| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2022

(Return

to Web

Text-ures)

| Click

Here to return to Etruscan Places Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

TARQUINIA In Cerveteri there is

nowhere to sleep, so the only thing to do is to go back to Rome, or forwards to

Cività Vecchia. The bus landed us at the station of Palo at about five o'clock:

in the midst of nowhere: to meet the Rome train. But we were going on to

Tarquinia, not back to Rome, so we must wait two hours, till seven. In the distance we

could see the concrete villas and new houses of what was evidently Ladispoli, a

seaside place, some two miles away. So we set off to walk to Ladispoli, on the

flat sea-road. On the left, in the wood that forms part of the great park, the

nightingales had already begun to whistle, and looking over the wall one could

see many little rose-coloured cyclamens glowing on the earth in the evening

light. We walked on, and the

Rome train came surging round the bend. It misses Ladispoli, whose two miles of

branch line runs only in the hot bathing months. As we neared the first ugly

villas on the road the ancient wagonette drawn by the ancient white horse, both

looking sun-bitten almost to ghostliness, clattered past. It just beat us. Ladispoli is one of

those ugly little places on the Roman coast, consisting of new concrete villas,

new concrete hotels, kiosks and bathing establishments; bareness and

nonexistence for ten months in the year, seething solid with fleshy bathers in

July and August. Now it was deserted, quite deserted, save for two or three

officials and four wild children. B. and I lay on the

grey-black lava sand, by the flat, low sea, over which the sky, grey and

shapeless, emitted a flat, wan evening light. Little waves curled green out of

the sea's dark greyness, from the curious low flatness of the water. It is a

peculiarly forlorn coast, the sea peculiarly flat and sunken, lifeless-looking,

the land as if it had given its last gasp, and was now for ever inert. Yet this is the

Tyrrhenian sea of the Etruscans, where their shipping spread sharp sails, and

beat the sea with slave-oars, roving in from Greece and Sicily, Sicily of the

Greek tyrants; from Cumae, the city of the old Greek colony of Campania, where

the province of Naples now is; and from Elba, where the Etruscans mined their

iron ore. The Etruscans sailed the seas. They are even said to have come by

sea, from Lydia in Asia Minor, at some date far back in the dim mists before

the eighth century B.C. But that a whole people, even a whole host, sailed in

the tiny ships of those days, all at once, to people a sparsely peopled central

Italy, seems hard to imagine. Probably ships did come — even before Ulysses.

Probably men landed on the strange flat coast, and made camps, and then treated

with the natives. Whether the newcomers were Lydians or Hittites with hair

curled in a roll behind, or men from Mycenae or Crete, who knows. Perhaps men

of all these sorts came, in batches. For in Homeric days a restlessness seems

to have possessed the Mediterranean basin, and ancient races began shaking

ships like seeds over the sea. More people than Greeks, or Hellenes, or

Indo-Germanic groups, were on the move. But whatever little

ships were run ashore on the soft, deep, grey-black volcanic sand of this

coast, three thousand years ago, and earlier, their mariners certainly did not

find those hills inland empty of people. If the Lydians or Hittites pulled up

their long little two-eyed ships on to the beach, and made a camp behind a

bank, in shelter from the wet strong wind, what natives came down curiously to

look at them? For natives there were, of that we may be certain. Even before

the fall of Troy, before even Athens was dreamed of, there were natives here.

And they had huts on the hills, thatched huts in clumsy groups most probably;

with patches of grain, and flocks of goats and probably cattle. Probably it was

like coming on an old Irish village, or a village in the Scottish Hebrides in

Prince Charlie's day, to come upon a village of these Italian aborigines, by

the Tyrrhenian sea, three thousand years ago. But by the time Etruscan history

starts in Caere, some eight centuries B.C., there was certainly more than a

village on the hill. There was a native city, of that we may be sure; and a

busy spinning of linen and beating of gold, long before the Regolini-Galassi

tomb was built. However that may be,

somebody carne, and somebody was already here: of that we may be certain: and,

in the first place, none of them were Greeks or Hellenes. It was the days

before Rome rose up: probably when the first corners arrived it was the days

even before Homer. The newcomers, whether they were few or many, seem to have

come from the east, Asia Minor or Crete or Cyprus. They were, we must feel, of

an old, primitive Mediterranean and Asiatic or Aegean stock. The twilight of

the beginning of our history was the nightfall of some previous history, which

will never be written. Pelasgian is but a shadow-word: But Hittite and Minoan,

Lydian, Carian, Etruscan, these words emerge from shadow, and perhaps from one

and the same great shadow come the peoples to whom the names belong. The Etruscan

