| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

I

LANDSCAPE GARDENING IT is safe to assert that no other country

has such a

distinctive form of landscape gardening as Japan. In English, French,

Italian,

and Dutch gardens, however original in their way, there are certain

things they

seem all to possess in common: terraces, which originally belonged to

Italian

gardens, were soon introduced into France; clipped trees, which were a

distinctive feature of Dutch gardens, were copied by the English; the

fashion

of decorating gardens with flights of stone steps, balustrades,

fountains, and

statues at one time spread from Italy throughout Europe; and possibly

the

over-decoration of gardens led to a change in taste in England and a

return to

a more natural style. The gardens of China and Japan have remained

unique; the

Eastern style of gardening has never spread to any other country, nor is it ever likely to;

for, just as

no Western artist will ever paint in the same manner as an Oriental

artist

because his whole artistic sense is different, so no Western gardener

could

ever hope to construct a garden

representing a portion of the natural scenery of

Japan — which

is the aim and object of every good Japanese landscape

garden, however small —

because, however long he might study the

original scene, he would never arrive at the Japanese conception of it,

or realise

what it conveyed to the mind of a Japanese. Their art of gardening was

originally borrowed from the Chinese, who appear to have been the first

to

construct miniature mountains, and to bring water from a distance to

feed

miniature water-falls and mountain torrents. They even went so far as,

in one

enclosure, to represent separate scenes for different seasons of the

year, and

different hours of the day, but to the Japanese belongs the honour of

having

perfected the art of landscape gardening. It is not my intention to weary the reader

with

technical information on the subject, which he will find admirably

explained in

Mr. Conder's volume on Landscape Gardening in Japan, but an outline of some

of the theories and rules which guide the Japanese gardener will help us to

appreciate his

work and give an additional interest to the hours spent in these

refreshing

retreats from the outer world. The designer of a good

landscape garden has to be guided by many things. A scene must be

chosen suited

to the size of the ground and the house, and its natural surroundings;

and the

Japanese garden being above all a spot for secluded leisure and meditation,

the temperament,

sentiment, and even the occupation of the owner are brought into

consideration.

Their conception of the expression of nature is governed in its

execution by

endless ęsthetic rules; considerations of scale, proportion, unity, and

balance, in fact all that tends to artistic harmony, must be

considered, so as

to preserve the perfect balance of the picture, and any neglect would destroy that

feeling of repose which is so essential in the landscape garden. When

we

realise that the art has occupied the minds of poets, sages, and

philosophers,

it is not to be wondered at that something more than the simple

representation

of natural views has entered into the spirit of their schemes, which

attain to

poetical conceptions; and a garden may be designed to suggest definite

ideas

and associations, in fact the

whole art

is enshrouded by quaint esthetic principles, and it is difficult for

the

Western mind to unravel the endless laws and theories by which it is

governed.  Wistaria in a Kyoto Garden In gardens which cover a larger area the scheme must necessarily be

very

different from that required for the making of a tiny

garden, only some

few yards square, but the

materials used will be the same; only the stone bridges and garden

ornaments

will all be in proportion to the size of the garden, for the rule of

proportion

is perhaps the most important of all. I visited a garden which was

being

enlarged by the addition of a hill and the suggestion of mountain

forests, to

give the impression of unknown limits. The owner explained that as he

had

enlarged his house it was therefore necessary at the same time to

enlarge his garden.

A landscape garden may be of any size, from the miniature scenes,

representing

pigmy groves, and mossy precipices, with lilliputian torrents of white

sand,

compressed into the area of a china dish, to the vast gardens with

their broad

sheets of water and majestic trees which surrounded the Daimyo castles

of old

or the Imperial palaces of to-day; but the sense of true proportion

must be

rigidly adhered to. Large rocks and boulders are out of place in a

small

garden, and small stones in a large garden would be equally unsuitable.

The

teachers of the craft have been most careful to preserve the purity of

style.

Over-decoration is condemned as vulgar ostentation, and faulty designs

have

even been regarded as unlucky, in order to avoid degeneration in the

art. In some of the most extensive gardens it

is not

uncommon to represent several favourite views, and yet the composition

will be

so contrived that all the separate scenes work into one harmonious

whole. In

the immediate foreground of a nobleman's house there will be an

elaborately

finished garden full of detail and carefully composed, the stones

employed will

be the choicest, the water-basin of quaint and beautiful design. Stone

lanterns

in keeping with the scene will be found, miniature pagodas possibly,

and a few

slabs of some precious stone to form the bridges. Farther away from the

house

the scheme should be less finished. Surrounding the simple room set

apart for

the tea ceremony the law forbids the garden to be finished in style, it

must be rather rough and sketchy, and then if some

natural

wild scene is represented, a broad effect must

be retained; a simple clump of pines or cryptomerias

near a little garden shrine will represent some favourite

temple, or a

small grove of maples and cherry-trees by the side of a stream of

running water

will suggest the scenery of Arashiyama or some other romantic and

poetical

spot. To our Western ideas it seems impossible

that a garden

without flowers could be a thing of beauty, or give any pleasure to its

owner.

