|

(Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Cambridge Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

During the early part of the reign of Charles I "the University", says Fuller, "began to be much beautified in buildings, every College either shedding its skin with the snake, or renewing its bill with the eagle, having their courts or at leastwise their fronts and gatehouses repaired and adorned. But the greatest alterations were in their chapels, most of them being graced with the accession of organs." Many of the chapel ornaments were subsequently defaced by Cromwell; but, as has already been stated, King's was left untouched in the matter of its fabric, its glass, and its brasses. The elaborate .tombs in Caius Chapel were not injured; and the much earlier tomb – that of Hugh Ashton – in St. John's was also left undisturbed. The Fellows of Peterhouse took the precaution to bury the glass which filled the east window of their chapel. It lay undiscovered, and all of it has now been replaced. Certainly Cromwell got some plate out of the University, but this tribute was as nothing when compared to that which went to Charles. Trinity sent practically its all. King's, as the earlier Royal Foundation, could not afford to be behindhand. St. John's was Tory almost to a man, and away went most of her finest silver. "Her contribution", says the present Master, "was £150 in money and 2065 ounces, grocer's weight, of silver plate." Among the pieces so lost were some bearing the names of Thomas Wentworth, Lord Strafford, and of Thomas Fairfax. For this the College later suffered much indignity. Cromwell surrounded the place, took the Master a prisoner, and "confiscated the communion plate and other valuables". Nearly every College had paid tribute; but the fact that Cambridge was providentially spared the duty of nursing, either then or afterwards, any part of a Stuart Court, enabled her to save for posterity as much in gold and silver works of handicraft as Oxford lost. Thus the Cambridge plate as it stands to-day is the finest collection of its kind in existence. Throughout these two hundred years – years of Renaissance, of Reformation, of Revival, of Revolution – Cambridge poured forth an unending stream of men destined for the highest places in church, in state, in scholarship, and in letters. Coverdale, Fox, Ridley, Latimer, Cranmer, Gardiner, Parker, Grindal, Whitgift, Bancroft, Andrews, Cosin, Williams, Taylor, Stillingfleet, Sancroft, Tillotson, Tenison are her divines; and of the seven "nonjuring" bishops, five, including the Primate, were Cambridge men. The Protector Somerset, Cecil the great Lord Burleigh, his kinsman of Salisbury, Walsingham, Essex, Fulke Greville, Sir John Harrington, Chief Justice Coke, Sir Nicholas Bacon and his son Francis, Lord Verulam (commonly but wrongly styled Lord Bacon), Sir William Temple, Oliver Cromwell are figures which are painted large upon the canvas of history; and in a dark corner are inscribed the names, at once famous and infamous, of judge Jeffreys and Titus Oates. The lists of Cambridge scholars, poets, and prose writers of this age is no less remarkable. Roger Ascham, Sir John Cheke, Sir Thomas Smith, Jeremy Taylor, Thomas Fuller; the poets Spenser, Harvey, Marlowe, Greene, Fletcher, Ben Jonson, Heywood, Andrew Marvell, Milton, Cowiey, Donne, Dryden, Herbert, Herrick, are names likely to live so long as the English language be spoken. Among Cambridge antiquaries we find the names of Stowe, Leland, and Strype. In medicine Cambridge was the foremost English school, and the names of Caius, Butler, Gilbert, and Harvey have a permanent place in the history of that Faculty. Three celebrated men of letters – Shirley, Lodge, and Lilley – migrated from Oxford to Cambridge. Wolsey, when he founded in Oxford his Cardinal's College – now styled Christ Church – came to King's College and King's Hall in Cambridge for many of his first Fellows. A Cambridge College, Pembroke, gave no fewer than four Heads to Oxford Houses during the latter half of the sixteenth century; and of this same College was Bishop Fox, the founder of Corpus Christi College in Oxford, and of two professorships there. In the New World, with the names of "the Pilgrim Fathers", are remembered those of Hooker of Peterhouse, of Eliot the "Indian Apostle" who took his degree in 1622, and of John Harvard of Emmanuel, the founder of America's oldest House of Learning. Horrocks and Flamsteed, the astronomers, founded a Cambridge School of Astronomy which has since taken the foremost place in the development of that science. The Cambridge of our own day contains much that is reminiscent of those two hundred years. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries academical dress settled itself into the form in which for the most we now see it. But something has come down to us of even earlier days. Cambridge is not unjustly proud of the fact that, unlike Oxford, the shape of its hood has remained practically unaltered since the fourteenth century. A notable mediaeval garment still worn at Cambridge, and not elsewhere to be found, is the Cappa Clausa or "closed cope", used by the Vice-Chancellor and by certain Doctors of Divinity, Law, and Physic on special occasions. It is of scarlet cloth with an ermine hood and trimmings. It must not be confused with the scarlet gowns worn by all doctors in the several Faculties on gala days. Over the gate of Queens' College the curious may see a rude representation of a doctor so robed; but a really fine example of this dress as worn in the sixteenth century may be seen on the brass to the memory of John Argentein, D. D., M. D. (1507), in King's College Chapel. It was during the