| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2011 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

XIV

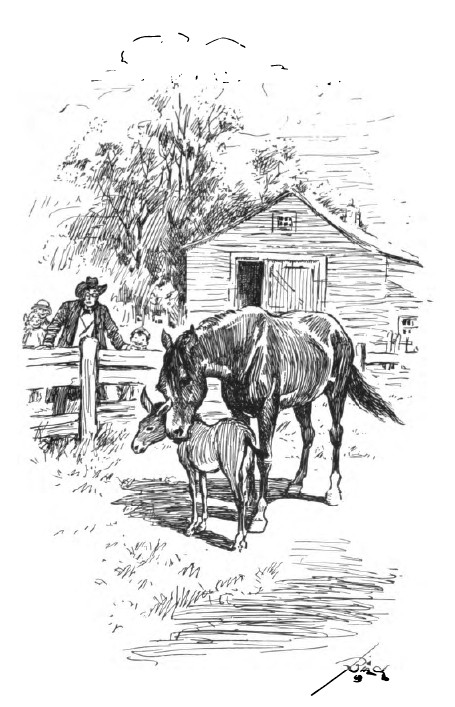

GREAT EXPECTATIONS ABOUT the Fourth of July my vegetable garden was in the most flourishing condition possible. My corn was thick and straight and green, my beets were bushy and the leaves purple and glossy. For weeks I had luxuriated in salad from my lettuce-rows, in radishes, exhumed from my own beds and cut into fancy shapes, and in pie-plant, which unfortunately I had received as courtesies from my neighbors, as my fatal error in treating my own plants as burdocks had prevented me from enjoying my own products. I had even gone to the extent of pulling a few potato-tops, hoping that their unusual development might have produced new potatoes of available size; but what I found were seemingly covered with warts and blisters, which rendered them extremely unattractive in appearance, and slimy and disagreeable to the touch. Shortly after the Fourth I engaged a man to mow the grass-crop. He appeared with an assistant, and after viewing the astonishing growth of pigweed and other worthless vegetation, they hung up their scythes and returned for bush-hooks, with which they swung and hacked all day, and then, having charged on a bush-hooking basis, which is one half larger price than plain mowing, they departed, after assuring me that the crop was of absolutely no value, which, as I had been so informed for about two hundred times, I knew perfectly. No long rains, no showers, no thunder-storms came to interfere with haymaking, which could scarcely have been the case had the crop been of value. But after I had collected the entire crop in one enormous pile it made a gorgeous bonfire, but left a black smooch on the green surface of my field that did not entirely disappear during the rest of the season. My strawberry-plants had grown surprisingly, but they demanded more of my time than almost all the other crops together. For although they grew very fast, they appeared to be on terms of intimacy with almost every sort of base weed, whose company they appeared to court, and who in turn were fondly embraced by the tendrils of their aristocratic acquaintances. Again, these strawberry-plants had the most astonishing fertility in sending out trailers or creepers or shoots, which, if not pruned, would in a very short time have converted the entire farm into an enormous bed of strawberry vines. I had six rows of these plants, and it was my custom every morning, just after finishing grooming Polly and Lady M. and Jack, to go down on my knees, and with a pair of shears prune one row of trailers before breakfast. Thus the beginning of the next week would find me at the starting-point, with just as many, if not more, trailers to cut and weeds to disentangle and pull up than ever before. However, I persevered with the hope of bountiful berries the second year. A few days after the Fourth we had a terrific storm of wind and rain which lasted all one night. The next morning, when the sun rose, I was early on hand to see the results of the storm on the garden. Although partially protected by a high board-fence, my corn was badly damaged and a good deal of it prostrate. My other vegetables had suffered less. I retired to the barn and communed bitterly with myself. "Ingenui, et duplicis tendens ad sidera palmas talia voce retuli: O terque quaterque beati quis ante ora patrum Troia sub moenibus altis contigit oppetere!'" Was it for this that I had worked, and slaved, and dug, and hoed, and pruned, and scratched, and raised blood-blisters on my hands? Was it for this that I had spent evening after evening with lantern, wheelbarrow, tub, pail and dipper, faithfully coaching the struggling plants through a dry spell? Was it for this that I had borne with calm disdain paternal scoff, uxorial jeer, and neighborly gibe? Then I went back and made an examination. None, or at least very few, of them were broken. I tried the experiment of straightening one plant and heaping earth round it to keep it straight. It was perfectly feasible. For an hour before tea, and after tea until late at night, with lantern I worked until every bent stalk was straightened. It was fully a week after that when Daniel, the omniscient, informed me that the stalks would have straightened out themselves. A day or two after, my friend Daniel called to see Lady M. and to