| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

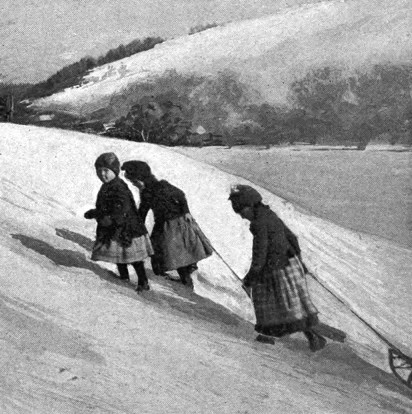

THE

FARMER'S BOY.

PART I. WINTER. ON New-Years morning the first thing the boy hears is the voice of his father calling from the foot of the stairs, "Come, Frank — time to get up!" You may perhaps imagine that the boy leaps lightly from his bed, and that he is soon clattering merrily down the stairs to the tune of his own whistle. But the real, live boy who will fit so romantic and pretty an impression it would be hard to find. Our boy Frank is so unheroic as to barely grunt out a response that shall give his father to understand that he has heard him, and then he turns over and slumbers again. It is six o'clock. The first gray hints of the coming day have begun to penetrate the little chamber. The boy's clothing lies in a heap on the floor just where he jumped out of it in his haste the night before to get out of the frosty atmosphere and into his bed. In one corner of the room is a decrepit chair, whose cane-seat bottom had some time ago increased its original leakiness to such a degree that it had been judged unsuited to the pretensions of the sitting-room below stairs, and been banished to the chambers. An old trunk with a cloth cover thrown over it, and a stand with a cracked little mirror above, are the other most striking articles of furnishing. The walls of the room are not papered, and where the bed stands the bedposts have bruised the plaster so that you catch a glimpse or two of the lath behind. Yet the walls are not so bare as they might be, for the vacant space is made interesting by a large, legal-looking certificate that affirms that the boy's father, by the payment of thirty dollars, has been made a life member of the Home Missionary Society. The boy is rather proud of this fact; for, though he does not know what it all means, he feels sure it is something good and religious. He often reads the certificate, and ciphers out the names of the distinguished men who have put their signatures at the foot of the document; and he likes to look at the Bible scene pictured at the top, and takes pleasure in the elaborate frame, all made out of hemlock and pine cones. He is tempted to the belief that he is blessed above most boys in having a father who has the honor to be a life member of the Home Missionary Society, and who possesses such a certificate in such a frame, Indeed, he has gone much further than this upon occasion, and has complaisantly concluded that his folks were pretty sure of going to heaven in the end — at any rate, their chances were better than those of most of the neighbors. He knew very well his folks were more religious than most, and wasn't his father a life member of the Home Missionary Society? Our boy did not think these thoughts on New-Year's morning. Getting-up time came while it was still too dark to make out much besides the dim shapes of the articles about the room. Even the gayly colored soap advertisement he had hung next to the missionary certificate was dull and shapeless, and the garments depending from the long row of nails in the wall at the foot of the bed could not be told apart.  The morning scrub at the sink The morning is very cold. The window panes are rimed with frost, so that hardly a spot of clear glass remains untouched, and there is a cloudy puff of vapor from among the pillows with the boy's every outgoing breath. The boy's father, after he had properly warned his son of the approach of day, made the kitchen fire and went out to the barn to feed the cattle. When he returns to the house he appears to be astonished that Frank has not come down, though one would think he might have got used to it by this time. He stalks to the upstairs door and says, in tones whose sternness seems to prophesy dire things if not met with prompt obedience: "Frank! don't you hear me? I called you a quarter o' an hour ago. I want you to get up right off!" "Comin'," says Frank, and he rubs his eyes and tries to muster resolution to get out into the cold. "Well, it's 'bout time!" returns his father, "and you better be spry about it, too." When you sleep on a feather bed it lets you down into its yielding mass, so that if you have enough clothes on top you can sleep in tropical contentment. There is no chance for the frost to get in at any of the corners. Frank felt that his happiness would be complete were he allowed to doze on half the morning in his snug nest, but he knew it was hopeless aspiring to such bliss, and a few minutes later he appeared down-stairs, and the way he appeared was this: his hair was tumbled topsy-turvy, his eyes had still a sleepy droop, and he was in his shirt sleeves and stocking feet. He had no fondness for freezing in his room any longer than was necessary after he was once out of bed, and he always left such garments as he could spare down-stairs