civilization seems a shoot, perhaps the last, from the prehistoric

Mediterranean world, and the Etruscans, newcomers and aborigines alike,

probably belonged to that ancient world, though they were of different nations

and levels of culture. Later, of course, the Greeks exerted a great influence.

But that is another matter. Whatever happened, the

newcomers in ancient central Italy found many natives flourishing in possession

of the land. These aboriginals, now ridiculously called Villanovans, were

neither wiped out nor suppressed. Probably they welcomed the strangers, whose

pulse was not hostile to their own. Probably the more highly developed religion

of the newcomers was not hostile to the primitive religion of the aborigines:

no doubt the two religions had the same root. Probably the aborigines formed

willingly a sort of religious aristocracy from the newcomers: the Italians

might almost do the same today. And so the Etruscan world arose. But it took

centuries to arise. Etruria was not a colony, it was a slowly developed

country. There was never an

Etruscan nation: only, in historical times, a great league of tribes or nations

using the Etruscan language and the Etruscan script — at least officially — and

uniting in their religious feeling and observances. The Etruscan alphabet seems

to have been borrowed from the old Greeks, apparently from the Chalcidians of

Cumae — the Greek colony just north of where Naples now is. But the Etruscan

language is not akin to any of the Greek dialects, nor, apparently, to the

Italic. But we don't know. It is probably to a great extent the language of the

old aboriginals of southern Etruria, just as the religion is in all probability

basically aboriginal, belonging to some vast old religion of the prehistoric

world. From the shadow of the prehistoric world emerge dying religions that

have not yet invented gods or goddesses, but live by the mystery of the

elemental powers in the Universe, the complex vitalities of what we feebly call

Nature. And the Etruscan religion was certainly one of these. The gods and

goddesses don't seem to have emerged in any sharp definiteness. But it is not for me to

make assertions. Only, that which half emerges from the dim background of time

is strangely stirring; and after having read all the learned suggestions, most

of them contradicting one another; and then having looked sensitively at the

tombs and the Etruscan things that are left, one must accept one's own

resultant feeling. Ships came along this

low, inconspicuous sea, coming up from the Near East, we should imagine, even

in the days of Solomon — even, maybe, in the days of Abraham. And they kept on

coming. As the light of history dawns and brightens, we see them winging along

with their white or scarlet sails. Then, as the Greeks came crowding into

colonies in Italy, and the Phoenicians began to exploit the western

Mediterranean, we begin to hear of the silent Etruscans, and to see them. Just north of here

Caere founded a port called Pyrgi, and we know that the Greek vessels flocked

in, with vases and stuffs and colonists coming from Hellas or from Magna

Graecia, and that Phoenician ships came rowing sharply, over from Sardinia, up

from Carthage, round from Tyre and Sidon; while the Etruscans had their own

fleets, built of timber from the mountains, caulked with pitch from northern

Volterra, fitted with sails from Tarquinia, filled with wheat from the

bountiful plains, or with the famous Etruscan articles of bronze and iron,

which they carried away to Corinth or to Athens or to the ports of Asia Minor.

We know of the great and finally disastrous sea-battles with the Phoenicians

and the tyrant of Syracuse. And we know that the Etruscans, all except those of

Caere, became ruthless pirates, almost like the Moors and the Barbary corsairs

later on. This was part of their viciousness, a great annoyance to their loving

and harmless neighbours, the law-abiding Romans — who believed in the supreme

law of conquest. However, all this is

long ago. The very coast has changed since then. The smitten sea has sunk and

fallen back, the weary land has emerged when, apparently, it didn't want to,

and the flowers of the coast-line are miserable bathing-places such as Ladispoli

and seaside Ostia, desecration put upon desolation, to the triumphant trump of

the mosquito. The wind blew flat and

almost chill from the darkening sea, the dead waves lifted small bits of pure

green out of the leaden greyness, under the leaden sky. We got up from the dark

grey but soft sand, and went back along the road to the station, peered at by

the few people and officials who were holding the place together till the next

bathers carne. At the station there

was general desertedness. But our things still lay untouched in a dark corner

of the buffet, and the man gave us a decent little meal of cold meats and wine

and oranges. It was already night. The train came rushing in, punctually. It is an hour or more

