|

APPENDICES

... dans leur sympathie, ils m'ont dû garder place,

Car ils ne savent pas donner à moitié,

On conserve longtemps un beau fruit dans la glace,

Les gens de climat froid sont de chaude amitié.

Et puisque vous avez cette aimable pensée

De vouloir que mes vets vous présentent là-bas,

Dites bien tout d'abord a la foule empressée

Que mon cœur se souvient des nobles Pays-Bas,

Du pays généreux qui ne sait pas proscrire,

Qui s'ouvre a tout martyr, àtout persécuté

Oh chaque citoyen dès l'enfance respire

Avec le vent marin, l'air de la liberté.

Enfin de ce pays que Fart et la pensée

Plus que tous ses trésors, rendent illustre et grand,

Et que vous voit passer dans sa gloire passée

Esprit de Spinoza, palette de Rembrandt!

Francois Coppee

|

I

HYACINTH CULTURE AT HAARLEM IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

CHAPTER I -- INTRODUCTION

SAINT-SIMON, writing in the year 1768, declares there were at

that time in Haarlem nearly two thousand named varieties of the

hyacinth, and we may suppose they had already been about forty years in

cultivation on a soil which seemed particularly adapted for the

purpose, -- a fine upper stratum of grey sand, superposed by the action

of the sea on a thin subsoil of peat, so that Nature prepared, it

seems, many thousand years in advance to produce the delicately-tinted

and exquisitely-scented flower, which rises as if by magic out of the

cold earth in a few weeks' space.

One well-named variety, "Sceptre of David," reminds one of

the long moral preparation of one people chosen out of the nations of

the earth (a stiff soil to work), before the long-desired of the hills

should come, when there should come a rod out of the root of Jesse, and

a flower should rise up out of his root.

If there are "correspondences" in the material and spiritual

worlds, the flower that cometh up in a day has its root in the ages.

The hyacinth is one of the most perfect results of man's Art

-- Art, for Saint-Simon is persuaded that the hyacinth has become what

it is principally through cultivation, and without human patience and

perseverance -- if nature had been left entirely alone -- a much less

pleasing and exquisite flower would have appeared.

Every year new varieties are developed, and hope springs

eternal in the breast of the cultivator. Haarlem, the Paradise of

Flowers, may be especially described as the home of the hyacinth.

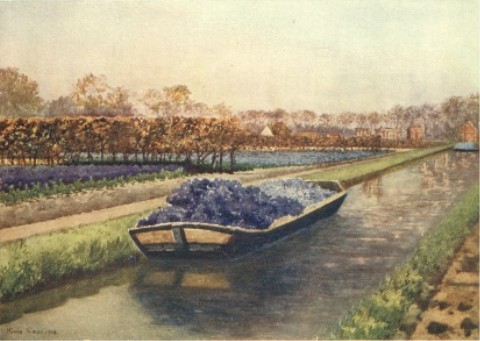

Upon his arrival at Haarlem, the stranger is so dazzled with

the spectacle of the wonderful and brilliantly coloured carpet spread

before his eyes, that he does not at first realise there is yet further

joy to be found in the singular beauty of certain species and varieties

taken individually.

There he sees acres of hyacinths, double and single, in

uninterrupted ranges of pure colour; the only intervals between the

rows being the little grey sand paths, to enable the cultivator to

reach the flowers.

It is difficult for the imagination to picture a piece of

earth so brilliantly enamelled with flowers, and yet such variety and

beauty in detail. The rarest and finest specimens are put apart from

the rest in chosen spots, and these again are arranged in symmetrical

order, with such taste and so unsullied and trim, that one can hardly

believe Nature has been allowed any hand at all in the arrangement. The

florist's art seems to have triumphed almost too completely. Well, one

may say the florists of Haarlem have played the predominant part, and

their long experience, aided by the succours of reason, have shown them

how to assist Nature by seconding her efforts, and thus to raise her to

a stage beyond herself. In any case, the flowers they cultivate seldom

reach such a high state of development elsewhere. However active and

industrious they may be, no amateur, with all his talents, has ever

reached to such surprising perfection -- in strength and form of stem

and blossoms; or to such brilliancy of colouring, though many

possessing both talent and experience have spared neither trouble nor

expense in their endeavours to produce the same result. They are

inclined to attribute their want of success to the nature of their

climate and the soil, and like to regard Haarlem as a place especially

privileged in these respects.

If amateurs had any idea of the spirit of emulation rife

among the Haarlem growers, and the way their whole attention is

absorbed, -- how unceasingly they labour and continually verify their

experiments, always reflecting and improving upon them and making fresh

combinations, -- they would then know the work is not impossible, and

they need only be endowed with the indomitable qualities of the

Dutchman, and they might produce the same results.

There is no doubt that there exists, even in Haarlem, a

sensible difference between growers of the first class and the more

second-rate cultivators; for, although all are imbued more or less with

the same spirit, and enjoy the same advantages of soil, climate, etc.,

yet some, through learning and experience, rise superior to the rest in

this line.

If in other countries amateur growers kept more in touch with

one another, and co-operated as do the Haarlem cultivators, there would

be less occasion for despair. For a good deal of their success conies

from their united efforts and experiments, so that among them all they

have many ways of knowing how to preserve bulbs, to propagate them, and

guard them from destructive accidents.

Nobody knows exactly where hyacinths come from originally --

the name of the hyacinth called "Orientalis," whose origin can be

traced back till it is lost in the obscurity of ages -- seems to imply

that this flower originated in the East, and there has been much

discussion about the fact that Moses in the book of Exodus speaks of

the colour of the hyacinth -- but whether he refers to it only as a

colour, or as a flower, or as a precious stone, it is impossible to say

-- for it has been differently translated in various languages.

Saint-Simon tells us that Dioscorides, in the time of Vespasian,

describes a flower he calls "Hyacinthos" in these words: "L'Hyacinthe a

les feuilles des plantes bulbeuses et la tige dodrantale

(c'est-à-dire de trois paulmes, pans ou empans de haut, on

n'est pas d'accord sur cette mesure non plus), faible, et plus mince

que le petit doigt, de couleur verte, dont le haut s'incline sous le

poids d'une tête chargée de fleurs

purpurescentes." People have argued indefinitely on the precise shade

of "purple," and to this day they have not decided if it should be more

red than blue or more blue than red. The general opinion seems to be

that the original hyacinth was the colour of the natural wild hyacinth

(which is a Scilla?) which grows in the woods, where the red variety is

not nearly as commonly found as the blue.

On the other hand, the first species may have been red, for

in old fables it seems the hyacinth was thought to be red. Ovid relates

how a flower sprang from the blood of the young Hyacinthus,1 whom

Apollo slew by accident with a quota. Others, like Pliny and Pausanias,

say the blood of Ajax, slain near Salamis, was changed into this

flower.

Whatever its original colour, and whatever country it came

from, it is certain that many species have been produced by the

florists of Haarlem, and have entirely originated in their gardens. Yet

it is to be remembered that all came from the old original stock,

however different they have now become. Their natural simplicity has

been lost to a certain extent.

Florists divide hyacinths into four classes:

1. The Single Hyacinth -- the corolla

divided into six segments.

2. Semi-Double -- only slightly

double, with a few petals irregularly disposed behind the single.

3. Double -- the outer petals lined

with an equal number of other petals in regular order.

4. Full Hyacinth -- which has a heart

as full of petals as it can hold.

These four classes furnish a great number of varieties. We

cannot define further without going into their distinguishing features

and numerous subdivisions.