sixteenth century that the present style of M.A. gown and that of the Law gowns worn at Cambridge by Doctors of Laws and in the Courts by King's Counsel came into use. The style is fundamentally that of the ordinary walking dress of a notable of the end of the fifteenth century. A robe of this kind, as an over-garment, obtained all over Europe during the succeeding hundred years, and it would appear to have been Italian in origin. An example of the academical form of this garment may be seen on a brass at Croxton in Cambridgeshire, where is represented the figure of one Edward Leeds, LL.D., a Master of Clare Hall, who died in 1589. The strings now worn on all Cambridge gowns would seem to have come into general use about this time. In early times gowns were "closed" garments, and were put on over the head; and after it became lawful to wear them open in front, strings were used to tie the gown across the breast, and they were so worn until quite recently. Three other survivals of the costume of this later period may be noted. They are all peculiar to Cambridge. For example, the Proctor assumes on certain occasions an upper garment called a "ruff". Over this he wears his hood in the ordinary way. On certain other occasions, however, he must wear his hood "squared", that is, so folded that it presents the appearance of a large square cape. The method of arranging this dress has been handed down, as has a pattern "ruff", from Proctor to Proctor; but nowadays the repositories of such traditions are more often the Proctors' men, who, in these matters, perform the offices which judges expect of their clerks. The full dress of a Proctor's man – or "bull dog", as he is vulgarly called-is picturesque enough, for it is of a seventeenth-century pattern and consists in a long blue cloak studded with brass buttons. With this he carries a halberd. The Chancellor or Vice-Chancellor in procession is always preceded by two graduates, of M.A. standing at least, who are styled Esquire Bedells. The maces which these gentlemen carry on such occasions were given by George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, the favourite of James I. The Duke was elected Chancellor of the University by the narrow majority of five votes. Another old custom, full of associations for Cambridge men, is the ringing of Curfew at Great St. Mary's Church. The University bell rings the Curfew nightly from nine of the clock till ten minutes past the hour. The date of the month is also struck by one of the same peal of bells. More curious, however, is the fact that the service, or, more properly speaking, the "office" of Compline, is commemorated at Trinity Hall by the ringing of a bell there nightly at ten o'clock.

Many echoes of those "Disputations" which in mediaeval times took the place of examinations may be followed in the Cambridge of to-day. The office of "Moderator" is with us still; Junior and Senior "Sophisters" are those who are on the road to becoming "Questionists"; and "Wranglers" are those who issue with honours from the supposed contest. A person qualifying for a medical degree when reading or submitting his finished "Thesis" is said to "Keep an Act" (i.e. a Disputation) for that degree. The origin of the word Tripos is not yet settled. Perhaps it derived itself from some sort of stool. Anyhow, by the middle of the eighteenth century, the Tripos had come to mean a sheet of paper upon one side of which were printed the names of those who had attained Honours in the Mathematical School, whilst upon the other was a copy of Latin Verses. Sheets of this Tripos paper were thrown by the Moderators from the gallery of the Senate House into the crowd assembled below. But until this same century was some way advanced another set of verses, usually very scurrilous in character, were recited by a sort of University Buffoon, who came also to be called "The Tripos". Licensed revellers were well-known institutions in both Universities throughout the Middle Age; but it was not until this Tripos fellow had been the subject of many scandals, protests, and warnings, that he was finally abolished. The history of the English Universities in the eighteenth century has yet to be written; and though much material for such a history is accessible to the humblest enquirer, it is not possible in so short an essay as the present to do more than touch-and that very lightly – upon the salient features of Cambridge life during this, perhaps the most diverting period of the University's existence. It is still fashionable to believe the Church and both the Universities to have passed the whole of these hundred years in a species of post-prandial slumber. Colleges are said to have become mere port-drinking societies; and the daily life of the Cathedral Chapters has been described quite as tersely and as disobligingly by numerous writers. Truly, the manners of the time were not over nice; but the impartial student of morals can well trace throughout the century a steady, if slow, revival from that dire sort of profligacy which marked the social life of the Stuart period. For the first time since the age of the Tudors, English architecture and the other arts not only revived, but attained the dignity of a conscious and coherent style. Gainsborough, Romney, Reynolds took the place once filled by such as Lely. Wren, Hawksmoor, Vanbrugh, Adam gave to many an English building a fame which has not been confined to these islands. An intelligent taste in furniture, plate, porcelain, and fabrics became almost general in decent society. Music was widely cultivated, and literary effusions which did not conform, however dully, to the accepted models of the day found neither publisher nor reader.

