| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| "When icicles hang by the wall, And Dick the shepherd blows his nail, And Tom bears logs into the hall, And milk comes frozen home in pail." Shakespeare. THE best time to begin to study birds is, for several reasons, the season when they are to be found not most but least frequently. In the annual circuit of bird-life we shall find that winter is the true chronological starting-point, and on other accounts, which will immediately appear more forcible to the beginner, the new year is of all times the most favorable for his first essays in this new pursuit, whether the study be undertaken as a mere diversion or with more serious intent. At this season there is not such a variety of species as to confuse one who has not learned what to look for, nor how properly to look for it. An adept will often gather at a glance enough of the distinctive marks of an unfamiliar species to enable him to identify it fully; while the novice would only be bewildered, and not knowing how to look at the specimen discriminatingly, would fail of seeing anything distinctly. A few weeks of effort in this and in all kindred pursuits bring very forcibly to the mind of the beginner the truth of the old couplet And sight, who had but eyes before." A good opera-glass is an indispensable companion in one's researches, and it is not amiss to suggest that he cannot too quickly conquer his diffidence in using the glass freely, even though it attract the curious attention of people about him. I have lost many a good view of a bird I wanted to see, through dislike of the gaping looks of an idle passer-by. Without approaching a bird as closely as would be necessary without a glass, you avoid frightening it away, and can have a much longer view; for a bird is always keenly alert with eye and ear to discover any one's approach, but they are sharp enough to know there is less danger from a mere passer-by, however boisterous, than from one who suspiciously loiters about in the vicinity. It is as amusing as it is exasperating to see how quickly they sometimes detect your purpose. Having discovered a specimen, it requires a little practice to bring the glass to bear instantly on the precise point; and if not done at once, the bird is likely to be so disobliging as to change its position, and you will run the risk of losing it altogether. It is advisable to gain facility in this matter by fixing the eye on some remote but distinct object, like the end of a branch, and learning to cover it instantly with a glass. The opportunities of seeing specimens are too valuable to be wasted in such practice. The absence of foliage in winter makes a vast difference in the ease of discovering birds, and of following their motions as they go from tree to tree. A delicate aspen-leaf can hide a warbler, and any of the larger song-birds can be lost behind a leaf of maple or of oak, while the plumage often blends confusingly with the foliage. In the case of the sparrows, which are peculiarly ground-birds, it has been ingeniously suggested that their prevailing neutral colors prove them to be the "survival of the fittest" to escape the sharp eyes of their various enemies, all the brighter-colored species (if there ever were any) having been gradually exterminated. In the construction of their nests, too, it is often evident that birds feel the necessity of eluding observation, not only by placing them in concealment, but by making the exterior of the nest so harmonious in color and texture with its surroundings, that it is sometimes scarcely discernible even when close before your eyes. It often seems as if the chronic anxiety and ceaseless vigilance of these creatures to escape destruction would make life hardly worth living. Even in winter,"When there is a hush of music on the air," you

commonly hear a chirp or zip before you see the bird, and not

infrequently these call-notes are distinctive enough to indicate the

species. This is perhaps especially true of the winter birds, when

the various families are represented by so few species, and the

more remote the relationship the more unlike the notes are

likely to be. For example, the white-throated sparrow has a peculiar

and unmistakable tone, soft, but shrill, as unlike that of the

cardinal grosbeak or of the nuthatch as possible, although not easily

distinguished from the note of some of the species appearing later in

the season. Indeed, without these faint suggestions of their presence

there could hardly be any such thing as winter ornithology, as the

naturalist relies so much more on his ear than on his eye to discover

them.