determine whether or not it would be advisable to grant that blue-blooded animal a long holiday in view of the great event in her life, and, I also felt, in my fortune and reputation as a stock-farmer. By his advice Lady M. was given a vacation in the paddock, quite a pretentious name for an open shed with a fifty-foot run. It seemed as soon as she was turned into the lot that my expectations were almost realized. I am a little given to building air-castles, and I must confess that I looked forward to the possibility of breeding the two-minute trotter. I realized the extreme improbability of anything of the kind ever happening to me, and yet it was a possibility. Lady M. showed good breeding. There were strong evidences of the Morgan in her conformation, her courage, and her quiet, gentle ways. And when bred to Electric Jim (2.16 1/4), first dam Sukey M. (2.21), second dam Wilkes Jane (2.12 1/2), what record would daunt her foal. It might be — well, I had known men to get into the judges' stand for less reasons than that. I even might sit in the sulky and have a card with a number on it fastened to my sleeve. "Gentleman driver" was by no means a title without honor. Perhaps the many trials and losses I had suffered in my farm and garden investments might in a way be a sort of preparation designed to make me appreciate all the more my success as a horse-breeder, just as a man sometimes eats heartily of salt fish before attending a banquet at which wine is to flow freely. At all events, should her get not be a racer, the ownership of a finely bred, game roadster, with all that goes to make up a gentleman's driving outfit, would certainly afford me great pleasure, as would the casual mention of Electric Jim (2.16 1/4), first dam Sukey M. (2.21), second dam Wilkes Jane (2.12 1/4). True, I had never heard of these famous horses except in the advertisement referred to, but their records were unquestionably genuine, and some day when I had time enough I would look them up, and paste their records in my stud-book, which I anticipated buying as soon as the foal arrived. Every day was one of expectation. In the morning I was first at the paddock. At noon I hurried there from the office, and visited there the last thing at night. I arranged for my family to notify me by telephone. My friends and neighbors were nearly as much interested as I was, and waited in more or less anxiety for the event. For several weeks this went on. I do not know how I could have stood the strain had it not been for the fact that I was kept busy both by office and farm work. The corn silked and became a daily course on our table, and on those of our relatives and neighbors. My beans likewise helped maintain my reputation as a bon vivant, while some of my other crops were maturing in fine shape. It was, however, at the cost of constant labor to keep down weeds. Indeed, I do not believe I could have succeeded had it not been for the occasional assistance of Mike, who would accomplish in a day more than I would in a week. I forgot to say that during the month of June I had, literally, bushels of roses, which I distributed by the pailful among our friends, the successful cultivation of which (both friends and roses) kept my wife engaged in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter with all manner of creeping, crawling, climbing, and flying things. This was not a bad thing for me, for it took up so much of her waking hours as to leave me practically free from interference or even criticism in my employment of my time. About the middle of August I was called away from home to attend a hearing in a farming town about twenty-five miles distant, which could not be reached by rail. Consequently, I had to drive Polly, and as the hearing lasted three days, I was unable to return home at night. There were several lawyers connected with the case, and a large number of witnesses, several of whom stayed at the hotel where I was staying. In the evenings we would sit out on the hotel piazza and chat with one another and such of the farmers as might drop in. In this way I got much valuable information in relation to farm matters, which would have saved me much trouble and considerable loss if I had known it before. Everybody was interested in my brood-mare and the expected colt, and I talked horse for hours. While I was sitting thus the second evening, I was called to the telephone, and responded with alacrity, for