|

CHAPTER

II

AT

THE FAIRY'S

THE Fairy Bérylune’s Palace stood at the top of a

very high mountain, on the

way to the moon. It was so near that, on summer nights, when the sky

was clear,

you could plainly see the moon's mountains and valleys, lakes and seas

from the

terrace of the palace. Here the Fairy studied the stars and read their

secrets,

for it was long since the Earth had had anything to teach her.

"This old planet no longer

interests me!" she used to say to

her friends, the giants of the mountain. "The men upon it still live

with

their eyes shut! Poor things, I pity them! I go down among them now and

then,

but it is out of charity, to try and save the little children from the

fatal

misfortune that awaits them in the darkness."

This explains why she had

come and knocked at the door of Daddy Tyl's

cottage on Christmas Eve.

And now to return to our

travellers. They had hardly reached the

high-road, when the Fairy remembered that they could not walk like that

through

the village, which was still lit up because of the feast. But her store

of

knowledge was so great that all her wishes were fulfilled at once. She

pressed

lightly on Tyltyl's head and willed that they should all be carried by

magic to

her palace. Then and there, a cloud of fireflies surrounded our

companions and

wafted them gently towards the sky. They were at the Fairy's palace

before they

had recovered from their surprise.

"Follow me," she said and led

them through chambers and

passages all in gold and silver.

They stopped in a large room

surrounded with mirrors on every side and

containing an enormous wardrobe with light creeping through its chinks.

The

Fairy Bérylune took a diamond key from her pocket and opened

the wardrobe. One

cry of amazement burst from every throat. Precious stuffs were seen

piled one on

the top of the other: mantles covered with gems, dresses of every sort

and every

country, pearl coronets, emerald necklaces, ruby bracelets...

Never had the Children beheld such riches! As for the Things, their

state was

rather one of utter bewilderment; and this was only natural, when you

think that

they were seeing the world for the first time and that it showed itself

to them

in such a queer way.

The Fairy helped them make

their choice. Fire, Sugar and the Cat

displayed a certain decision of taste. Fire, who only cared for red, at

once

chose a splendid Mephistopheles dress, with gold spangles. He put

nothing on his

head, for his bread was always very hot. Sugar could not stand anything

except

white and pale blue: bright colours jarred on his sweet, nature. The

long blue

and white dress which he selected and the pointed hat, like a candle

extinguisher, which he wore on his head made him look perfectly

ridiculous;

but he was too silly to notice it and kept spinning before the glass

like a top

and admiring himself in blissful ignorance.

The Cat, who was always a

lady and who was used to her dusky garments,

reflected that black always looks well, in any circumstance,

particularly now,

when they were travelling without luggage. She therefore put on a suit

of black

tights, with jet embroidery, hung a long velvet cloak from her

shoulders and

perched a large cavalier hat, with a long feather, on her neat little

head. She

next asked for a pair of soft kid boots, in memory of Puss-in-Boots,

her

distinguished ancestor, and put a pair of gloves on her fore-paws, to

protect

them from the dust of the roads.

Thus attired, she took a

satisfied glance at the mirror. Then, a little

nervously, with an anxious eye and a quivering pink nose, she hastily

invited

Sugar and Fire to take the air with her. So they all three walked out,

while the

others went on dressing. Let us follow them for a moment, for we have

already

grown to like our brave little Tyltyl and we shall want to hear

anything that is

likely to help or delay his undertaking.

After passing through several

splendid galleries, hung like balconies in

the sky, our three cronies stopped in the hall; and the Cat at once

addressed

the meeting in a hushed voice:

"I have brought you here,"

she said, "in order to discuss

the position in which we are placed. Let us make the most of our last

moment of

liberty..."

But she was interrupted by a

furious uproar:

"Bow, wow, wow!"

"There now!" cried the Cat.

"There's that idiot of a Dog!

He has scented us out! We can't get a minute's peace. Let us hide

behind the

balustrade. He had better not hear what I have to say to you."

"It's too late," said Sugar,

who was standing by the door.

And,

sure enough, Tylô

was coming up, jumping, barking, panting and delighted.

The Cat, when she saw him, turned away in disgust.