The Full Hyacinth possesses the greater number and best

varieties. It is important a hyacinth should belong to the best (one of

full) varieties -- but this is not sufficient to constitute a good

flower. The petals should grow in very regular order -- especially

those within the heart of the flower, and the petals should as well be

curved back very evenly at their tip. They should also be of a

beautiful clear and decided colour, and this is a great charm in a

hyacinth. As well as being as perfect and decided as possible, the

colour of the inner should harmonise agreeably with the colour of the

outer petals.

In this respect there is nothing to be found

to surpass the Gloria Florurn Suprema2 --

the blossoms being perfectly disposed the full length of the stem,

which rises tall and very straight, but is, unfortunately a little too

thin to support the weight of the flowers. The petals are very pure

white, and their tips fold back with the greatest regularity, forming a

perfectly symmetrical bud (or button). Colours such as blue and black,

red and white are satisfactory combinations. White hyacinths, as a

rule, are the most delicately shaded, but each variety has a beauty

entirely its own.

Of every colour there are kinds which obtain high prices, but

the beauty or merit of a flower is not exactly determined by the

monetary value -- for people pay for novelty; the rarity it is which

enhances the value. However, they must, besides, have other essential

qualities. Gloria Mundi and Franqois Ist, and other blues, which used

to be the only ones which could at all compete with Gloria Florurn

Suprema, have at last found their rival among the white varieties. "Og

Roi de Basan," "Le Comte de Provence," etc., lose nothing by

comparison. Some of the reds, Rex Rubrorum and Mine d'Or have as many

points in their favour. There are now hyacinths of almost every shade.

But only at Haarlem are thousands of varieties and shades to be seen

together, and there one can feast one's eyes to one's heart's content.

When a new kind is raised from seed it causes a great sensation.

Saint-Simon, after expatiating at length on the endurance of

the hyacinth through centuries of growth, ever reproducing itself with

renewed vigour, -- showing no sign of exhausting the stock, says:

"Cependant cet oignon si merveilleux, ~ternel, pour ainsi dire, dans

l'imagination et pr6sent aux yeux pendant tant de sibcles, ne dure

effectivement que quatre ~ cinq ans."

The hyacinth is propagated by its offshoots or young bulbs.

It also reproduces itself from seed. From the seed new varieties are

produced. Hyacinth bulbs will bloom in any direction they are placed,

even upside down -- the flower will grow downwards in a vase of water.

If you take the bulb at the moment of planting, that is, when

it is beginning to show the tender green point of its shoot, the first

thing to do is to examine if it is healthy. It should be round and

full, and not shrivelled; though each variety differs slightly in form,

yet all should be properly rounded in appearance, because this shows

the bulb is in good condition, nor should it be too light in weight for

its size. If it is, it shows it is drying up inside and is deficient in

sap. But to be small in size does not matter, for some of the beautiful

red varieties have very small bulbs, and very often single hyacinths

have larger bulbs than the double.

There is a kind of double hyacinth, white with a red heart,

which is known by its outer tunic, which is always wrinkled and

defective. In spite of its appearance, by its weight and form one may

judge if it is in good condition. The roots often grow like a crown

round the base of the bulb, and the space in the centre is called the

"eye" of the roots. This space is covered with a membrane; and in

choosing bulbs, this is the part you must first examine carefully to

see if there are any signs of decay. There should be no marks of damp

or of mildew in the eye at the base of the bulb.

When the time draws near for planting, the bulb should show

little swollen white points at the base where the roots are to come.

The tunics or suberous leaves (what is called skin on an

ordinary onion) are always covered over with a thin, dry, reddish skin,

which falls off after a time, but is at first useful in protecting the

other tunics when the bulb is in the earth, for it is planted in the

dampest season of the year. No tunic entirely embraces the

circumference of the bulb, but only about two-thirds of it. The tunics

are really an extension (in the bulb) of the long green leaves, only

the part of these leaves which show green above ground fall off in the

end of the year, and the base of them, which remain within the bulb as

tunics, spread and increase till, when they are pushed by each year's

growth from the centre to the outside of the bulb (by the growth of new

stem and leaves within), they get weaker and thinner, until at last

they turn into the dry, red, outside skin, which finally decays and

falls off.

The tunics are of the same substance as the rest of the bulb

(which is composed of fleshy scales), and the difference is so gradual

that it is impossible to see where the fleshy substance of the bulb

begins to change into the suberous quality of the leaves, and yet there

is a very marked difference between the bulb and its leafy scales; they

are, however, an undetachable whole, and you cannot pull off the inner

tunic leaves of the hyacinth from the base, as you can pull off the

leaves of an artichoke.

As soon as the bulb is taken from the ground it begins to

grow and increases rapidly during the three months it lies on the

shelf, and all this time it lives on the sap-nourishment accumulated by

it when in the earth. The sap concentrated in the bulb can preserve it

for a great length of time, but it is not quite sufficient to enable

the bulb to finish all the work it has to do, and if it flowers it will

not have strength enough to bring its seeds to maturity. (Saint-Simon

here observes that this is not attributable to the bulb having no

roots, but to its inward indisposition.)

Some people imagine that a bulb which has been kept from

flowering can reserve itself for the following year. Many such

experiments have been made, and bulbs have been kept back on the

shelves and have not been allowed to flower; they have invariably

perished, and, growers sa)', scarcely a year passes that they have not

tried the experiment, -- they have lost every bulb which was not put

into the ground. As a rule the sap in a bulb will be sufficient

nourishment during its ordinary growth till January or February, but

after that it will begin to grow mouldy and go bad. The moment it is

put in earth or over water, in the proper season, the bulb, which is

just beginning to be exhausted, pumps up sap so vigorously that it

begins at once to throw out roots from almost the first day, and

growers dare not move them again, even a few hours after they have been

put in, to send them away, however carefully packed, even a short

distance, for fear the fresh moisture they have sucked up so quickly

should cause them to rot, and they even consider it a dangerous process

to change them from one place to another, in the same bed, if they have

been but half an hour in the ground. The roots, which are in such a

hurry to show themselves when first the bulbs are planted, perish as

quickly as they grow. They stop growing before the flower is in full

bloom, and are always quite dried up before the seed begins to ripen.

While the root is perishing the flower continues, the stem grows, and

all the flowers expand completely. When the flower is quite over and

the seed is left to ripen, the sap goes into the leaves, which lengthen

considerably, then these die in their turn, till they separate from the

bulb of themselves.

CHAPTER II. -- BULBS

It has already been shown what sort of

appearance the outer tunics

present, and it has been explained how the tunics in general are

formed. We are now going to push our examination further. After

divesting the bulb of seven or eight tunics (or fans), one comes (A)

upon a little thin flattened thread of crimson colour, like a line. It

is, as it were, embedded in one of the tunics; it starts from the base

of the bulb and rises to the extreme top.

Continuing to take away again the same number of tunics, one

comes upon a second thread (B) like the first, A, only that it is less

red and thicker; then, for the third time, taking off another seven or

eight tunics, one meets with a third line or fillet (C), very like the

two first, with this difference, it is quite white and much thicker.

Under the last fillet are the new leaves (or fans), beginning to bud,

about seven or eight in number, and in the centre of them is the stem,

which is going to flower in a few months.

Now all the tunics are supposed to be taken off, and only the

three fillets or threads which we spoke of are left (A, B, C). Fillet A

is all that is left (within the bulb) of the stem which flowered

eighteen months ago.

Fillet C is the remains of the stem of the last flower borne

by the bulb, six months before.

