| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

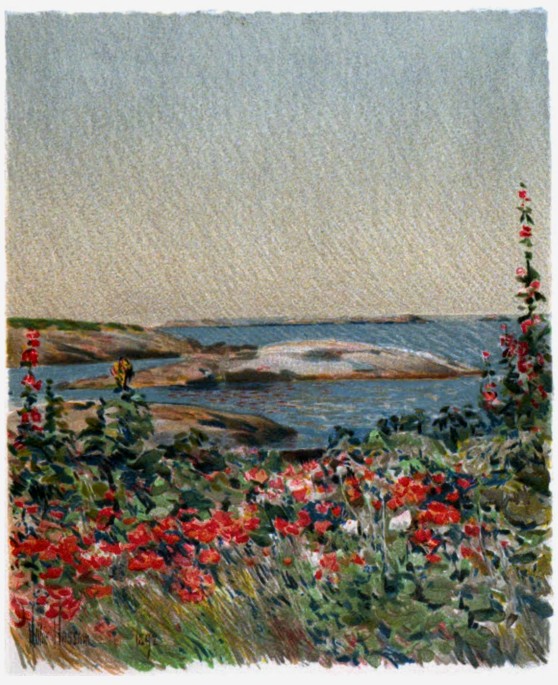

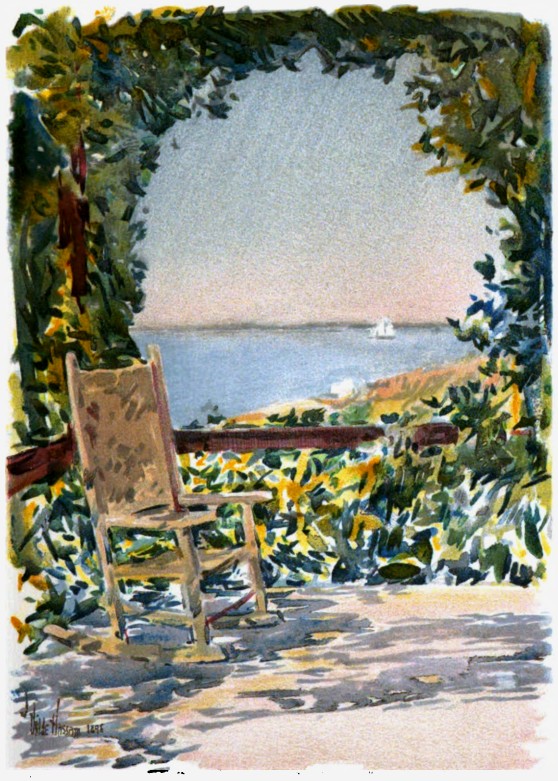

AN

ISLAND GARDEN

OF all the wonderful things in the wonderful universe of God, nothing seems to me more surprising than the planting of a seed in the blank earth and the result thereof. Take a Poppy seed, for instance: it lies in your palm, the merest atom of matter, hardly visible, a speck, a pin's point in bulk, but within it is imprisoned a spirit of beauty ineffable, which will break its bonds and emerge from the dark ground and blossom in a splendor so dazzling as to baffle all powers of description. The Genie in the Arabian tale is not half so astonishing. In this tiny casket lie folded roots, stalks, leaves, buds, flowers, seed-vessels, — surpassing color and beautiful form, all that goes to make up a plant which is as gigantic in proportion to the bounds that confine it as the Oak is to the acorn. You may watch this marvel from beginning to end in a few weeks' time, and if you realize how great a marvel it is, you can but be lost in "wonder, love, and praise." All seeds are most interesting, whether winged like the Dandelion and Thistle, to fly on every breeze afar; or barbed to catch in the wool of cattle or the garments of men, to be borne away and spread in all directions over the land; or feathered like the little polished silvery shuttlecocks of the Cornflower, to whirl in the wind abroad and settle presently, point downward, into the hospitable ground; or oared like the Maple, to row out upon the viewless tides of the air. But if I were to pause on the threshold of the year to consider the miracles of seeds alone, I should never, I fear, reach my garden plot at all! He who is born with a silver spoon in his mouth is generally considered a fortunate person, but his good fortune is small compared to that of the happy mortal who enters this world with a passion for flowers in his soul. I use the word advisedly, though it seems a weighty one for the subject, for I do not mean a light or shallow affection, or even an æsthetic admiration; no butterfly interest, but a real love which is worthy of the name, which is capable of the dignity of sacrifice, great enough to bear discomfort of body and disappointment of spirit, strong enough to fight a thousand enemies for the thing beloved, with power, with judgment, with endless patience, and to give with everything else a subtler stimulus which is more delicate and perhaps more necessary than all the rest. Often I hear people say, "How do you make your plants flourish like this?" as they admire the little flower patch I cultivate in summer, or the window gardens that bloom for me in the winter; "I can never make my plants blossom like this! What is your secret?" And I answer with one word, "Love." For that includes all, — the patience that endures continual trial, the constancy that makes perseverance possible, the power of foregoing ease of mind and body to minister to the necessities of the thing beloved, and the subtle bond of sympathy which is as important, if not more so, than all the rest. For though I cannot go so far as a witty friend of mine, who says that when he goes out to sit in the shade on his piazza, his Wistaria vine leans toward him and lays her head on his shoulder, I am fully and intensely aware that plants are conscious of love and respond to it as they do to nothing else. You may give them all they need of food and drink and make the conditions of their existence as favorable as possible, and they may grow and bloom, but there is a certain ineffable something that will be missing if you do not love them, a delicate glory too spiritual to be caught and put into words. The Norwegians have a pretty and significant word, "Opelske," which they use in speaking of the care of flowers. It means literally "loving up," or cherishing them into health and vigor. Like the musician, the painter, the poet, and the rest, the true lover of flowers is born, not made. And he is born to happiness in this vale of tears, to a certain amount of the purest joy that earth can give her children, joy that is tranquil, innocent, uplifting, unfailing. Given a little patch of ground, with time to take care of it, with tools to work it and seeds to plant in it, he has all he needs, and Nature with her dews and suns and showers and sweet airs gives him her aid. But he soon learns that