by the stove. Of course, he had not washed. That he would do just before breakfast, at the kitchen sink, after the outdoor work was done. The half-dressed boy, as soon as he gets down-stairs, hastens to make friends with the sitting-room stove, where a fire, with the aid of "chunks," has been kept all night. A light is burning in the kitchen, and his mother is clattering about there, thawing things out and getting breakfast. The boy hugs the stove as closely as the nature of it will allow, and turns himself this way and that to let the heat soak in thoroughly all around. Then he puts on the heavy pair of shoes he left the night before in a comfort able place back of the stove, gets his collar on, and his vest and coat, pulls a cap down over his ears, and shuffles off to the barn.  Late to supper Frank is thirteen years old, but he has been one of the workers whom it has seemed necessary to stir out the first thing in the morning for years back. He knew how to milk when he was seven, and he began to bring in wood — a stick at a time — about as soon as he could walk. He did not grumble at his lot nor think it a hard one, nor would he had it been ten times worse. Indeed, children, unless set a bad example by the complaining habits of their elders, or because they are spoiled by petting and lack of employment, accept things as they find them, and make the best of them. Even the farm debt, which may burden the elders very heavily and keep all the family on the borders of shabbiness for years, makes but a light and occasional impression on the youngsters. Then as to those accidents that are continually happening on a farm, and that are so heart-breaking and discouraging to the poorer ones — the collapse of a wagon, the sickness of the best cow, the death of the old horse, the giving out of the kitchen stove so that a new one is absolutely necessary; the children may shed a few tears, but work, and the little pleasures they so readily discover under the most untoward conditions, soon make the sun shine again and the mists of trouble melt into forgetfulness.  In the January thaw — wet feet Boys on small farms which have only two or three cows do not milk regularly — the father or an older brother does it; but if the rest of them are away from home or too busy with other work, the boy is called upon. Perhaps the father has to go so many miles over the hills to market, that he will not get home until well on in the evening. In that case you find the boy at nightfall poking about the glooms of the barn with a lantern, and doing all the odd jobs that need to be done before he can milk. When these are finished, the little fellow gets the big tin pail at the house, hangs his lantern on a nail in the stable, and sits down beside one of the cows. He sets the milk streams playing a pleasant tune on the resonant bottom of the pail, and from time to time snuggles his head up against the cow for the sake of the warmth. If the cow gives a pailful, his knees begin to ache and shake with the weight of the milk before he has done, and his fingers grow cramped and stiff with their long-continued action. However, the boy always perseveres to the end; and if, when he takes the milk in, his mother says he has got more than his pa does, he grows an inch taller in conscious pride of his merits. There is a difference in cows. Some require a good deal more muscle than others to bring the milk; some are skittish. One of these uneasy cows will keep whacking you on the ear with her tail every minute or two all through the milking, and at the same time the coarse and not overclean tuft of hair on the end will go stinging along your cheek. Then the cow will be continually stepping away from you sidewise, and you have to keep edging after her with your stool. These unexpected and uncalled-for dodges make the streams of milk go astray. And you get your overalls and boots well splashed as one of the results; another is that you lose your temper, and give the cow a fierce rap with your fist. That makes matters worse instead of better. The cow seems to have no notion of what you are chastising her for, and gets livelier than ever, It sometimes happens, in the end, that the cow gives the boy a sudden poke with a hind foot that sends him sprawling — pail, stool, and all. Then the boy feels that his cup of sorrow has run over; he knows that his pail of milk has. When a boy gets into trouble he always feels that the best thing he can do is to go and hunt up his mother. That is what our boy who met disaster in the cow-stable did. He left his lantern behind, but he carried in the pail with the dribble of milk and foam that was still left in the bottom. His mother was cutting a loaf of bread on the supper-table "Are you through so soon?" she asked. "Why, Johnny, what's the matter?" she says, noticing his woe-begone face. "The cow kicked me!" replies