| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| IV GHOST STORY OF THE FLUTE'S TOMB 1 LONG

ago, at a small and out-of-the-way village called Kumedamura, about

eight miles

to the south-east of Sakai city, in Idsumo Province, there was made a

tomb, the

Fuezuka or Flute's Tomb, and to this day many people go thither to

offer up

prayer and to worship, bringing with them flowers and incense-sticks,

which are

deposited as offerings to the spirit of the man who was buried there.

All the

year round people flock to it. There is no season at which they pray

more

particularly than at another. The

Fuezuka tomb is situated on a large pond called Kumeda, some five miles

in

circumference, and all the places around this pond are known as of

Kumeda Pond,

from which the village of Kumeda took its name. Whose

tomb can it be that attracts such sympathy The tomb itself is a simple

stone

pillar, with nothing artistic to recommend it. Neither is the

surrounding

scenery interesting; it is flat and ugly until the mountains of Kiushu

are

reached. I must tell, as well as I can, the story of whose tomb it is. Between

seventy and eighty years ago there lived near the pond in the village

of

Kumedamura a blind amma2 called Yoichi. Yoichi was extremely

popular

in the neighbourhood, being very honest and kind, besides being quite a

professor in the art of massage — a treatment necessary to almost every

Japanese. It would be difficult indeed to find a village that had not

its amma.

Yoichi

was blind, and, like all men of his calling, carried an iron wand or

stick,

also a flute or 'fuezuka' — the stick to feel his way about with, and

the flute

to let people know he was ready for employment. So good an amma was

Yoichi, he

was nearly always employed, and, consequently, fairly well off, having

a little

house of his own and one servant, who cooked his food. A

little way from Yoichi's house was a small teahouse, placed upon the

banks of

the pond. One evening (April 5; cherry-blossom season), just at dusk,

Yoichi

was on his way home, having been at work all day. His road led him by

the pond.

There he heard a girl crying piteously. He stopped and listened for a

few

moments, and gathered from what he heard that the girl was about to

drown

herself. Just as she entered the lake Yoichi caught her by the dress

and

dragged her out. 'Who

are you, and why in such trouble as to wish to die?' he asked. 'I am Asayo, the teahouse girl,' she answered. 'You know me quite well. You must know, also, that it is not possible for me to support myself out of the small pittance which is paid by my master. I have eaten nothing for two days now, and am tired of my life.'

'Come,

come!' said the blind man. 'Dry your tears. I will take you to my

house, and do

what I can to help you. You are only twenty-five years of age, and I am

told

still a fair-looking girl. Perhaps you will marry! In any case, I will

take

care of you, and you must not think of killing yourself. Come with me

now; and

I will see that you are well fed, and that dry clothes are given you.' So

Yoichi led Asayo to his home. A few

months found them wedded to each other. Were they happy? Well, they

should have

been, for Yoichi treated his wife with the greatest kindness; but she

was

unlike her husband. She was selfish, bad-tempered, and unfaithful. In

the eyes

of Japanese infidelity is the worst of sins. How much more, then, is it

against

the country's spirit when advantage is taken of a husband who is blind?

Some three

months after they had been married, and in the heat of August, there

came to

the village a company of actors. Among them was Sawamura Tamataro, of

some

repute in Asakusa. Asayo,

who was very fond of a play, spent much of her time and her husband's

money in

going to the theatre. In less than two days she had fallen violently in

love

with Tamataro. She sent him money, hardly earned by her blind husband.

She

wrote to him love-letters, begged him to allow her to come and visit

him, and

generally disgraced her sex. Things

went from bad to worse. The secret meetings of Asayo and the actor

scandalised

the neighbourhood. As in most such cases, the husband knew nothing

about them.

Frequently, when he went home, the actor was in his house, but kept

quiet, and Asayo

let him out secretly, even going with him sometimes. Every

one felt sorry for Yoichi; but none liked to tell him of his wife's

infidelity.

One

day Yoichi went to shampoo a customer, who told him of Asayo's conduct.

