| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

(HOME)

|

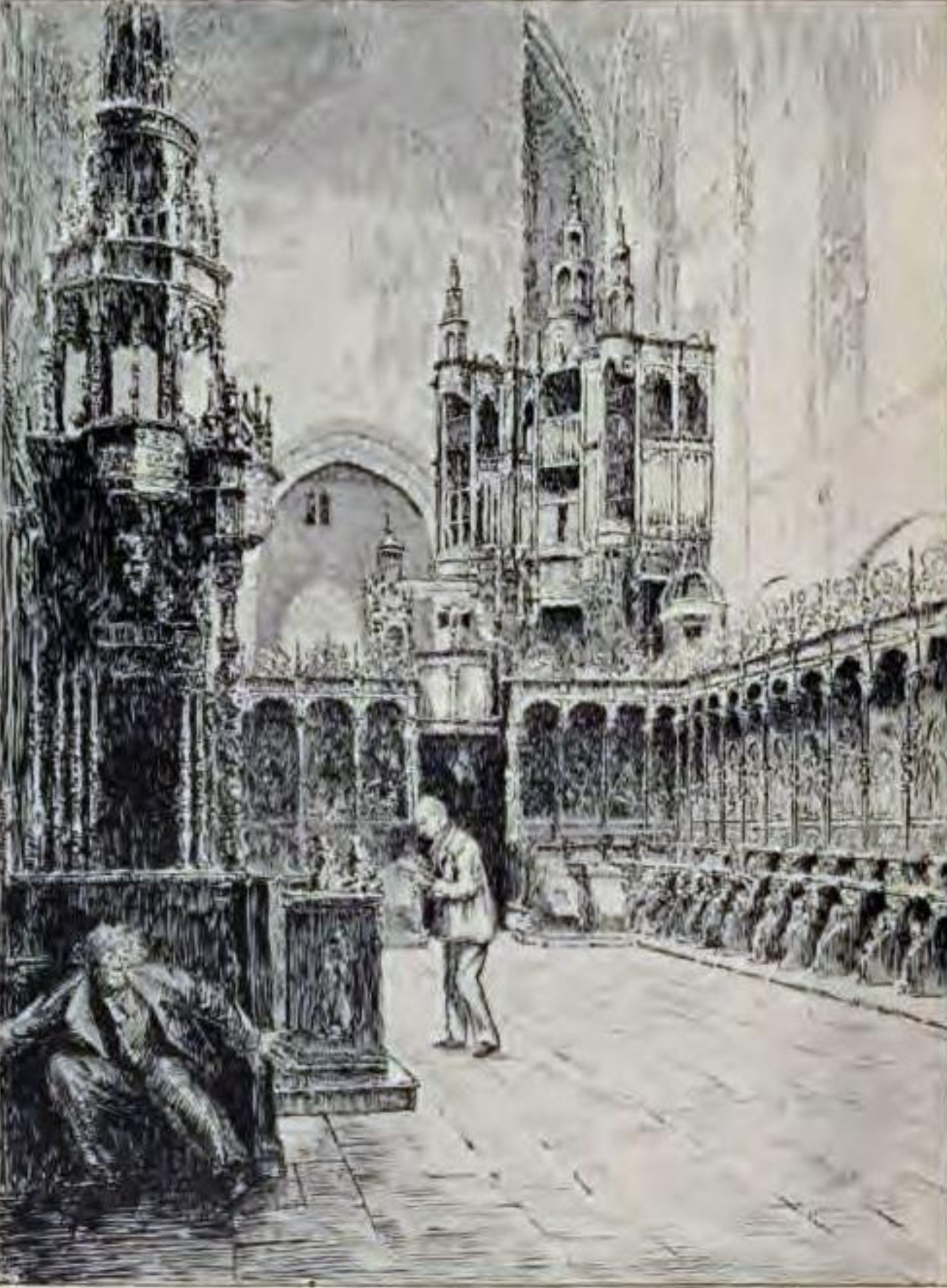

| Canon Alberic’s

Scrap-Book

St Bertrand de

Comminges is a decayed town on the spurs of the

Pyrenees, not very far from Toulouse, and still nearer to

Bagnères-deLuchon. It

was the site of a bishopric until the Revolution, and has a cathedral

which is

visited by a certain number of tourists. In the spring of 1883 an

Englishman

arrived at this old-world place — I can hardly dignify it with the name

of

city, for there are not a thousand inhabitants. He was a Cambridge man,

who had

come specially from Toulouse to see St Bertrand’s Church, and had left

two

friends, who were less keen archaeologists than himself, in their hotel

at

Toulouse, under promise to join him on the following morning. Half an

hour at

the church would satisfy them, and all three could then pursue

their

journey in the direction of Auch. But our Englishman had come early on

the day

in question, and proposed to himself to fill a note-book and to use

several

dozens of plates in the process of describing and photographing every

corner of

the wonderful church that dominates the little hill of Comminges. In

order to

carry out this design satisfactorily, it was necessary to monopolize

the verger

of the church for the day. The verger or sacristan (I prefer the latter

appellation, inaccurate as it may be) was accordingly sent for by the

somewhat

brusque lady who keeps the inn of the Chapeau Rouge; and when he came,

the

Englishman found him an unexpectedly interesting object of study. It

was not in

the personal appearance of the little, dry, wizened old man that the

interest

lay, for he was precisely like dozens of other church-guardians in

France, but

in a curious furtive or rather hunted and oppressed air which he had.

He was

perpetually half glancing behind him; the muscles of his back and

shoulders

seemed to be hunched in a continual nervous contraction, as if he were

expecting every moment to find himself in the clutch of an enemy. The

Englishman hardly knew whether to put him down as a man haunted by a

fixed

delusion, or as one oppressed by a guilty conscience, or as an

unbearably

henpecked husband. The probabilities, when reckoned up, certainly

pointed to

the last idea; but, still, the impression conveyed was that of a more

formidable persecutor even than a termagant wife.

However, the

Englishman (let us call him Dennistoun) was soon too deep