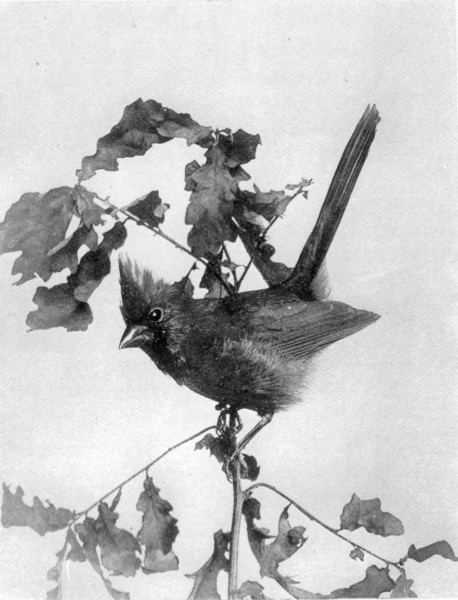

The "white-throat" is one of the prettiest species of sparrows (whose merit, as a class, is not that of good looks), apparently quite numerous in this region in winter, and can be seen any day in the Park. The head is very distinctly striped with black, white, and a bit of yellow, while the throat is conspicuously white. The rest of the body is rather neutral in color. They are commonly found on the ground or in bushes, rarely flying to any great height in trees, and at this season always seem busily engaged in picking up a very precarious living. We are told they neither reap nor gather into barns. In fact, like all others of the feathered race, they live very much from hand to mouth. This trait, so reprehensible in the human family, gives the birds many a solid day's work in the snows of winter, trying to satisfy the pangs of hunger, which are not always satisfied even then. After a fresh fall of snow covering the usual sources of supply, I have found the "white-throats" busily exploring the bushes after sundown on a cold January night. But whether they feast or fast, they remain careless and happy, which is fortunate and perhaps commendable. Yet nature is not so unskilful nor unkind, after all, as at first appears; for both birds and beasts are a storehouse unto themselves, in the mass of adipose matter snugly stored up under their skins, as a supply of fuel with which to maintain their winter fires. Without this wise provision of nature countless numbers must inevitably perish during the stress of winter, and very many do as it is. The leanness with which many wild animals appear in the spring shows how thoroughly they have exhausted their reserve force. The best time of day to look for birds the year round, with some few exceptions, is in the forenoon, and in a cold winter's day not till ten or eleven o'clock, for at this season they rise late and retire very early. They pick up an abundant breakfast (if possible), and with a full stomach their activity ceases. They will then remain perched in some protected spot, until gastronomic cravings again drive them forth. A spot protected from the wind and exposed to the sun is a common rendezvous in winter, and I have noticed that a high wind disturbs their equanimity and drives them to shelter fully as much as intense cold. With no other occupation than their precarious purveyance, and amid the most cheerless surroundings, if they were obliged to think all winter, it would indeed be a most tedious and disheartening experience for them. Probably no mere animal has any of a human being's sense of the lapse of time, for which they cannot be too profoundly grateful. One of the daintiest species to be found in the woods at this season, a spark of vital warmth in the surrounding cold, is the golden-crowned kinglet, also called golden-crowned wren, or "gold-crest." This little creature is less than five inches long (a bird's length being measured from the tip of the bill to the end of the tail), and its head is beautifully marked with two black stripes enclosing a yellow stripe which in the mature male has a scarlet centre. The rest of the body is in the main greenish olive above, and an impure white beneath. It is impossible to get a good view of all these points at once, as he is in almost perpetual motion, nimbly hopping from spot to spot in the bushes and trees, and fluttering his wings. His food at this season is chiefly the larvæ of insects that lie concealed in the bark. Either from that sense of security that comes only from irreproachable morals or manners, or because he is really too busy to take notice of other people, he is very easy to approach. When you find one, you may be sure there are others not far away, as they are gregarious at this season of the year. They make a merry company as they explore the trees together, and their soft but musical zee, zee, zee, and sprightly manners seem unmistakable evidence that they are in the best of spirits. They are very plentiful hereabouts, for scarcely a day passes that I do not see them, and they are so incessantly lively that it seems hardly possible that they can sleep longer than during the winks. They are only winter-birds in this region, summering and breeding in the White Mountains, northern Maine and beyond, so that they are with us only from October to April, or a little later. One feature of the winter-birds, viz., their song, can of course only be known by the reports of those who hear them in their summer homes. That of the kinglet is said to be "a series of low, shrill chirps, terminating in a lisping warble." Its congener, the ruby-crowned kinglet, is a much finer vocalist. The various species are quite different, as regards their habits of association. Some, like the