Every merit and, it must be admitted, every demerit of the age is observable in the life of the University during these hundred years. Certainly there was a prodigious decay in University ceremonial, and the antiquaries shook their heads not perhaps without reason. Poor Hearne, noting the first Shrove-Tuesday morning on which the ancient "Pancake bell" did not ring in Oxford, ventured upon the aphorism: "When laudable old customs alter, 'tis a sign learning dwindles". Baker, Cole, and Gunning at Cambridge were doomed to see many cherished quaintnesses pass from the daily life of the academy. The ceremonies attending the Creation of Doctors in the several Faculties were gradually shorn of their symbolic splendour. These had involved in each case the use of a Ring and a Book. A candidate for a Doctorate in Law might be seen at such times to engage in a whispered colloquy with the Professor of his Faculty. This, perhaps the most picturesque and most formal part of the ceremony of Creation, was known as "solving a question in the ear of the Professor". Good Master Gunning could not have failed to take pleasure in the circumstances which attended the University Sermon on Tuesday in Holy-week. On this day the sermon was preached, not in Great St. Mary's, but in the Anglo-Saxon Church of St. Benet. Before the sermon the preacher was directed to say: "John Meer, Esquire Bedell, long since of this University, gave a tenement situate in this parish; in consideration whereof the sermon is here this day. He left a small remembrance to the officers of this University provided they were present at the Commemoration; and was also not unmindful of the poor in the Tolbooth and Spittal-house." At the conclusion of the sermon a distribution was made of this "small remembrance". It worked out at three shillings and fourpence for the preacher, sixpence for the Vice-Chancellor, and fourpence each for the other dignitaries. A disbursement of three shillings covered the other part of this amiable bequest! During the whole of this period the University exercised its ancient right of supervising all weights and measures. Officers known as Taxors performed the necessary testing, and at such times were authorized to destroy any faulty measures which came under their observation. There existed, too, for the punishment of disorderly women, a University prison or bridewell called "the Spinning House", and one of the duties of the Proctors consisted in the visitation and inspection of any quarter of the town or its immediate environs in which vice was reputed to lurk. The Spinning House existed, as a building, within the recollection of the writer. It stood on ground now occupied by the Fire Station in Regent Street. These particular jurisdictions and the fact that the Vice-Chancellor took precedence of the Mayor at all public functions constituted the chief ground for that ill feeling between Town and Gown which was a notorious feature of Cambridge life even as late as 1850. The eighteenth century in Cambridge actually opened with a singularly unseemly fracas between the Municipal and University authorities. The Mayor himself and two of the Aldermen were implicated. The circumstances may be gathered from the "humble submission" of the former, dated October 2, 1705, in which he pleads guilty to having "denied unto Sir John Ellys, the Vice-Chancellor, the precedence in the joynt seat at the upper end of the guildhall... which refusal was the occasion of a great deal of contempt and indignity offered by some rude persons to the said Vice-Chancellor and his attendants". The "submission" of Mr. Francis Perry and his colleague followed in due course. These gentlemen owned to having opposed the Vice-Chancellor, "whereby divers unworthy affronts and indignities were occasioned the said Vice-Chancellor". Their submission did not come for the asking. Till they were made, however, the University authorities had "discommuned" half the townsfolk: which meant that an undergraduate who dared to deal with the burgesses might be sent down, whilst a graduate, for the same conduct, might be deprived of his degrees. This jurisdiction is still retained. During this century sport became a prominent and important feature of University life. No longer confined, as were the students of an earlier day, to the precincts of the University, nor fenced about with clerical rules aiming at an almost monkish propriety, graduates and undergraduates began to ride, hunt, and shoot over the countryside. Towards the close of the century the crowd of "persons of quality" who attached themselves to the University as Noblemen or Fellow Commoners necessarily included a number of "raffish" spirits, who cared little for the convenience of others. A satirical advertisement touching this question appeared in the Cambridge Chronicle for 30 August, 1787, in which the neighbouring farmers, after announcing that their corn is in many places still standing, "beg the favour of the Cambridge gunners, coursers, and poachers, whether gentlemen, barbers, or gyps of Colleges", to let them get home their crops; and they continue: "If we might breed on our own premises a bird or a hare for