Yet, strange as it may appear, flowers for their own sakes do not enter

into

the scheme of Japanese gardening, and if any blossoms are to be found,

it is

probably, so to speak, by accident, because the particular shrub or

plant which

may happen to be in flower was the one best suited by its growth for

the

position it occupies in the garden. For instance, azaleas are often

seen

covering the banks with gorgeous masses of colour, but they are only

allowed,

either on account of their picturesque growth and the fact that they

are

included in the natural vegetation of the scene produced, or else

because the

bushes can be cut into regulation shapes, which, as often as not, is

done when

the flowers are just opening. Though the Japanese are great lovers of

flowers,

their taste is so governed by rules, that they are extremely fastidious

in

their choice of the blossoms they consider worthy of admiration. The

rose and

the lily are rejected as unworthy, their charms are too obvious: their

favourites are the iris, peony, wistaria, lotus, morning glory, and

chrysanthemum; and even among these the iris, wistaria, and possibly

the lotus,

are the only ones which seem ever to be allowed to belong in any way to

the

real design of the garden. Flowering trees take more part, and the

plum, peach,

cherry, magnolia, and camellia are all permitted; and the numerous

fancy

varieties of the maple, whose leaves enrich the autumn landscape with

their

scarlet glory, are as much prized as any of the blossoming shrubs. It

is rather

to the storm-bent old pine-trees and other evergreen trees and shrubs,

to the

mossy lichen-covered stones, to the clever manipulation of the water to

represent a miniature mountain cascade or a flowing river, and to broad

stretches of velvety moss that the true Japanese garden owes its beauty. Mr. Conder tells us that the earliest

style of

gardening in the country was called the Imperial Audience Hall

Style, because,

not unnaturally, it was round the palaces and houses of the great

nobles that

the idea was first adopted of arranging the ground to suggest a real

landscape.

The designs appear to have been primitive, but they usually contained a

large

irregular lake, with at least one island reached by a bridge of

picturesque

form. Later — from

the middle of the twelfth to the beginning of the fourteenth

century — the

art of gardening was much practised and encouraged by the

Buddhist priests. They even went so far as to ascribe imaginary

religious and

moral attributes to the grouping of the stones, a custom which has more

or less

survived to this day and is described elsewhere. In those days a lake

came to

be regarded as a necessary feature, and poetical names were given to

the little

islets, just as the pine-clad islands of Matsu-shima have each their

poetical

name. Cascades also received names according to their character, such

as the

"Thread Fall," the "Spouting Fall," or the "Side

Fall." In the making of a garden then, as to-day, the first work was

the

excavation of the lake, the designing and forming of the islands, the

placing

in position of a few of the most important stones, and finally the

arrangement

of the waterfall or stream which was to feed the lake, and the outlet

had also

to be carefully considered. After this period came the fashion of

representing

lakes and rivers by means of hollowed-out beds and courses, merely

strewn with

sand, pebbles, and boulders, a practice followed also to this day where

water

is not available. Shallow water or dried-up river-beds are suggested in

this

way, and therefore the style received the name of Dried-up Water

Scenery. Artificial

hills were used, stones and winding pathways were introduced, and large

rocks

helped to suggest natural scenery. It was in the fifteenth century that the

art of

gardening received the greatest encouragement and attention at the

hands of the

Ashikaya Regents, who also encouraged the other arts of flower

arrangement —

tea ceremony and poetry. The Professors of Cha no yu (tea ceremony)

