| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

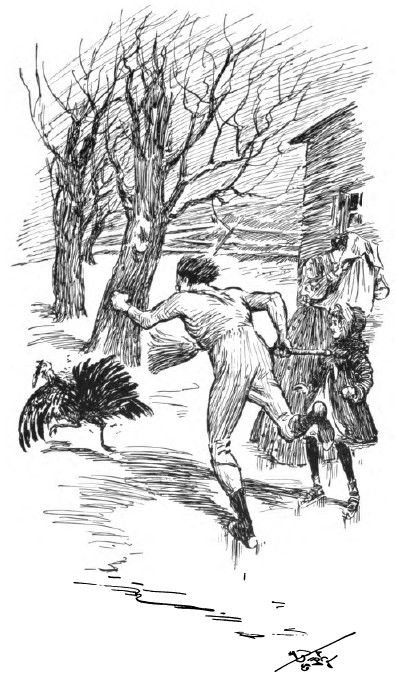

| CHAPTER XII TURKEYS AND A FOOTRACE DID you ever think that one of the main reasons of the difficulty our farmers have of realizing more than a moderate competency from the cultivation of a New England farm is the want of a good market? The cities and large towns are few in number and so small, and the Boston markets for farm products of the perishable kinds are supplied by the larger, nearer, and more fertile farms and market gardens of suburban towns. But for hardy perennials, such as chickens, ducks, lambs, goats, calves, and woodchucks, there is, and ever has been, a fairly good market, and much money has been made in the cultivation of such products. Thirty or forty years ago, and as far prior thereto as the memory of man runneth, even to the time the first white man landed in America and on the solar plexus of the amber-hued aborigine, the sound of the turkey was heard in the land and vied with the song of the birds, the nasal tones of the lusty husbandman berating his sluggish cattle, the bleating of sheep, the lowing of cattle, and the grunting and squealing of fat pigs, all of which went to make up a pastoral symphony or bucolic tout ensemble. Daily the flock of bronze beauties descended to the fields and woods, where they industriously put in from twelve to fourteen working hours in hunting down grasshoppers, katydids, crickets, and other vermin, and nightly did they festoon the apple trees, the roofs of sheds and barns, and the seats of farm-wagons with their plump bodies. In those days the raising and marketing of turkeys formed one of the principal sources of income for the farmer or the farmer's helpmeet. They were raised in two ways. The most profitable method was to enter your neighbor's orchard when the family were asleep, and carefully and without noise raise the drowsy turkeys from their roosting places, and market them in a distant county before morning broke. The element of chance that entered into the transaction and occasionally involved those interested in this industry in expensive legal proceedings rendered this method slightly unpopular, although the percentage of profit was very considerable. The other and more popular method was to allow the woman of the household to take entire charge of the flock, and to hold the proceeds for her personal use and adornment. To this circumstance the beautiful sables that have been handed down in country families owe their origin. Our grandmothers, great- and great-great-grandmothers developed great fleetness of foot in avoiding the lightning charge of irate cock-turkeys weighing forty or more pounds, and a wide range of geographical knowledge in seeking and housing the immature flocks when a rain-cloud appeared on the horizon. Indeed, many of our long-distance pedestrians and short-distance sprinters of to-day have come to their full powers by a careful cultivation of a direct inheritance from athletic great-great-grandmothers. But of late years turkey-raising as a local industry has not flourished, and the New Hampshire turkey is almost extinct. What is the reason? One has it that the increasing liberality of the modern farmer husband is such that his wife obtains her heart's desire simply for the asking, and is not obliged to raise live-stock for a living. Another, that marriages between the different sexes in the turkey family have been allowed within those degrees of consanguinity that in the human species are prohibited by law, and the result has been the production of a race of turkey degenerates predisposed to paresis, suicide, and kindred ills. Still another says that an insect known as the borer, equipped with a cast-iron, auger-like proboscis, working on a swivel, bores holes in the bird's crop and lets its contents exude with the innocent life of the victim. This man affirms that another insect bores into the ears of the young bird and drives it to suicide. One says it is over-feeding, another starvation. One advises leaving the birds to nature, another, highly artificial measures. It reminds me of the old definition of climate as given by our old friend Guyot's "Common School Geography." "Climate is heat and cold, moisture and dryness, healthfulness or unhealthfulness." I well remember my childish wonder that one term could embrace so many contrary characteristics. In thinking matters over, I finally became convinced that the opportunity had arrived to make my name, like that of our national emblem, "Known and honored throughout the world." To invent, discover, and develop, to patent or copyright a process for preserving the life of the New Hampshire turkey, was to put it into the power of every farmer to remove the mortgage from