| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2021 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Ancient Tales and Folk-Lore of Japan Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

| A STORY OF MOUNT KANZANREI FAR

up on the north-eastern coast of Korea is a high mountain called

Kanzanrei, and

not far from its base, where lies the district of Kanko Fu, is a

village called

Teiheigun, trading in little but natural products such as mushrooms,

timber,

furs, fish, and a little gold. In

this village lived a pretty girl called Choyo, an orphan of some means.

Her

father, Choka, had been the only merchant in the district, and he had

made

quite a fortune for those parts, which he had left to Choyo when she

was some

sixteen summers old. At

the foot of the mountain of Kanzanrei lived a woodcutter of simple and

frugal

habits. He dwelt alone in a broken-down hut, associated with but the

few to

whom he sold his wood, and was considered generally to be a morose and

unsociable

man. The 'Recluse' he was called, and many wondered who he was, and why

he kept

so much to himself, for he was not yet thirty years of age and was

remarkable

for his good looks and strong frame. Sawada Shigeoki was his name, but

the

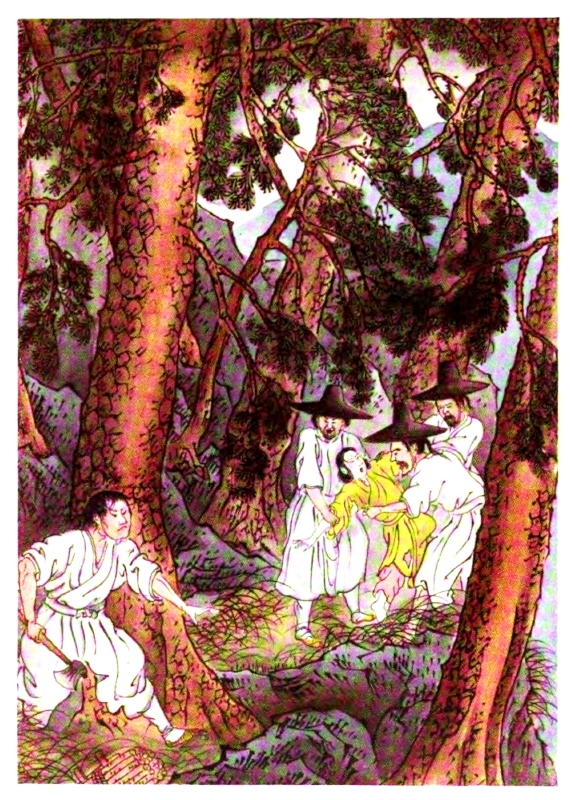

people did not know it. One evening, as the Recluse was wending his way down the rough mountain path with a large load of firewood on his back, he was resting in a particularly wild and rocky pass darkened by the huge pine trees which towered on every hand, and was startled by a rustling sound close below. He looked nervously round, for the place in which he was had the reputation of being haunted by tigers, and with some truth, for several people had lately been killed by them. On this occasion, however, the sound which had startled the Recluse was caused by no tiger, but only by a pheasant which fluttered off her nest, and was imitating the sign of a wounded bird, to draw the intruder's attention away from the direction of her nest. Strange, however, was it, thought the Recluse, that the bird should have so acted, for she could neither have seen nor heard him; and so he listened intently to find the cause. There were not many minutes to wait. Almost immediately the Recluse heard the sounds of voices and of scuffling, and, hiding himself behind the trunk of a large tree, he waited, axe in hand.  The Woodcutter Saves Choyo From Robbers Soon

he saw being carried, pushed, and dragged down the path, a girl of

surpassing

beauty. She was in charge of three villainous men whom the Recluse soon

recognised as bandits. As

they were coming his way the Recluse retained his position, hidden

behind the

great pine, and grasping more firmly his axe; and as the four

approached him he

sprang out and blocked their way. 'Who

have you here, and what are you doing with this girl?' cried he. 'Let

her go,

or you will have to suffer!' Being

three to one, the robbers were in no fear, and cried back, 'Stand out

of our

way, you fool, and let us pass — unless you wish to lose your life.'

But the

woodcutter was not afraid. He raised his axe, and the robbers drew

their

swords. The woodcutter was too much for them. In an instant he had cut

down one

and pushed another over the precipice, and the third took to his heels,

only

too glad to get away with his life. The

Recluse then bent down to attend to the girl, who had fainted. He

fetched water

and bathed her face, bringing her back to her senses, and as soon as

she was

able to speak he asked who she was, whether she was hurt, and how she

had come

into the hands of such ruffians. Amid

sobs and weeping the girl answered: 'I am

Choyo Choka. My home is the village of Teiheigun. This is the

anniversary of my

father's death, and I went to pray at his tomb at the foot of Gando

Mountain.

The day being fine, I decided to make a long tour and come back this

way. About

an hour ago I was seized by these robbers; and the rest you know. Oh,

sir, I am

thankful to you for your bravery in saving me. Please tell me your

name.' The

woodcutter answered: 'Ah,

then, you are the famous beauty of Teiheigun village, of whom I have so

often

heard! It is an honour indeed to me that I have been able to help you.