kinglets, are gregarious in winter, and much less so in summer; others, like the robin, are so the year round; some, like the brown creeper, associate with other species, and very little with their own; others are found in pairs, and some live a very isolated life. The longer one studies the birds, especially as regards their habits, the more pronounced become their individualities in his mind. Their traits of character are revealed by their manners, and not by their plumage, and this is what makes a collection of stuffed specimens so utterly meaningless. Their various tints count for no more than so much paint, and are as expressionless as a rainbow. Many a handsome specimen excites only the admiration of color, while a plain little song sparrow can endear itself to every beholder. I am aware that my estimate of some of the birds differs from that of other ornithologists. Very likely they are right and I am wrong. Still, as second-hand opinions, even of birds, are poor property, it is better and more honest to maintain one's own, when held for a cause, reserving the right to change for good reason, as one would do in regard to any of his other friends. An inoffensive but wearisome little fellow is a brown-clad denizen of all our woods in winter, and commonly found not far away from the kinglets and chickadees, viz., the brown creeper, almost invariably seen on the trunks of trees whose bark is somewhat rough, as the smooth surface of other trees affords no hiding-place for the larvæ on which he subsists. He is a little over five inches long, white beneath, and finely marked with various shades of brown and white above. On first acquaintance it makes no particular impression other than that of being a neatly clad and busy little body; but in course of time it becomes really irritating to the feelings, from its exasperatingly conscientious but cold-blooded diligence, which makes you feel as if you ought to admire it on moral grounds; but you cannot. In fact, too much conscience gets to be monotonous. The brown creeper is a virtuous drudge, without animation or variation. There is an air about him, as he silently climbs tree after tree, that makes his work seem as soulless as it is incessant. When you have seen it a minute you have seen it a year, and seeing one is seeing a thousand. He starts near the bottom of a tree, crawls up just about so fast and so far, and then flies to the bottom of another, only to repeat the programme. By close application to business (and nothing but sickness can stop him) I find he can do a tree in just about fifty seconds, or seventy-two trees in an hour, and in the twenty-four hours (as far as I know he works nights and Sundays) seventeen hundred and twenty-eight trees. If he would only sing or chirp at his work, or flutter his wings, or turn his head occasionally, it would change the impression marvellously. Only now and then you hear a faint sip, that cheers neither himself nor the spectator, and has a drearily mechanical and conscientious sound. Every other bird I have seen will at times show joy or sorrow or fear by its manner or song, but the creeper has only one aim and ambition, and no time for sentiment. If in the transmigration of souls Sisyphus was ever incarnated in bird-form, we certainly have him here, neatly encased in feathers, for it is nothing but climb, climb, climb, and never getting there. One of the thousand evidences of nature's grand consistency is shown by the conformity of color in the plumage of birds with the prevailing tone of the landscape. The arctic birds are largely white, those of the tropics brilliant hued, and in our own clime the richly tinted species appear amid the bloom and verdure of spring and summer; while the snow and the sombre tints of the winter landscape are matched by the whiteness of the sea-gulls, the mingled black and white of snow-bird, chickadee, and downy woodpecker, the brown and white of the snow-bunting, and the browns of the flicker, goldfinch, and creeper. Yet the jewel of consistency is not tarnished but enhanced by nature's occasional departure from the severity of her own laws, showing them to be curvilinear rather than angular. A delightful surprise it is, therefore, to find in the Park, at this season, a flock of cardinal grosbeaks, also called red-bird and Virginia nightingale, of graceful form, rich in color, and of rather lordly air with their prominent crests, apparently living a comfortable life in a climate that would seem too severe for their more tropical natures. They are a little smaller than the robin, the male a bright vermilion, black about the bill, while the bill itself, which is large and prominent, is bright coral red. A stuffed specimen gives no idea of its beauty, as the color so quickly fades after death. When