his ancestral acres, to put money in his purse, to give his daughters lessons in elocution, and to allow his wife to join the "Daughters," and to live happy ever afterwards. Perhaps as "Shute, the turkey man," my name might go pinwheeling through the ages to come, neck and neck with the names of Buffalo Jones, Scroggs the Wyandotte man, the inventor of Mennen's Toilet Powder, and kindred celebrities. So I invested in a pair of mammoth bronzes that were displayed in a window of a Boston store, and awaited their arrival with ill-concealed anxiety. For three nights subsequent to the purchase of the birds I drove to the station with a huge crate, which I had fastened to the pung so firmly that it prevented me from using the sleigh for any other purpose, and for three nights I returned disappointed. On the fourth night I found them waiting in a crate fully as large, upon which freight-bills were due sufficient to freight a horse to the Pacific slope. This, with the amount already paid for the birds, made my original investment somewhat disquieting. However, I loaded the new crate on the old one, tied it as well as I could with the hitch-rope, climbed stiffly to the seat, and started for home. Respected reader, did you ever try to drive a hard-bitted horse with one hand and hold in two crates weighing about a ton each, and laden with shifting ballast in the shape of agile and wildly terrified turkeys? It is a trick, let me tell you. I covered the distance between the station and my house in several seconds less than the record, and pulled both arms a foot or more beyond their normal reach while so doing. I was so anxious to release my turkeys that I neglected to unhook the mare, and when after considerable difficulty I dragged forth the cock-turkey by one hind-leg, he beat my hat over my ears with his huge wings, covered me with dust and dirt, and so frightened the mare that she went through the narrow door like a flash of lightning, leaving a pung with broken shafts and a goodly part of the harness on the outside. I was too much occupied with the turkey to pay much attention to the mare, and after a brief season of collar-and-elbow, Græco-Roman, hitch-and-trip, and catch-as-catch-can, I dragged the unwilling old bird from his retirement, left him in the loft, swelling and spreading, and dashed down after the hen, suddenly reflecting that I had left the crate open. I found her standing in the open, with outstretched neck and tail half-spread. Awed by my commanding appearance, or possibly by the fact that I had so many feathers on me that she mistook me for a strange turkey-cock of disreputable appearance, she started off at a high rate of speed and I followed at a hand-gallop. The going was heavy and I soon overtook her, fell over her prostrate body, half-buried in the snow, and arose with her clasped to my bosom. Before I could catch her by the legs she, with ill-directed but vigorous clawings, gouged a long strip from my countenance, leaving an unsightly scar that remained for several weeks, and gave rise to the rumor that my home life was unhappy. She was not nearly as handsome or as heavy as her mate, but that she was dear to him he demonstrated by furiously attacking me when I appeared in the loft, and tearing a large hole in my trousers, in return for which I kicked him several yards with some considerable deftness, and left him to smooth his ruffled plumage and temper, while I sought warm water, Pears' soap, court-plaster, and a clothes-brush. As it was early in March, when cock-turkeys are about as savage as four-year-old Jersey bulls, I warned the different members of our family to give him the right of way. I soon found that he was at heart a most pusillanimous poltroon, for a small gamecock that roosted in the loft, so far from being terrified by his appearance and loud boasts, thoroughly whipped him, and drove him headlong down one of the grain chutes, whence we rescued him by tearing away the planks, empurpled and nearly dead from a rush of blood to the head. Although an arrant coward, he put up such a menacing front, boasted so loudly, and turned so red-faced in his anger that he impressed the members of my family, the neighbors, and the populace generally, as a very dangerous antagonist. My daughter, like her father extraordinarily gifted in the way of legs, had no difficulty in distancing the old fellow, and dodging his fierce rushes, and the daily sight of a very funny young lady with spindly legs flying across the yard pursued by a red-faced, gobbling turkey, added much to the interest with which the neighborhood viewed him. My wife, however, had no patience with the young lady or any one else who was afraid of an old turkey, and expressed great confidence that the day old Tom came at her