sum to London, this city of the Fens has suffered from

the decay of its trade for several centuries. Its citizens and

corporation hope for great things in the future, with the completion of

a fine dock recently built and capable of receiving large ships.

There is almost no gentry living near

Boston, and no great estates in the neighbourhood. The Fen Country was

a desirable property with which the Crown dared reward the nobles in

the olden times. Now it is all so highly cultivated that there are no

covers for game. "No hunting, consequently no high society," said

Polly, regretfully.

The River Wytham and St. Botolph's Church – Old

Boston Warehouses – The Maud Foster Drain.

Old Boston town, which went to sleep

after the excitement furnished by the departure of their vicar, John

Cotton, and his followers, is now just beginning to wake up again.

There is still a very stern, solemn, Puritanical look about the dull

little Holland-like city, in spite of the numerous houses of

entertainment. Some of these rejoice in extraordinary names. There is

"The Axe and Cleaver," "The Loggerhead," "The Indian Queen," "The Ram,"

"The Whale," "The Unicorn," "The Red Cow," "The Blue Lion," and "The

Black Bull." They all furnish abundant liquid refreshment, with our

favourite "The Rum Puncheon," and the picturesque "Angel." Even the

streets have delicious names: "Paradise Lane," and "Pinfold Alley,"

"Liquor Pond Street" and "Silver Street," "The Worm Gate," "The Bar

Gam," Wide, and Narrow, and "Robin Hood's Walk." There is "Pump

Square," there is "Fish Loft Road," and in quaint "Spain Lane," in a

house since demolished, until she was fourteen years old, lived Jean

Ingelow, the writer. Boston is proud of its literary celebrities, and

has erected a statue to Herbert Ingram, the founder of the London

Illustrated News.

When we left Boston it was again the

late afternoon. The sky was flooded with brilliant orange, and light

clouds tinged with rose colour floated over the glowing surface. The

sails of the many windmills each showed colour or hue. They varied from

violet to bright orange. As we looked out of the window on one side of

the carriage the drains ran gold, while from the other side the colours

of the fields were doubly strong. Every leaf stood out, vivid and

distinct, on the fruit-trees, shaken and bent by the wind. The water of

the Big Drain ran dark, making the whiteness of the many ducks, which

were taking their evening swim, almost dazzling, and one dark gray

windmill on a high dike, with its sails pure white and a roof richly

red, looked like a painted toy. Not an inch of land in the Fen Country

is wasted. The well-tilled fields are divided by the drains or thick

thorn hedges; prosperous-looking haystacks are piled all over them,

promising good feed to the herds of cattle now eating the rich green

grass, and out of the rosy mist rises in the distance at intervals the

steeple of a village church, with a cluster of roofs about it. As soon

as we came upon an irregular gray stone farmhouse, with dormer windows

and picturesque thatched roof, we knew that we had left Lincolnshire

behind and were nearing Peterboro, where we changed for Norwich.

|