ourselves, and have a day's shooting for our landlords, or our own friends, we should acknowledge it a great indulgence and politeness!" But a good deal of miscellaneous sport could be had within actual hail of the Colleges. "In going over land now occupied by Downing Terrace," says Gunning, "you generally got five or six shot at snipe. Crossing the Leys you entered on Cow Fen. This abounded with snipes. Walking through the osier bed on the Trumpington side of the brook you frequently met with a partridge and now and then a pheasant." But, for the undergraduates and the juniors generally, there were amusements enough. Though expressly forbidden, cockfighting was popular; and there were more gaming, taverning, and the like diversions than sober-minded persons could be expected to approve of. Not only the students, but the seniors fell into cliques or sets each with its favourite coffee-house, where one might peruse the news sheets, make a bet, or pick a quarrel. Clubs, for the most part of an avowedly convivial nature, sprang into being, some of which, like The True Blue, remain to this day.

With the seniors, horse-exercise and bowls were popular pastimes. The Cambridge bowling greens were, and are, justly celebrated; and agreeable riding was to be had in most directions out of Cambridge. Along "The Backs" the mounting stones put up at this time may still be seen. Those Fellows of Colleges who held livings or curacies just outside the town rode to and from their cures in the performance of their duties. Other folk, like Dr. Samuel Peck, rode daily to the town on matters of private business. It is recorded of this worthy member of Trinity College that he gave advice on legal subjects for nothing. "Sam Peck never takes a fee," he would say. But he was wont to add that he saw no objection to a "present" in return for his services. Thus presents-mostly in kind-invariably followed upon any disbursement of his legal knowledge. The figure of Sam Peck, mounted on his horse and loaded with gifts, is preserved for us in a print now somewhat scarce, but of which a copy hangs in the smaller Combination Room at Trinity. This charming picture is also interesting as showing that for a celibate Fellow of a College in those days the present of a pair of lady's stays was not thought wholly unsuitable. Fellows of Colleges, it should be borne in mind, were by statute debarred from matrimony; and, saving the case of some few Civilians, i.e. graduates in Civil Law, they were bound to take Holy Orders. Thus were the Universities filled with numbers of gentlemen who in order to teach pagan literature on a comfortable stipend, had been forced to assume the garb and too often the duties of the Christian priesthood. To give them their due, however, they met the statutable requirements of the place with a fortitude which never sought to escape the gibes of those professed cynics in which the age abounded; and there is surely a healthy candour in the answer which a young Cambridge clergyman returned to Mr. Gunning's congratulations on his appointment to a convenient living. "My predecessor," said he, "was a man of my own age, but was providentially attacked with gout in the stomach, and died before he could receive medical attention." The eighteenth century was pre-eminently an age of oddities. Just as people collected books, china, and rare prints, so in a sense they collected men, and delighted to record whatever was whimsical in their fellow creatures. The reminiscences of Henry Gunning, sometime Esquire Bedell, teem with delightful anecdotes. To students of men and manners, it is one of the best books in the language. Its comparative rarity must excuse the present writer for drawing so largely upon it. Of Gunning's recollections of the seniors of his young days none are better than his stories of Dr. Samuel Ogden. Dr. Ogden took his first degree as early as 1737, his D.D. in 1751 and was appointed Professor of Geology in 1764. Visitors to the Round Church may like to hear of him, for there was he wont to preach. He was extremely fond of the pleasures of the table; and, while it is not expressly stated of him, there seems good cause to believe that like that fine old exciseman immortalized by Hawthorne in his preface to The Scarlet Letter, "there were flavours on his palate which had lingered there not less than sixty years". His was the saying: "A goose is a silly bird – too much for one and too little for two". At a dinner party, on a dish of ruffs and reeves coming up very much underdone, he answered his hostess's enquiry as to their merit by observing, "They are admirable, madam, raw! What must they have been had they been roasted?" When dining at Wimpole with Lord Hardwick, High Steward of the University, the butler, in mistake for champagne – then a great rarity – handed round glasses of pale brandy. Lord Hardwick himself instantly detected the error, but was too late to prevent Dr. Ogden emptying his glass. Lord Hardwick could not suppress an exclamation of surprise. "I did not mention it to you, my lord," said Ogden, "because I felt it my duty to take whatever you thought fit to offer me, if not with pleasure, at least in silence."