it is not only liberty of which eternal vigilance is the price; the saying applies quite as truly to the culture of flowers, for the name of their enemies is legion, and they must be fought early and late, day and night, without cessation. The cutworm, the wire-worm, the pansy-worm, the thrip, the rose-beetle, the aphis, the mildew, and many more, but worst of all the loathsome slug, a slimy, shapeless creature that devours every fair and exquisite thing in the garden, — the flower lover must seek all these with unflagging energy, and if possible exterminate the whole. So only may he and his precious flowers purchase peace. Manifold are the means of destruction to be employed, for almost every pest requires a different poison. On a closet shelf which I keep especially for them are rows of tin pepperboxes, each containing a deadly powder, all carefully labeled. For the thrip that eats out the leaves of the Rosebush till they are nothing but fibrous skeletons of woody lace, there is hellebore, to be shaken on the under side of all the leaves, — mark you, the under side, and think of the difficulties involved in the process of so treating hundreds of leaves! For the blue or gray mildew and the orange mildew another box holds powdered sulphur, — this is more easily applied, shaken over the tops of the bushes, but all the leaves must be reached, none neglected at your peril! Still another box contains yellow snuff for the green aphis, but he is almost impossible to manage, — let once his legions get a foothold, good-by to any hope for you! Lime, salt, paris green, cayenne pepper, kerosene emulsion, whale-oil soap, the list of weapons is long indeed, with which one must fight the garden's foes! And it must be done with such judgment, persistence, patience, accuracy, and watchful care! It seems to me the worst of all the plagues is the slug, the snail without a shell. He is beyond description repulsive, a mass of sooty, shapeless slime, and he devours everything. He seems to thrive on all the poisons known; salt and lime are the only things that have power upon him, at least the only things I have been able to find so far. But salt and lime must be used very carefully, or they destroy the plant as effectually as the slug would do. Every night, while the season is yet young, and the precious growths just beginning to make their way upward, feeling their strength, I go at sunset and heap along the edge of the flower beds air-slaked lime, or round certain most valuable plants a ring of the same, — the slug cannot cross this while it is fresh, but should it be left a day or two it loses its strength, it has no more power to burn, and the enemy may slide over it unharmed, leaving his track of slime. On many a solemn midnight have I stolen from my bed to visit my cherished treasures by the pale glimpses of the moon, that I might be quite sure the protecting rings were still strong enough to save them, for the slug eats by night, he is invisible by day unless it rains or the sky be overcast. He hides under every damp board or in any nook of shade, because the sun is death to him. I use salt for his destruction in the same way as the lime, but it is so dangerous for the plants, I am always afraid of it. Neither of these things must be left about them when they are watered lest the lime or salt sink into the earth in such quantities as to injure the tender roots. I have little cages of fine wire netting which I adjust over some plants, carefully heaping the earth about them to leave no loophole through which the enemy may crawl, and round some of the beds, which are inclosed in strips of wood, boxed, to hold the earth in place, long shallow troughs of wood are nailed and filled with salt to keep off the pests. Nothing that human ingenuity can suggest do I leave untried to save my beloved flowers! Every evening at sunset I pile lime and salt about my pets, and every morning remove it before I sprinkle them at sunrise. The salt dissolves of itself in the humid sea air and in the dew, so around those for whose safety I am most solicitous I lay rings of pasteboard on which to heap it, to be certain of doing the plants no harm. Judge, reader, whether all this requires strength, patience, perseverance, hope! It is hard work beyond a. doubt, but I do not grudge it, for great is my reward. Before I knew what to do to save my garden from the slugs, I have stood at evening rejoicing over rows