became the principal designers of gardens, and they naturally turned

their

attention to the ground which surrounded the rooms set apart for this

ceremonial tea-drinking; and to the famous Soami, who was a Professor

of

Tea-ceremonial and the Floral Art, they owe the practice of clipping

trees and

shrubs into fantastic shapes. Though the Japanese never attained to the

unnatural eccentricities of the Dutch in their manner of using clipped

trees,

yet in many old and modern gardens a pine-tree may be seen clipped and

trained

in the shape of a junk, and a juniper may be trained to form a light

bridge to

fling across a tiny stream; but as a rule the gardener contents himself

by

training and clipping his pine-tree to mould it into the shape of an

abnormal

storm-bent specimen of great age. To that period belonged Kobori

Enshiu, the designer

of so many celebrated gardens, and to him we owe the garden of the

Katsura

Rikui, a detached Palace near Kyoto, which, though fallen into decay,

retains

much of its former beauty, especially when the scarlet azalea bushes,

which now

escape the clipping they no doubt were subjected to in old days, light

up the

scene, their lichen-clad stems bending under the weight of their

blossoms and

enhancing the beauty of the moss-grown lanterns and stones. The garden

which

surrounded the temple of Kodaiji, a portion only of the grounds of the

old

palace of Awata, the Konchi-in garden of the Nanzenji Temple, and many

other

specimens of his work remain in Kyoto alone. He is reported to have

said that

his ideal garden should express "the sweet solitude of a landscape

clouded

by moonlight, with a half gloom between the trees." Rikiu, another

great

tea professor and designer of landscape gardens, said the best

conception of

his fancy would be that of the "lonely precincts of a secluded mountain

shrine, with the red leaves of autumn scattered around." However

different

their ideal, they all agreed that the tea garden was to be somewhat

wild in

character, suggesting repose and solitude. Then came the more modem

style of

gardening: from

1789 to 1880 was a period when

large

palaces were built and surrounded by magnificent gardens, fit

residences for

the great Tokugawa feudal lords. For these gardens great sums were

expended on

collecting stones from all parts of the country, and often a garden

would be

left unfinished until the exact stone suited to express the required

religious

or poetical feeling, or else specially required to complete a miniature

natural

scene, had been procured. The extravagance in this craving for rare stones, which cost vast sums to transport immense

distances,

reached such a pitch, that at last, in the Tempo period (1830-1844), an edict was issued limiting the sum which

might be paid

for a single specimen. Stone and granite lanterns of infinite variety

in size

and shape were introduced with their poetical names, each having a

special

position assigned to it by the unbending laws which surround this art,

for the

arrangement of not only every tree and stone, but almost every blade of

grass

and drop of water. I feel my readers will begin to think that there

must be a

lack of variety in these landscape gardens, but I can safely say that

never did

I see — and I

saw a great many — any

two gardens, large or small, which bore

any resemblance to each other; the materials are the same, but the

design is

never the same. Garden water-basins, miniature pagodas,

stone

bridges, also of infinite variety, and other garden ornaments, such as

rustic

arbours, fanciful constructions of bamboo, reeds, or plaited rushes,

primitive,

fragile-looking structures, but none the less costly, were made use of,

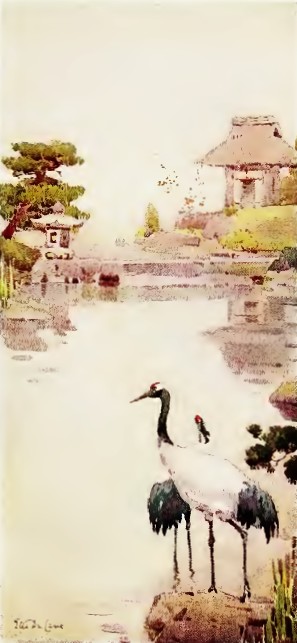

and a

few rare birds, such as storks and cranes, were allowed to wander and

adorn the

scene with their stately grace. Here and there the crooked branches of

stunted

pine-trees of great age overhung the lake or stream, transplanted

probably with

infinite care; but no trouble and no expense was too great to make

these

gardens fitting settings for the castles and palaces of those great

lords.

Alas, how few remain to-day in anything like their former splendour;

the hand

of the Goth has swept away most of the ancient glories of Yedo, and on

the spot

where these princely dwellings and gardens stood, to-day some great

factory

chimneys rise and belch forth columns

of smoke, which will surely

bring death and destruction to the pines and cherry-trees of Uyeno or

the

avenues of Mukojima, which are still the pride of Tokyo.  The Storks Tokyo may still retain the remains of some