Johnny. His mother gets excited, and steps over to examine him, "Well, I should say so!" she exclaimed, "You're completely plastered from head to foot. Spilt all the milk, too, didn't it? Well, well, what's the matter with the old cow?" "I don' know," replied Johnny tearfully. "She just up and kicked me right over." "Well, now, Johnny, never mind," said his mother soothingly, "You needn't try to milk her any more to-night, You better tie her legs together next time when you milk. She's real hateful, that cow is. I've seen the way she'll hook around the other cows lots of times. Here, you run into the bedroom, and I'll get your Sunday clothes for you to change into. Wait a minute till I lay down a newspaper for you to put your old duds onto." A little later Johnny went out to the barn and brought in the lantern. Then he sat down to supper, and by the time he had eaten ten mouthfuls of bread and milk he felt entirely comforted and blissful after his late trials.  Sliding by the riverside The boy's usual work at night was to let the cows in from the barnyard where they had been standing, to get down hay and cut up stalks for them, water and feed the horses, bring in wood, not forgetting kindlings for the kitchen stove and chunks to keep the sitting-room fire overnight, and, last but not least, he had to do all the odd helping his father happened to call on him for. The boy enjoyed most of this, more or less, but his real happiness came when work was done and he could wash up and sit down to his supper, The consciousness that he had got through the day's labor, the comfort of the indoor warmth, the keen appetite he had won — all combined to give such a complaisancy, both physical and mental, as might move many a grown-up and pampered son of fortune to envy. The boy usually spends his evenings very quietly. He studies his lessons on the kitchen table, or he draws up close to the sitting-room fire and reads a story paper. There is not so much literature in the average family but that the boy will go through this paper from beginning to end, advertisements and all, and the pictures half a dozen times over. In the end, the paper is laid away in a closet up-stairs, and when he happens on dull times and doesn't know what else to do with himself, he wanders up there and delves in this pile of papers. He finds it very pleasant, too, stirring up the echoes of past enjoyment by a renewed acquaintance with the stories and pictures he had found interesting long before. Evenings are varied with family talks, and sometimes the boy induces his grandfather to repeat some old rhymes, tell a story, or sing a song. When there are several children in the family things often become quite lively of an evening. The older children are called upon to amuse the younger ones, and they have some high times. There are lots of fun and noise, and squalling, too, and some energetic remarks and actions on the part of the elders, calculated to put a sudden stop to certain of the most enterprising and reckless of the proceedings.  Comfort by the fire on a cold day. The baby is a continual subject of solicitude. His tottering steps give him many a fall, anyway, and he aspires to climb everything climbable; and if he doesn't tumble down two or three times getting up, he is pretty sure to do it after the accomplishment of his ambition. Then he makes astonishing expeditions on his hands and knees. You feel yourself liable to stumble over and annihilate him almost anywhere. The parents realize these things, and is it any wonder, when the rest of the flock get to flying around the room full tilt, that they become alarmed for the baby, and that their voices get raspy and forceful? Blindman's buff and tag and general skirmishing are not altogether suited to the little room where, besides the chairs and lounge and organ, there is a hot stove and a table with a lamp on it.  Doorstep pets. You need some practice to get much satisfaction from a conversation carried on amid the hubbub. You have to shout every word; and if the children happen to have a special fondness for you, they do most of their tumbling right around your chair. Some of the children's best times come when the father and mother throw off all other cares and thoughts, and become for the time being their companions in the evening enjoyment. What roaring fun they have when papa plays wheelbarrow with them, and puzzles them with some of the sleight-of-hand tricks he learned when he was young; or when mamma becomes a much-entertained listener while the oldest boy speaks a piece, and rolls his voice, and keeps his arms waving in gestures from beginning to end! The other children are quite overpowered by the larger boy's eloquence. Even the baby sits in quiet on the floor, and lets his mouth drop open in astonishment. The mother is apt to be more in sympathy with these goings on than the father, and