CHAPTER XXXII.

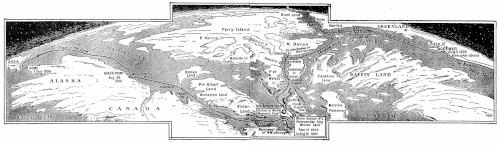

AMUNDSEN'S

DISCOVERY OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE.

A

modest Norseman, Roald Amundsen by name, performed in 1905 one of the

few remaining great feats of Arctic exploration by sailing a ship for

the first time in history through the northwest passage and charting

new land in the region where the gallant Franklin and his companions

lost their lives. Others had crossed on sledges the archipelago that

lies to the north of the American continent, and so bridged the gulf

between the two oceans; but Amundsen was the first to sail a boat

from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Amundsen

was one of those Norwegians who, as soon as their boyhood mentality

begins to dawn, feel their blood stirred by the call of the sea. He

was a student of the Franklin tragedy, and his latter-day hero was

Fridtjof Nansen. He tells of his enthusiasm when he saw Nansen

returning triumphant from his march across Greenland. And it was

Nansen who was largely instrumental in enabling Amundsen to venture

on the trip that was to succeed where Franklin, Parry, Sir John Ross

and others had failed. Amundsen also received the material and moral

aid of the king of Norway. By this powerful backing he was able to

get a ship, and he gathered around him six sturdy Norwegians, like

himself. The small but compact and sympathetic band of explorers

started June 16, 1903, from Christiania in the motor-yacht Gjoa, a

tiny vessel of 47 tons. It seemed almost a toy ship, when it came to

ocean travel and Arctic storms, but its very smallness no doubt had

much to do with its success in riding over shoals and escaping ice

complications.

A

quick trip was made from Norway around the lower coast of Greenland

and through Davis Strait to Godhavn. This point was reached July 5,

1903, and stores of all kinds were taken in. Then the Gjoa pushed

northward in Baffin Bay, making for Cape York, which was the

northernmost point to be reached in that part of the expedition. Cape

York was sighted August 14, but not till after dangerous ice had been

encountered in Melville Bay, often a perilous spot for explorers.

Telling

of this ice, Amundsen says:

"To

the east the whole interior of Melville Bay lay before us. Right

inside, in the farthest background, we could see several mountain

tops. An impenetrable mass of ice filled the bay; mighty icebergs

rose here and there from out of the mass of ice. When we at last

looked back, we saw the fog out of which we suddenly slipped, lying

thick like a wall behind us. Such a sight is one of those wonders

only to be seen in the never-to-be-forgotten seas of ice."

Melville

Bay was not to be a sticking-point for this lucky party, however, and

Cape York was made with ease. There Amundsen met members of the

so-called Danish Literary Expedition to Greenland, led by Mylius

Ericksen, and including Knad Rasmussen, one of the strongest

supporters of Dr. Frederick A. Cook. Felicitations and advice were

exchanged, and the Amundsen party proceeded through Lancaster Sound

to Beechey Island, which was the point where Sir John Franklin had

his last comfortable winter quarters. Amundsen, always an admirer of

Franklin, gives vent, in his account of the trip, to his feelings on

their putting in at the spot where the sturdy Britisher quartered

himself while still in health and hope. It was there that the scurvy,

which was to scourge the crews of the Erebus and Terror most

fearfully, first made its appearance.

After

a short stay the Gjoa was turned south in Franklin Strait and plunged

into a region of mysteries and possible perils. As the point of the

magnetic pole was approached, the compass began to show signs of

being in a strange country. It vacillated furiously, and before the

eyes of the anxious mariners veered gradually until it pointed

southwest. The magnetic pole was at hand.

What

lay before the party, with the ice accumulations always a danger, and

with a "nervous" compass, they could not foretell. But they

sailed the Gjoa on along Somerset Island. Between that island and

Prince of Wales Land Amundsen encountered what he feared was the

long-dreaded ice-barrier. They saw what they took, he says, in the

mirror-like glitter of the calm sea, to be a compact mass of ice

extending from shore to shore. "It seemed evident to me that we

had now reached the point whence our predecessors had been compelled

to return — the border of solid unbroken ice. Happily we were

mistaken, as, in fact, we were several times afterward under similar

circumstances. With the sunlight on the glassy surface of the sea,

with pieces of ice scattered over, these may easily present the

appearance of one solid, continuous mass. This optical illusion is

also enhanced by the *ice blink' constantly occurring in the Arctic

sea. This ice blink magnifies and exaggerates a small block of ice to

such an extent that it looks like an iceberg; especially when looking

at it through a telescope at short range you may easily imagine you

are facing a huge ice-pack. But on the Arctic sea you can never rely

on what you fancy you 'see,' however distinct it may appear."

And

now the compass failed them altogether. Off Prescott Island in

Franklin Strait, Amundsen says, "the needle of the compass,

which had been gradually losing its capacity for self-adjustment, now

absolutely declined to act. We were thus reduced to steering by the

stars, like our forefathers the vikings. This mode of navigation is

of doubtful security even in ordinary waters, but it is worse here,

where the sky, for two-thirds of the time, is veiled in impenetrable

fog. However, we were lucky enough to start in clear weather."