Fillet D is the stem which is about to flower in six months'

time (the flower buds are already sufficiently formed to be seen), and

E contains the stein and tunic leaves, which are to come into bud in

another eighteen months.

If, when the bulb is in full flower, you divest it of all its

tunics, till you come to the flower stem, -- you will find at the base

of it a very tiny bud; if you take away the stem, which easily breaks

off, you will find the bud remains firmly attached to the base of the

bulb. If you open the bud with a penknife, you will see it is composed

of six or seven little leaves (or fans), and inside a tiny stem,

furnished with buds, which has begun to grow already, and from the

moment the bulb is laid on the shelves it increases till the time comes

for putting it again in the earth. We have been speaking all this time

of the double hyacinth. The single hyacinth is somewhat differently

constructed, for it usually throws out several shoots from the sides as

well as from the centre. The single bulb does not appear to last so

long, for its fillets are fewer, but the number of flowering stems it

produces, and the irregularity of their growth, makes it difficult to

follow it in its various stages of development as exactly as one can

the double. By dint of observing, year after year, bulbs, both those in

a good state of preservation and some partially decomposed, it has been

discovered that the bulb always loses the same number of outer tunics

as it gains interiorly new ones. When once a bulb has acquired the

regulation number of tunics, it will always keep to the same number

year by year, and nevertheless every year it is putting forth seven or

eight from its centre. The outer tunics, which we call "red skin,"

regularly shrivel and decay in the earth, and thus they disappear.

The central (fans) or young tunics, when they turn into

leaves, do the work of an air-pump; they are the lungs by which the

plant lives; they dilate in heat and contract in cold. When dilated

they take in the air, with all with which it is impregnated, and they

give it out again with the regularity that an animal breathes through

its lungs.

Plants do not like the shade of trees; they need open air and

sunshine, and they like places where they catch the dew and rain and

mist; the moisture thus obtained through their leaves is better for

them than water poured upon them from a watering-pot.

Planted in hot-houses or under glass they do without much

water, because the hot air produces vapour by the sun's rays from above

or from the fire beneath, and it is necessary to introduce a little air

in order to let it evaporate (but the plants must not be chilled by

cold seizing them in the process). Hyacinths which are protected by

planks sometimes do better than those under glass.

The planks are lifted and the plants find themselves exposed

to the open air, this is only done when the air is not likely to injure

them. To be kept constantly under glass or in a room sometimes affects

their colour and shape. It also spoils their colour to be exposed to

heavy rain or a very hot sun, which exhausts them. The leaves (as the

leaves of a tree) turn on their pedicels one side to the earth, for one

surface of the leaf sucks in moisture and the other gives it out. What

they receive through the upper surface by day they give out through

their under surface at night by a process of evaporation.

When the bulbs are planted the leaves (or fans)are already

pushing forth a green shoot. The gardener does not feel particularly

uneasy if the frost touches the tip of the shoot, but they are very

much afraid of (the frost)its reaching the flower-buds within the

shoot, for if their tops are nipped by the frost, the hyacinths will be

disfigured. If any one or two of the leaf sheaths get yellow or

diseased they can be cut away without injuring the bud, and neither

will the bulb itself suffer, as in any case the leaves drop off in the

end of the year.

It is evident now that Nature works in the bulb from the

interior to the exterior, and this principle must be well borne in mind

by the cultivator.

CHAPTER III. -- YOUNG BULBS

Having thoroughly examined roots, leaves, and tunics, we now

come to the organs of reproduction, and as the young bulbs form them

themselves very oddly and irregularly at the base of the old bulb, it

is very difficult even for a connoisseur to judge whether any little

bulbs are coming, and still less can he foretell how many he may hope

for. Sometimes they are numerous, and on single hyacinths twenty-four

have been known to develop on one bulb, but on single hyacinths they

develop very irregularly, while on the double they are more regular in

their growth; growing from the centre; though, as the central stem with

all its leaves grows, the new little bulbs are pushed more and more to

the sides -- sometimes they push through to the outside of the bulb,

sometimes between the tunics, wherever they can get air.

Each baby bulb contains the same number of (fans) leaves as

the parent shoot, and develops in the same way -- only that the first

flower of the new bulb is very thin and small. The tunics partake of

the same bulbous substance which forms the base of the bulb until it

grows to the height (or point) when it begins to take the suberous

quality which distinguishes the leaves from the bulb substance, and so

the tunics, as far upwards as they partake of the bulb substance,

possess the same capacity of producing young bulbs, which grow from

them in the same manner as from the base.

Some gardeners, in order to multiply their bulbs more

rapidly, perform the following operation: with the point of a penknife

they cut into the base of the bulb (the point turned upwards and

inwards), turning the knife round inside the bulb, the base is cut out

(with crown and centre) in the shape of a cone -- the upper portion

forming a concave, exactly fitting the convex of the base (which is the

interior which has been separated by the knife).

The separated base forms no stem the first year, and the

inner tunic leaves (fans) are little and poor, and seem hardly to have

strength to grow, but they form themselves into tunics quite well, and

are grown enough by the following year to cover the stem, which,

however, is not quite developed as it should be till the third year --

then it is as good as any other of its species. The inferior or lower

part scarcely ever produces young bulbs after it is cut from the rest.

The two parts of the bulb should be carefully put into very

dry sand, covering them about two inches -- they must be left some

little while exposed to the sun, which would burn them if not well

covered with sand: they must then be put in a window or in some place

where they are well preserved from damp; they are thus left for four or

five weeks -- the superior part turned top upwards -- the under part

anyhow, it is a matter of indifference how it is placed. In four or

five weeks' time the upper portion has developed such a number of young

bulbs that they are injuring one another.

The baby bulbs are by this time perfectly formed, and one can

count their leaves or tunic leaves (fans), six or more, and each

possesses its stem. The upper part (of the bulb operated upon),

consisting of tunics without base or crown, which is thus able to

produce so many young bulbs, can also manage to nourish them during

their early growth (though without roots).

This operation will sometimes save a bulb when it is

beginning to decay at the base, and it will thus produce bulbs when the

decayed part has been cut away. The bulb called "l'Eveque" has a way of

bringing forth young bulbs like buds at the base of the flower-stalk --

one or two young bulbs will be found adhering to it an inch or so above

ground. These little bulbs are as well formed as if they had come from

the base and had been nurtured in the earth. Perfect bulbs can be

raised from them by cutting the stem an inch above and an inch below

the part to which the young bulbs are attached; they are then put by in

earth, and treated in the same way as those which had the con/c

operation performed on them; and just as those were grown and nurtured,

simply fed by the tunics -- so these obtain their sap for the first

year entirely at the expense of the stem, and without starting any

roots on their own account. Never more than two bulbs grow thus upon a

stem, while very often nearly thirty appear on the upper part of the

bulb, which has been separated from the lower part (cone shape). The

bulbs grown on the stem take a longer time in coming to perfection than

those that start from the base, as a rule in their first year they seem

to reach to the same stage as a three-year-old bulb which has been

raised from seed -- and follow the same gradual course of development,

not producing a perfect stem in the beginning.

It is a well-known method with gardeners to cut their bulbs

in order to give air and outlet to the young bulbs that are coming.

They are simply sliced across (not very deeply) underneath, at their

base; sometimes they are slit crosswise, good care being taken the

knife does not cut into the growing flower stem in the centre (the

centre of the cross-cuts meeting a little to one side to avoid the

central stem). By this means this year's shoot is preserved, and when

the bulb bursts asunder (along the lines cut for it, through the

strength of the young bulb-shoots pushing their way through) a

principal bulb forms itself in the centre, which by the second year is

as perfect as any.