not feeding from the berries that

still cling to the trees, they condescend to patronize the "board"

spread by the Park officials for all the feathered tribe, and for the  Cardinal Grosbeak

instant

mingle with the more plebeian

sparrows and pigeons. Their call-note is loud, musical, and

characteristic, leading one to expect much when they come into

full song. Compared with the ever-busy kinglets they live a life of

elegant ease; and indolence best comports with aristocratic airs. As

their summer residence is mostly in the Southern States, their

occurrence in winter so far north as New York is quite exceptional.

But one must not always keep his eyes on the ground, or exploring the shrubbery and trees, if he would see all that a winter's day affords. High in the air, their pure white pinions clearly outlined against the deep blue, you can often see the gulls, either singly or in small flocks, that are found along the coast and inland at this season. The commonest species seen hereabouts in winter is the herring-gull, which, as the warm weather approaches, retires to its breeding-grounds along the seashore from Maine to Labrador. The pearly mantle that covers the back can only be seen as it now and then skims the surface of the water, or rests awhile on the waves from which it gathers its food. But the air seems their native element more than the water, and in the grand sweep of their wings and in their slow and majestic progress, they give to the beholder the sense of rest rather than of weariness. It is a simple but necessary rule that if you would see the birds you must go where they are. In winter they chiefly frequent the evergreens and such other trees as have coarse bark in which the larvæ of insects are hid. They are also to be looked for among the shrubbery and weeds to which last year's berries and seeds are still clinging; while in the coldest weather they gather what cheer they can in some sheltered, sunny nook, where they find a brief respite from icy winds and chilling shadows. To them at this season certainly life is little more than meat. Knowing their habits helps very much to identify them. If you find a specimen curiously running around and up and down the tree-trunk, as if all directions were horizontal, it is inevitably the nuthatch — probably the white-breasted — though you may not have a glimpse of its bluish back and black collar. (Later in the year you will find two species of warblers reminding you of the nuthatch in their movements.) If it hugs the trunk and is always moving upward, either in straight lines or spirally, it is as certainly the brown creeper. Looking at this bird attentively you will see that its tail feathers are very stiff and sharp-pointed, and used as a means of propping itself as it ascends, which accounts for its always creeping upward. (The woodpeckers are larger, and have not the incessant motion of the creeper.) If, again, your specimen flies nimbly from twig to twig, and assumes all sorts of attitudes that would be grotesque if they were not consummately graceful, and above all, if a merry laugh rings out on the air as it busily explores the branches, then it is certainly the chick-adee-dee–dee. The different movements of these species are explained by the fact that while the nuthatch supports itself entirely by its claws inserted in the bark, and the brown creeper by its claws and tail, the chickadee grasps the slender twigs, and therefore moves among the higher and smaller branches, and never on the trunk. The nuthatch, about six inches long, and already sufficiently described for identification as to color and habits, commonly travels about in pairs, making its presence known by a loud and peculiar tone not unlike the syllable ank, and generally uttered twice; besides this it has a much softer note, and I have once heard a very melodious twitter as it quietly rested on a branch; but it can hardly be regarded as a song-bird, although classed among them. Neither can it be called graceful nor handsome, but its habits are especially interesting, and it gains the more regard from being associated in our mind with cold weather, for it disappears at the approach of spring, breeding much farther north. Wilson says: "The name Nuthatch has been bestowed on this family from their supposed practice of breaking nuts by repeated hatchings or hammerings with their bills;" but the same writer shows good reason for doubting the validity of the name. Of the woodpeckers, a family that is ungainly in form, but attractive in habits, I have seen only two species during the month; first, the downy woodpecker, about six inches long, and the smallest of the family, black and white curiously mingled, while the male has the distinguishing badge of a bright crimson patch on the hind-head. This species is very common throughout eastern North America in woods and orchards, and seems to be more desirous of proximity to man than the other species of the same family. Matrimonial arrangements are commonly made annually among the birds, but the "downies" are usually mated for life, and hence are often seen in pairs instead of singly. Neither are they so migratory as many others, and often remain in one locality throughout the year. The woodpeckers are not singers, but every species has its note, more or less shrill, and some of them have quite a variety of such notes. These sounds probably serve as means of communication among themselves, and perhaps relieve their overcharged feelings, as in the case of the pileated woodpecker, or log-cock, which, Minot says, "often produces a loud cackling, not wholly unlike that of a hen. Hence a countryman, asked by a sportsman if there were any of them in a certain place, answered that he often heard them hollering in the woods.' " The other woodpecker in the Park is the "flicker," alias "golden-winged woodpecker," alias "yellow-hammer." It has eleven other names, based on its habits or appearance. This is quite a large bird, over twelve inches long, of a curiously mottled brownish color above, whitish and black spotted beneath, with a black crescent on its breast and a scarlet crescent on the back of its head. In flight it is easily identified by the large white area on the lower part of the back or rump. The finest view of it is when it spreads its broad wings against the sunlight, for they are of a deep rich yellow inside, from which it gets the name of "golden-winged." Its variety of names shows its prevalence over an extensive area, being found from the Gulf of Mexico to Hudson's Bay. They are not in the fullest sense of the term woodpeckers, inasmuch as their food is largely gathered from the ground, consisting of ants and other insects, berries and grain, although at times showing the instinct of the true woodpecker in extracting insects, larvæ and eggs from the bark. Like the other species, they excavate their nests in the trees, and some of the accounts of their nest-building are very interesting. It has a very harsh, loud note, uttered singly, and another, softer and sweeter, often repeated rapidly a dozen times or more, which is hardly distinguishable from the call-note of the robin. It is found in this region the year round, but its presence in the Park is chiefly during the cold weather. Birds easily adapt themselves to circumstances; and, although I was brought up to believe that I should never, under any conditions, find doves alighting on trees, it is a common sight in the Park: probably due to the fact that there are scarcely any buildings in the vicinity; yet even such as there are they studiously avoid, always flocking to the maples and elms, as they were doubtless wont to do in their predomesticated state. There is no virility about a dove: just a mass of meat, feathers, and flabby good-nature; too inoffensive to be interesting; for an object that it is impossible to hate, it is impossible to love. As white is to black, so are doves to crows — a rather favorite fowl of mine, though as common as sin, of which it is a sort of winged symbol. Coarse-fibred, harsh-voiced, and villainous as it is, it is a broad and solid dash of color that could be ill spared in the landscape. How tersely and vividly descriptive those few words of Shakespeare: Makes wing to the rooky wood; " — a