to Cività Vecchia, which is a port of not much importance, except that from

here the regular steamer sails to Sardinia. We gave our things to a friendly

old porter, and told him to take us to the nearest hotel. It was night, very

dark as we emerged from the station. And a fellow came

furtively shouldering up to me. 'You are foreigners,

aren't you?' 'Yes.' 'What nationality?' 'English.' 'You have your

permission to reside in Italy — or your passport?' 'My passport I have — what

do you want?' 'I want to look at your

passport.' 'It's in the valise!

And why? Why is this?' 'This is a port, and we

must examine the papers of foreigners. 'And why? Genoa is a

port, and no one dreams of asking for papers.' I was furious. He made

no answer. I told the porter to go on to the hotel, and the fellow furtively

followed at our side, half-a-pace to the rear, in the mongrel way these

spy-louts have. In the hotel I asked

for a room and registered, and then the fellow asked again for my passport. I

wanted to know why he demanded it, what he meant by accosting me outside the

station as if I was a criminal, what he meant by insulting us with his

requests, when in any other town in Italy one went unquestioned — and so forth,

in considerable rage. He did not reply, but

obstinately looked as though he would be venomous if he could. He peered at the

passport — though I doubt if he could make head or tail of it — asked where we

were going, peered at B.'s passport, half excused himself in a whining,

disgusting sort of fashion, and disappeared into the night. A real lout. I was furious.

Supposing I had not been carrying my passport — and usually I don't dream of

carrying it — what amount of trouble would that lout have made me! Probably I

should have spent the night in prison, and been bullied by half a dozen low

bullies. Those poor rats at

Ladispoli had seen me and B. go to the sea and sit on the sand for

half-an-hour, then go back to the train. And this was enough to rouse their

suspicions, I imagine, so they telegraphed to Cività Vecchia. Why are officials

always fools? Even when there is no war on? What could they imagine we were

doing? The hotel manager,

propitious, said there was a very interesting museum in Cività Vecchia, and

wouldn't we stay the next day and see it. 'Ah!' I replied. 'But all it contains

is Roman stuff, and we don't want to look at that.' It was malice on my part,

because the present regime considers itself purely ancient Roman. The man

looked at me scared, and I grinned at him. 'But what do they mean,' I said,

'behaving like this to a simple traveller, in a country where foreigners are

invited to travel!' 'Ah!' said the porter softly and soothingly. 'It is the

Roman province. You will have no more of it when you leave the Provincia di

Roma.' And when the Italians give the soft answer to turn away wrath, the wrath

somehow turns away. We walked for an hour

in the dull street of Cività Vecchia. There seemed so much suspicion, one would

have thought there were several wars on. The hotel manager asked if we were

staying. We said we were leaving by the eight-o'clock train in the morning, for

Tarquinia. And, sure enough, we

left by the eight-o'clock train. Tarquinia is only one station from Cività

Vecchia — about twenty minutes over the fiat Maremma country, with the sea on

the left, and the green wheat growing luxuriantly, the asphodel sticking up its

spikes. We soon saw Tarquinia,

its towers pricking up like antennae on the side of a low bluff of a hill, some

few miles inland from the sea. And this was once the metropolis of Etruria,

chief city of the great Etruscan League. But it died like all the other

Etruscan cities, and had a more or less medieval rebirth, with a new name.

Dante knew it, as it was known for centuries, as Corneto — Corgnetum or

Cornetium — and forgotten was its Etruscan past. Then there was a feeble sort

of wakening to remembrance a hundred years ago, and the town got Tarquinia

tacked on to its Corneto: Corneto-Tarquinia. The Fascist regime, however,

glorying in the Italian origins of Italy, has now struck out the Corneto, so

the town is once more, simply, Tarquinia. As you come up in the motor-bus from

the station you see the great black letters, on a white ground, painted on the

wall by the city gateway: Tarquinia. So the wheel of revolution turns.