There is no part of a bulb which can be pointed out as

exclusively serving for the production of young bulbs. They come

sometimes from the centre, sometimes from the stem -- bursting open the

bulb and becoming so like it in form that gardeners have some

difficulty in distinguishing the parent bulb from the new. It seems

inconceivable that Nature should put such strength into such a delicate

production as the young bulb; when once it finds space to develop

itself there is no part of the old bulb it will not force to let it

through. The angular form of the young bulb comes from the kind of

resistance it meets and moulded by the space in which it is free to

expand. If it grows on the outside of the bulb, it is concave on the

side which joins the round side of the bulb, while on its outer side it

is round.

After the first year the young bulb becomes its normal shape,

like those which are raised from seed. It is difficult to ascertain if

a bulb is going to produce young ones or not, -- it is easy to be

mistaken, though the conic operation will show clearly in a few weeks

if young bulbs are going to develop. It seems scarcely possible that

those which develop more naturally can force their way through the

tunics without aid, and do their work in the space of one year,

It has been found that when young bulbs have not strength

sufficient in their first year to burst the tunics, their development

is much assisted by the bulb being cut. The different experiments which

have been made prove convincingly that a bulb can bear many amputations

safely, and if at any time a sickly bulb has to be cut, one may be

pretty certain to get young bulbs from it by taking care to keep

the wound made by the cut quite dry.

There are some bulbs, such as François Ist, which

may exist years without producing a single young bulb, while others

produce at so great a rate that one only wishes they would stop. This

shows that young bulbs are plentiful, and may grow in all parts of a

bulb, -- only that in some they find more resistance than in others, --

and the difficulty they find in working their way through the harder

sorts causes the slight difference in the forms of the bulbs in the

different species. Though all look very much alike to the casual

observer, there are nevertheless differences between them. There are

some famous growers, such as George Voorhelm, who seldom makes a

mistake though he owns 1200 sorts. Each sort has its own regular and

distinctive method of reproduction, and peculiarities which mark one

species never become accidental in another; each kind keeps to its own

manners and customs.

Nature being ever obedient to laws, certain knowledge of her

ways is the more easy to acquire -- the law of species will be the same

in a thousand years as it is to-day. Culture has certainly improved

species, and finished what Nature could not by herself complete. Some

accidents have become thus a second nature, remaining permanent if

another accident does not again occur to disturb the existing order.

CHAPTER IV. -- SEEDS

Although there is a way of propagating hyacinths by seed,

like other plants, yet it should be known to all that it is seldom that

a double hyacinth produces seed, and such a thing has not been known as

a seed (from either double or single hyacinth)ever producing a species

at all resembling the hyacinth from which the seed is taken. "La

Perruque quarrée," a red hyacinth, has produced "La

Comète " -- a very fine sort, and a splendid red, but it has

no resemblance to "La Perruque quarrée," and yet they are

about the nearest in likeness that have been produced. There is no

visible difference between the seeds of double and single hyacinths.

Gardeners are more hopeful of raising double flowers from the seeds of

single hyacinths than of raising double from the seeds of double. They

have not yet found any principle to go upon in the choice of seeds,

however many experiments have been made. Some have thought a

well-formed hyacinth in its seventh year, being then in its prime, is

more likely to produce double flowers from its seed than it would be if

ten or fifteen years older. It is supposed that the seed of a full

hyacinth, which has its petals redoubled to the centre of the flower,

possesses an advantage over others, or double may be raised from its

seed, but it very rarely produces seed at all; when it does, success is

still very uncertain. Some like to try semi-double; some follow one

method, some another, few obtain the same result twice over. Some

amateurs, once upon a time, longing to obtain a new sort of flower,

sowed the seeds of a single yellow hyacinth, very pale in colour, and

of quite a small and common sort; they were lucky enough to obtain

splendid flowers of a very good white, the centre a perfect yellow,

stems and blossoms all superb, -- " Saturne," "Heroine," "Flavo

Superbe." "Og Roi de Basan" also derives its origin from the stock

raised from this seed.

Countless experiments have been made, and all tend to show

that flowers produced from seed never resemble the flower from which

the seed was taken. As a rule they differ in every point, shape,

colour, and height. Nature insists so much on variety that even seeds

taken from the same seed-vessel do not produce flowers alike. Some may

be red, others blue or white, large or small, as the case may be,

sometimes they are fortunate enough to get several double varieties

from the seed of the single hyacinth. It must be confessed, added to

other difficulties there is this: it is four years before the seed

produces its flower -- that is, in an ordinary way, for sometimes it is

more advanced by one or two years. As during the course of four years

the bulbs are taken up three times out of the ground, it may sometimes

happen that the experiment has failed through negligence, but there has

never been any doubt at all about the fact of a seed never producing

the same kind of hyacinth as the parent stock.

One should not cut the hyacinth stalk, or separate it from

the bulb, if seeds are to be taken from it, until the ovaries are

yellow and beginning to open and show their seeds, which should be

already black. Then they can be cut and put in a place where they are

protected from sun and rain, and when the ovaries are quite dry the

seed can be taken from them and very carefully kept (not wrapped up or

covered) until the time for sowing them, about the middle of October.

Growers who have no interest in preserving the seed believe it is a bad

thing to exhaust their bulbs by leaving the seed to ripen on the plant.

The earth that the seeds are thrown upon should be well prepared (I

shall describe its composition presently).

The seed is visible enough to be spread about without the

necessity of mixing it with sand, as is sometimes done with vegetable

garden seeds. They must not be sown too thick, and about an inch deep.

When it is beginning to turn cold they must be protected from the frost

by a covering of manure, leaves, or tan. The seed, which begins soon to

germinate, is very sensitive to heat and cold. The parts of the seed

are not unlike a fruit. It is first covered by a strong black skin, and

under this a fleshy substance. This contains an almond, within which is

enclosed the germ; this develops in the same manner as in the seeds of

all plants that are called by botanists "one lobed" or "monocotyledon."

During growth this almond part of the seed detaches itself from its

wraps.

When the grain is put into the ground in the month of October it

swells, and the germ, piercing through the pericarp

or fleshy part of the seed, begins to develop itself. The little leafy

shoot which pushes upward is the part that botanists call the plumule,

and the part which pushes from the central axis (or planrule)is called

the radicle or little root. During the first year the little root is

always tuberous or knotted. It does not yet draw sap from the earth. It

is generally agreed among botanists that the plumule and radicle (the

plant and little root) at this stage draw their nourishment from the

cotyledon or seed-lobe, to which they are still joined. This lobe goes

on nourishing the plant till the bulb has already taken form, and takes

in nourishment from the earth (through its base).

The thin round leaf-shoot which comes up

remains bent a

whole year before it has gained sufficient strength to rise straight.

The first year the root is only a thin thread; sometimes it grows very

long and is full of knots, then it is organically diseased, and the

bulb will be very weak and worthless. They often die when the root is

thus deformed. To make a well-formed bulb the root should have only one

knot at the place where it comes from the seed; upon this the bulb

forms itself. At first it is composed of a single tunic, and this tunic

is joined and completely closed on all sides.

At the end of one year (after sowing the seed), if the bulb

were taken up, one would find this tunic lined with two other tunics

exactly like it.

The bulbs being still very small, they exhaust the soil very

little, so that the first year growers do not take the trouble to take

them up. But an amateur, who raised a great many from seed, used to say

he thought taking them up every year certainly assisted their growth.

