| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER X AMERICAN PEWTERERS AND BRASIERS PEWTER ware, of both American and foreign manufacture, was very common in this country from 160 to 1800. In fact, it was in more general use here, particularly in the rural sections where the people could not afford much silver, than it was in England. After 1780, and especially after 1800, there was a tendency to vary the alloy, so that much of the later ware cannot be classed as genuine pewter. By 1825 its use had been practically superseded by china and britannia ware, though it was made in limited quantity as late as 1840, not to mention the modern reproductions. Pewter is an alloy, the chief ingredient of which is tin, with usually a fairly large percentage of lead, though copper and other metals were used to some extent. There was no Pewterers' Company or other guild in this country to control the manufacture, but the alloy was much the same as that required in England. A more detailed description of the material and the processes of manufacture is hardly necessary in the present discussion.

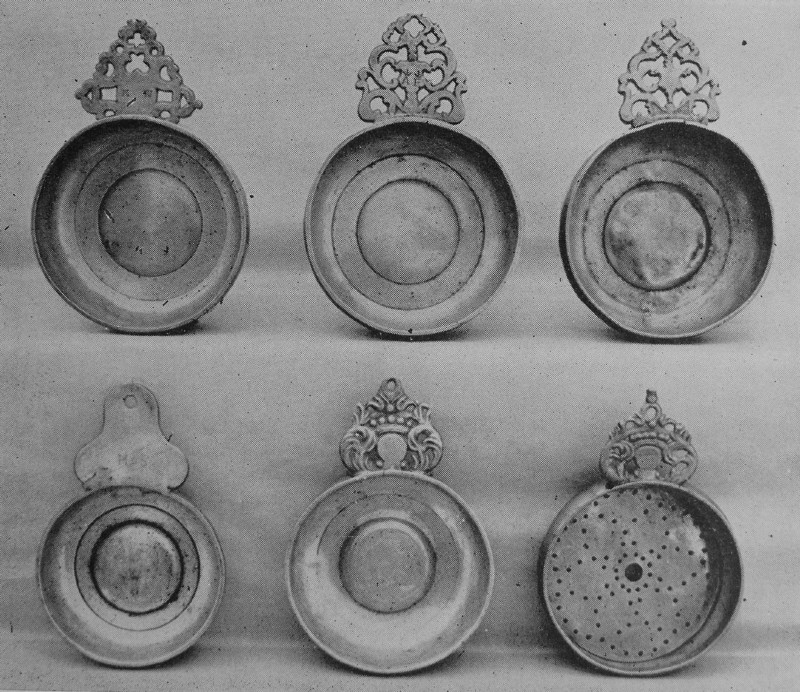

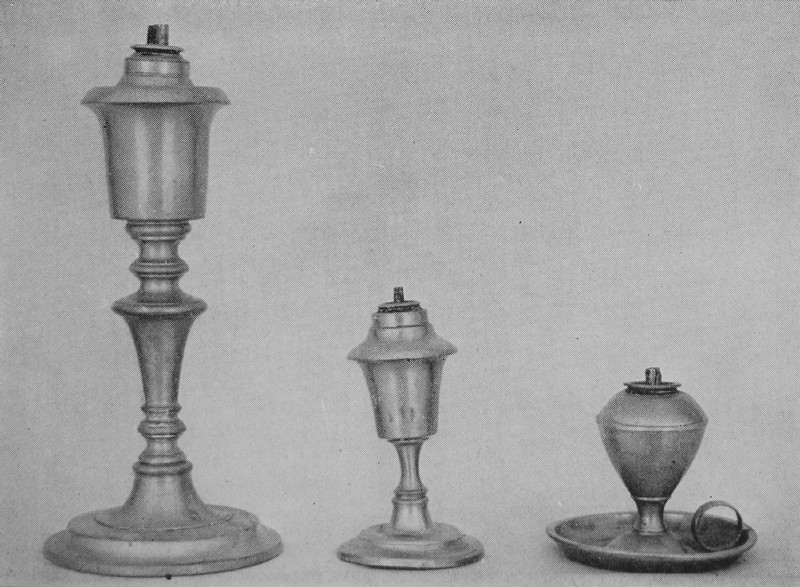

The forms and styles employed by American pewterers followed, in general, those of their English contemporaries. Much pewter was imported from England and it was natural for the American makers to follow its style. It is not unlikely, even, that some of our craftsmen used molds imported from England. But a few of them did add the personal touch and developed something approaching an American style. In general, pewter does not lend itself to ornate ness, and the plainer, simpler forms, recognizing the limitations of the material, are the best. Those which attempted to ape the current styles in silver failed of their purpose. The best of the American pewterers understood this, and their work, as represented by the plainer candlesticks, plates, mugs, etc., often shows a fine appreciation of form and finish and the artistic possibilities of the medium in which they worked. The earlier ware, with its hammer marks, its hand made look, and its soft luster, appeals most strongly to the collector. As the alloy deteriorated after 1780, so did the forms, becoming slenderer but displaying less of the robust grace characteristic of good pewter. All sorts of domestic utensils and many other articles were made of pewter. There were beakers, tankards, flagons, caudle-cups, mugs or cans, measures, pitchers, bowls, plates, platters, porringers, sometimes called posset-cups or posnets, ewers, basins, candlesticks, and candle molds. Betty lamps and rush lamps were usually made of brass, but pewter lamps for whale oil or camphine were common. Pewter salt cellars appear to have been some what rare here, but pewter pepper shakers are some times to be found. Old pewter teapots are very rare. They were probably not entirely successful because they would not stand the heat, and most of those to be found are of some harder alloy of a later date. Pewter spoons were common and followed in the main the contemporary shapes of silver spoons. Pewter was not a rigid enough material for forks. Pewter

communion services were used to some extent in country churches,

though much less than in Scotland. A little of this ecclesiastical

ware is still treasured, but most of it was made after 1780 and is

not pure pewter.

In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries much of the household pewter was made not by professional pewterers, but was cast in molds, more or less crudely, by various individuals. There were a few pewterers here as early as the seventeenth century, however, chiefly English craftsmen who settled in Boston, Salem, Plymouth, and, somewhat later, in New York. By the middle of the eighteenth century there were native craftsmen at work in all the larger cities. The early American pewterers followed the English custom of impressing a touch or trade-mark on their ware, the eagle being a favorite emblem. Often, though not always, this