I fancy it is on such occasions as he happens to be absent that they have most of this sort of celebration. At such a time, too, the children wax confidential, and tell what they intend to be when they grow up: this one will be a storekeeper, this one will be a minister, this one a doctor, this one a singer. They all intend to be rich and famous, and to do some fine things for their mother some day. They do not pick out any of the callings for love of gain primarily, but because they think they will enjoy the life. Indeed, when Tommy said he was going to be a minister, the reason he gave for this desire was that he wanted to ring the bell every Sunday. Bedtime comes on a progressive scale, gauged by the age of the individual. First the baby is metamorphosed and tucked away in his crib; then the three-year-old goes through a lingering process of preparation, and, after a little run in his nightgown about the room, he is stowed away in crib number two, and his mother sings him a lullaby, or a song from Gospel Hymns, and that fixes him for the night. These two occupy the same sleeping room as the parents, and it adjoins the sitting room. The door to it has been open all the evening, and it is comfortably warm.  Bringing in wood Girls and boys of eight or ten years old will take their own lamps and march off to the cold upper chambers at eight o'clock or before. Some of the upper rooms may have a stovepipe running through, which serves to blunt the edge of the cold a trifle, or there may be a register or hole in the floor to allow the heat to come up from below; but, as a rule, the chambers are shivery places in winter, and when the youngsters jump in between the icy sheets their teeth are set chattering, and it is some minutes before the delightful warmth which follows gains its gradual ascendency. The boy who sits up as late as his elders is usually well started in his teens. The children are not inclined to complain of early hours unless something uncommon is going on. They are tired enough by bedtime. Even the older members of the family are physically weary with the day's work, and the evening talk is apt to be lagging and sleepy in its tone, and the father gets to yawning over his reading, and the mother to nodding over her sewing. Many times the chiefs of the household will start bedward soon after eight; and as to the growing boy, he usually disregards the privilege of late hours, and takes himself off at whatever time after supper his tiredness begins to get overpowering. It would be difficult to say surely that the boy's room I described early in this chapter was an average one. The boy is not coddled with the best room in the house. In some dwellings the upper story has but two or three rooms that are entirely finished. The rest is open space roughly floored, and with no ceiling but the rafters and boards of the roof. There are boys who have a bed or two in such quarters as these, or in a little half-garret room in the L. These unfinished quarters are the less agreeable if the roof happens to be leaky. Sounds of dripping water or sifting snow within one's room are not pleasant. On the other hand, there are plenty of boys who have rooms with striped paper on the walls, and possibly a rag carpet under foot, not to speak of other things no less ornate. In the matter of knickknacks, most boys do not fill their rooms to any extent with them — the girls are more apt to do this. But a boy is pretty sure to have some treasures in his room. He is not very particular where he stows them, and he is likely to have some severe trials about house-cleaning time. His mother fails to appreciate the value of his special belongings, and is not in sympathy with his method of placing them. They get disarranged and thrown away. If fortune favors the boy with the drawers of an old bureau, he is fairly safe; but things he puts on the shelf and stand, and especially those he puts right along there in a row under the head of the bed — oh, where are they?  Coasting A winter breakfast on a farm is over about sunrise. All the rolling hills near and far lie pure and white beneath the dome of blue, and they sparkle with many a frosty diamond, and sunward gleam with dazzling radiance. I doubt if the boy cares very much about this. He is no stickler for beauty. Questions of comfort and a good time lie uppermost in his mind. Nature's shifting forms and colors and movements affect him usually but mildly as a matter of beauty or sentiment, though in a simple way many things touch him to a degree; but commonly the phase that presents itself uppermost is a physical one. The sun shines on the snow — it blinds his eyes. A gray day is the dismal forerunner of a storm. Sunsets, unless particularly gaudy, have no interest, except as they suggest some weather sign. He delights more in days that are crystal clear, when every object in