After it has been eighteen months in the ground the bulb has

gained a certain consistency; it is now composed of four tunics, each

of which encloses it entirely, the outside tunic appearing brown and

dry (as if the drying process had begun, for this outer one has to

shrivel away in the earth next year). The leaf-shoot still looks thin

and round like a rush, but it holds itself straight, and has gathered

strength since last year. The second year (about the time it has to be

taken up) it has lost its outside tunic, but has still three left,

completely surrounding it, but within the inmost envelope the base of

the leaf-shoot or fan (which now shows a double shoot) is already

spreading and forming in the centre of the bulb a tunic, like the

tunics of the proper (grown) bulb; that is to say, it wraps it only

two-thirds of the way round its circumference. The roots have now

strengthened. The following year they are yet stronger. The bulb casts

off all its binders, the early tunics which enveloped it completely

(like a bandage). After this it enters into its mature state, the

leaves, instead of clinging together like a round rush, separate,

slowly detaching themselves and taking the shape they are to preserve

to the end, though every year they increase considerably.

From the time the bulb loses its first closed tunics it is

able to produce its flower, which it never can do while it remains with

closed tunics. The first flower has a long feeble stem, which bears

one, two, or three small blossoms, but these are enough to show the

sort of flower it is going to be. If it is single it will remain a

single always, neither will its colour vary again, and it can be

classed among the red, blue, or white of its kind, but it will grow

more perfect and improve in height, size, and colour. If the flower

turns out to be double, the growers are delighted, and then they will

spare no pains in developing its beauty, for they know not what degree

of perfection it may yet attain.

When the bulb is three

years old (having a treble shoot, and having lost its last completely

enveloping tunic) it possesses only the ordinary tunics, which are

formed by the expansion at the base of the leaves (these envelop only

two-thirds of the bulb).

The bulb, when four

years old (having developed more perfect leaves and begun to produce

flowers), is composed of about twenty tunics.

If the flower, during the

fifth

year, continues to develop and shows to advantage in colour, form,

etc., the growers' hopes rise higher still, but they cannot tell even

yet if the flower will fulfil its great promise.

A bulb which has grown too rapidly will sometimes throw out

young bulbs (or offshoots) at four or five years old, but never before

it has once,

during the course of its life, put forth a flower. This fact is

important to remember in regard to observations to be made later on, on

the subject of vegetation.

In the ordinary course of nature the bulb does not arrive at

its final state of perfection until its seventh year. The grower

delights to note its yearly growth in grace and beauty, till at length

it becomes précieuse,

then he is fully repaid his care, and the kind is for ever fixed, and

will never vary again, and it will produce young bulbs which will, in

their turn, produce again, and all will perfectly resemble their first

parent bulb (though it has happened very seldom indeed that flowers

have changed in colour, but this will be explained).

Growers call the flowers they obtain by raising from seed

"Conquests." They share and exchange among themselves these seeds of

promise, and sell to each other the third quarter or half of the bulb

productions, which, however, should not be parted with unless there are

a certain number of young bulbs to be divided. The prices they pay for

these invaluable seedlings would astonish an amateur. They enhance the

value of the bulb, for which the fixed price is sometimes above 1000

florins. Some are worth as much again. Growers usually keep notes of

the origin and date of bulbs.

Some hundred years ago double hyacinths were thought little

of; they were almost unknown. Swertius, in 1620, gives a list of about

forty kinds of hyacinths; none of them were double. The gardens of

George Voorhelm belonged also to his grandfather, who had already tried

raising hyacinths from seed, and whenever he made a Conquest, Pierre

Voorhelm would reject any which seemed out of the ordinary, or out of

proportion to the rest of his flowers, for in those days they took a

pride in the formal and regular arrangements of their flower-beds. He

took care, especially, to destroy double hyacinths when they appeared,

without waiting to see what they might become if they were allowed to

develop. He was only anxious to keep flowers which promised seed. It is

certain that double flowers have not a seed-bearing quality; they are

not formed for maturing the seed enclosed in the ovary, so that any

flower without this particular good quality did not fail to be

rejected. No one took the least pleasure in the idea of a double

hyacinth; it was rather regarded as a monster (or freak of nature),

just as at the present day nobody cares for a double tulip.

Pierre Voorhelm fell ill, and being quite unable to visit or

attend to his plants until the hyacinth season was nearly over, he

happened then to see a double hyacinth (the kind is now lost) which had

been forgotten, and had not been thrown away as usual; it was very

small, and he only liked it because it seemed to match very well with

the single ones -- so he cultivated it with the rest and obtained bulbs

from it. He found it was much admired by amateurs, who were ready to

pay a good price for it. So he took to cultivating the double as well

as the single, and soon began to be as anxious to find them among

"Conquests" as before he was to get rid of them.

Of the double species the first known was named "Marie," this

and the two kinds that followed are now lost. "Le Roi de la grande

Bretagne" existed only seventy years -- this was rare and much sought

after, and the price rose to many thousand florins. This bulb, imported

to hot climates, grew infinitely better than in Haarlem; for it soon

died in cold or damp spots. From this time great attention began to be

paid to the cultivation of hyacinths raised from seed.

The number of "Conquests" has now become immense, and many

more grow bulbs than in former days, and every grower makes his own

catalogue, in which his "Conquests" are known under names which are

kept in all the lists which are re-written every year. In this list

there may be flowers of different colour bearing the same name -- such

as "Gloria Mundi," which is classed with the blues; the same name

re-occurs classed with reds and whites. Frequently double-flowering

bulbs of different colour have the same name -- so that it is as well,

when ordering a particular bulb, to specify and enter into details when

writing the order. Then mistakes will be prevented, which are as

distasteful to the grower as to the dissatisfied purchaser. Growers do

not all agree in classing their bulbs, some for example classing among

reds a hyacinth which another would call white with red heart,

and which a third might call pink and white, or flesh colour. Besides

which the exact shade or nuance

differs perhaps in every garden -- and it is not so easy to class

hyacinths in a way to satisfy everyone, any more than it is easy to

produce a completely satisfactory Method of Botany. Seasons are

variable, and colours of flowers are much affected by changes of

weather. 1767 was g very disastrous season by reason of the cold north

wind which prevailed in the early part of the year. Red hyacinths were

infinitely poorer than the preceding year, which was a particularly

favourable one to bulb growers.

One must make allowances for seasons and accidents, and one

ought not to expect the bulbs sent off annually by the growers to be

always equally good, for in some years they are more successful than in

others -- also the same bulb which flowers splendidly, as a rule, may

take it into its head to yield' a very poor flower, though it may be

planted in the same soil -- between two others which are doing their

best; one can see no cause why they should be so uncertain, except

perhaps they pump in sap more vigorously at one time than another. It

can be accounted for Sometimes by the fact that the bulb itself is

feeling disposed to throw out young bulbs, and the sap is being drawn

away from the flower-stalk -- or it may have suffered from a cold

draught, when it was lying on the shelf in the winter -- or it may be

it is feeling the damp.

CHAPTER V. -- ORGANS OF

REPRODUCTION

The various species of hyacinths, though apparently different

and distinct, are essentially alike. Bulbs of one sort differ very

little from those of another -- the leaves are always alike, their

stalks grow in the same way -- their blossoms, though infinitely

varied, are arranged in the same regular order -- each connected with

the stem by a little thread, called the pedicel.3 The

double scarcely differs from the single, except in the blossom. We have

already followed the gradual course of the growth of the bulb, and

described its general composition. We will now go back to the single

hyacinth, for in explaining its work of reproduction it is easier and

more convenient to dissect than the double flower.