of her

princely gardens, but I fear she has lost her love of gardening; the

town is

too large, too crowded; the rich who could afford to make new gardens,

even if

the old ones are swept away, prefer to live in foreign houses of

impossible

architectural design; the public gardens are no longer laid out in true

Japanese style, but suggestive rather of foreign gardens of the worst

form and

taste, so if you would see the making of a new garden it is to Kyoto

you must

wend your way. Here the love of landscape gardening seems still alive,

and

though the gardens may not surround the palaces of the Daimyos, yet

these humbler

gardens which as often as not surround the house of a rich Osaka

tradesman are

none the less beautiful for that reason; and I was glad to think that

riches

had not, as is too often the case, brought with it a love for foreign

life and

stamped out the true Japanese, and that here at least are left many who

are

content to spend their hours of leisure in the contemplation and in the

repose

of a true landscape garden. In the course of an evening walk on the

outskirts of

Kyoto I came upon a half-built house. Through the newly planted

cryptomeria

hedge could be seen glimpses of stone lanterns, rocks, and a few trees

kept in

place by bamboo props, while in the road outside lay stones of all

colours,

shapes, and sizes. Garden coolies were passing in and out, carrying

baskets of

earth slung on bamboo poles, so it was evident that a garden was being

made. My

curiosity was aroused, so I ventured within the enclosure, and, in the

most

polite language I could command, asked permission of the owner to watch

the

interesting work. A Japanese is always gratified by the genuine

interest of a

foreigner in anything connected with his home, and will usually point

out the

special features of the object of interest in eloquent and poetical

phrases,

confusing enough to the foreigner, whose command of the Japanese

language

cannot as a rule rise to such heights. On this occasion, however, any

explanation was unnecessary, the scene in itself was sufficient to call

forth

my admiration and surprise. The piece of ground occupied by the garden

did not

comprise more than half an acre, and was merely the plot usually

attached to

any suburban villa in England. Notwithstanding the limited space, a

perfect

landscape was growing out of the chaos of waste ground which had been

chosen as

the site of the house. A miniature lake of irregular shape had been dug

out; an

island consisting of just one bold rock, to be christened no doubt in

due time

with some fanciful name, had been placed in position; and there were

the

"Guardian Stone," always the most important stone in the near

distance, and its associates the "Stone of Worship"

— also sometimes called the

"Stone of Contemplation," as from

this stone the best general view of the garden is obtained

— and the "Stone of the Two

Deities." The presence of these

three stones being essential in the composition of every garden, they

are

probably the first to be placed. A few trees of venerable appearance

had

already been planted in the orthodox places; and already one spreading

pine-tree stretched across the future lake, supported on an elaborate

framework

of bamboo, to give it exactly the right shape and direction; near to

it, and

resting on a slab of rock at the very edge of the water, was a stone

lantern of

the "Snow Scene" shape; the two forming the principal features of the garden, upon which the eye rested

involuntarily. Another stone lantern stood in the shadow of a tall and

twisted

pine, half buried in low-growing shrubs, bedded in moss of a

golden-brown

colour. On one side was a bank thickly planted with azaleas, groups of

maples,

or camellias, and at the far end of the garden some tall evergreen

trees

cleverly disguised the boundary line of the hedge and gave the

impression that

the garden had no ending, save in the wooded hills that shut in the

surrounding

valley. A cutting in the bank and a wonderfully natural arrangement of

"Cascade Stones" showed where the water would eventually rush in from

the stream outside, which had its source in Lake Biwa. A path of beaten

earth

with stepping-stones embedded in it wound round the little lake and

through the

grove at the side; a simple bridge of mere slabs of stone crossed the

water to

where the pathway ended in the inevitable tea-room. Many more lanterns,

pagodas, and other garden ornaments lay on the ground waiting for their

allotted place, while a whole nursery of trees carefully laid in loose

earth

showed that much more planting was needed to complete the garden, which

would

some day be the pride and delight of the owner's heart. The whole country is often searched for a tree of exactly the right size and shape required for a particular position, and while watching the work of making this new garden I was much struck by the extraordinary skill the Japanese display in the transplanting of trees of almost any size and age. The season chosen for their removal is the spring, when the sap is rising, and the dampness of the climate and the rich soil no doubt help considerably towards their success in moving these old trees; unlike England, spring is their best season for planting, as the trees will have all the benefit of the summer rains and run no risk of drought or cold winds. The roots are trenched round, to our idea, perilously near the tree; as much earth is retained as possible and bound round with matting. Five or six coolies with a length of rope, a few poles, and not a little ingenuity, will move the largest tree in a very short time. There is no machinery or fuss of any kind, merely a handbarrow, on which the tree rests on its journey. Very little preparation is made in the place where the tree is to be planted; no trenching of the ground, or preparing of vast holes to be filled with prepared soil, only a hole just large enough for the ball of earth surrounding the roots is considered sufficient. The tree is then put in place, upright or leaning, according to the effect required, the soil tightly rammed round the roots, the necessary pruning and propping carefully attended to; the ground artistically planted with moss and made to look as if it had never been disturbed for centuries, and the thing is done. I remember seeing a piece of ground which was being prepared for building, on which were a few plum-trees of considerable size and age; these were being carefully removed, doubtless to give a venerable appearance to some new garden, or to be planted in a nursery garden until they should be wanted elsewhere, — surely a better fate than would have awaited them in our country under similar circumstances, where the devastating axe of the builder's labourer would certainly have cleared the ground in a few minutes of what he would have regarded as useless rubbish. |