There stands the Etruscan word — Latinized Etruscan — beside the medieval gate,

put up by the Fascist power to name and unname. But the Fascists, who

consider themselves in all things Roman, Roman of the Caesars, heirs of Empire

and world power, are beside the mark restoring the rags of dignity to Etruscan

places. For of all the Italian people that ever lived, the Etruscans were

surely the least Roman. Just as, of all the people that ever rose up in Italy,

the Romans of ancient Rome were surely the most un-Italian, judging from the

natives of today. Tarquinia is only about

three miles from the sea. The omnibus soon runs one up, charges through the

widened gateway, swirls round in the empty space inside the gateway, and is

finished. We descend in the bare place, which seems to expect nothing. On the

left is a beautiful stone palazzo — on the right is a café, upon the low

ramparts above the gate. The man of the Dazio, the town customs, looks to see

if anybody has brought food-stuffs into the town — but it is a mere glance. I

ask him for the hotel. He says: 'Do you mean to sleep?' I say I do. Then he

tells a small boy to carry my bag and takes us to Gentile's. Nowhere is far off, in

these small wall-girdled cities. In the warm April morning the stony little

town seems half asleep. As a matter of fact, most of the inhabitants are out in

the fields, and won't come in through the gates again till evening. The slight

sense of desertedness is everywhere — even in the inn, when we have climbed up

the stairs to it, for the ground floor does not belong. A little lad in long

trousers, who would seem to be only twelve years old but who has the air of a

mature man, confronts us with his chest out. We ask for rooms. He eyes us,

darts away for the key, and leads us off upstairs another flight, shouting to a

young girl, who acts as chambermaid, to follow on. He shows us two small rooms,

opening off a big, desert sort of general assembly room common in this kind of

inn. 'And you won't be lonely,' he said briskly, 'because you can talk to one

another through the wall. Toh! Lina!' He lifts his finger and listens.

'Eh!' comes through the wall, like an echo, with startling nearness and

clearness. 'Fai presto!' says Albertino. 'E pronto!' comes the

voice of Lina. 'Ecco!' says Albertino to us. 'You hear!' We certainly did.

The partition wall must have been butter-muslin. And Albertino was delighted,

having reassured us we should not feel lonely nor frightened in the night. He was, in fact, the

most manly and fatherly little hotel manager I have ever known, and he ran the

whole place. He was in reality fourteen years old, but stunted. From five in

the morning till ten at night he was on the go, never ceasing, and with a

queer, abrupt, sideways-darting alacrity that must have wasted a great deal of

energy. The father and mother were in the background — quite young and

pleasant. But they didn't seem to exert themselves. Albertino did it all. How

Dickens would have loved him! But Dickens would not have seen the queer

wistfulness, and trustfulness, and courage in the boy. He was absolutely

unsuspicious of us strangers. People must be rather human and decent in

Tarquinia, even the commercial travellers: who, presumably, are chiefly buyers

of agricultural produce, and sellers of agricultural implements and so forth. We sallied out, back to

the space by the gate, and drank coffee at one of the tin tables outside.

Beyond the wall there were a few new villas — the land dropped green and quick,

to the strip of coast plain and the indistinct, faintly gleaming sea, which

seemed somehow not like a sea at all. I was thinking, if this

were still an Etruscan city, there would still be this cleared space just

inside the gate. But instead of a rather forlorn vacant lot it would be a

sacred clearing, with a little temple to keep it alert. Myself, I like to think

of the little wooden temples of the early Greeks and of the Etruscans: small,

dainty, fragile, and evanescent as flowers. We have reached the stage when we

are weary of huge stone erections, and we begin to realize that it is better to

keep life fluid and changing than to try to hold it fast down in heavy

monuments. Burdens on the face of the earth are man's ponderous erections. The Etruscans made

small temples, like little houses with pointed roofs, entirely of wood. But

then, outside, they had friezes and cornices and crests of terra-cotta, so that

the upper part of the temple would seem almost made of earthenware, terra-cotta

plaques fitted neatly, and alive with freely modelled painted figures in

relief, gay dancing creatures, rows of ducks, round faces like the sun, and

faces grinning and putting out a big tongue, all vivid and fresh and

unimposing. The whole thing small and dainty in proportion, and fresh, somehow

charming instead of impressive. There seems to have been in the Etruscan

instinct a real desire to preserve the natural humour of life. And that is a

task surely more worthy, and even much more difficult in the long run, than

conquering the world or sacrificing the self or saving the immortal soul. Why has mankind had

such a craving to be imposed upon? Why this lust after imposing creeds,

imposing deeds, imposing buildings, imposing language, imposing works of art?