The calyx or corolla forms at the base (through its shape) a

chamber or room in which the "ovary" is found, but detached from it. At

the point where the calyx is narrowed in at the entrance of the ovary

chamber are the stamens. The parts of the corolla (or divided sections

which curl back in the hyacinth) are called petals.

The stamens are attached to the interior of the calyx, and

from the base of the stamen to the pedicel (or little connecting stalk)

runs a fine fibre (which takes the place of the filament which is

detached in other flowers), and this is seen from the outside as a line

of colour a little darker than the rest of the flower.

The ovary (in

the chamber at the bottom of the calyx) is surmounted by the pistil,

the narrow body of the pistil is called the stylus, and the head is the

stigma.

The stamens of the hyacinth have no filaments, they are

sessile within the calyx, and the anthers are also attached at their

base (though there is the fine thread of darker colour to be seen

running through the calyx extending from the stamen to the pedicel).

The stamen is covered, when ripe, with a

yellow dust called pollen,

this looks like little black grains when under a microscope -- they are

little bags full of a kind of clear juice, these, when the stamens bend

over and shed (as pollen), are caught by the stigma at the head of the

pistil. This stigma, when seen under a microscope, is seen to be

composed of very fine valvular cells, which can hold the seminal

juice-the juice passes through the narrow channel of the stylus (or

body of the pistil) into the centre of the ovary, which has an aperture

so arranged as to let it in till it is full, when it closes again so

completely that the seminal juice is held within till the time comes

when the ovary is forced open by the ripening seed.

Before the flowers expand, and while they are still enveloped

like a wheat ear in leafy bandages, the ovary is already furnished with

eggs; but the seminal juice has not yet been deposited, the pistil not

being formed enough to open its cells, but even while the flower is

still in bud, the anthers let fall their pollen, and the pistil opens

its cells, and no one seems to know exactly when it happens that the

pollen explodes its little capsules of liquor or vapour or breath,

which form the seminal juice.

Saint-Simon has a theory that the bees flying to and fro

constantly over the flowers disturb the pollen, often carrying with

them some of the pollen (containing seminal juice) from one flower to

another, where it is deposited and received through the pistil into the

ovary, and he suggests that this is the Cause why "Conquests" (i.e.

hyacinths raised from seed) never bear any resemblance to the flower

their seed is derived from. But this does not seem entirely to account

for their infinite variety. The invariability of this rule (that no

hyacinth has been known to produce its like by seed) seems to prove

that variation is not subject entirely to accidents of this kind, for

surely sometimes by accident there would come up the same flower as

that from which the seed was taken. Some growers may have taken seed

from hyacinths grown in hothouses, where the flower has been protected

from bees and butterflies, and thus undisturbed the flower should have

had seed which reproduced its own kind -- and why should this occur as

an invariable rule among hyacinths, when other flowers more frequently

reproduce their own kind than not, with them the variation (when

their seed has been crossed by insects) is an accident.4

Curious experiments have been made with

hyacinths.

Two different bulbs are to be chosen, blue and white, for

instance. Cut them perpendicularly down nearly through the middle, but

being careful to avoid cutting into their central shoots (i.e. the

future flower-stalk), then join together the two larger halves

containing the flower-shoot, thus making one bulb of them, so that the

two flowers should appear as arising from one bulb. Then, with a little

moss wound round the closed joins, the made-up bulb may be put into the

earth like any other. This usually results in producing two stems stuck

together back to back, with one skin around them both apparently; and

on one side comes out white flowers, on the other red or blue.

Sometimes the colours get mixed, the colour of one flower shaded with

that of the other, very rarely do the stems grow separate.

None of these experiments seem to explain how it is that a

single hyacinth can produce a double (by seed raising), though perhaps

in ten thousand seeds only two or three will come up double flowered;

nor how it is that the double can be redoubled (through seed), and that

once redoubled, the bulb is constant in giving off young bulbs with

double flowers, which never again degenerate into single; nor will a

single, in its offshoots, ever become a double hyacinth.

CHAPTER VI. -- GENERAL

In the cultivation of hyacinths it is impossible to keep to

any fixed rule. Not only must every country and climate make its own,

but every hyacinth has its own ways and customs, its own special

qualities and characteristics. The most distinguished of their species

exact a great deal of attention, care, and management.

"François Ist" finds great difficulty in producing

offshoots, and great care has to be taken of the young bulb, but when

once arrived at full growth it is not as subject to disease of various

kinds as are other bulbs, and it does not die easily. It is the only

bulb that still continued to command a high price twenty-five years

after its first appearance; 100 florins were paid for a single bulb.

"Rien ne me Surpasse" is one of the most perfect blue, but it

has such wretched, weak, faded, even crumpled leaves, one would think

the poor thing was ill, but notwithstanding it produces a handsome,

healthy-looking flower.

"Passe non plus ultra" also looks very deplorable as to its

leaves, they seem hardly able to hold up, and remain lying flat upon

the ground, though quite green and well.

On the other hand, "Og Roi de Basan" shoots up its leaves so straight

and tall, and so large, that they seem quite out of proportion to

others, and the flower is an extraordinary height, overtopping all the

rest. The "Theatre-Italien" is a good red, but it grows very short, and

comes out before its leaves, so that its head may be nipped by the

frost.

"Marquise de Bonnac" is a very delicate colour, but it gives

way in the stem before the flower is fully out. The stems seems to fade

and dry up, and the flower falls on its face, and this is a very

tiresome habit. But it does not seem to damage the bulb, which flowers

regularly every year, notwithstanding these little accidents. A famous

florist told me it was because it had a bad circulation, and the sap

hung on the sides of the bulb, instead of running up the stalk.

"Alcibiades' and

"Beau-regard" are also subject to such accidents; but they

can be prevented by planting the bulbs in November, that is, a month

later than other sorts. These kinds give off a number of young bulbs.

The bulbs which multiply very little and slowly have generally better

constitutions, and do not perish so easily. White, with red, purple, or

violet hearts are very subject to decay. "Gloria Florum Suprema"

perishes easily, and its offshoots perish with it, and this is peculiar

to this hyacinth, for most of those that perish easily also multiply

quickly. The kind that multiply fast are generally furnished with more

roots than the others.

Growers are mostly agreed that bulbs succeed infinitely

better if taken up from the ground every year (though it does seem

contrary to nature). It often happens that a bulb, if left in the

ground, does admirably the first and second years, and sometimes a

third year it does well, but after this period it usually catches some

disease which turns into an epidemic, killing all the bulbs in its

neighbourhood; it is too late then to find a remedy, and if lifted it

will only rot on the shelves, as it would have done in the earth. One

knows insects are more numerous one year than another, and thus they

too may cause epidemics.

Lifting the bulb

is also a method of preserving the young bulb, which otherwise would

perish and decay from damp if left all the year round -- or, as they

are sometimes a foot or more below ground, they effort they make to

force their shoots through that depth of earth is too much for them.

It has been observed that when the sap does not circulate

freely in the bulb it is drawn up into the stem, and this is sometimes

occasioned by overheating the room or greenhouse, -- then it grows tall

and weakly, the flowers are thin and deformed. The more the channels

through which the sap runs into the stem are dilated by too much heat,

the tighter they close again when the sap has finished its action, and

the bulb becomes thinner than it should be, and it is exhausted for the

next year's growth and appears very languishing. One can see very well

how this comes to pass when it is remembered that the next year's

flower is actually contained in the base of this year's stem, therefore

what weakens one weakens the other. If the bulb is very deep in the

earth and the ground is hard, it cannot spread and enlarge itself with

comfort, so the health of the bulb requires it to be lifted every year.