of fresh emerald leaves just springing in rich lines along the beds, and woke in the morning to find the whole space stripped of any sign of green, as blank as a board over which a carpenter's plane has passed. In the thickest of my fight with the slugs some one said to me, "Everything living has its enemy; the enemy of the slug is the toad. Why don't you import toads?" I snatched at the hope held out to me, and immediately wrote to a friend on the continent, "In the name of the Prophet, Toads!" At once a force of only too willing boys was set about the work of catching every toad within reach, and one day in June a boat brought a box to me from the far-off express office. A piece of wire netting was nailed across the top, and upon the earth with which it was half filled, reposing among some dry and dusty green leaves, sat three dry and dusty toads, wearily gazing at nothing. Is this all, I thought, only three! Hardly worth sending so far. Poor creatures, they looked so arid and wilted, I took up the hose and turned upon them a gentle shower of fresh cool water, flooding the box. I was not prepared for the result! The dry, baked earth heaved tumultuously; up came dusky heads and shoulders and bright eyes by the dozen. A sudden concert of liquid sweet notes was poured out on the air from the whole rejoicing company. It was really beautiful to hear that musical ripple of delight. I surveyed them with eager interest as they sat singing and blinking together. "You are not handsome," I said, as I took a hammer and wrenched off the wire cover that shut them in, "but you will be lovely in my sight if you will help me to destroy mine enemy;" and with that I turned the box on its side and out they skipped into a perfect paradise of food and shade. All summer I came upon them in different parts of the garden, waxing fatter and fatter till they were as round as apples. In the autumn baby toads no larger than my thumb nail were found hopping merrily over the whole island. There were sixty in that first importation; next summer I received ninety more. But alas small dogs discover them in the grass and delight to tear and worry them to death, and the rats prey upon them so that many perish in that way; yet I hope to keep enough to preserve my garden in spite of fate. In France the sale of toads for the protection of gardens is universal, and I find under the head of "A Garden Friend," in a current newspaper, the following item: "One is amused, in walking through the great Covent Garden Market, London, to find toads among the commodities offered for sale. In such favor do these familiar reptiles stand with English market gardeners that they readily command a shilling apiece. . . . The toad has indeed no superior as a destroyer of noxious insects, and as he possesses no bad habits and is entirely inoffensive himself, every owner of a garden should treat him with the utmost hospitality. It is quite worth the while not only to offer any simple inducements which suggest themselves for rendering the premises attractive to him, but should he show a tendency to wander away from them, to go so far as to exercise a gentle force in bringing him back to the regions where his services may be of the greatest utility."  From the Doorway One of the most universal pests is the cutworm, a fat, naked worm of varying lengths. I have seen them two inches and a half long and as large round as my little finger. This unpleasant creature lives in the ground about the roots of plants. I have known one to go through a whole row of Sweet Peas and cut them off smoothly above the roots just as a sickle would do; there lay the dead stalks in melancholy line. It makes no difference what the plant may be, they will level all without distinction. The only remedy for this plague is to scratch all about in the earth round the roots of the plants where their ravages begin, dig the worms out, and kill them. I have found sometimes whole nests of them with twenty young ones at once. Lime dug into the soil is recommended to destroy them, but there is no remedy so sure as seeking a personal interview and slaying them on the spot. They are not by any means always to be discovered, but the gardener must again exercise that endless patience upon which the success of the garden depends, and be never weary of seeking them till they are found. Another enemy to my flowers, and a truly formidable one, is my little friend the