It is a true saying that "where there be strange folk there will be stranger doings", and the history of Cambridge in the eighteenth century is charged with accounts of the oddest happenings. Could anything be more extraordinary, for example, than the circumstances which attended the election of Provost George at King's College in January, 1743? Twenty-two of the Fellows were for George, sixteen for Thackeray, and ten for Chapman, who was the Tory candidate. A regular faction fight ensued. The election was bound by statute to take place in the Chapel, and there the Fellows remained in conclave for thirty-one hours. Neither side would give way, and until they had agreed on their man none were permitted to stir out of the Chapel, "nor none permitted to enter", says a historian in 1753. An unsigned letter from Cambridge, quoted by Sir Henry Maxwell Lyte in his history of Eton College, gives a graphic account of these incidents: "The Fellows went into Chapel on Monday before noon in the morning as the statute directs. After prayer and sacraments they began to vote. . . . A friend of mine, a curious man, tells me he took a survey of his brothers at the hour of two in the morning, and that never was a curious or more diverting spectacle. Some, wrapped in blankets, erect in their stalls like mummies; others asleep on cushions like so many gothic tombs; here a red cap over a wig; there a face lost in the cape of a rug. One blowing a chafing-dish with a surpliced sleeve; another warming a little negus or sipping 'Coke upon Littleton' i.e. tent and brandy. Thus did they combat the cold of that frosty night, which has not killed many of them to my infinite surprise." It is worth noting this determination of the Fellows of King's to act statutably, for the air was pretty full of unstatutable proceedings afterwards. It was apparently as a protest against some irregularity of this kind that one of the Scrutators (Mr. Tyrwhitt of Jesus) refused his key to the Vice-Chancellor when that dignitary desired to fix the University seal to a loyal address to the Crown on the subject of the American Rebellion. Dr. Farmer, however, was not a man to be baulked by trifles. He obtained the services of a blacksmith, and the seal was put to its appointed purpose without further delay. Dr. Farmer was Master of Emmanuel, and one of the best known men of his time. With Malone, Reed, and Steevens he formed a coterie which was known in Cambridge as "the Shakespeare gang". Farmer knew the Elizabethans by heart, and he made Emmanuel Parlour, as the Combination Room of the College was then called, a centre of literary tabletalk. His was an amiable personality. Though a strong Tory, he never allowed political bias to impair his friendships. "This is a Whig pipe, Master Gunning," he would say, with a sly twinkle. "It has a twist the wrong way." It was in Emmanuel Parlour that Dr. Johnson made one of his best sallies. The story is told by Isaac Reed, who was present. Someone asked why county squires should be addicted to rural sport above everything else. "Sir," said Dr. Johnson, "I have found out the reason of it, and the reason is that they feel the vacuity which is in them less when they are in motion than when they are at rest." It was during Dr. Farmer's mastership that Emmanuel celebrated the two hundredth anniversary of its foundation. For some days before the actual feast which was to take place in honour of the occasion, the inhabitants of the College were delighted with the spectacle of several "lively turtles" disporting themselves in tubs of water. William Pitt and the Earl of Euston, then the Members of Parliament for the University, were present at the banquet. The convivialities were kept up in the Parlour till a very late hour. Here Dr. Randall, the Professor of Music, "was called upon for his celebrated song in the character of a drunken man. The representation was so faithfully given that Mr. Pitt was completely deceived, and expressed some anxiety lest the worthy professor should meet with an accident when leaving the College." But good Dr. Farmer was never more in his element than when sitting in what was called "the Critics' Row" at the Playhouse specially set up during the weeks in which Stourbridge Fair held the attention of the three counties. Mention has already been made of this celebrated Fair. During the eighteenth century it was by far the largest Fair in the country. Every trade was represented, and here many of the good folk of Cambridgeshire, Huntingdon, and the Isle of Ely made the principal part of their household purchases for the