Besides the necessity of separating

and preserving the young bulbs which have to be replanted, there is yet

another advantage to be gained in lifting, for then there is an

opportunity of taking away decayed bulbs before the disease is

able to spread further through contact with others.

Having given some ideas on the cultivation of hyacinths in

general, perhaps it is as well to give in some detail an account of the

particular (or individual) care and attention bestowed upon their bulbs

by the Haarlem growers, and perhaps some hyacinth lovers may feel drawn

to imitate their spirit. Haply if they meet with the same difficulties

they may benefit by their experience and observations, and thus

obstacles may be surmounted that stand in the way of the development of

the ideal flower. These obstacles are often the result of soil,

climate, and inexperience.

As a general rule, hyacinths require a light soil, which

easily lets the water run through, but at the same time such a soil is

soon washed out, and it thus in a short time loses its good qualities

and richness. The sulphurous and oily qualities in the soil, that the

hyacinth delights abundantly to suck out of the earth, would be washed

away or evaporate speedily in such soil, even if the bulb itself did

not actually exhaust the spot where it has grown, this is the chief

reason why growers change their bulbs year by year. Damp is death to

bulbs. In a damp soil bulbs can never be preserved for any length of

time. The two general rules, --

Choice of light soil, Avoidance of damp,

are the very foundations of bulb culture. The "couches" or "beds" made

by florists for their finest hyacinths are remade every year, they are

also protected by caisses and layers of manure from the cold in winter,

and they are shaded from the hot sun in spring by canvas awnings. The

old soil (taken from the hyacinth beds) is carried to the garden

borders, where other flowers are grown, such as tulips, lilies,

Fritillaries, etc. The following year hyacinths are replaced in these

borders, and succeed therein marvellously, -- thus year by year the

same earth bears alternately hyacinths and other flowers. If the

reader's patience is not exhausted entirely I must ask him to bear out

a little longer, for I cannot without entering into very minute details

give any intelligible idea of the qualities necessary to provide the

sap with the kind of nourishment it seeks in the soil after the bulb is

put into the ground.

In Haarlem they take two years to prepare the compost, or

composed soil, which suits hyacinths so well. The first year a store of

leaves are gathered together and laid in considerable heaps, so large

that while they are rotting and becoming fit for use the sun cannot

penetrate, for if they were spread about the sun would cause the salts

and oils contained in the decayed leaves to evaporate, for this reason

the heaps are not to be in places where they are exposed to the sun,

nor in a damp place where water can sink in or stagnate. Growers do not

gather in all kinds of leaves, they have observed that oak, chestnut,

beech, and the leaves of the plane tree (which is now becoming common

in Holland), and others of like nature, do not dissolve easily into

earth; while the leaves of elm, wych-elm and birch, etc., are chosen

because their loose and fibrous tissue dissolve more readily into soil.

In the same manner they lay up a heap of

cow-manure, which is left to ferment en masse.

Every country has its customs, and the Dutch customs make a real

difference in the quality of the materials employed. All over Holland

cows are kept in stalls from November to May only, and during this

tithe they do not eat grass. All the summer they remain in the open,

night and day, in the fields, so that manure is not kept or taken up in

the summer months. In the winter, when the cows are fed on nothing but

dry food, the manure is of quite another quality from the summer

manure, when cows have grass. This may be useful to note for those who

live in countries where manure is kept all the year round. Cows are

tethered in stalls in so narrow a compass that one can hardly conceive

how they can exist like this. They stand on a kind of platform between

two trenches, before and behind them; in the front trench their food is

put, which they can only get at by pushing their heads between boards,

which also prevent them from reaching too far and pulling out the food,

where it would be trampled under their feet. The second trench, which

is deeper, is behind them to receive the manure, which is taken away

and heaped up in a dry place, where it can easily drain and where the

rain can also run off, for no water or wet is allowed to settle in or

near the heap. As no straw whatever enters into the composition of this

manure, it is not at all like the kind collected in other countries. I

do not know if this is the reason, or why it is that in England,

especially round London, hyacinth growers avoid using cow-manure as

much as possible, the soil there being so stiff and rich that it suits

them better to make it a little poorer, with an admixture of sand, than

to heat it even with cow-manure, which is the lightest kind of manure

there is. First a heap of leaf-manure, a second heap of cow-manure, and

a third heap of sand is now made of sand brought from the dunes, or it

can be dug out of the very ground beneath to the depth of some feet.

Though all the soil about Haarlem and its neighbourhood is mainly sand,

especially near the dunes, where most of the bulb fields are, yet they

prefer to fetch sand from a distance rather than take any from the

surface of their own ground. This sand should be as carefully examined

as is the manure, so that, now that I think of it, I must enter into

further details, which will be thought unnecessary by some people, but

others will be glad to follow the spirit of our inquiry.

The nature of the soil in Holland proves that the country has

undergone great geological changes, apart from the continual

encroachments of the sea.

It seems that at a very distant period, perhaps before or

after the Deluge, the country must have been covered over with forests,

as were Germany and Gaul in later times.

Either in the great Deluge of Sacred Writ, or during one of

the partial deluges that men of science speak of (but of which no one

seems to have any positive knowledge), these trees must have been

thrown down and laid on the ground in the direction of east to west, in

such a manner that where they fell they form strata (or layers), which

time has reduced to a thickness of six or eight inches at the most.

It may be that this layer of trees was at first exposed to

the air, or (as is more likely) was for some time covered by the sea,

which, depositing sand, pressed and consolidated it into the mass which

we now see, and which is found in all parts of Holland and Zealand, and

is known under the name of Darry or Derry.

It is very easy to perceive that it is old wood decayed into

the earth and reduced to the loose consistency of a sort of brown

charred coal. In some parts bits of the wood have been preserved whole

and unchanged.

In the Bailey of Amstelveen, near Amsterdam, bits of wood are

often disinterred which has still "heart" enough to be used as ordinary

wood. Between Alphen and Leyden are to be found in several places whole

tree trunks, ten or twelve feet long. The derry matter is very

substantial, and it is very inflammable; it also holds water, so that

it does not run through from the surface of the peat to the water in

the soil below it. In Zealand, where it is easily taken up, it is

forbidden under penalty of death5 to carry away the peat,

because the water underneath, which it retains, would do considerable

damage in the island.

As we now know that piles and blocks of wood can last 2000

years in the earth without rotting, so we may conclude that these trees

(which now compose the derry or turf) must have been much longer

undergoing the various operations of nature which resulted in producing

this change. No tree roots can penetrate this derry, and wherever sand

does not cover it over a certain depth, no vegetation can grow. Water

falling on the peat is held there, having no means of escape, and the

sand on the top is, therefore, always moist and fresh in proportion as

it is near the derry. If one digs a little hole in this ground, the

water which "fattens" the sand collects in a moment and fills up the

hole which has been made, and this becomes a running spring. These sort

of springs exist all over Holland, and they generally go by the name of

sand-wells. They are kept supplied only by rain, or by the water which

filters down through the sand from the dunes, and this often to a great

distance.

If bulb roots were to reach down to within a foot of this

layer of peat they would be spoilt, and the bulbs would perish. The

depth of the sand-layer over the peat is unequal and different in

parts. By measuring it they test the value of the ground, and not less

is the value measured by the length of time the sea has withdrawn from

the surface. There is no doubt this sand is from the sea-bottom,

whether it was the sea's action that brought it, or whether it has been

blown and driven by the wind. The dunes have so often shifted that a

knowledge of the variations due to the shifting of the sand in the

dunes is enough to account for sand-layers, for it can be driven very

far indeed by wind from the sea.