song-sparrow. Literally he gives the plot of ground no peace if I venture to put seeds into it. He obliges me to start almost all my seeds in boxes, to be transplanted into the beds when the plants are sufficiently tough to have lost their delicacy for his palate and are no longer adapted to his ideal of a salad. All the Sweet Peas, many hundreds of the delicate plants, are every one grown in this way. When they are a foot high with roots a foot long they are all transplanted separately. Even then the little robber attacks them, and, though he cannot uproot, he will "yank" and twist the stems till he has murdered them in the vain hope of pulling up the remnant of a pea which he judges to be somewhere beneath the surface. Then must sticks and supports be draped with yards of old fishing nets to protect the unfortunates, and over the Mignonette, and even the Poppy beds and others, I must lay a cover of closely woven wire to keep out the marauder. But I love him still, though sadly he torments me. I have adored his fresh music ever since I was a child, and I only laugh as he sits on the fence watching me with his bright black eyes; there is something quaintly comical and delightful about him, and he sings like a friendly angel. From him I can protect myself, but I cannot save my garden so easily from the hideous slug, for which I have no sentiment save only a fury of extermination. If possible, it is much the best way to begin in the autumn to work for the garden of the next spring, and the first necessity is the preparation of the soil. If the gardener is as fortunate as I am at the Isles of Shoals, there will be no trouble in doing this, for there the barn manure is heaped in certain waste places, out of the way, and left till every change of wind and weather, of temperature and climate, have so wrought upon it that it becomes a fine, odorless, velvet-brown earth, rich in all needful sustenance for almost all plants, — "well-rotted manure," the "Old Farmer's Almanac" calls it. But if there is no mine of wealth such as this from which to draw, there are many fertilizers, sold by all seed and plant merchants, which will answer the purpose very well: I have, however, never found anything to equal barn manure as food for flowers, and if not possible to obtain this in a state fit for immediate use, it is best to have several cart-loads taken from the barn in autumn and piled in a heap near the garden plot, there to remain all winter, till rains and snows and cold and heat, all the powers of the elements, have worked their will upon it, and rendered it fit for use in the coming spring. Many people make a compost heap, — it is an excellent thing to do, — piling turf and dead leaves and refuse together, and leaving it to slow decay till it becomes a fine, rich, mellow earth. In my case the barn manure has been more easily obtained, and so I have used it always and with complete success, but I have a compost heap also, to use for plants which do not like barn manure. As late as possible, before the ground freezes, I dig up the single Dahlia tubers (there are no double ones in my garden), and put them in boxes filled with clean, dry sand, to keep in a frost-free cellar till spring. I find Gladiolus bulbs, Tulips, Lilies, and so forth, will keep perfectly well in the ground through the winter at the Shoals. Over the Foxgloves, Iceland Poppies, Wallflowers, Mullein Pinks, Picotees, and other perennials, I scatter the fine barn manure lightly, over the Hollyhocks more heavily, and about the Rosebushes I heap it up high, quite two thirds of their whole height, — you cannot give them too much, only be careful that enough of their length, that is to say, one third of the highest sprays, are left out in, the air, that they may breathe. In the spring this manure must all be carefully dug into the ground round their roots. About Honeysuckles, Clematis, Grapevine, and so forth, I pile it plentifully, mixed with wood ashes, which is especially good for Grapevine and Rosebushes. But the white Lilies, and indeed Lilies generally, do not like to come in contact with the barn manure, so they are protected by leaves and boughs, and the earth near them enriched in the spring, carefully avoiding the contact which they dislike. When putting the garden in order in the autumn, all the dry Sweet Pea vines, and dead stalks of all kinds, which are pulled up to clear the ground, I heap for shelter over the