in his note-book and too busy with his camera to give more than an

occasional

glance to the sacristan. Whenever he did look at him, he found him at

no great

distance, either huddling himself back against the wall or crouching in

one of

the gorgeous stalls. Dennistoun became rather fidgety after a time.

Mingled

suspicions that he was keeping the old man from his déjeuner,

that he

was regarded as likely to make away with St Bertrand’s ivory crozier,

or with

the dusty stuffed crocodile that hangs over the font, began to torment

him. ‘Won’t you go home?’

he said at last; ‘I’m quite well able to finish my

notes alone; you can lock me in if you like. I shall want at least two

hours

more here, and it must be cold for you, isn’t it?’ ‘Good heavens!’ said

the little man, whom the suggestion seemed to

throw into a state of unaccountable terror, ‘such a thing cannot be

thought of

for a moment. Leave monsieur alone in the church? No, no; two hours,

three

hours, all will be the same to me. I have breakfasted, I am not at all

cold,

with many thanks to monsieur.’ ‘Very well, my

little man,’ quoth Dennistoun to himself: ‘you have been

warned, and you must take the consequences.’ Before the

expiration of the two hours, the stalls, the enormous

dilapidated organ, the choir-screen of Bishop John de Mauléon, the

remnants of

glass and tapestry, and the objects in the treasure-chamber had been

well and

truly examined; the sacristan still keeping at Dennistoun’s heels, and

every

now and then whipping round as if he had been stung, when one or other

of the

strange noises that trouble a large empty building fell on his ear.

Curious

noises they were, sometimes. ‘Once,’ Dennistoun

said to me, ‘I could have sworn I heard a thin

metallic voice laughing high up in the tower. I darted an inquiring

glance at

my sacristan. He was white to the lips. “It is he — that is — it is no

one; the

door is locked,” was all he said, and we looked at each other for a

full

minute.’ Another little

incident puzzled Dennistoun a good deal. He was

examining a large dark picture that hangs behind the altar, one of a

series

illustrating the miracles of St Bertrand. The composition of the

picture is

well-nigh indecipherable, but there is a Latin legend below, which runs

thus: Qualiter S. Bertrandus liberavit hominem quem diabolus diu volebat strangulare. (How St Bertrand delivered a man whom the Devil long sought to strangle.) It was nearly five