the distant hills and valleys stands sharply distinct, than in the mellow days that soften the landscape with their gauzy blues. He loves action, not dreams. Boys, like animals, feel a friskiness in their bones on the approach of a storm. They will run and shout then for the mere pleasure of it, and play, of whatever sort, gets an added zest. It may be the dead of winter, but that does not keep them indoors. If the wind blows a gale and whistles and rattles about the home buildings and makes the trees crack and creak, so much the better. Nor will the onset of the storm itself drive them indoors. The whirling flakes may increase in number till they blur all the landscape, and go seething in shifting windrows over every hillock; yet it will be some time before the children will pause in their sliding, skating, or running to think of the indoor fire.  Winding the clock When they do go in, it is as if all the out-of-door breezes had gained sudden entrance. They all come tumbling through the door with a bang and a rush, and there is a scattering of clinging snow when they pull off their wraps and throw them into convenient chairs or corners. They declare they are almost frozen as they stamp their feet about the kitchen fire, and hug their elbows to their bodies and rub their fingers over the stove's iron top. "Well, why didn't you come in before, then?" asks their mother. "Oh, we was playing," is the answer. "We been having a lots of fun. The snow's drifted up the road so it's over our shoes now." "You better take off your shoes, if you've got any snow in 'em," the mother says. "I declare, how you have slopped up the floor! And you've made it cold as a barn here, comin' in all in a lump that way. — Here, Johnny, don't you go into the sittin' room till you get kind o' dried off and decent." "I just wanted to get the cat," says Johnny. "Well, you can't go in on the carpet with such lookin' shoes, cat or no cat!" is his mother's response. Meanwhile she has taken her broom and brushed out on the piazza some of the snow lumps and puddles of water the children have scattered. The indoor stoves are an important item in the boy's winter life. It is a matter of perpetual astonishment to him how much wood those stoves will burn. He has to bring it all in, and he finds it as much of a drudgery as his sister does the everlasting washing and wiping of dishes. It is his duty to fill the wood-boxes about nightfall each day. The wood shed is half dark, and the day has lost every particle of glow and warmth. He can rarely get up his resolution to the point of filling the wood-boxes "chuck full." He puts in what he thinks will "do," and lives in hopes he will not be disturbed in other plans by having to replenish the stock before the regulation time the night following. Sometimes he tries to avoid the responsibility of a doubtfully filled wood-box by referring the case to his mother. "Is that enough, mamma?" he says. "Well, have you filled it?" she asks. "It's pretty full," replies the boy. "Well, perhaps that'll do," responds his mother sympathetically, and the boy becomes at once conscience free and cheerful. All through the day, when the boy is in the home neighborhood, he is continually resorting to the stoves to get warmed up. Every time he comes in he makes a few passes over the stove with his hands, and he must be crowded for time if he can not take a turn or two before the fire to give the heat a chance at all sides. If he has still more leisure, he gets an apple from the cellar, or a cooky from the pantry, and eats it while he warms up; or he goes in and sits by the sitting-room stove and reads a little in the paper. One curious thing he early finds out is, that he gets cold much quicker when he is working than when he is playing. Probably the majority of New England boys spend most of the winter in school; though in the hill towns, where roads are bad and houses much scattered, the smaller schools are closed. While he attends school the boy has not much time for anything but the home chores; but on Saturdays, and in vacation, he may at times go into the woods with the men. There is no small excitement in clinging to the sled as it pitches along through the rough wood roads amid a clanking of chains and the shouts of the driver. The man, who is familiar with the work, seems to have no hesitation in driving anywhere and over all sorts of obstacles. The boy does not know whether he is most exhilarated or frightened, but he has no thought of showing a lack of courage, and he hangs on, and when he gets to the end of the journey thinks he has been having some great fun.  