perennials, being careful to lay small bayberry branches over first, so that I may in no way interfere with a free circulation of air about them. In open spaces where no perennials are growing I scatter the manure thickly, that the ground may be slowly and surely enriched all through the winter and be ready to furnish bountiful nourishment for every green growing thing through the summer. When the little plot is spaded in April, all this is dug in and mixed thoroughly with the soil. When the snow is still blowing against the window-pane in January and February, and the wild winds are howling without, what pleasure it is to plan for summer that is to be! Small shallow wooden boxes are ready, filled with mellow earth (of which I am always careful to lay in a supply before the ground freezes in the autumn), sifted and made damp; into it the precious seeds are dropped with a loving hand. The Pansy seeds lie like grains of gold on the dark soil. I think as I look at them of the splendors of imperial purples folded within them, of their gold and blue and bronze, of all the myriad combinations of superb color in their rich velvets. Each one of these small golden grains means such a wealth of beauty and delight! Then the thin flake-like brown seeds of the annual Stocks or Gillyflowers; one little square of paper holds the white Princess Alice variety, so many thick double spikes of fragrant snow lie hidden in each thin dry flake Another paper holds the pale rose-color, another the delicate lilacs, or deep purples, or shrimp pinks, or vivid crimsons, — all are dropped on the earth, lightly covered, gently pressed down; then sprinkled and set in a warm place, they are left to germinate. Next I come to the single Dahlia seeds, rough, dry, misshapen husks, that, being planted thus early, will blossom by the last of June, unfolding their large rich stars in great abundance till frost. They blossom in every variety of color except blue; all shades of red from faint rose to black maroon, and all are gold-centred. They are every shade of yellow from sulphur to flame, — king's flowers, I call them, stately and splendid. All these and many more are planted. For those that do not bear transplanting I prepare other quarters, half filling shallow boxes with sand, into which I set rows of egg-shells close together, each shell cut off at one end, with a hole for drainage at the bottom. These are filled with earth, and in them the seeds of the lovely yellow, white, and orange Iceland Poppies are sowed. By and by, when comes the happy time for setting them out in the garden beds, the shell can be broken away from the oval ball of earth that holds their roots without disturbing them, and they are transplanted almost without knowing it. It is curious how differently certain plants feel about this matter of transplanting. The more you move a Pansy about the better it seems to like it, and many annuals grow all the better for one transplanting; but to a Poppy it means death, unless it is done in some such careful way as I have described. The boxes of seeds are put in a warm, dark place, for they only require heat and moisture till they germinate. Then when the first precious green leaves begin to appear, what a pleasure it is to wait and tend on the young growths, which are moved carefully to some cool, sunny chamber window in a room where no fire is kept, for heat becomes the worst enemy at this stage, and they spindle and dwindle if not protected from it. When they are large enough, having attained to their second leaves, each must be put into a little pot or egg-shell by itself (all except the Poppies and their companions, already in egg-shells), so that by the time the weather is warm enough they will be ready to be set out, stout and strong, for early blooming. This pleasant business goes on during the winter in the picturesque old town of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, whither I repair in the autumn from the Isles of Shoals, remaining through the cold weather and returning to the islands on the first of April. My upper windows all winter are filled with young Wallflowers, Stocks, single Dahlias, Hollyhocks, Poppies, and many other garden plants, which are watched and tended with the most faithful care till the time comes for transporting them over the seas to Appledore. A small steam tug, the Pinafore, carries me and my household belongings over to the islands, and