was accompanied by the maker's name. The earlier touches are generally the clearest and best. The later pewterers often used only the name, and many American pieces hear no mark at all. It is therefore often difficult to deter mine age, maker, or authenticity. No one name stands out as that of the master pewterer of the period, as is the case in some of the other crafts, and there were doubtless many skilled craftsmen whose names have been lost to us entirely. Mr. Edwards J. Gale has compiled the longest list, and that contains only forty-four names, dating from 1650 to 1825, and must of necessity be very incomplete. We know less about these pewterers than about the silversmiths. For one thing, theirs was a humbler and less remunerative trade. But there are a few whose names deserve to be permanently recorded. At first Boston was the principal seat of the manufacture and distribution of pewter, but by the middle of the eighteenth century New York had become a close rival and there were other places where the trade flourished. Mr. Gale gives the names of twenty-one New York pewterers and only fourteen Bostonians, but that is partly because of the accessibility of the New York names in the city directories of 1786 and after. Two of the most important of all — Boardman and Danforth — lived in Hartford, Connecticut. The name Boardman is one that appears frequently on pewter and may give rise to some confusion. In the first place, there was a well-known pewterer named Thomas Boardman, who was at work in London about the middle of the eighteenth century. His work, however, being of an earlier period, can easily be distinguished from that of the American Boardmans. He also used a different touch, with the name Boardman or Thomas Board man. In the second place, there was more than one Boardman concern in this country. In the New York Directory of 1824 the name appears as Timothy Boardman & Co., at 173 water Street. In the 1828 directory, Boardman & Hart are found at 178 Water Street — probably the same Boardman. In 1832 they appear to have moved to Burling Slip, where they made britannia ware until 1841. Some of their ware was marked with the firm name. The most famous pewterer of the name, however, was Thomas D. Boardman of Hartford, who did his best work about 1825. Only his earlier ware is worth consideration, for much of his metal is of inferior quality and he soon went into the britannia business. On his larger ware his mark was an eagle with Thomas D. above and Boardman below. On his smaller ware he used a different eagle, with T. D. B. below. The word Hartford in a plain rectangle generally appears as a separate mark. Samuel Danforth, also of Hartford, worked some what earlier in the nineteenth century. His touch was a spread eagle with Samuel above and Danforth below, accompanied by the word Hartford in a separate rectangle. He also frequently used hall-marks consisting of his initials, a spread eagle, and an eight- pointed star, arranged in a row. The Gallatin Reformed Church of Mount Ross, New York, owns two beakers, a plate, and a flagon by Boardman, as well as a plate by Henry Will (New York, 1765-86). Two Danforth beakers are owned by the First Presbyterian Church of Orange, New Jersey. Though the names of Boardman and Danforth are as well known as any, their work should not be ranked high either in respect to age or quality. In fact, some of our finest pewter is by unknown makers. The earliest American pewterers on record were the following, all in Boston: Thomas Bumsteed, 1654; Thomas Clarke, 1683; John Comer, 1678; Henry Shrimpton, 1660-5; and Richard Graves, 1639, who appears to have worked also in Salem. The dates indicate the earliest mention of their names. In the Revolutionary period Thomas Badger was a pewterer of some prominence. He had a shop on Prince Street, and his name appears in the Boston directories from 1789 to 1810. His touch was round at the top and square at the bottom, with Thomas above a spread eagle and Badger below. He also used the separate stamp, Boston. It