Yoichi

was incredulous. 'But

yes: it is true,' said the son of his customer. 'Even now the actor

Tamataro is

with your wife. So soon as you left your house he slipped in. This he

does

every day, and many of us see it. We all feel sorry for you in your

blindness,

and should be glad to help you to punish her.' Yoichi

was deeply grieved, for he knew that his friends were in earnest; but,

though

blind, he would accept no assistance to convict his wife. He trudged

home as

fast as his blindness would permit, making as little noise as possible

with his

staff. On

reaching home Yoichi found the front door fastened from the inside. He

went to

the back, and found the same thing there. There was no way of getting

in

without breaking a door and making a noise. Yoichi was much excited

now; for he

knew that his guilty wife and her lover were inside, and he would have

liked to

kill them both. Great strength came to him, and he raised himself bit

by hit

until he reached the top of the roof. He intended to enter the house by

letting

himself down through the 'tem-mado.'3 Unfortunately, the

straw rope

he used in doing this was rotten, and gave way, precipitating him

below, where

he fell on the kinuta.4 He fractured his skull, and died

instantly. Asayo

and the actor, hearing the noise, went to see what had happened, and

were

rather pleased to find poor Yoichi dead. They did not report the death

until

next day, when they said that Yoichi had fallen downstairs and thus

killed

himself. They

buried him with indecent haste, and hardly with proper respect. Yoichi

having no children, his property, according to the Japanese law, went

to his

bad wife, and only a few months passed before Asayo and the actor were

married.

Apparently they were happy, though none in the village of Kumeda had

any

sympathy for them, all being disgusted at their behaviour to the poor

blind

shampooer Yoichi. Months

passed by without event of any interest in the village. No one bothered

about

Asayo and her husband; and they bothered about no one else, being

sufficiently

interested in themselves. The scandal-mongers had become tired, and,

like all

nine-day wonders, the history of the blind amma, Asayo, and Tamataro

had passed

into silence. However,

it does not do to be assured while the spirit of the injured dead goes

unavenged. Up in

one of the western provinces, at a small village called Minato, lived

one of

Yoichi's friends, who was closely connected with him. This was Okuda

Ichibei.

He and Yoichi had been to school together. They had promised when

Ichibei went

up to the north-west always to remember each other, and to help each

other in

time of need, and when Yoichi had become blind Ichibei came down to

Kumeda and

helped to start Yoichi in his business of amma, which he did by giving

him a

house to live in — a house which had been bequeathed to Ichibei. Again

fate

decreed that it should be in Ichibei's power to help his friend. At

that time

news travelled very slowly, and Ichibei had not immediately heard of

Yoichi's

death or even of his marriage. Judge, then, of his surprise, one night

on awaking,

to find, standing near his pillow, the figure of a man whom by and by

he

recognised as Yoichi! 'Why,

Yoichi! I am glad to see you,' he said; 'but how late at night you have

arrived! Why did you not let me know you were coming? I should have

been up to

receive you, and there would have been a hot meal ready. But never

mind. I will

call a servant, and everything shall be ready as soon as possible. In

the

meantime be seated, and tell me about yourself, and how you travelled

so far.