a pretty sight is the little vessel when she starts out from the old brown wharves and steams away down the beautiful Piscataqua River, with her hurricane deck awave with green leaves and flowers, for all the world like a May Day procession. My blossoming house plants go also, and there are Palms and Ferns and many other lovely things that make the small boat gay indeed. All the boxes of sprouted seedlings are carefully packed in wide square baskets to keep them steady, and the stout young plants hold up their strong stems and healthy green leaves, and take the wind and sun bravely as the vessel goes tossing over the salt waves out to sea. By the first of April it is time to plant Sweet Peas. From this time till the second week in May, when one may venture to transplant into the garden, the boxes containing the myriads of seedlings must be carefully watched and tended, put out of doors on piazza roofs and balcony through the days and taken in again at night, solicitously protected from too hot suns and too rough winds, too heavy rains or too low a temperature, — they require continual care. But it is joy to give them all they need, and pleasure indeed to watch their vigorous growth. Meanwhile there is much delightful work to be done in making the small garden plot ready. This little island garden of mine is so small that the amount of pure delight it gives in the course of a summer is something hardly to be credited. It lies along the edge of a piazza forty or fifty feet long, sloping to the south, not more than fifteen feet wide, sheltered from the north winds and open to the sun. The whole piazza is thickly draped with vines, Hops, Honeysuckles, blue and white Clematis, Cinnamon Vine, Mina Lobata, Wistaria, Nasturtiums, Morning-glories, Japanese Hops, Woodbine, and the beautiful and picturesque Wild Cucumber (Echinocystus Lobata), which in July nearly smothers everything else and clothes itself in a veil of filmy white flowers in loose clusters, fragrant, but never too sweet, always refreshing and exquisite. The vines make a grateful green shade, doubly delightful for that there are no trees on my island, and the shade is most welcome in the wide brilliancy of sea and sky.  A Shady Seat In the first week of April the ground is spaded for me; after that no hands touch it save my own throughout the whole season. Day after day it is so pleasant working in the bright cool spring air, for as yet the New England spring is alert and brisk in temperature and shows very little softening in its moods. But by the seventh day of the month, as I stand pruning the Rosebushes, there is a flutter of glad wings, and lo! the first house martins! Beautiful creatures, with their white breasts and steel-blue wings, wheeling, chattering, and scolding at me, for they think I stand too near their little brown house on the corner of the piazza eaves, and they let me know their opinion by coming as near as they dare and snapping their beaks at me with a low guttural sound of displeasure. But after a few days, when they have found they cannot scare me and that I do not interfere with them, they conclude that I am a harmless kind of creature and endure me with tranquillity. Straightway they take possession of their summer quarters and begin to build their cosy nest within. Oh, then the weeks of joyful work, the love-making, the cooing, chattering, calling, in tones of the purest delight and content, the tilting against the wind on burnished wings, the wheeling, fluttering, coquetting, and caressing, the while they bring feathers and straw and shreds and down for their nest-weaving, — all this goes on till after the eggs are laid, when they settle down into comparative quiet. Then often the father bird sits and meditates happily in the sun upon his tiny brown chimney-top, while the mother bird broods below. Or they go out and take a dip in the air together, or sit conversing in pretty cadences a little space, till mother bird must hie indoors to the eggs she dare not leave longer lest they grow chill. And this sweet little drama is repeated all about the island, on sunny roofs and corners and tall posts, wherever a bird house has been built for their convenience. All through April and May I watch them as I go to and fro about my business, while they attend to theirs; we do not interfere with each other; they have made up their minds to endure me, but I adore them! Flattered indeed am I if, while