| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XII.

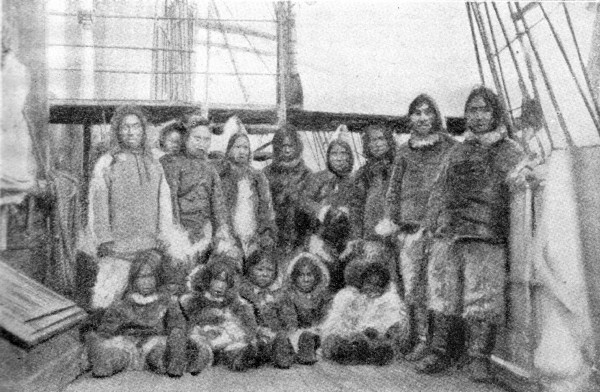

PEARY'S FIRST VOYAGES. The determination to probe the mysteries of the far north which throbbed in Peary's blood found full vent when, in 1 891, he set out on a journey which was to comprehend an overland journey to the north coast of Greenland. Owing to the disasters that had overtaken several government expeditions, Peary was unable to secure support for his scheme from the navy department. This support, however, he secured from the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. He had already gained experience by a short journey in 1886. The trip of 1891 was momentous in several respects; and in one way it was unique: a woman was in the party. This was Mrs. Peary, the same woman who cried out her delight eighteen years later over her husband's attainment of his life ambition. The accounts of the journey which follow are taken from G. Firth Scott's book, "From Franklin to Nansen." Describing the start of the expedition, the writer says: "The party left New York on June 6, 1891, on board the steamer Kite, for Whale Sound, on the northwest coast of Greenland. The voyage was satisfactory in every way until June 24, when an unfortunate accident befell the leader. "The Kite had encountered some ice which was heavy enough to check her progress, and, to get through it, the captain had to ram his ship. This necessitated a constant change from going ahead to going astern, and, as there was a good deal of loose ice floating about, the rudder frequently came into collision with it when the vessel was backing. Lieutenant Peary, who was on deck during one of these maneuvers, went over to the wheelhouse to see how the rudder was bearing the strain. As he stood behind the wheelhouse, the rudder struck a heavy piece of ice and was forcibly jerked over, the tiller, as it swung, catching Lieutenant Peary by the leg and pinning him against the wall of the house. There was no escape from the position, and the pressure of the tiller gradually increased until the bone of the leg snapped. "The doctor, who formed one of the party, immediately set the limb; but the sufferer refused to return home, and when, a few days later, the Kite reached McCormick Bay (near latitude 78 degrees) he was carried ashore strapped to a plank. "The material for a comfortably-sized house was part of the outfit of the expedition, and this was in course of erection the day that Lieutenant Peary was landed. For the accommodation of himself and wife, a tent was put up behind the half-completed house, and, as a high wind arose, the remainder of the party returned on board the Kite. "As the hours passed away the wind became stronger. The tent swayed to and fro, and Mrs. Peary, as she sat beside her invalid and sleeping husband, realized what it was to be lonely and helpless. She and her husband were the only people on shore for miles; her husband was unable to move, and she was without even a revolver with which to defend herself. What, she asked herself, would be the result if a bear came into the tent? She could not make the people on board the Kite hear, and she was without a weapon. Throughout the stay in the North, Mrs. Peary proved herself not only to be a woman of strong nerve and self-reliance, but also an excellent shot with either gun, rifle or revolver. It was, however, as much as she could stand when her anxious ears caught the sound of heavy breathing outside the tent. "For a time she sat still, fearing to disturb her husband, until the continuance of the sound compelled her to look out. A school of white whales were playing close inshore, and it was the noise of their blowing, softened by the wind, which had so disturbed her. But so self-possessed was she over it that her husband did not know till long afterwards the anxiety she had experienced during the first night she spent on the Greenland shore. "The following day rapid progress was made with the house, and some of the party stayed on shore for the night, so that there was always someone within call of the invalid's tent until the house was completed and he was removed into it. By that time the Kite had started home again, and the little party of seven were left to make all their arrangements for the winter. "They had determined to rely entirely upon their own exertions for the supply of meat for the winter and also to obtain their fur clothing on the spot, killing the animals necessary for the material and engaging some of the local Eskimo to make up the suits. Deer would give both meat and fur, and as there was every prospect of the neighborhood affording them in plenty, as soon as the house was up and the stores packed, the majority started away in search of game. "The spot where they were landed, and where they had erected their camp, was on a verdure-covered slope lying between the sea and the high range of bluff hills which towered about 1,000 feet over them. In the spring the ground was covered with grass and flowers; the bay in front was full of seal, walrus, whales and other marine inhabitants, and along the hills behind experience showed that game was present in abundance. The Etah Eskimo, the most northerly people in existence, lived their quaint, out-of-the-world lives along the shore of the bay and neighboring inlets, and, as soon as the camp was settled, they were kept busily employed in the making of fur garments, proving themselves docile and peaceful. It was often difficult for the members of the expedition to realize that the site of their camp, with the abundance of food to be had, was only from fifty to eighty miles from the spots where the castaways of the Polaris suffered so acutely and the members of the Greely expedition slowly starved, many of them to death. For more than a year the little party of seven lived in good health, without a suggestion of scurvy making its appearance and with only one fatality, which, moreover, was accidental." The Pearys gave much time on this expedition to study of the life of the Eskimos, whose traits will be considered later on in this volume. Some of the interesting things they learned were as follows: "Mrs. Peary, as the first white woman the Eskimos had ever seen, was a particular object of attention. As their custom is for men and women to dress very much alike, they could not quite understand Mrs. Peary's costume, and when the first arrivals saw her and Lieutenant Peary together, they looked from one to the other, and ultimately had to ask which of the two was the white woman. "The tribe did not number two hundred in all; they held no communication with the Eskimo farther south, and, except for the occasional visit of a sealer or a whaler, knew nothing of the outer world. None had ever seen a tree growing, nor had they ever penetrated over the ridge of land which lay back from the coast, and over which glimpses were caught of the great ice-cap. The latter, they said, was where the Eskimo went when they died, and if any man attempted to go so far the spirits would get hold of him and keep him there. They consequently warned Lieutenant Peary against venturing. There was no seal up there; no bear; no deer; only ice and snow and spirits, so what reason had a man for going? "Their belongings were extremely simple. A kayak, a sledge, one or two dogs, a tent made of walrus hide or sealskin, some weapons, and a stone lamp, comprised, with the clothes they wore, their property. Wood was the most valuable article they knew, because they could use it for so many purposes, and had so little of it. The possession of knives and needles was greatly desired, but scissors did not appeal to them, since what they could not cut with a knife they could bite with their close even teeth. Money had neither a suggestion nor a use with them; trade, if carried out at all, being merely the bartering of one article for another. "The animals they liked best were dogs and seals; the former being their beast of burden and constant companion, the latter the provider of food, raiment, covering and light. Every seal killed belonged to the man who killed it, but the rules of the tribe required that all larger animals should be shared among the members in the neighborhood; the skin of a bear, however, remaining in the possession of the man who secured it. But so unsophisticated and easy-going are the contented little people that individual property scarcely exists with them; every one is ready and willing to share what he has with another if need be. The articles borrowed, however, are always returned, or made good if broken or lost. No one can either read or write; the boys are taught how to hunt, how to manage the kayak and sledge, and how to make and use the weapons of the chase, while the girls are taught how to sew the fur garments, and keep the stone lamp burning with blubber and moss, so as to prepare the drinking water and the frizzled seal flesh they eat. For the rest, their chief desire is to live as happily as they can, and this, according to those who have been amongst them, they manage to do merrily and well. "During the visits paid to the different encampments by Lieutenant Peary arid his wife, about a score of dogs were obtained, a number which would be sufficient to carry out the work of the ensuing spring. They were usually obtained in exchange for needles and knives, but the purpose for which they were needed always formed a subject of wonder to the unambitious 'huskies.' " The winter in Greenland passed without extraordinary incident. By the middle of April preparations were made for pushing on to a point where further knowledge could be gleaned. It was Lieutenant Peary's plan to journey with one sledge — which was followed by a supporting party — into the unknown interior of Greenland, and over a great ice-cap that makes the center of the country a huge mountain. The start was made April 30. Each sledge had a team of ten dogs and was laden with food and scientific instruments. Mrs. Peary, of course, remained in her temporary home. Says Mr. Scott in describing this trip: "The two parties kept together until the costal range was surmounted, and the beginning of the ice-cap was reached. Here the sledge which was to do the great journey was laden with a full load, and the two explorers started forward, Lieutenant Peary leading the way with a staff to which was attached a silk banner — the Stars and Stripes — worked by Mrs. Peary. "The first of the ice-cap was a stretch of some fifteen miles of ice, formed into enormous dome-shaped masses. They toiled up one side but traveled easily down the other, and so on, up and down, until they had attained an altitude of nearly 9,000 feet above the sea level, when they found that they were on a vast expanse of snow. The white unbroken surface stretched away as far as the eye could reach, unbroken by a ridge or rise, everywhere fiat, white and immense. This was the great ice-cap, the frozen covering of the interior of Greenland, the unknown region where no man had yet set foot. "But it was a mistake to term it an ice-cap. They found it to be rather a desert, a Sahara with dry drifting snow instead of the dry burning sand. And, like Sahara, it had its days of storm, when the snow whirled in clouds just as the sand rises before the scorching blast of the simoom. Very wonderful was the first experience of this Greenland dust-storm. The sky overhead was filled with dull grey clouds, heavy and opaque, and the gloom spread all around, so that whichever way one looked there was the same impenetrable veil of grey gloomy haze. The snow lost its dazzling whiteness and took instead the tint of the gloom of the surrounding atmosphere. Then the wind came, at first in fitful gusts but later growing into a steady blow, the opening squalls lifting the dry surface snow and whirling it up in the air. The steady breeze caught it and carried it along in a constantly moving stream some two feet deep, and it was then that the effect of the storm was most pronounced. The drifting particles of snow made a curious rustling noise as they moved and as they whirled around the travelers' legs the feet were hidden beneath the dense moving veil. As a result, it was as though one were walking on nothing and going nowhere, for the grey gloom all around made one unconscious of either direction or