simple and suggestive scene in the

gloaming, familiar to every one who has lived in the country. I

know that crows are held in general derision, that their hearts

are supposed to be of the same hue as their plumage, and only to be

frowned upon from both a moral and esthetic point of view. But I beg

leave to insert a line of protest in their favor, and candidly

confess that it is to me a peculiarly pleasurable sight to see them

coursing in their strong and dignified flight over the landscape; and

when an interval of a quarter of a mile has filtered out the most

rasping quality of the voice, the barbaric clamor of half a dozen

gossipy crows affords an unwonted delight. There is a wildness

in the sound that stirs the blood; it has a pungent, salty flavor

that the ear craves. Too much refinement takes away the vigor and

pith of a distant object, be it audible or visible, and there is more

of the sturdy country life in the crow than in a dozen songsters. The

slow and measured step with which they walk is called by Audubon

"elevated and graceful;" and as he is so illustrious and

dead, I will not presume to question the truth of the statement. They

are very gregarious throughout the year, and omnivorous rather than

fastidious in their diet, not only pillaging the grain-fields and

fruit-trees, but having a relish for insects, all kinds of flesh,

shell-fish, and the like, while their most vicious trait is the

destruction of the eggs and young of other birds. To estimate the

crow rightly, one must let admiration and contempt lie side by side

in his mind, without allowing either to neutralize the other.

The Park is not a favorable place for birds of prey, but it has harbored a hawk for several weeks this winter. The larger and longer-lived birds are correspondingly slow in coming to maturity, and until they reach that stage identification is difficult and often impossible from the plumage. From its rather nondescript coloring, this specimen seemed to be immature. Gliding silently through the trees, like a spirit of evil, it eluded a near approach, and at last disappeared altogether. There is something spectral and malevolent in the demeanor and solitary life of the birds of prey that is of peculiar interest. Standing in no possible relation of human sympathy, they prove attractive in part by the very qualities that are repellent, presenting an aspect of bird-life as strange as it is fascinating. One day, in passing some shrubbery, a faint and rather dolorous chirp called my attention to a song sparrow quietly perching; but in that cold winter's day there was no song in its heart, and it was patiently biding its time. Farther on I stumbled upon a catbird, which is quite out of place here at this season. It was too much occupied in picking over the dead leaves in search of food to take much notice of my intrusion; but having sufficiently canvassed the ground, it flew away, and I did not find another till April. For those who may be unfamiliar with this degenerate scion of the noblest family of birds (the thrushes) it may be remarked that it is a little shorter than the robin, of a slate color, crown and tail black, while the under tail-coverts (covering the base of the tail) are chestnut-red. Another friend in the Park is a little specimen, common in winter from New England to Florida, and so fearless as often to be found about the houses and barns in the country — the snow-bird, a trim and sprightly creature about six inches long, dark slate above and on the breast, which passes very abruptly into white beneath, as if it were reflecting the leaden skies above and the snow below. It is commonly seen on the ground, in shrubbery, or the lower branches of trees, and, with a large measure of confidence in human nature, it yet discreetly flies on a little in advance as you approach. It has a vivacious, tinkling note, quite distinct from any other winter bird. Although the snow-birds are here all winter, they become more numerous at the approach of spring. They have a conspicuously sociable disposition, and mingle freely with sparrows, chickadees, and the early migrants. Their sleek and natty appearance and genial temper commend them at once to the observer. The

foregoing list of birds found in

the Park, during what is perhaps the most unpropitious month of the

year — the white-throated sparrow, kinglet, brown creeper,

nuthatch, chickadee, song sparrow, downy woodpecker, golden-winged

woodpecker, hawk, catbird, cardinal grosbeak, gull, crow and

snow-bird, — comprises those which one is most likely to meet in

all our woods, during the winter; not a remarkably long list,

but more extended than an unobservant person would suppose, and

affording objects

of search and thought that can

render a walk, even through the bleak woods in winter-time, a source

of instruction and pleasure.

Snow Birds

Of course no self-respecting ornithologist will condescend to enlarge his list by counting in the pigeon and the English sparrow; the former not being wild game, and the latter too pestiferous for mention. |