would be a very sad day for the poor old fellow. This naturally made me look forward to the inevitable meeting between the mistress of the house and the master of the yard as a prospective treat. One day I was in the barn and saw the usual stern chase swinging its way across the yard. Scarcely had the house-door slammed before it opened again, and there strode forth, with firm step and resolute manner, the lady of the house with the light of high purpose and the glint of warlike determination beaming through her specs. The old cock had retired some distance from the house, but drew up as the apparition approached. As the meeting promised to be of some interest, I peeped through a window and prepared to get as much enjoyment out of the engagement as the nature of the circumstances would allow. Straight toward old Tom came the lady with rapid and measured strides. Instantly he hoisted his tail, injected about a quart of scarlet war-paint into his head and neck, stuck every feather on end, and let out a fierce rolling gobble. The walk slowed down a bit, and the lady cut her smile of confidence down one half, but still advanced warily. The gobbler then made a whining imitation of a watchman's rattle, laid the feathers of his neck flat until his head looked snaky, and took a few side steps toward his visitor. "Shoo, you nasty thing! Shoo!! scat!!! go away!!!!" screamed the lady, stopping abruptly. Old Tom whined like a dog, ending with a sort of bass croak that seemed to come from the pit of his stomach, then took a few more steps forward on tiptoe, and sounded the watchman's rattle, winding up with a fierce gobble. "Go away, you nasty thing! Shoo!! scat!!!" shrieked the lady. "Oh, why don't somebody come? Oh-ee!! Oh-ee!! Get away!!" she shrieked vigorously, and somewhat improperly shaking her skirts, with marked scenic effect. This was the chip on the shoulder, the challenge that an adult male turkey always takes up. With outstretched neck and hideous whine he charged, and with shrill shrieks the lady fled for the friendly shelter of the open portal. I have ridden on the "Flying Yankee," I have flashed down the toboggan slide, have shot or "shooted" the chutes, have twice been run away with when astride a bronco, have seen the fastest sprinter breast the tape in an even ten, have seen the two-minute pacer coming down the stretch abreast the thoroughbred runners, but never have I seen such a burst of speed as my wife put on that day. She fairly whizzed across the yard and disappeared into the house like a flash of jagged lightning, and the bang with which she slammed the door, echoed and reechoed and drowned my coarse and unfeeling laughter and the delighted giggle of my irreverent daughter, who from a convenient window had viewed the proceedings with great enjoyment. Truly this turkey business was not a bad investment after all. As spring approached, my turkey began to lay large pock-marked eggs with exceedingly rough shells, which I carefully secured and concealed from the prying eyes of the cook. As soon as I had a sufficient number, I set them under two large fluffy hens and sternly repressed the maternal instinct of the turkey-hen, daily removing her forcibly, protestingly, flappingly from her nest under a pile of brush, where she persistently sat on a couple of bricks. In due time the eggs under the hens hatched and the bricks under the turkey refused to hatch, but the enthusiasm of the old turkey-hen continued unabated. She seemed determined to hatch out terra cotta images, drain-tile, or something. The little turks or poults were delightful little wild things, beautifully mottled, and on them I lavished the affection of a warm and ardent nature. On one of them, as an experiment, I lavished something even more ardent, for under the advice of a Granger friend I introduced a peppercorn into the epiglottis of an infant turk and watched the effect. It was instantaneous. The poor bird piped a shrill protest, turned flip-flaps, hand-springs, and cart-wheels, opened its beak, clawed at it with frenzied feet, rolled, ran, fell, and finally collapsed into a piteous little ball of down and died. This experiment, at least, was not a success, except as an exterminator, and I had but fifteen poults instead of the original sixteen. I then put them in a well-sheltered place and fed them according to the best standards. For a while all went well. They grew and throve, and I became very complacent over the matter. Too much so, I am afraid, for on my return from the office one day I found three of them suffering from melancholia, with heads sunk on their breasts, and apparently indifferent to their surroundings. I at once powdered them thoroughly with insect powder, under which drastic treatment they promptly died without