has been stated that Paul Revere added pewter-making to his many

other accomplishments, but I have discovered no evidence of it.

Early in the nineteenth century Mary Jackson, at the Sign of the Tankard, Cornhill, had one of the largest pewtering establishments in Boston. It was famous for its porringers. Not much more is known about the New York pewterers than about those of Boston. In 1743, John Halden advertised pewter ware made and sold at his shop at Market Slip. In 1744, James Leddel was selling pewter at the Sign of the Platter, in Dock Street; at the end of that year he moved to the foot of wall Street. In 1745 we find Robert Boyle dealing in pewter ware at the Sign of the Gilt Dish in Dock Street. It is doubtful, however, if Leddel or Boyle manufactured extensively. The only pewterers mentioned by trade in New York's first City Directory in 1786 were Francis Basset, 218 Queen Street, William Kirkby, 23 Dock Street, and Henry Will, 3 Water Street. In 1794 we find the trades of plumber and pewterer combined in an advertisement of Malcolm McEwen & Son, Water Street and Beekman Slip. Philadelphia's earliest known pewterers were James Everett and Simon Edgell, first mentioned about 1718. There was also a Cornelius Bradford before the Revolution, but most of the names belong to the later period. Charlotte Hero, widow, 230 North Second Street, and William Will, 66 North Second Street, are given as pewterers in the Philadelphia Directory of 1796. The names of C. & I. Hera — probably the same as Hero — appear again in the Philadelphia Directory of 1810. Three plates made by this firm are owned by the Princeton Theological Seminary, together with Other old American pewter. Providence supported several pewterers of distinction, notably William Calder, of 166 North Main Street, and Samuel E. Hamlin, 109 North Main Street. Both are mentioned in the Providence Directory of 1824, though Hamlin at least was at work several years before that. At about the same time G. Richardson was a pewterer at Cranston, R. I. All three used the eagle in their touches. Pewter was also made in Baltimore, Cincinnati, and else where, but no records have been gathered of the pewterers. Though pewter was very common during the eighteenth century there is less of it to be found to day than might be supposed. Quantities of it were melted up in the stern days of '76 and were turned into Revolutionary bullets, and much of the later ware found its way to the junk heap when pewter went out of fashion. American pewter, therefore, is well worth collecting, particularly the earlier ware. of course, some discrimination should be exercised, as not all of it was good in form or finish. When obtainable, American pewter is not excessively valuable to-day. The hollow ware is worth rather more than the flatware. Tankards are worth from $8 or $9 apiece to $15 or $18, according to age and style. Teapots are worth from $10 to $20 if genuine pewter; the later alloys have little value. Sugar bowls and porringers are worth $ 4 or $5, pepper shakers $2 or $3, plain bowls about $2, and spoons $1 or $2 for the ordinary types. The smaller plates may often be bought for $1 each, and are seldom worth over $3 or $4. Medium-sized plates and trenchers are worth from $3 to $6, and the largest plates and platters from $6 to $10. In spite of these comparatively low prices, pewter has been faked to a considerable extent. Pewter- making is not a lost art, and counterfeiters have discovered how to make it look old. Some of it has even been made from the original molds, and the counterfeit is not at all easy to detect. Within the past ten or fifteen years there has been a considerable traffic in bogus jugs, flagons, porringers, plates, pep per shakers, spoons, and whale-oil lamps. while it is frequently possible for the expert to detect the fraud, the average collector will do well to verify the individual history of the piece he purchases.