year. People came from London and elsewhere to be present at the opening festivities. The declaration of the Fair was a matter of University as well as civic ceremonial. The Vice-Chancellor and the other University officers, attended by the noblemen and other notables, drove to the Fair, which was duly proclaimed by the Registrary of the University. The Senior Proctor provided cakes and wine at the Senate House before starting. To the University dignitaries and their guests was set apart a certain Tiled Booth, where they dined. The menu at the Vice-Chancellor's table never varied. It consisted of a large dish of herrings, a neck of pork roasted, a plum pudding, a leg of pork boiled, a pease pudding, a goose, and a huge apple pie, while a round of beef graced the centre of the board. Before the end of the century this dinner had degenerated into a sort of oyster luncheon. During this and the Midsummer or "Pot" Fair there was a deal of drunken and riotous behaviour not confined, alas! to the townsfolk or the peasant classes. It is reported that tipsy Masters of Arts, many Fellows of Colleges, and clergymen were to be seen with linked arms jostling the passers-by.

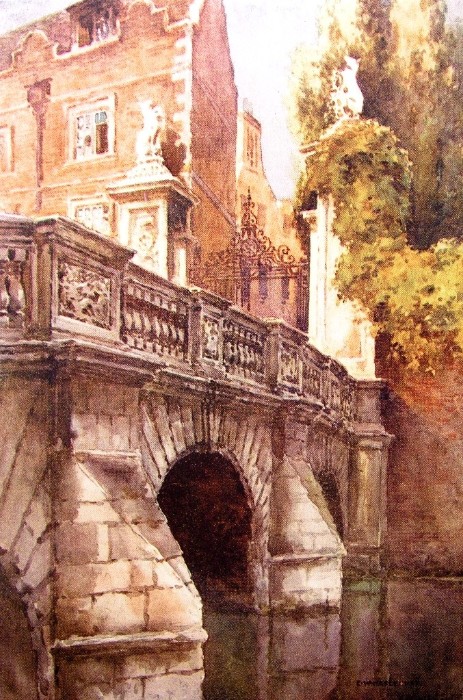

To read but this side of University history one might suppose an academy in which such things were possible would hardly be able to claim to have done much for learning during this period. But Cambridge was no worse as a school for manners than was any other place of education at this time; while the period is one to which we look back to-day as the age of Newton, Bentley, and Porson, – names which alone are sufficient to raise the University into the first place as a seat of learning. The poets, Prior, Gray, Coleridge, and Wordsworth had their education in Cambridge before the century closed. So also did Laurence Sterne. Halifax, the two Walpoles, Lord Camden, Lord Chesterfield, Lord Ellenborough, Lord Bathurst, Lord Thurloe, Pitt the younger, Castlereagh, Wilberforce, Denman were some of the illustrious Cambridge men who found places in the great world of that day; while Paley and Charles Simeon were prominent in the religious life of the time. Many buildings of importance, all designed in good taste, grew up in Cambridge during this century. The library of Samuel Pepys, including the manuscript of his celebrated Diary, was left to his old College of Magdalene in 1703, and reached Cambridge in 1725, when it was placed in what are now called the Fellows' buildings, a range built to do honour to the bequest. To the University Library, enriched by King George I's present of Bishop Moore's collection, was added a new wing designed in the Classical style. The Senate House as we now see it is an eighteenth-century building, and a fine example of its period. At King's College the Fellows' building by Gibbs is another notable addition to the architecture of the place, and the alterations at Clare, Trinity Hall, and Emmanuel are all good of their kind. The beauty of Cambridge does not consist in broad streets or in imposing public buildings. The greater Colleges lie with their gatehouses towards the town, their courts and lawns stretching towards the river, which is spanned by their private bridges. Beyond the river the eye is charmed with a vista of tall trees and flowery gardens. In every College there lurk particular treasures. Corpus Christi, with its old Court abutting on the Saxon Church of St. Benet, where in bygone days the scholars were wont to worship, can show the hall in which Kit Marlowe dined and Parker presided. This College has one of the most interesting libraries in the University, and one of the best collections of plate in the country. Jesus College has an unique chapel. Norman and Early English masonry, fine old stalls, and a mediaeval organ may here be seen, and, for those who care for such things, there are windows by Morris and Burne-Jones. Examples of Wren's work in Cambridge have already been noticed. The bridge built from his designs at St. John's is illustrated in the present volume. No one should miss all there is to see in this stately College. The Combination Room is a typical Tudor gallery; and on Feast Nights, when illuminated with wax candles in silver sconces, it presents a picture unforgetably beautiful. Trinity and St. John's are the only Colleges possessed of statuary. In the antichapel of the former College the statues of Newton, Bacon, Barrow, Macaulay, Whewell, and Tennyson form a striking group. That of Newton is by Roubiliac, and some busts by this admirable master may be seen in the College