To have come through the mountains and other wild country from Kumeda

is hard

enough at best; but for one who is blind it is wonderful.' 'I am

no longer a living man,' answered the ghost of Yoichi (for such it

was). 'I am

indeed your friend Yoichi's spirit, and I shall wander about until I

can be

avenged for a great ill which has been done me. I have come to beg of

you to

help me, that my spirit may go to rest. If you listen I will tell my

story, and

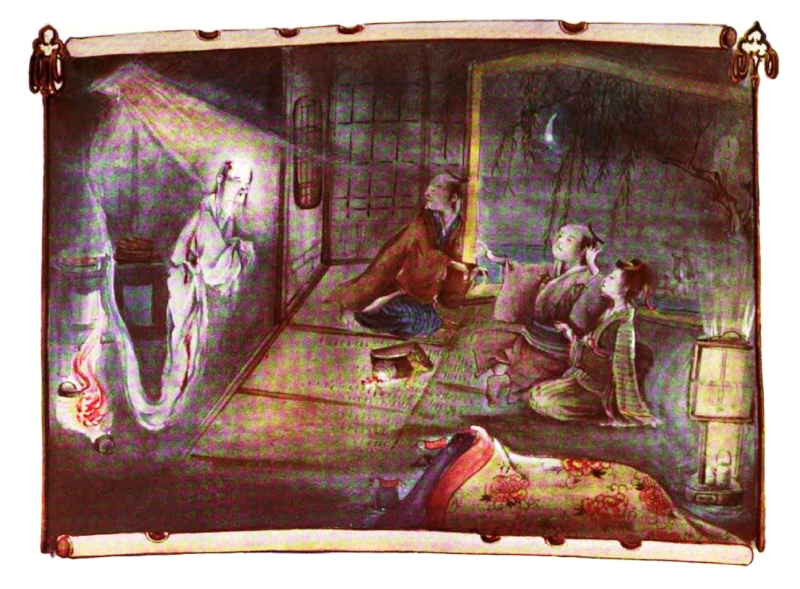

you can then do as you think best.' Ichibei

was very much astonished (not to say a little nervous) to know that he

was in

the presence of a ghost; but he was a brave man, and Yoichi had been

his

friend. He was deeply grieved to hear of Yoichi's death, and realised

that the

restlessness of his spirit showed him to have been injured. Ichibei

decided not

only to listen to the story but also to revenge Yoichi, and said so. The

ghost then told all that had happened since he had been set up in the

house at

Kumedamura. He told of his success as a masseur; of how he had saved

the life

of Asayo, how he had taken her to his house and subsequently married

her; of

the arrival of the accursed acting company which contained the man who

had

ruined his life; of his own death and hasty burial; and of the marriage

of

Asayo and the actor. 'I must be avenged. Will you help me to rest in

peace?' he

said in conclusion. Ichibei

promised. Then the spirit of Yoichi disappeared, and Ichibei slept

again. Next

morning Ichibei thought he must have been dreaming; but he remembered

the

vision and the narrative so clearly that he perceived them to have been

actual.

Suddenly turning with the intention to get up, he caught sight of the

shine of

a metal flute close to his pillow. It was the flute of a blind amma. It

was

marked with Yoichi's name. Ichibei

resolved to start for Kumedamura and ascertain locally all about

Yoichi. In

those times, when there was no railway and a rickshaw only here and

there,

travel was slow. Ichibei took ten days to reach Kumedamura. He

immediately went

to the house of his friend Yoichi, and was there told the whole history

again,

but naturally in another way. Asayo said: 'Yes:

he saved my life. We were married, and I helped my blind husband in

everything.

One day, alas, he mistook the staircase for a door, falling down and

killing

himself. Now I am married to his great friend, an actor called

Tamataro, whom

you see here.' Ichibei

knew that the ghost of Yoichi was not likely to tell him lies, and to

ask for

vengeance unjustly. Therefore he continued talking to Asayo and her

husband,

listening to their lies, and wondering what would be the fitting

procedure. Ten

o'clock passed thus, and eleven. At twelve o'clock, when Asayo for the

sixth or

seventh time was assuring Ichibei that everything possible had been

done for

her blind husband, a wind storm suddenly arose, and in the midst of it

was

heard the sound of the amma's flute, just as Yoichi played it; it was

so

unmistakably his that Asayo screamed with fear. At

first distant, nearer and nearer approached the sound, until at last it

seemed

to be in the room itself. At that moment a cold puff of air came down

the

tem-mado, and the ghost of Yoichi was seen standing beneath it, a cold,

white,

glimmering and sad-faced wraith. Tamataro

and his wife tried to get up and run out of the house; but they found

that

their legs would not support them, so full were they of fear. Tamataro

seized a lamp and flung it at the ghost; but the ghost was not to be

moved. The

lamp passed through him, and broke, setting fire to the house, which

burned

instantly, the wind fanning the flames. Ichibei

made his escape; but neither Asayo nor her husband could move, and the

flames

consumed them in the presence of Yoichi's ghost. Their cries were loud

and

piercing. Ichibei

had all the ashes swept up and placed in a tomb. He had buried in

another grave

the flute of the blind amma, and erected on the ground where the house

had been

a monument sacred to the memory of Yoichi. It is known as FUEZUKA NO KWAIDAN.5

_________________________________________

1 Told to me

by Fukuga. 2 Shampooer. 3 Hole in the

roof of a Japanese house, in place of a chimney.

4 A hard block

of wood used in stretching cotton cloth. 5 The flute

ghost tomb. |