The thing becomes an imposition and a weariness at last. Give us things that

are alive and flexible, which won't last too long and become an obstruction and

a weariness. Even Michelangelo becomes at last a lump and a burden and a bore.

It is so hard to see past him. Across the space from

the café is the Palazzo Vitelleschi, a charming building, now a national museum

— so the marble slab says. But the heavy doors are shut. The place opens at

ten, a man says. It is nine-thirty. We wander up the steep but not very long

street, to the top. And the top is a

fragment of public garden, and a look-out. Two old men are sitting in the sun,

under a tree. We walk to the parapet, and suddenly are looking into one of the

most delightful landscapes I have ever seen: as it were, into the very

virginity of hilly green country. It is all wheat — green and soft and

swooping, swooping down and up, and glowing with green newness, and no houses.

Down goes the declivity below us, then swerving the curve and up again, to the

neighbouring hill that faces in all its greenness and long-running

immaculateness. Beyond, the hills ripple away to the mountains, and far in the

distance stands a round peak, that seems to have an enchanted city on its

summit. Such a pure, uprising,

unsullied country, in the greenness of wheat on an April morning! — and the

queer complication of hills! There seems nothing of the modern world here — no

houses, no contrivances, only a sort of fair wonder and stillness, an openness

which has not been violated. The hill opposite is

like a distinct companion. The near end is quite steep and wild, with evergreen

oaks and scrub, and specks of black-and-white cattle on the slopes of common.

But the long crest is green again with wheat, running and drooping to the

south. And immediately one feels: that hill has a soul, it has a meaning. Lying thus opposite to

Tarquinia's long hill, a companion across a suave little swing of valley, one

feels at once that, if this is the hill where the living Tarquinians had their

gay wooden houses, then that is the hill where the dead lie buried and quick,

as seeds, in their painted houses underground. The two hills are as inseparable

as life and death, even now, on the sunny, green-filled April morning with the

breeze blowing in from the sea. And the land beyond seems as mysterious and

fresh as if it were still the morning of Time. But B. wants to go back

to the Palazzo Vitelleschi: it will be open now. Down the street we go, and

sure enough the big doors are open, several officials are in the shadowy

courtyard entrance. They salute us in the Fascist manner; alla romana! Why

don't they discover the Etruscan salute, and salute us all'etrusca! But

they are perfectly courteous and friendly. We go into the courtyard of the

palace. The museum is

exceedingly interesting and delightful, to anyone who is even a bit aware of

the Etruscans. It contains a great number of things found at Tarquinia, and

important things. If only we would

realize it, and not tear things from their settings. Museums anyhow are wrong.

But if one must have museums, let them be small, and above all, let them be

local. Splendid as the Etruscan museum is in Florence, how much happier one is

in the museum at Tarquinia, where all the things are Tarquinian, and at least

have some association with one another, and form some sort of organic

whole. In an entrance room

from the cortile lie a few of the long sarcophagi in which the nobles were

buried. It seems as if the primitive inhabitants of this part of Italy always

burned their dead, and then put the ashes in a jar, sometimes covering the jar

with the dead man's helmet, sometimes with a shallow dish for a lid, and then

laid the urn with its ashes in a little round grave like a little well. This is

called the Villanovan way of burial, in the well-tomb. The newcomers to the

country, however, apparently buried their dead whole. Here, at Tarquinia, you

may still see the hills where the well-tombs of the aboriginal inhabitants are

discovered, with the urns containing the ashes inside. Then come the graves

where the dead were buried unburned, graves very much like those of today. But

tombs of the same period with cinerary urns are found near to, or in connexion.