"He has put on the livery of

one of the footmen of Cinderella's

coach.

It is just the thing

for him: he has the soul of a flunkey!"

Delighted

with the importance of his duty, undid the top of his robe, drew his

scimitar

and cut two slices out of his stomach

Delighted

with the importance of his duty, undid the top of his robe, drew his

scimitar

and cut two slices out of his stomachShe ended these words with a

"Fft! Fft!" and, stroking her

whiskers, took up her stand, with a defiant air, between Sugar and

Fire. The

good Dog did not see her little game. He was wholly wrapped up in the

pleasure

of being gorgeously arrayed; and he danced round and round. It was

really funny

to see his velvet coat whirling like a merry-go-round, with the skirts

opening

every now and then and showing his little stumpy tail, which was all

the more

expressive as it had to express itself very briefly. For I need hardly

tell you

that Tylô, like every well-bred bull-dog, had had his tail

and his ears cropped

as a puppy.

Poor fellow, he had long

envied the tails of his brother dogs, which

allowed them to use a much larger and more varied vocabulary. But

physical

deficiencies and the hardships of fortune strengthen our innermost

qualities.

Tylô's soul, having no outward means of unbosoming itself,

had only gained

through silence; and his look, which was always filled with love, had

become

tremendously eloquent.

To-day his big dark eyes

glistened with delight; he had suddenly changed

into a man! He was all over magnificent clothes; and he was about to

perform a

grand errand across the world in company with the gods!

"There!" he said. "There! Aren't we fine!... Just look at this

lace and embroidery!... It's real gold and no mistake!"

He did not see that the

others were laughing at him, for, to tell the

truth, he did look very comical; but, like all simple creatures, he had

no sense

of humour. He was so proud of his natural garment of yellow hair that

he had put

on no waistcoat, in order that no one might have a doubt as to where he

sprang

from. For the same reason, he had kept his collar, with his address on

it. A big

red velvet coat, heavily braided with gold-lace, reached to his knees;

and the

large pockets on either side would enable him, he thought, always to

carry a few

provisions; for Tylô was very greedy. On his left ear, he

wore a little round

cap with an osprey-feather in it and he kept it on his big square head

by means

of an elastic which cut his fat, loose cheeks in two. His other ear

remained

free. Cropped close to his head in the shape of a little paper

screw-bag, this

ear was the watchful receiver into which all the sounds of life fell,

like

pebbles disturbing its rest.

He had also encased his

hind-legs in a pair of patent-leather

riding-boots, with white tops; but his fore-paws he considered of such

use that

nothing would have induced him to put them into gloves. Tylô

had too natural a

character to change his little ways all in a day; and, in spite of his

new-blown

honours, he allowed himself to do undignified things. He was at the

present

moment lying on the steps of the hall, scratching the ground and

sniffing at the

wall, when suddenly he gave a start and began to whine and whimper! His

lower

lip shook nervously as though he were going to cry.

"What's the matter with the

idiot now?'' asked the Cat, who was

watching him out of the corner of her eye.

But she at once understood. A

very sweet song came from the distance; and

Tylô could not endure music. The song drew nearer, a girl's

fresh voice filled

the shadows of the lofty arches and Water appeared. Tall, slender and

white as a

pearl, she seemed to glide rather than to walk. Her movements were so

soft and

graceful that they were suspected rather than seen. A beautiful silvery

dress

waved and floated around her; and her hair decked with corals flowed

below her

knees.

When Fire caught sight of

her, like the rude and spiteful fellow that he

was, he sneered:

"She's not brought

her umbrella!"

But Water, who was really

quite witty and who knew that she was the

stronger of the two, chaffed him pleasantly and said, with a glance at

his

glowing nose:

"I beg your pardon?.... I

thought you might be speaking of a great

red nose I saw the other day!..."

The others began to laugh and

poke fun at Fire, whose face was always

like a red-hot coal. Fire angrily jumped to the ceiling, keeping his

revenge for

later. Meanwhile, the Cat went up to Water, very cautiously, and paid

her ever

so many compliments on her dress. I need hardly tell you that she did

not mean a

word of it; but she wished to be friendly with everybody, for she

wanted their

votes, to carry out her plan; and she was anxious at not seeing Bread,

because

she did not want to speak before the meeting was complete.