struggle or squeak. A week later, four more passed peacefully away without apparent reason, and a week later cholera attacked the remainder. One by one they passed to the great hereafter. We found them in all places, in all positions. Some on their backs, with their feeble little claws outstretched in air, some huddled into corners, with heads drawn back over their shoulders, some curled up like balls of fur. In vain I tried all the remedies in the poultry papers and in books. In vain I consulted wise sages and oracles in poultry-culture. It was useless; those turks were doomed from the moment of their entrance into a sinful world. In a month from their arrival nothing remained but bitter memories and a very inconsiderable addition to my compost-heap. In the meantime the old cock, having much unoccupied time on his hands, and pining for the society of his wife, who was still sitting on the bricks under the brush-heap, was occupied in chasing defenseless women from the premises. Scarcely a day passed without a sally and a rescue. In his blundering, well-meaning way he was doing a deal of good. The female book agent and subscription fairy fled from my premises as from a place accursed. The dark-complexioned lady of Armenian extraction, with big feet and still bigger suit-case, crowded to the brim with gaudy and useless wares, was driven from the premises instanter. The saturnine villain with parti-colored rugs had to fly for his life. The small boys, who had worn a path through my lawn to the campus, were forced to pass through a neighbor's garden, and the D'Indy Club, the Frauenverein, the Mothers' Club, the committee on church affairs, met elsewhere. Really, I was quite ready to repeat my experiment should anything happen to my old friend, and stood ready to advocate the cock-turkey as the watch-dog of the household. One day, as I was passing the brush-heap, I bethought myself of taking a look at the turkey-hen. So I pulled her hissing from her nest, and to my surprise found that the bricks had been pushed from the nest, and in their place were eight eggs. With a thrill at my heart that reminded me of my boyish days of birds'-egging, I replaced her carefully and took heart again. Perhaps I had made a mistake after all. Perhaps the books were wrong. I remembered to have heard a story once of an Irish common councilman, who in a somewhat acrimonious debate as to how many gondolas should be bought for the pond in a public park, sturdily advocated the purchase of a male gondola and a female gondola, "an' t' lave th' rist t' nature," as a measure calculated to minimize expense. Would it not be better to discontinue the artificial methods and "lave th' rist t' nature"? I would try. It couldn't be any worse. I couldn't lose any more than the whole brood. Couldn't I? Wait a bit. In due time every egg hatched, and the mother turkey cautiously crept out, suspicious of every sound, watchful of every movement. That night they disappeared in a grove back of my lot. The next morning I arose betimes, or a full hour and a half before betimes, and stole into the silent wood. Joy! at the foot of a huge pine I found her and her tiny babies, safe, sound, and dry, although a smart shower had left everything dripping. It was a success. She alone had the secret of nature. Away with artificial methods. Return to nature. Strange how besotted man gets in his ignorance. But for blind adherence to experiment, the New Hampshire turkey — "Might have stood against the world,Now none so poor to do him reverence." Wait a bit: that night at dusk I stole again into the forest, and to the foot of that mighty pine. She was not there, neither were her chicks. The mother love, suspicious, primeval, alert, had prompted her to find a new hiding-place. I would pit my wits against hers. Not to interfere with nature, but to keep her in sight, to study her cunning, to learn her secret. I hunted so long that night that on my return in the darkness I bumped into trees and stubs, — "I scratched my hands, and tore my hair,But still did not complain." The next morning at daybreak, and the next night at dusk, and for many, many weary days and nights, I searched, and peered, and sneaked, and spied, and climbed trees, and skinned and barked and abraded myself in various tender places. "Donafi lived, and long you might have seenAn old man wandering as in search of something, Something he could not find, he knew not what." In vain my search. I never saw her again, nor did I ever see her chicks, and to this day their disappearance is a mystery. It seemed to me that the old cock sympathized with my grief. At least he did not seem the same turkey, and he began to follow me around. It may have been that he was considering the advisability of giving me a poke