A little while ago the village of Sheveling, near the Hague,

was surrounded by the dunes, which were at that time some distance from

the church, now it is much nearer, the church cannot have moved. On the

same coast the mouth of the Rhine has been choked with sand, and the

sea now covers the castle of Bret, facing Catwick-sur-Mer. The castle

can still be seen at certain seasons at low tide. The sea has remade

other dunes, half a league farther inland. All along the coast near

Haarlem, beyond the canal which connects Haarlem with Leyden, the main

road cuts through these dunes in several places. In the island of

Walcheren, in Zealand, at very low tide can be seen vestiges of the

ancient town of Domburg, where they fish up statues of Nehellenia, a

heathen goddess, and also early Roman inscriptions.

In the present day dunes 100 feet high separate the new

Domburg from the one invaded by the sea, and the Zealanders, through

their marvellous and inventive industry, have succeeded not only in

fortifying themselves against encroachments from the sea, but have made

very extraordinary dykes, like the one at West Cappel, which you cannot

see when you are standing upon it, as it is nothing but a very long

sloping bank or glacis of timberwork, but the slope is so gradual that

the only resistance the water meets with is the long journey it has to

go to reach to the summit of the dyke, which, at its level, is much

higher than the sea.6

But besides this they covered miles of the sea-shore with platted straw

matting, which they plat on the shore itself, -- this is to prevent the

sea from carrying the sand away from its own shores. These mats have to

be renewed almost yearly.

The sands of Haarlem are all more or less of this nature, and

contain saline and sulphurous particles of matter; the under stratum of

peat or derry prevent these from being absorbed into the ground. The

sand also contains particles which collect in some places and form a

very thin stratum of hard black matter, like that with which some

minerals are coated, and this is not less injurious to vegetation than

is the derry.

The great success the Dutch growers have had in cultivating

bulbs which cannot be successfully propagated elsewhere is very much

due to the presence of this sand, deposited by the sea on a matter

which, fortunately, water cannot penetrate.

To return to the three heaps, -- sand, cow-manure, and

leaf-mould, -- the sand is placed in large heaps to "ripen," rather

perhaps to lose some of the moisture. The growers from the three

compose one general mass, which they arrange in the following order:

First, they make a layer of sand; second, of manure; and third,

of leaf-mould eight or ten inches deep; they then begin again making

more layers in the same order, until their mass is six to seven feet

high. The last layer is manure, but as this is apt to harden in the

sun, they throw a little sand on the top. When this compound has

fermented, six months, sometimes rather longer, it is mixed up and

another heap is made, which is, however, again unmade and thoroughly

remixed. When this soil has remained a few weeks to settle, it is

carried to the beds, where it is laid to the depth of something like

three feet.

George Voorhelm, in his book upon hyacinth culture, says that

this manure should be composed of

three-sixths of cow-manure, two-thirds of sand, and one-sixth

of leaf-mould or of tan, and he for his part preferred fresh manure to

that which had been kept a year (to ferment?). He especially warns

amateurs against using horse, mule, pig, or sheep manures; also he

cautions them against using mud or cold earth drawn from wells, or

basins where the standing water and mud have to be occasionally cleaned

out; also against any powdered stuff or manures picked up with dust

from the street. He quotes persons who compose their soil of tan (which

has already been in use and nearly lost its heat) with cow-manure and

leaf-mould, using no sand at all.

When the soil is brought to the flower-beds they put the said

quantity beneath the bulbs, making the earth quite flat and even,

without pressure, and placing the bulbs upon the earth, not

embedding them.

Then they are looked over to see that the bulbs are arranged in the

proper order or according to diagrams marked out for them. When their

places have been fixed, more soil is brought to put over them, great

care being taken to let the earth fall lightly on the bulbs, not to

disturb their position. The last addition of earth is generally not

more than three to four inches deep. In cases where the bulb has to be

brought forward in its growth, or else kept back -- and is therefore

put at a greater or lesser depth in the earth -- the gardener, in the

latter case, places more soil under the bulb to raise it higher, and

this is a much better method of putting in bulbs than making a hole

with a dibble, or, as some do, thrusting the bulb itself into the earth

with no tool and raking some earth over it, for this plan, besides

hardening the earth all round the bulb (the hole forming a sort of

gutter which holds water!) also runs a risk of bursting the bulb, which

may be already showing roots, or young bulbs hidden within might be

knocked off without its being perceived. The same method is used in

planting bulbs in garden borders. The surface of the earth is taken off

and laid on one side, the bulbs are placed in rows, and are very

carefully re-covered with the soil which was laid upon the side.

The frames used over show flower-beds should be raised not

more than a foot above the earth, and not less than half a foot. If too

high, the air dries the roots; if too low, the damp (from the vapour)

may reach them. The back of the frame should be buried rather deep, so

that when it is necessary to cover the flowers with planks, the frame

will be able to support them, or planks must be put at the back and

sides, fitting into each other, upon which those which form the roof

over the flowers can rest. The frames should be slanting from the back

downwards to the front, to let the rain run off and prevent it from

dripping into the bed. If the cold is very intense, the planks may be

covered with manure to prevent the frost from penetrating beneath. If

the season is a fair one, the flowers may be given a little air; but in

cold seasons it is a risky thing to do, because the early bedding

plants are exceedingly tender, and the heat of the manure, or whatever

is provided to shelter them from cold air, causes a damp vapour to rise

inside the frames, and as this cannot evaporate it falls back upon the

flowers, covering them with a little dew, which, if the cold air were

admitted, would freeze directly. It only takes an instant for young

buds to freeze, then the flowers come out, looking dried up, with burnt

tips. When the cold weather is past the manure is taken off, and air is

admitted to the beds for a few hours in the daytime, care being taken

to cover up again at nightfall. The manure which serves to protect the

bulbs from frost also brings forward young shoots, so that they begin

to show earlier in hot-beds than in garden borders. The slowest and

latest sorts begin the earliest to sprout. They are therefore purposely

not planted so deep in the ground, that they may get more quickly

warmed by sun and air, so it is quite natural that their buds should

pierce through earlier -- but the difficulty the sap has in penetrating

and circulating through the very compact structure of these bulbs makes

it very difficult to get them to flower in good time with other sorts.

Growers have to use their skill not only in guarding flowers which are

beginning to show from frost, but also from strong winds, damp, and

everything that can do them injury. One year rats carried away and

stored by hundreds in their holes the bulbs in the gardens of Van

Zomped at Overween, -- although they had a stream to cross to get at

them. Growers must be

au fait with

every possible eventuality, and must foresee and prevent every possible

mischief. They must know exactly the time by night or day when it is

proper to cover or uncover their flower-beds. Their chosen blooms are

covered with tents of canvas, beneath which they can conveniently walk.

Besides these tents, over the most delicately-complexioned

flowers little parasols are arranged. These are mounted on little rods,

which stick in the ground, and quite protect the flowers, which last

several days longer with growers who give them this protection, and

keep their colour better. When the flowers first begin to expand, our

florists (who work on the principle of never watering) protect them

from rain as carefully as they do auriculas. When they begin to make a

show of blossoms they powder the sand-beds with a light mould, in order

to make the colours look more brilliant against the dark brown

background. They tie the stalks to little wire rods, painted green,