space, and the moving snow prevented one seeing the feet or realizing that there was anything solid under them. "The steady hum of the drifting snow, together with its movement, made the brain dizzy, and the two explorers generally found it necessary to form a camp when such a storm came on, the snow soon piling up against their shelter tent and effectually protecting them from the wind. Then, when the breeze had died away and the snow ceased moving, they were able to dig out their sledge and proceed. "A distinct contrast to these stormy days was given by the period of clear sunshine. Then the sky, innocent of a cloud, was a wonderful blue vault overhead, while the snow-covered plateau stretched away on all sides until it was lost in the distance of the horizon. The wonderfully clear air enabled the explorers to see a great distance ahead. At the end of the second day's march after reaching this great snow desert, they found that the surface was gradually sloping north and south. They were on the dividing ridge and, as they passed over onto the downward slope, their progress was naturally at a more rapid rate. A storm, such as has been described, accompanied by falling snow, overtook them, and for three days they had to stay in their shelter. When at length the weather moderated and they were able to get out again they discovered, before resuming the journey, that the dogs meanwhile had eaten six pounds of cranberry jam and the foot off one of the sleeping-bags — a fairly good example of a dog's appetite during a snow-storm. "On May 31 in magnificently clear weather they looked out upon a scene on which no white man had ever yet gazed. In his description of the journey the leader wrote: 'We looked down into the basin of the Petermann Glacier, the greatest amphitheatre of snow and rugged ice that human eye has ever seen.' Away beyond it, a range of black mountains towered in dome-shaped hills, and they made their camp with the expectation of being able to see more of the distant range at the end of another march. But by the time they were able to resume their march a thick fog had come into the air, and for three days they could only see the snow at their feet. They directed their course entirely by compass, but as they were unable to see long distances ahead, they were unprepared for a change in the surface. Before they could avoid it, they found themselves amongst rough ice and open crevices. They were getting onto the Sherard Osborne Glacier, and, in the misty weather they were experiencing, it was difficult to get back onto the smooth ice again. Over a fortnight was spent in getting beyond this rough ground, and at length, on the weather clearing, they found that straight ahead of them a range of hills showed along the horizon above the ice-cap. The appearance of the hills directly in their path decided them to turn their course from due east to southeast, and they were soon able to make out the line of a deep channel running from the northeast to the southwest.  PEARY'S CREW: TILE NEIVROUNDLANDERS WHO MANNED THE ROOSEVELT. Peary has congratulated Newfoundland on its share in the discovery of the Pole, as Captain Bartlett and the erew of the Roosevelt — nineteen in all — hail from Newfoundland.  PEARY'S ESKIMOS: NATIVES WHO ACCOMPANIED PEARY'S EXPEDITION. These are the hardy natives of Etah, to whose assistance the explorer attributes much of his success.

"On July 1, after fifty-seven days of travel, they came to the limits of the ice-cap and stood, silent and amazed, looking down from the summit of the snow desert across a wide open plain covered with vegetation, with here and there a snowdrift showing white, and with herds of musk oxen contentedly grazing over it. Such a discovery was absolutely so unexpected that at first they could scarcely believe their eyes. There was no sign of any human habitation on the land, and, for all that could be learned to the contrary, they were the first human beings who had ever trod upon that plain, on which the yellow Arctic poppies were waving in bloom and over which the drone of the humble bee sounded, though for hundreds of miles around it the accumulated snow of centuries lay frozen into the great mysterious snow-cap and its glaciers. "Having proved that they really were not dreaming, they shot a musk ox, which they used for their own and their dogs' refreshment. Then they stacked their stores and set out with reduced loads across the plain. They walked for four days, exploring, surveying, and examining; and on the fourth of July, the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence by the United States, they stood on a summit of a magnificent range of cliffs, 3,500 feet high, and overlooking a large bay, which in honour of the date, they named Independence Bay. "The latitude was nearly 82 degrees N., and Lieutenant Peary, writing of the discovery, says: It was almost impossible for us to believe that we were standing on the northern shore of Greenland as we gazed from the summit of this precipitous cliff with the most brilliant sunshine all about us, with yellow poppies growing between the rocks around our feet and a herd of musk oxen in the valley behind us. In that valley we had also found the dandelion in bloom and had heard the heavy drone and seen the bullet-like flight of the humble bee.' " For a week the party of investigators remained in this isolated region, 6,000 miles from their friends, and then journeyed back. Over the glistening ice surface they made fast time, and often reached an average of thirty miles a day. Sometimes, when the wind was good, sails were put up on the sledges, and they flew along, like boys with their sleds on a pond. On August 8 the party arrived back at the place where Mrs. Peary had been left, and a short time later the Kite sailed for America, reaching New York September 20, 1892. From a scientific standpoint the results of this expedition were: The discovery and naming of Independence Bay, at 61 degrees north latitude. Determination of the insularity of Greenland, for which Peary received medals from a number of geographical societies. Discovery of Melville Land and Heilprin Land. |

||||||||