Next

day all Amundsen's fears for the time being were dissipating in a

manner he describes graphically as follows:

"I

was walking up and down the deck in the afternoon, enjoying the

sunshine whenever it broke through the fog. * * * As I walked I felt

something like an irregular lurching motion, and I stopped in

surprise. The sea all around was smooth and calm. * * * I continued

my promenade, but had not gone many steps before the sensation came

again, and this time so distinctly that I could not be mistaken;

there was a slight irregular motion in the ship. I would not have

sold this slight motion for any amount of money. It was a swell under

the boat, a swell — a message from the open sea. The water to the

south was open; the wall of ice was not there."

Winter

was now approaching, and the Gjoa was hard put to it. Once the little

ship was nearly burned when a quantity of petroleum, used as fuel for

the motor, took fire; but the courage and coolness of Amundsen and

his men averted a disaster. Another time the Gjoa ran aground, and

was floated only by throwing overboard all the stores that were piled

on deck. But King William's Land was reached in safety, and on the

southeastern part of the island the Gjoa made port in what one of the

party described as "the finest little harbor in the world."

This was ninety miles south of the magnetic pole as located by Ross.

The

whole party now entered upon a long period of investigation — the

work for which they really had come, rather than to navigate unknown

seas. Their duty was to observe the region of the magnetic pole, to

observe its variation and make a study of the magnetism of the earth.

The

magnetic pole is very little understood. Many suppose the north pole

to be the point toward which the compass points. Not so.

As

Amundsen describes it, "if we fit up a magnetic needle so that

it can revolve on a horizontal axis passing through its center of

gravity (exactly like a grind-stone) the needle will, of its own

accord, assume a slanting position, if its plane of rotation

coincides with the direction indicated by the compass. * * * At the

magnetic north pole, the dipping needle will assume a vertical

position, with its north point directed downwards; at the magnetic

south pole it will stand vertically with its south point downwards."

The

Gjoa as anchored in the "fine little harbor," which they

named Gjoahavn September 12, 1903, and remained there until August

13, 1905. A house was built, in which two of the party pursued

scientific observations, acquaintance was made with the Eskimos of

the region, and much exploratory work was done. A trip was made to

Boothia, where the magnetic pole is situated, and two of Amundsen's

men made a sledge journey along the eastern coast to Victoria Land,

charting much new land, and traveling 800 miles. But these pursuits

came to an end, and when the season for propitious travel was fairly

on, the Gjoa was headed westward for the climax of the journey. She

was maneuvered successfully through the narrowest portion of the

passage, south of King William's Land, and pushed on into channels

whose navigability was yet to be tested. On through Deas Strait and

Coronation Gulf the little motor-vessel held her course, and scarcely

a mishap marred the successful journey.

Describing

the most "ticklish" part of the trip, Amundsen says:

"The

channel now ceased and branched off in the shape of a narrow sound

between some small rocks. The current had probably formed this

channel. The passage was not very inviting, but it was our only one,

and forward we must go.

"As

we turned westward, the soundings became more alarming, the figures

jumped from seventeen to five fathoms, and vice versa. From an even,

sandy bottom we came to a ragged, stony one. We were in the midst of

a most disconcerting chaos; sharp stones faced us on every side,

low-lying rocks of all shapes, and we bungled through zigzag, as if

drunk. The lead flew up and down, down and up, and the man at the

helm had to pay very close attention and keep his eye on the lookout

man, who jumped about in the crow's nest like a maniac, throwing his

arms about for starboard and port respectively, keeping on the move

all the time to watch the track. Now I see a big shallow extending

from one islet right over to the other. We must get up to it and see.

The anchors were clear to drop, should the water be too shallow, and

we proceeded at a very slow rate. I was at the helm, and kept

shuffling my feet out of sheer nervousness. We barely managed to

scrape over. In the afternoon things got worse than ever; there was

such a lot of stones that it was just like sailing through an

uncleared field. Though chary of doing so, I was now compelled to

lower a boat and take soundings ahead of us. This required all hands

on deck, and it was anything but pleasant to have to do without the

five hours' sleep obtainable under normal conditions. But it could

not be helped. We crawled along in this manner, and by 6 p. m., we

had reached Victoria Strait, leaving the crowd of islands behind us."

On

August 17 they anchored off Cape Colborne, after having sailed the

Gjoa "through the hitherto unsolved link in the northwest

passage."

On

August 26 at 8 a. m., Capt. Amundsen was asleep below, when he heard

a rushing to and fro on deck. A few minutes later came the cry "A

sail!" It was a whaling vessel, and it meant that the Gjoa had

reached navigable waters in the western side of the passage.

Says

Amundsen: "The northwest passage had been accomplished — my

dream from childhood. I had a peculiar sensation in my throat; I was

somewhat overworked and tired, and I suppose it was weakness on my

part, but I could feel tears coming to my eyes. 'Vessel in sight!'

The words were magical. My home and those dear to me there at once

appeared to me as if stretching out their hands. 'Vessel in sight!' "

The

Gjoa reached King Point August 29, 1905, after a journey of only

sixteen days from King William's Land, and there made a second winter

quarters. That winter was saddened by the death of one of the members

of the party, the scientist Wiik. The rest pushed on to the end, and

arrived in Nome, Alaska, September 3, 1906.

Amundsen

was established at once as one of the great explorers of the world,

and none received with greater enthusiasm the news of the north pole

discovery than did he.

|