I felt that news of the colt's arrival had come. Sure enough, I recognized my daughter's voice. "Hullo, papa." "Hullo, little girl." "Oh, papa, what do you guess? Lady M. has got a colt. This afternoon I went out, and there was a colt in the pen. Ain't you s'prised?" "Well, well, I'm glad of it, I should say I was surprised." "Grandpa and Mr. Gilman's man are taking care of it. Oh, it has got the longest legs!" "What does Daniel say about it?" "Oh, he said it was the most perfect one he ever saw. He told me to tell you it was the most perfect specimen he ever saw." "Are you all well?" "Yes, and we want you to come home just as soon as you can. Oh, papa, I went right up and patted it." "Well, good-by." "Good-by." Every one about the hotel congratulated me, and the next day, after finishing the case, to which I'm afraid I could not give my undivided attention, I started for home directly after lunch, having notified my family that I would be at home at about four o'clock. My arrival had evidently been not entirely unexpected by persons not connected with my family, for when I drove into the yard I found quite a crowd awaiting me and smiling delightedly at my return. There was my venerable father, Daniel, and his wife, the Professor and his wife, my own family, and several other neighbors, to greet me and shower congratulations upon me. It was the first time that a colt of unblemished ancestry had been foaled in that neighborhood, and it was delightful to witness the genuine appreciation of our friends. I really felt as if I were the chosen instrument to lead them to material improvement in the most important branch of farm-life. And so, escorted by my friends, I walked triumphantly toward the paddock, trying hard not to show too openly the pride and elation I felt, and listening to the heartfelt encomiums of my friends. "Well," said our friend Daniel enthusiastically, "I have bred horses all my life, and I am bound to say it is one of the most perfect types I have yet seen. And when a colt shows its characteristics so young, you may be sure that they are going to stay with it during life." I beamed with pride. "Was there ever a truer saying than 'blood will tell,' Daniel?" asked my venerable father. "Never, George," replied Daniel. "See how strongly the remarkable qualities of his sire appear in the colt. Why Lady M., good animal that she is, is not in the same class with the colt." I beamed some more. "Don't you think," queried the Professor, "that the colt may have inherited some of its remarkable qualities from the first dam of Electric Jim, Sukey M. (2.21)?" "Or from the second dam, Wilkes Jane (2.12 1/2)?" suggested another neighbor. "We all know that the Wilkes blood is highly thought, of among horse-breeders." As he said this I came to the paddock, and my friends drew apart from me in order to let me feast my eyes on the colt. I looked and looked again, and leaned my hands on the fence and stared foolishly. For a moment I could scarcely believe my eyes, for there stood Lady M., her great soft eyes full of love, nuzzling, by all the gods, a long-legged, round-barreled, big-headed mule colt, with the most grotesquely enormous ears I had ever seen. Shades of Balaam and Don Quixote! it looked like a jack-rabbit on stilts. I swallowed hastily, looked for a place to sit down, grinned foolishly, and turned to see my friends in various conditions of convulsions. Daniel was shaking like a huge tumbler of jelly; the Professor was leaning over the fence, holding himself with both hands; my daughter was dancing a grotesque jig; my son was rolling on the ground; while the rest of the assemblage were bending and twisting and cackling like lunatics. Well, I have faced financial crises with coolness, ridiculous situations with dignity, and reverses with resignation, but I never was so completely "graveled" in my life. I do not know what the result would have been, — whether I should have brained the shrieking maniacs, or the mule and its fool dam, or fled from the place, — but just then the sight of that mare nursing that infernal jack-rabbit struck my sense of the ridiculous, and I became the loudest and most abandoned of the shrieking crew. When I had in a measure recovered, I invited all hands to the house, and set out whatever I could find as our first libation to the god of treats. What

that mule cost me since I scarcely dare estimate.  It looked like a jack-rabbit on stilts

|