library, where too is the celebrated statue of Byron by Thorwaldsen, and numerous enrichments of the bookcases by the hand of Grinling Gibbons. This library, which is one of the principal Collegiate libraries in Europe, has over 100,000 volumes. Among its manuscripts are the celebrated Canterbury Psalter, a volume of Milton manuscripts (including the first sketch of Paradise Lost), the manuscript of Tennyson's In Memoriam, that of Thackeray's Esmond, and several Byron manuscripts. The library of St. John's College is second only to that at Trinity. It is approached by a staircase of singular beauty. At Magdalene is the Pepys Library; and the libraries of Peterhouse, Trinity Hall, and Queens' are good specimens of mediaeval college collections. The University has two public libraries. Of these the University Library proper enjoys the right to a copy of every book printed in the realm. It numbers some 500,000 volumes, – and is rich in every kind of literature. The rule which allows M.A.'s and certain B.A.'s to borrow books, and which gives readers access to the shelves, makes this library, as Lord Acton said, "the only useful library in Europe". The library of the Fitzwilliam Museum includes a remarkable collection of musical manuscripts, the most valuable of which are manuscripts of Bach, Handel, and Beethoven. During the last hundred years Cambridge has been enriched with numerous laboratories and several collegiate institutions. Of the latter the most important is Downing College, built in 1805. Two professors have their maintenance here: one of Medicine, the other of the Laws of England. On Downing property the present Law Schools, Geological Museum, and other of the more recent habitations of science have been built. The great Cavendish Laboratory, to which the seventh Duke of Devonshire was a conspicuous benefactor, was built in 1874. Almost every branch of science now possesses its special museum, while art and the study of antiquities are served by the Fitzwilliam and the Archaeological Museums.  Clare College from the Backs Cambridge to-day is a large and complex community: the undergraduate population alone has reached nearly four thousand souls. The Senate, or body of M.A.'s having voting powers in the government of the University, numbers over seven thousand persons; while the total number of members of the University who still keep their names "on the boards" stands at 14,758. Every kind of study, from astral chemistry to engineering, finds among this mass of people some professed teachers and eager students. All this has not been a matter of natural growth. The nineteenth century saw far-reaching changes imposed upon the University; though for some time, most Fellows of Colleges were still required to take Orders, and the rule of celibacy was enforced. By the removal of these restrictions and by the abolition of Religious Tests, the University has reaped much benefit. But it has not been all gain. The amenities of College life in many of the smaller societies have been considerably interfered with, and that "corporate sense" which has hitherto been the strength of the college system has been weakened. On the other hand, the additions which have been made to the recognized fields of intellectual activity have indisputably made for the utility of Cambridge as a centre of education; though it is possible that the demand for young teachers, both public and private, by drawing men away from private study, may tend to lessen the value of the University as a contemplative body. Of this danger not everyone seems unconscious. As the seventeenth century was the age of Bacon, and the eighteenth century that of Newton, so the nineteenth century has been called the age of Darwin. Thus has Cambridge sent three of her sons to revolutionize the study of Natural Philosophy. Among Cambridge scientists of modern times are Adams, Airy, Herschell, Clarke-Maxwell, Stokes, Lords Kelvin, Rayleigh, Avebury, Sir James Dewar, and Sir Joseph Thompson. Cambridge as a school of medicine has been celebrated ever since the time of Caius. Its importance at the present moment is largely owing to the life and labour of the late Sir Michael Foster. Numerous Cambridge men have held professorships at Oxford during the century. The names of Maine, Sir F. Pollock, and Mr. Sidgwick at once occur to the mind; and to-day the chairs of Astronomy, Physics, Botany, Classical Archaeology, and English Literature in that University are occupied, by Cambridge men. From Cambridge, too, come the Astronomer Royal, his immediate predecessor, and most of the