"What can he be doing?" she mewed, time after time. "He was

making an endless fuss about choosing his dress," said the Dog. "At

last, he decided in favour of a Turkish robe, with a scimitar and a

turban."

The words were not out of his

mouth, when a shapeless and ridiculous

bulk, clad in all the colours of the rainbow, came and blocked the

narrow door

of the hall. It was the enormous stomach of Bread, who filled the whole

opening.

He kept on knocking himself, without knowing why; for he was not very

clever

and, besides, he was not yet used to moving about in human beings'

houses. At

last, it occurred to him to stoop; and, by squeezing through sideways,

he

managed to make his way into the hall.

It was certainly not a

triumphal entry, but he was pleased with it all

the same:

"Here I am!" he said. "Here I

am! I have put on

Bluebeard's finest dress... What do you think of this?"

The Dog began to frisk around

him: he thought Bread magnificent! That

yellow velvet costume, covered all over with silver crescents, reminded

Tylô of

the delicious horseshoe rolls which he loved; and the huge, gaudy

turban on

Bread's head was really very like a fairy bun!

"How nice he looks!" he

cried. "How nice he looks!"

Bread was shyly followed by

Milk. Her simple mind had made her prefer her

cream dress to all the finery which the Fairy suggested to her. She was

really a

model of humility.

Bread was beginning to talk

about the dresses of Tyltyl, Light and Mytyl,

when the Cat cut him short in a masterful voice:

"We shall see them in good

time," she said. "Stop

chattering, listen to me, time presses: our future is at stake.."

They all looked at her with a

bewildered air. They understood that it was

a solemn moment, but the human language was still full of mystery to

them. Sugar

wriggled his long fingers as a sign of distress; Bread patted his huge

stomach;

Water lay on the floor and seemed to suffer from the most profound

despair; and

Milk only had eyes for Bread, who had been her friend for ages and ages.

The Cat, becoming impatient,

continued her speech: "The Fairy has

just said it, the end of this journey will, at the same time, mark the

end of

our lives. It is our business, therefore, to spin the journey out as

long as

possible and by every means in our power..."

Bread, who was afraid of

being eaten as soon as he was no longer a man,

hastened to express approval; but the Dog, who was standing a little

way off,

pretending not to hear, began to growl deep down in his soul. He well

knew what

the Cat was driving at; and, when Tylette ended her speech with the

words,

"We must at all costs prolong the journey and prevent Blue Bird from

being

found, even if it means endangering the lives of the Children," the

good

Dog, obeying only the promptings of his heart, leapt at the Cat to bite

her.

Sugar, Bread and Fire flung themselves between them:

"Order! Order!" said Bread

pompously. “I’m in the chair at

this meeting."

"Who made you chairman?"

stormed Fire.

"Who asked you to interfere?"

asked Water, whirling her wet

hair over Fire.

"Excuse me," said Sugar,

shaking all over, in conciliatory

tones. "Excuse me .... This is a serious moment.. Let us talk things

over

in a friendly way."

"I quite agree with Sugar and

the Cat," said Bread, as though

that ended the matter.

"This is ridiculous!" said

the Dog, barking and showing his

teeth. "There is Man and that's all!... We have to obey him and do as

he

tells us!... I recognise no one but him!... Hurrah for Man!... Man for

ever!...

In life or death, all for Man!

Man

is everything ....

But the Cat's shrill voice

rose above all the others. She was full of

grudges against Man and she wanted to make use of the short spell of

humanity

which she now enjoyed to avenge her whole race:

"All of us here present," she

cried, "Animals, Things and

Elements, possess a soul which Man does not yet know. That is why we

retain a

remnant of independence; but, if he finds the Blue Bird, he will know

all, he

will see all and we shall be completely at his mercy.

Remember the time when we

wandered at liberty upon the face of the earth!

..." But, suddenly her face changed, her voice sank to a whisper and

she

hissed, "Look out! I hear the

Fairy and Light coming. I need hardly tell you that Light has taken

sides with

Man and means to stand by him; she is our worst enemy .... Be careful!"