with his iron beak. But if so, he never did. Time passed. The haying season arrived, waxed, and waned. Green corn, astrachan apples, Sanford's Jamaica Ginger, and allopathic physicians battled for the lives of our dear ones; Colorado beetles cut my potato-tops to the ground, rose-bugs in flying swarms devastated my "jacks." In short, from morning to night the whole household was engaged in a hand-to-hand struggle to rescue our feeble crops from their many enemies. Constant occupation is good for grief and disappointment. In due time my cheerfulness returned. Old Tom conceived a violent passion for a diminutive bantam hen, and the memory of his erring or unfortunate mate faded. September came with its early crops, but I had no crops. October with its later harvests, but I gathered none. November merged into December; December into January. Old Tom began with the lengthening days to develop a savage temper. An early February storm had made ponds of our garden, and sharp weather had converted it into a fine rink, where my daughter spent her leisure hours. Shortly after the noon hour I was in my room, disrobed. I had just finished caring for my stable animals. Suddenly a series of loud screams startled me. I rushed to the window, pulled up the shade, and looked. Penned into a corner cowered my small daughter, while before her, scarlet of neck, swollen of wattles, with every feather on end, towered old Tom, furious and menacing. From the side porch the housemaid screamed hysterical advice, and jumped up and down in her excitement. I grabbed my trousers. They were wrong-side-out, and I got stuck in them, and fell to the floor. Gentle reader, did you ever try to pull on your trousers while the house was burning, and when the salvation of yourself or your loved ones depended upon speed? Try it some time and see how adroit you are. I threw them across the room, got on one shoe, and was groping under the bed for the other, when another cry of terror electrified me, and I dashed for the stairs. "For heaven's sake, aren't you going to put on some clothes?" screamed my wife; "the girl is out there." "Damn the girl!" I snapped; "if she can stand there and see that gobbler scare Nath. to death, I guess it won't hurt her to see me." And I shot down the stairs like an Andover quarterback going through a hole in the Exeter line. "The uniform 'e woreWas nothin' much afore An' rather less than 'alf o' that be'ind." I grasped a broom as I flew through the kitchen, turned the corner of the shed on one wheel, and dashed into the open with a whoop. At the unexpected appearance of so skinny a spectre clad in pale mauve underwear, stretched to its utmost tension by frantic straddles, the housemaid shrieked and threw her apron over her head, but I kept on. Arrived in time, I swung with all my strength on the gobbler's scarlet neck, but missed, and turning several times with the momentum, fell and rolled on the ice. I fairly bounced to my feet and dashed after the flying bird. Down the field we went, round the apple trees, the gobbler in the lead, just out of reach. Through the rose-bushes, which tore ravelings from my underwear and cuticle from my straining legs; round by the shed the chase continued, over the wood-pile, which turned and rolled on me, giving the gobbler a fresh start.  Dashed into the open But I picked myself up. I did not feel my bruises. Eliza crossing the ice was not more oblivious of her cut and naked feet. I was going to catch that gobbler if I broke something. No red-headed devil bird should menace the life of the child of my old age; and again I picked up my agile heels and flew. This time the wily old bird took me over a hard-frozen corn-field with stubs, but failed to shake me off. Neighbors threw up the windows and stared. People in passing teams stopped and cheered us on. The bird ran with drooping wings. He was about all in. So was I. Suddenly he stopped and squatted. I tried to stop, but could not, and fell with soul-shaking violence. When I sat up, the gobbler had crawled into the barn, and with the assistance of my wife and daughter, who draped me in a table-cloth, I returned to my room, regained my breath gradually, and resumed my clothing. Does any one wish to buy an adult male turkey? Weighs thirty pounds; is a direct descendant of the first turkey seen by the Pilgrim Fathers when they moored their bark on the wild New England shore. It may be the original turkey. I can't say. Turkeys are not in general valuable on account of their antiquity, but a genuine Stradivarius turkey, with Sheraton legs, Hepplewhite upholstery, and Chippendale varnish, of undoubted antiquity and undisputed ancestry, ought to bring a good price. At any rate, the turkey industry on the D. F. Ranch is hereby discontinued. |