provincial and colonial astronomers. Popular fallacies die hard. But it is indeed remarkable that Cambridge should be supposed to give herself over to mathematical studies, when it is remembered that she produced in Bentley and Porson the two greatest classics that England ever knew; while in the nineteenth century Munro, Jebb, and Headlam have won European reputations as classical scholars; and, of the older Universities, Cambridge alone confers a purely classical degree. The Cambridge School of Theology is associated with the names of Westcott, Lightfoot, and Hort. Modern Cambridge has been prolific in men of letters: Byron, Macaulay, Thackeray, Kinglake, Tennyson, Fitzgerald, Grote, Kingsley, Seely, F. D. Maurice, Samuel Butler, Leslie Stephen, and Maitland are names taken at random. The list of her public men is a long one and includes the great Whig peers from Palmerston, Melbourne, Grey, and Lansdowne to such men as the late Duke of Devonshire and the late Earl Spencer: the senior branch of the House of Cecil has been uniformly faithful to Cambridge since the days of the great Lord Burleigh. The Manners family have been as stoutly Cambridge; and the late Duke of Rutland, better known as Lord John Manners, was a familiar figure in the University. It is a Cambridge College that can claim at this moment the Speaker, the Lord Chief Justice, the Leader of the House of Lords, the Leader of the Opposition in the Commons, the Viceroy of India, the Ex-Viceroy, and the retiring Governor-General of Canada. Cambridge as a home of legal studies has been famous since the sixteenth century: Lyndhurst, Cranworth, Pollock, Fitzjames Stephen are legal luminaries of modern times. Trinity Hall is the College with which the study of law is particularly associated. For two hundred years this College practically controlled the Court of Arches, which until the nineteenth century was some way advanced took cognizance of all Probate and Admiralty cases, as well as of causes arising out of ecclesiastical jurisdictions. For some time the Masters and Fellows appointed the Dean of Arches, and the Master enjoyed a right to rooms in Doctors' Commons. Among learned Civilians who have presided over the destinies of "the Hall" are Sir James Exton, Sir Nathaniel Lloyd, Sir Edward Simpson, and Sir William Wynne. The last of this order (for the Court of Arches lost its civil jurisdiction at this time) was Sir Herbert Jenner Fust, whose name will long be remembered in connection with the celebrated Gorham judgment. Sir Herbert was succeeded in the Mastership by the late Sir Henry Summer Maine, of Pembroke College, sometime Corpus Professor of jurisprudence at oxford. The reputation of a College for this or that study is, however, less precious to its more thoughtful inmates than are those associations with famous men long since dead which cling to every grove and every court in Cambridge: to Byron's pool at Grantchester; to Milton's mulberry tree in the Fellows' garden at Christ's; to the little tower at Queens' in which Erasmus studied; to the rooms occupied by Gray at Pembroke; to Newton's at Trinity; or to Wordsworth's at St. John's. Sometimes such traditions are well founded; but if they be not, what matter? The strength and value of such things lie in their power to cause even the youngest of us to see humanity as a grave pageant, of which we may be witnesses though only for a space. But membership of an English University carries with it experiences more personal and more intimate than these. A man may deem himself to be bestowing scant notice upon his surroundings, and yet there are a hundred impressions made upon him by sights and sounds, in these his student days, which pass patternwise into the fabric of his nature. Other phases of College life are remembered in more detail: hours passed in anxious study for the schools; boisterous gatherings when, with old wine in young bellies, almost anything seemed worth the saying; eager struggles in the field or upon the river, when the glory of the College really did seem to depend upon the muscles of some eight or fifteen carefully-dieted young men. One recalls these states of mind as facts; but they have no corresponding values in the world of sense. The really haunting memories are those of particular firesides; of the outlook from this or that window seat; of a moonlit court in summer-time, of the scent of flowers there and of the babble of the fountain; of choir music by taper light in winter; and of the ordered chimes leisurely perpetuating their Tudor cadences. Such thoughts, such recollections

THE END. |