So that the new people and the old apparently lived side by side in harmony,

from very early days, and the two modes of burial continued side by side, for

centuries, long before the painted tombs were made. At Tarquinia, however,

the main practice seems to have been, at least from the seventh century on,

that the nobles were buried in the great sarcophagi, or laid out on biers, and

placed in chamber-tombs, while the slaves apparently were cremated, their ashes

laid in urns, and the urns often placed in the family tomb, where the stone

coffins of the masters rested. The common people, on the other hand, were

apparently sometimes cremated, sometimes buried in graves very much like our

graves of today, though the sides were lined with stone. The mass of the common

people was mixed in race, and the bulk of them were probably serf-peasants,

with many half-free artisans. These must have followed their own desire in the

matter of burial: some had graves, many must have been cremated, their ashes

saved in an urn or jar which takes up little room in a poor man's burial-place.

Probably even the less important members of the noble families were cremated,

and their remains placed in the vases, which became more beautiful as the

connexion with Greece grew more extensive. It is a relief to think

that even the slaves — and the luxurious Etruscans had many, in historical

times — had their remains decently stored in jars and laid in a sacred place.

Apparently the 'vicious Etruscans' had nothing comparable to the vast dead-pits

which lay outside Rome, beside the great highway, in which the bodies of slaves

were promiscuously flung. It is all a question of

sensitiveness. Brute force and overbearing may make a terrific effect. But in

the end, that which lives lives by delicate sensitiveness. If it were a

question of brute force, not a single human baby would survive for a fortnight.

It is the grass of the field, most frail of all things, that supports all life

all the time. But for the green grass, no empire would rise, no man would eat

bread: for grain is grass; and Hercules or Napoleon or Henry Ford would alike

be denied existence. Brute force crushes

many plants. Yet the plants rise again. The Pyramids will not last a moment

compared with the daisy. And before Buddha or Jesus spoke the nightingale sang,

and long after the words of Jesus and Buddha are gone into oblivion the

nightingale still will sing. Because it is neither preaching nor teaching nor

commanding nor urging. It is just singing. And in the beginning was not a Word,

but a chirrup. Because a fool kills a

nightingale with a stone, is he therefore greater than the nightingale? Because

the Roman took the life out of the Etruscan, was he therefore greater than the Etruscan?

Not he! Rome fell, and the Roman phenomenon with it. Italy today is far more

Etruscan in its pulse than Roman; and will always be so. The Etruscan element

is like the grass of the field and the sprouting of corn, in Italy: it will

always be so. Why try to revert to the Latin-Roman mechanism and suppression? In the open room upon

the courtyard of the Palazzo Vitelleschi lie a few sarcophagi of stone, with

the effigies carved on top, something as the dead crusaders in English

churches. And here, in Tarquinia, the effigies are more like crusaders than

usual, for some lie flat on their backs, and have a dog at their feet; whereas

usually the carved figure of the dead rears up as if alive, from the lid of the

tomb, resting upon one elbow, and gazing out proudly, sternly. If it is a man,

his body is exposed to just below the navel, and he holds in his hand the

sacred patera, or mundum, the round saucer with the raised knob

in the centre, which represents the round germ of heaven and earth. It stands

for the plasm, also, of the living cell, with its nucleus, which is the

indivisible God of the beginning, and which remains alive and unbroken to the

end, the eternal quick of all things, which yet divides and sub-divides, so

that it becomes the sun of the firmament and the lotus of the waters under the

earth, and the rose of all existence upon the earth: and the sun maintains its

own quick, unbroken for ever; and there is a living quick of the sea, and of

all the waters; and every living created thing has its own unfailing quick. So

within each man is the quick of him, when he is a baby, and when he is old, the

same quick; some spark, some unborn and undying vivid life-electron. And this

is what this symbolized in the patera, which may be made to flower like

a rose or like the sun, but which remains the same, the germ central within the

living plasm. And this patera,

this symbol, is almost invariably found in the hand of a dead man. But if the

dead is a woman her dress falls in soft gathers from her throat, she wears

splendid jewellery, and she holds in her hand not the mundum, but the mirror,

the box of essence, the pomegranate, some symbols of her reflected nature, or

of her woman's quality. But she, too, is given a proud, haughty look, as is the

man: for she belongs to the sacred families that rule and that read the signs. These sarcophagi and