I am at work upon the flower beds below, father martin comes and sits close to me on the fence rail and chatters musically, unmindful of my quiet movements, quite fearless and at home. While I am busy with pleasant preparation and larger hope, I rejoice in the beauty of the pure white Snowdrops I found blossoming in their sunny corner when I arrived on the first of April, fragile winged things with their delicate sea-green markings and fresh, grass-like leaves. Ever since the first of March have they been blossoming, and the Crocus flowers begin, as if blown out of the earth, like long, lovely bubbles of gold and purple, or white, pure or streaked with lilac, to break, under the noon sun, into beautiful petals, showing the orange anthers like flame within. And the little Scilla Siberica hangs its enchanting bells out to the breeze, blue, oh, blue as the deep sea water at its bluest under cloudless skies. And later, yellow Daffodils and Jonquils, "Tulips dashed with fiery dew," the exquisite, mystic poet's Narcissus, and one crimson Peony, — my little garden has not room for more than one of these large plants, so early blossoming and at their end so soon. In the first week of May every year punctually arrive the barn swallows and the sandpipers at the Isles of Shoals. This seems a very commonplace statement of a very simple fact, but would it were possible to convey in words the sense of delight with which they are welcomed on this sea-surrounded rock! Some morning in the first of May I sit in the sunshine and soft air, transplanting my young Pansies and Gillyflowers into the garden beds, — father and mother martin on the fence watching me and talking to each other in a charming language, the import of which is clear enough, though my senses are not sufficiently delicate to comprehend the words. The song-sparrows pour out their simple, friendly lays from bush and wall and fence and gable peak all about me. Down in a hollow I hear the brimming note of the white-throated sparrow, — brimming is the only word that expresses it, — like "a beaker full of the warm South," — such joy, such overflowing measure of bliss There is a challenge from a robin, perhaps, or a bobolink sends down his "brook o' laughter through the air," or high and far a curlew calls; there is a gentle lapping of waves from the full tide, for the sea is only a stone's-throw from my garden fence. I hear the voices of the children prattling not far away; there are no other sounds. Suddenly from the shore comes a clear cry thrice repeated, "Sweet, sweet, sweet!" And I call to my neighbor, my brother, working also in his garden plot, "The sandpiper! Do you hear him?" and the glad news goes from mouth to mouth, "The sandpiper has come!" Oh, the lovely note again and again repeated, "Sweet, sweet, sweet!" echoing softly in the stillness of the tide-brimmed coves, where the quiet water seems to hush itself to listen. Never so tender a cry is uttered by any bird I know; it is the most exquisitely beautiful, caressing tone, heard in the dewy silence of morning and evening. He has many and varied notes and calls, some colloquial, some business-like, some meditative, and his cry of fear breaks my heart to hear when any evil threatens his beloved nest; but this tender call, "Sweet, sweet," is the most enchanting sound, happy with a fullness of joy that never fails to bring a thrill to the heart that listens. It is like the voice of Love itself. Then out of the high heaven above, at once one hears the happy chorus of the barn swallows; they come rejoicing, their swift wings cleave the blue, they fill the air with woven melody of grace and music. Till late August they remain. Like the martins', their note is pure joy; there is no coloring of sadness in any sound they make. The sandpiper's note is pensive with all its sweetness; there is a quality of thoughtfulness, as it were, in the voice of the song-sparrow; the robin has many sad cadences; in the fairy bugling of the oriole there is a triumphant richness, but not such pure delight; the blackbird's call is keen and sweet, but not so glad; and the bobolink, when he shakes those brilliant jewels of sound from his bright throat, is always the prince of jokers, full of fun, but not so happy as comical. The swallows' twittering seems an expression of unalloyed rapture, — I should select it from the songs of all the birds I know as the voice of unshadowed gladness. |