o’clock; the short day was drawing in, and the

church began to fill with shadows, while the curious noises — the

muffled

footfalls and distant talking voices that had been perceptible all day

—

seemed, no doubt because of the fading light and the consequently

quickened

sense of hearing, to become more frequent and insistent. The sacristan began

for the first time to show signs of hurry and

impatience. He heaved a sigh of relief when camera and note-book were

finally

packed up and stowed away, and hurriedly beckoned Dennistoun to the

western

door of the church, under the tower. It was time to ring the Angelus. A

few

pulls at the reluctant rope, and the great bell Bertrande, high in the

tower,

began to speak, and swung her voice up among the pines and down to the

valleys,

loud with mountain-streams, calling the dwellers on those lonely hills

to remember

and repeat the salutation of the angel to her whom he called Blessed

among

women. With that a profound quiet seemed to fall for the first time

that day

upon the little town, and Dennistoun and the sacristan went out of the

church. On the doorstep they

fell into conversation. ‘Monsieur seemed to

interest himself in the old choir-books in the

sacristy.’ ‘Undoubtedly. I was

going to ask you if there were a library in the

town.’ ‘No, monsieur;

perhaps there used to be one belonging to the Chapter,

but it is now such a small place —’ Here came a strange pause of

irresolution,

as it seemed; then, with a sort of plunge, he went on: ‘But if monsieur

is amateur

des vieux livres, I have at home something that might interest him.

It is

not a hundred yards.’ At once all

Dennistoun’s cherished dreams of finding priceless

manuscripts in untrodden corners of France flashed up, to die down

again the

next moment. It was probably a stupid missal of Plantin’s printing,

about 1580.

Where was the likelihood that a place so near Toulouse would not have

been

ransacked long ago by collectors? However, it would be foolish not to

go; he

would reproach himself for ever after if he refused. So they set off.

On the

way the curious irresolution and sudden determination of the sacristan

recurred

to Dennistoun, and he wondered in a shamefaced way whether he was being

decoyed

into some purlieu to be made away with as a supposed rich Englishman.

He

contrived, therefore, to begin talking with his guide, and to drag in,

in a

rather clumsy fashion, the fact that he expected two friends to join

him early

the next morning. To his surprise, the announcement seemed to relieve

the

sacristan at once of some of the anxiety that oppressed him. ‘That is well,’ he

said quite brightly —‘that is very well. Monsieur

will travel in company with his friends: they will be always near him.

It is a

good thing to travel thus in company — sometimes.’ The last word

appeared to be added as an afterthought and to bring with

it a relapse into gloom for the poor little man. They were soon at

the house, which was one rather larger than its

neighbours, stone-built, with a shield carved over the door, the shield

of

Alberic de Mauléon, a collateral descendant, Dennistoun tells me, of

Bishop

John de Mauléon. This Alberic was a Canon of Comminges from 1680 to

1701. The

upper windows of the mansion were boarded up, and the whole place bore,

as does

the rest of Comminges, the aspect of decaying age. Arrived on his

doorstep, the sacristan paused a moment. ‘Perhaps,’ he said,

‘perhaps, after all, monsieur has not the time?’ ‘Not at all — lots

of time — nothing to do till tomorrow. Let us see

what it is you have got.’ The door was opened

at this point, and a face looked out, a face far

younger than the sacristan’s, but bearing something of the same

distressing

look: only here it seemed to be the mark, not so much of fear for

personal

safety as of acute anxiety on behalf of another. Plainly the owner of

the face

was the sacristan’s daughter; and, but for the expression I have

described, she

was a handsome girl enough. She brightened up considerably on seeing

her father

accompanied by an able-bodied stranger. A few remarks passed between

father and

daughter of which Dennistoun only caught these words, said by the

sacristan:

‘He was laughing in the church,’ words which were answered only by a

look of

terror from the girl. But in another

minute they were in the sitting-room of the house, a

small, high chamber with a stone floor, full of moving shadows cast by

a

wood-fire that flickered on a great hearth. Something of the character

of an

oratory was imparted to it by a tall crucifix, which reached almost to

the

ceiling on one side; the figure was painted of the natural colours, the

cross

was black. Under this stood a chest of some age and solidity, and when

a lamp

had been brought, and chairs set, the sacristan went to this chest, and

produced therefrom, with growing excitement and nervousness, as

Dennistoun

thought, a large book, wrapped in a white cloth, on which cloth a cross

was

rudely embroidered in red thread. Even before the wrapping had been

removed,

Dennistoun began to be interested by the size and shape of the volume.