On the fence over the brook The boy has his own small axe, and is all eagerness to prove his virtues as a woodsman. He whacks away energetically at some of the young growths, and when he brings a sapling four inches through to the ground he is triumphant, and wants all the others to look and see what he has done. He finds himself getting into quite a sweat over his work, and he has to roll up his earlaps and get his overcoat off and hang it on a stump. Then he digs into the work again. In time the labor becomes monotonous to him, and he is moved to tramp through the snows and investigate the work of the others. There is his father making a clean, wide gash in the side of a great hemlock. Every blow tells, and seems to go just where he wanted it to. The boy wonders why, when he cuts off a tree, he makes his cut so jagged. He stands a long time watching his father's chips fly, and then gains a safe distance to see the tree tremble and totter as the opposite cuts deepen, at the base, near its heart. What a mighty crash it makes when it falls! How the snow flies and the branches snap! The boy is awed for the moment, then is fired with enthusiasm, and rushes in with his small axe to help trim off the branches. After a time there comes a willingness that his father should finish the operation, and he wanders off to see how the others are getting on. By and by he stirs up the neighborhood with shouts to the effect that he has found some tracks. His mind immediately becomes chaotic with ideas of hunting and trapping. Now that he has begun to notice, he finds frequent other tracks, and some, he is pretty sure, are those of foxes and some of rabbits and some of squirrels. Why, the woods are just full of game! — he will bring out his box trap to-morrow, and the certainty grows on him that he will not only get some creatures that will prove a pleasant addition to the family larder, but will have some furs nailed up on the side of the barn that will bring him a nice little sum of pocket money. That evening he brought out the box trap and got it into practice, and made all the younger children wild with excitement over the tracks he had seen and his plans for trapping. They all wanted a share, and were greatly disappointed the next day when their father would not let them go too. The boy set his trap, and moved it every few days to what he thought would prove a more favorable place, but he had no luck to boast of. Yet he caught something three times. The first time he had the trap set in an evergreen thicket in a little space almost bare of snow. He was pleased enough, one day, to find the trap sprung, and at once became all eagerness to know what he had inside. He pulled out the spindle at the back and looked in, but the tiny hole did not let in light enough. Very cautiously he lifted the lid a trifle. Still nothing was to be seen, and he feared the trap had sprung itself. When he ventured to raise the lid a bit more, a little, slim-legged field mouse leaped out. The boy clapped the lid down hard, but the mouse hopped away, and in a flash had disappeared in a hole at the foot of a small tree. The boy was disappointed in having even such a creature escape him.  Rubbing down old Billy The next time, whatever it was he caught gnawed a hole through the corner of the box, and had gone about its business when our boy made his morning visit to the trap. Then he took the trap home and lined the inside with tin. He had no luck for some days after, and finally forgot the trap altogether. It was not till spring that he happened upon it again. He felt a tingle of the old excitement in his veins when he saw that the lid was down. He opened it with all the caution born of experience, but the red squirrel which was within had been long dead; and when the boy thought of its slow death by starvation in that dark box, he felt that he never would want to trap any more in that way.  A drink of sap The boy finds the woods much more enjoyable than the woodpile when it is deposited in the home yard. He knows that as long as there is a stick of it left he will never have a moment of leisure that will not be liable to be interrupted with a suggestion that he go out and shake the saw awhile. The hardest woods, that make the hottest fires, are the ones that the saw bites into most slowly and are the most discouraging. The best the boy can do is to hunt out such soft wood as the pile contains, and all the small sticks. He makes some variety in his labor by piling up the sawed sticks in a bulwark to keep the wind off, only it has to be acknowledged that he never really succeeds in accomplishing this purpose. But the unsawed pile grows gradually smaller, and his folks are not so severe that they expect the boy to do a man's work or to keep at it as steadily. He stops now and then to play with the smaller children, and to go to the house to see what time it is or to get something to eat. Besides, his father works with him a good deal, and if there are times when the minutes go slowly, the days, as a whole, slip along quickly, and, before the boy is aware, winter is at an end if the woodpile isn't. |