COPPERSMITHS

AND BRASIERS

Of

the early American coppersmiths and brasiers even less is known than

of the pewterers, though there were doubtless several of them among

our early immigrants. During the first half of the eighteenth century

a number of them came from England and settled in various parts of

the country, and there were evidently Dutch and German brasiers in

New York and Pennsylvania. They employed largely the forms in vogue

in the old countries, so that their work is not readily distinguished

from the imported ware. By the middle of the century we were making a

large part of the brass and copper ware used here.

Among the brass articles that were made in this country were tea-kettles, jugs, sugar bowls, milk cans, pitchers, big round kettles, pipkins or coal scuttles, fenders, andirons and fire sets, braziers, whale- oil and camphine lamps, candlesticks, door knockers, snuffers and candle trays, tobacco boxes, thimbles, drawer pulls, handles and scutcheons, hinges, locks, eagle ornaments for Revolutionary accoutrements, and buttons. About 1780 the character of the brass ware changed somewhat owing to the introduction of a new method of casting the copper and zinc together. Much of the old brass and copper ware was made by obscure local craftsmen whose names have not been preserved. One of the earliest brasiers on record here was Henry Shrimpton of Boston, who died in 1665. Another famous New England brasier was Jonathan Jackson, who died in 1736. He made brass pots, kettles, skillets, hand basins, plates, saucers, spoons, knockers, candlesticks, stirrups, spurs, staples, fire-dogs or andirons, and warming- pans. At his death he left a fortune of over £8,000. His widow, Mary Jackson, and his son William continued the business at the Brazier's Head, Cornhill, Boston, though they may not have manufactured anything. Edward Jackson, another member of the family, was also a brasier. In New York we find this advertisement dated 1743: "John Halden, brasier, from London, near the old Market Slip in New York, makes and sells all sorts of copper and brass kettles, tea-kettles, coffee potts, pye pans, warming pans, and all sorts of copper and brass ware, also sells all sorts of hard metal and pewter wares." The 1786 New York Directory gives the names of James Kip, 59 Broadway, and Abram Montayne, 13 King Street, brass founders. In 1802 a brass foundry called Probes' Furnace was set up in West Liberty, Pennsylvania, by an Alsatian who made many kinds of brass and copper vessels. Such are the meager accounts that have come down to us of the brasiers. Most of them were also coppersmiths. of those who worked in copper, Paul Revere & Son were the most notable examples. Though many of our copper utensils were imported, it is probable that local coppersmiths made tea kettles, warming-pans, ladles, kettles, basins, candle-sticks, measures, cans, and pots. American copper hot-water urns are very rare. Copper chafing-dishes and braziers, with tea-kettle and charcoal pan, were made by the Reveres. They were usually called copper furnaces. A very fine one, of hand some design, is owned by the Concord Antiquarian Society. While

every collector appreciates the beauty of old brass and copper, it is

rather difficult to attempt making a specialty of American ware. The

same is true of Sheffield plate, which was probably not made in this

country at all until after 1800. Eighteenth century pewter cider jug and whale-oil lamp. Bolles Collection |