But our friends had had no

practice in trickery and, feeling themselves

in the wrong, took up such ridiculous and uncomfortable attitudes that

the

Fairy, the moment she appeared upon the threshold, exclaimed:

"What are you doing in that

corner?… You look like a pack of

conspirators!"

Quite scared and thinking

that the Fairy had already guessed their wicked

intentions, they fell upon their knees before her. Luckily for them,

the Fairy

hardly gave a thought to what was passing through their little minds.

She had

come to explain the first part of the journey to the Children and to

tell each

of the others what to do. Tyltyl and Mytyl stood hand in hand in front

of her,

looking a little frightened and a little awkward in their fine clothes.

They

stared at each other in childish admiration.

The little girl was wearing a

yellow silk frock embroidered with pink

posies and covered with gold spangles. On her head was a lovely orange

velvet

cap; and a starched muslin tucker covered her little arms. Tyltyl was

dressed in

a red jacket and blue knickerbockers, both of velvet; and of course he

wore the

wonderful little hat on his head.

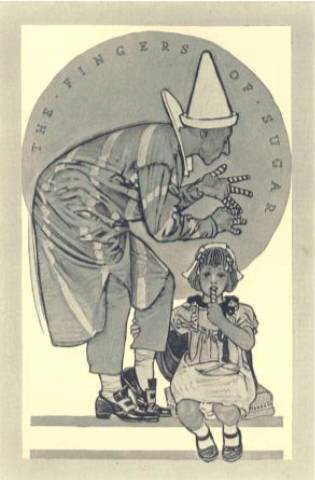

Sugar

also wanted to impress the company and, breaking off two of his

fingers, handed

them to the astonished Children

Sugar

also wanted to impress the company and, breaking off two of his

fingers, handed

them to the astonished ChildrenThe Fairy said to them:

"It is just possible that the

Blue Bird is hiding at your

grandparents' in the Land of Memory; so you will go there first."

"But how shall we see them,

if they are dead?" asked Tyltyl.

Then the good Fairy explained

that they would not be really dead until

their grandchildren ceased to think of them:

"Men do not know this

secret," she added. "But, thanks to

the diamond, you, Tyltyl, will see that the dead whom we remember live

as

happily as though they were not dead."

"Are you coming with us?"

asked the boy, turning to Light, who

stood in the doorway and lit up all the hall.

"No," said the Fairy. "Light

must not look at the past.

Her energies must be devoted to the future!"

The two Children were

starting on their way, when they discovered that

they were very hungry. The Fairy at once ordered Bread to give them

something to

eat; and that big, fat fellow, delighted with the importance of his

duty, undid

the top of his robe, drew his scimitar and cut two slices out of his

stomach.

The Children screamed with laughter. Tylô dropped his gloomy

thoughts for a

moment and begged for a bit of bread; and everybody struck up the

farewell

chorus. Sugar, who was very full of himself, also wanted to impress the

company

and, breaking off two of his fingers, handed them to the astonished

Children.

As they were all moving

towards the door, the Fairy Bérylune stopped

them:

"Not to-day," she said. "The

children must go alone. It

would be indiscreet to accompany them; they are going to spend the

evening with

their late family. Come, be off! Good-bye, dear children, and mind that

you are

back in good time: it is extremely important!"

The two Children took each

other by the hand and, carrying the big cage,

passed out of the hall; and their companions, at a sign from the Fairy,

filed in

front of her to return to the palace. Our friend Tylô was the

only one who did

not answer to his name. The moment he heard the Fairy say that the

Children were

to go alone, he had made up his mind to go and look after them,

whatever

happened; and, while the others were saying good-bye, he hid behind the

door.

But the poor fellow had reckoned without the

all-seeing eyes of the Fairy Bérylune. "Tylô!" she

cried. "Tylô!

Here!"

And the poor Dog, who had so

long been used to obey, dared not resist the

command and came, with his tail between his legs, to take his place

among the

others. He howled with despair when he saw his little master and

mistress

swallowed up in the great gold staircase.

|