effigies here all belong to the centuries of the Etruscan decline, after there

had been long intercourse with the Greeks, and perhaps most of them were made

after the conquest of Etruria by the Romans. So that we do not look for fresh,

spontaneous works of art, any more than we do in modern memorial stones. The

funerary arts are always more or less commercial. The rich man orders his

sarcophagus while he is still alive, and the monument-carver makes the work

more or less elaborate, according to the price. The figure is supposed to be a

portrait of the man who orders it, so we see well enough what the later

Etruscans look like. In the third and second centuries B.C., at the fag end of

their existence as a people, they look very like the Romans of the same day,

whose busts we know so well. And often they are given the tiresomely haughty

air of people who are no longer rulers indeed, only by virtue of wealth. Yet, even when the Etruscan

art is Romanized and spoilt; there still flickers in it a certain naturalness

and feeling. The Etruscan Lucumones, or prince-magistrates, were in the first

place religious seers, governors in religion, then magistrates, then princes.

They were not aristocrats in the Germanic sense, not even patricians in the

Roman. They were first and foremost leaders in the sacred mysteries, then

magistrates, then men of family and wealth. So there is always a touch of vital

life, of life-significance. And you may look through modern funerary sculpture

in vain for anything so good even as the Sarcophagus of the Magistrate, with

his written scroll spread before him, his strong, alert old face gazing sternly

out, the necklace of office round his neck, the ring of rank on his finger. So

he lies, in the museum at Tarquinia. His robe leaves him naked to the hip, and

his body lies soft and slack, with the soft effect of relaxed flesh the

Etruscan artists render so well, and which is so difficult. On the sculptured

side of the sarcophagus the two death-dealers wield the hammer of death, the

winged figures wait for the soul, and will not be persuaded away. Beautiful it

is, with the easy simplicity of life. But it is late in date. Probably this old

Etruscan magistrate is already an official under Roman authority: for he does

not hold the sacred mundum, the dish, he has only the written scroll,

probably of laws. As if he were no longer the religious lord or Lucumo. Though

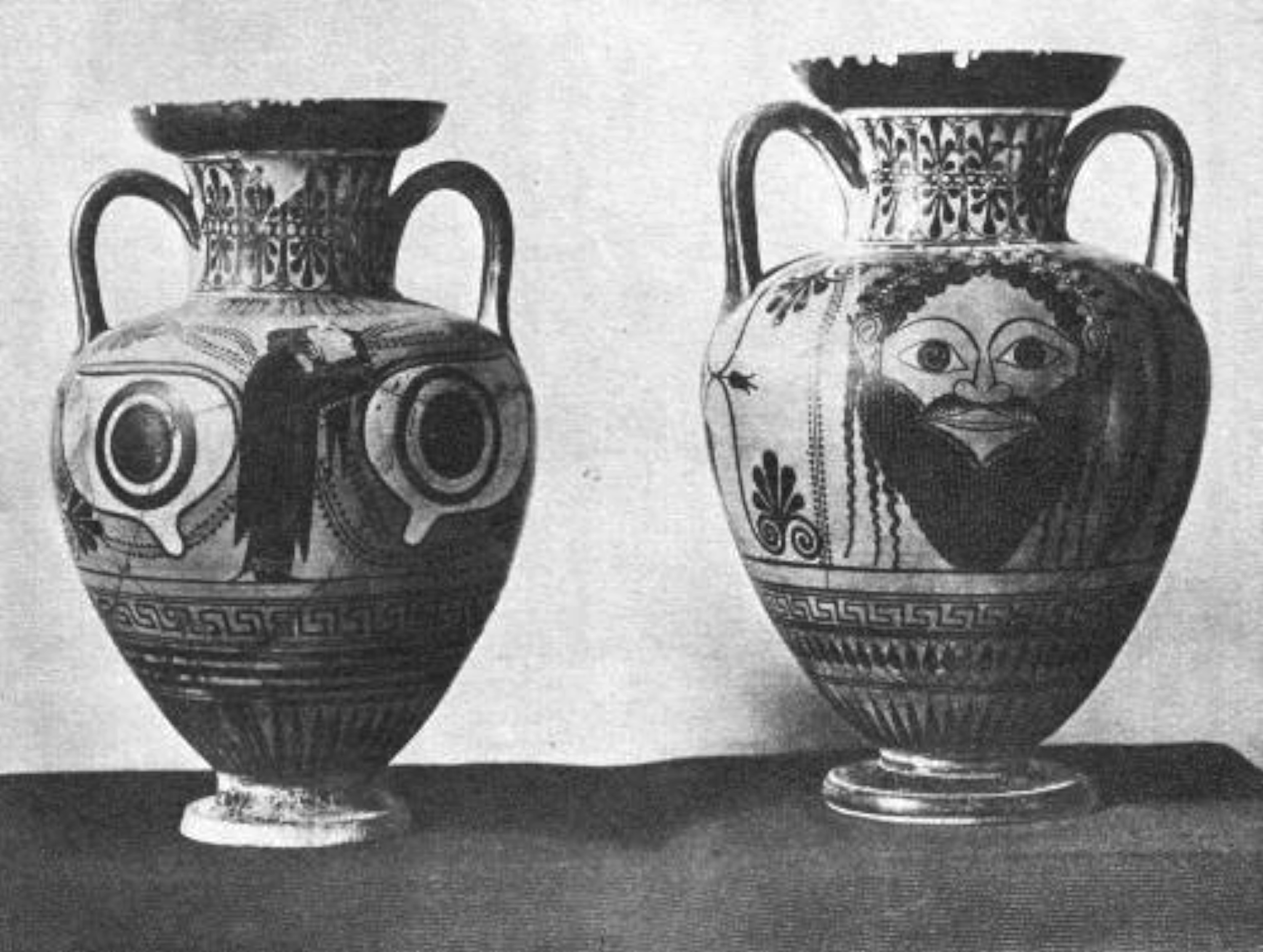

possibly, in this case, the dead man was not one of the Lucumones anyhow. Upstairs in the museum

are many vases, from the ancient crude pottery of the Villanovans to the early

black ware decorated in scratches, or undecorated, called bucchero, and