As for

me, I am a woodcutter. The "Recluse" they call me, and I live at the

foot of this mountain. If you will come with me I will take you to my

hut,

where you can rest; and then I will see you safely to your home.' Choyo

was very grateful to the woodcutter, who shouldered his stack of wood,

and,

taking her by the hand, led her down the steep and dangerous path. At

his hut

they rested, and he made her tea; then took her to the outskirts of her

village, where, bowing to her in a manner far above that of the

ordinary

peasant, he left her. That

night Choyo could think of nothing but the brave and handsome

woodcutter who

had saved her life; so much, indeed, did she think that before the morn

had

dawned she felt herself in love, deeply and desperately. The

day passed and night came. Choyo had told all her friends of how she

had been

saved and by whom. The more she talked the more she thought of the

woodcutter,

until at last she made up her mind that she must go and see him, for

she knew

that he would not come to see her. 'I have the excuse of going to thank

him,'

she thought; 'and, besides, I will take him a present of some

delicacies and

fish.' Accordingly,

next morning she started off at daybreak, carrying her present in a

basket. By

good fortune she found the Recluse at home, sharpening his axes, but

otherwise

taking a holiday. 'I

have come, sir, to thank you again for your brave rescue of myself the

other

day, and 1 have brought a small present, which, I trust, however

unworthy, you

will deign to accept,' said the love-sick Choyo. 'There

is no reason to thank me for performing a common duty,' said the

Recluse; but

by so fair a pair of lips as yours it is pleasing to be thanked, and I

feel the

great honour. The gift, however, I cannot accept; for then I should be

the

debtor, which for a man is wrong.' Choyo

felt both flattered and rebuffed at this speech, and tried again to get

the

Recluse to accept her present; but, though her attempts led to friendly

conversation and to chaff, he would not do so, and Choyo left, saying: 'Well,

you have beaten me to-day; but I will return, and in time I shall beat

you and

make you accept a gift from me.' 'Come

here when you like,' answered the Recluse. 'I shall always be glad to

see you,

for you are a ray of light in my miserable but; but never shall you

place me

under an obligation by making me accept a gift.' It

was a curious answer, thought Choyo as she left; but 'Oh, how handsome

he is,

and how I love him! and anyway I will visit him again, often, and see

who wins

in the end.' Such

was the assurance of so beautiful a girl as Choyo. She felt that she

must

conquer in the end. For

the next two months she visited the Recluse often, and they sat and

talked. He

brought her wild-flowers of great rarity and beauty from the highest

mountains,

and berries to eat; but never once did he make love to her or even

accept the

slightest present from her hands. That did not deter Choyo from

pursuing her

love. She was determined to win in the end, and she even felt that in a

way

this strange man loved her as she loved him, but for some reason would

not say

so. One

day in the third month after her rescue Choyo again went to see the

Recluse. He

was not at home: so she sat and waited, looking round the miserable hut

and

thinking what a pity it was that so noble a man should live in such a

state,

when she, who was well off, was only too anxious to marry him; — and of

her own

beauty she knew well. While she was thus musing, the woodcutter

returned, not

in his usual rags, but in the handsome costume of a Japanese samurai,

and

greatly astonished was she as she rose to greet him. 'Ah,

fair Choyo, you are surprised to see me now as I am, and it is also

with sorrow

that I must tell you what I do, for I know well what is in both your

heart and

mind. To-day we must part for ever, for I am going away.' Choyo

flung herself upon the floor, weeping bitterly, and then rising, said,

between

her sobs: 'Oh, now, this cannot be! You must not leave me, but take me

with

you. Hitherto I have said nothing, because it is not for a maid to

declare her

love; but I love you, and have loved you ever since the day you saved

me from

the robbers. Take me with you, no matter where; even to the Cave where

the

Demons of Hell live will I follow you if you will but let me! You must,

for I

cannot be happy without you.' 'Alas,'

cried the Recluse, 'this cannot be! It is impossible; for I am a

Japanese, not

a Korean. Though I love you as much as you love me, we cannot be

united. My

name is Sawada Shigeoki. I am a samurai from Kurume. Ten years ago I

committed

a political offence and had to fly from my country. I came to Korea

disguised

as a woodcutter, and until I met you I had not a happy day. Now our

Government

is changed and I am free to return home. To you I have told this story,

and to

you alone. Forgive my heartlessness in leaving you. I do so with tears

in my

eyes and sorrow in my heart. Farewell!' So saying, the 'brave samurai'

(as my raconteur

calls him) strode from the hut, never to see poor Choyo again. Choyo

continued to weep until darkness came on and it was too late for her to

return

home in safety: so she spent the night where she was, in weeping. Next

morning

she was found by her servants almost demented with fever. She was

carried to

her home, and for three months was seriously ill. On her recovery she

gave most

of her money to temples, and in charity; she sold her house, keeping

only

enough money to buy herself rice, and spent the remainder of her days

alone in

the little hut at the foot of Mount Kanzanrei, where at the age of

twenty-one

she was found dead of a broken heart. The samurai was brave; but was he

noble

in spite of his haughty national pride? To the Japanese mind he acted

as did

Buddha when he renounced his worldly loves. What chance is there, if

all men

act thus, of a sincere friendship between Japan and Korea? |