on to the painted bowls and dishes and amphoras which came from Corinth or

Athens, or to those painted pots made by the Etruscans themselves more or less

after the Greek patterns. These may or may not be interesting: the Etruscans

are not at their best, painting dishes. Yet they must have loved them, in the

early days these great jars and bowls, and smaller mixing bowls, and drinking

cups and pitchers, and flat winecups formed a valuable part of the household

treasure. In very early times the Etruscans must have sailed their ships to

Corinth and to Athens, taking perhaps wheat and honey, wax and bronze-ware,

iron and gold, and coming back with these precious jars, and stuffs, essences,

perfumes, and spice. And jars brought from overseas for the sake of their

painted beauty must have been household treasures. But then the Etruscans

made pottery of their own, and by the thousand they imitated the Greek vases.

So that there must have been millions of beautiful jars in Etruria. Already in

the first century B.C. there was a passion among the Romans for collecting

Greek and Etruscan painted jars from the Etruscans, particularly from the

Etruscan tombs: jars and the little bronze votive figures and statuettes, the

sigilla Tyrrhena of the Roman luxury. And when the tombs were first robbed,

for gold and silver treasure, hundreds of fine jars must have been thrown over

and smashed. Because even now, when a part-rifled tomb is discovered and

opened, the fragments of smashed vases lie around. As it is, however, the

museums are full of vases. If one looks for the Greek form of elegance and

convention, those elegant still-unravished ‘brides of quietness', one is

disappointed. But get over the strange desire we have for elegant convention,

and the vases and dishes of the Etruscans, especially many of the black

bucchero ware, begin to open out like strange flowers, black flowers with all

the softness and the rebellion of life against convention, or red-and-black

flowers painted with amusing free, bold designs. It is there nearly always in

Etruscan things, the naturalness verging on the commonplace, but usually

missing it, and often achieving an originality so free and bold, and so fresh,

that we who love convention and things 'reduced to a norm', call it a bastard

art; and commonplace. It is useless to look

in Etruscan things for 'uplift'. If you want uplift, go to the Greek and the

Gothic. If you want mass, go to the Roman. But if you love the odd spontaneous

forms that are never to be standardized, go to the Etruscans. In the

fascinating little Palazzo Vitelleschi one could spend many an hour, but for

the fact that the very fullness of museums makes one rush through them.

|