‘Too

large for a missal,’ he thought, ‘and not the shape of an antiphoner;

perhaps

it may be something good, after all.’ The next moment the book was

open, and

Dennistoun felt that he had at last lit upon something better than

good. Before

him lay a large folio, bound, perhaps, late in the seventeenth century,

with

the arms of Canon Alberic de Mauléon stamped in gold on the sides.

There may

have been a hundred and fifty leaves of paper in the book, and on

almost every

one of them was fastened a leaf from an illuminated manuscript. Such a

collection Dennistoun had hardly dreamed of in his wildest moments.

Here were

ten leaves from a copy of Genesis, illustrated with pictures, which

could not

be later than A.D. 700. Further on was a complete set of pictures from

a

Psalter, of English execution, of the very finest kind that the

thirteenth

century could produce; and, perhaps best of all, there were twenty

leaves of

uncial writing in Latin, which, as a few words seen here and there told

him at

once, must belong to some very early unknown patristic treatise. Could

it

possibly be a fragment of the copy of Papias ‘On the Words of Our

Lord’, which

was known to have existed as late as the twelfth century at Nimes?1

In any case, his mind was made up; that book must return to Cambridge

with him,

even if he had to draw the whole of his balance from the bank and stay

at St.

Bertrand till the money came. He glanced up at the sacristan to see if

his face

yielded any hint that the book was for sale. The sacristan was pale,

and his

lips were working. ‘If monsieur will

turn on to the end,’ he said. So monsieur turned

on, meeting new treasures at every rise of a leaf;

and at the end of the book he came upon two sheets of paper, of much

more

recent date than anything he had seen yet, which puzzled him

considerably. They

must be contemporary, he decided, with the unprincipled Canon Alberic,

who had doubtless

plundered the Chapter library of St Bertrand to form this priceless

scrap-book.

On the first of the paper sheets was a plan, carefully drawn and

instantly

recognizable by a person who knew the ground, of the south aisle and

cloisters

of St Bertrand’s. There were curious signs looking like planetary

symbols, and

a few Hebrew words in the corners; and in the north-west angle of the

cloister

was a cross drawn in gold paint. Below the plan were some lines of

writing in

Latin, which ran thus: Responsa

12(mi) Dec. 1694. Interrogatum est: Inveniamne? Responsum est: Invenies. Fiamne dives?

Fies. Vivamne invidendus? Vives. Moriarne in lecto meo? Ita. What he then saw

impressed him, as he has often told me, more than he

could have conceived any drawing or picture capable of impressing him.

And,

though the drawing he saw is no longer in existence, there is a

photograph of

it (which I possess) which fully bears out that statement. The picture

in

question was a sepia drawing at the end of the seventeenth century,

representing, one would say at first sight, a Biblical scene; for the

architecture (the picture represented an interior) and the figures had

that

semi-classical flavour about them which the artists of two hundred

years ago

thought appropriate to illustrations of the Bible. On the right was a

king on

his throne, the throne elevated on twelve steps, a canopy overhead,

soldiers on

either side — evidently King Solomon. He was bending forward with

outstretched

sceptre, in attitude of command; his face expressed horror and disgust,

yet

there was in it also the mark of imperious command and confident power.

The

left half of the picture was the strangest, however. The interest

plainly

centred there. On the pavement

before the throne were grouped four soldiers,

surrounding a crouching figure which must be described in a moment. A

fifth

soldier lay dead on the pavement, his neck distorted, and his eye-balls

starting from his head. The four surrounding guards were looking at the

King.

In their faces, the sentiment of horror was intensified; they seemed,

in fact,

only restrained from flight by their implicit trust in their master.

All this

terror was plainly excited by the being that crouched in their midst. I entirely despair

of conveying by any words the impression which this

figure makes upon anyone who looks at it. I recollect once showing the

photograph of the drawing to a lecturer on morphology — a person of, I

was

going to say, abnormally sane and unimaginative habits of mind. He

absolutely

refused to be alone for the rest of that evening, and he told me

afterwards

that for many nights he had not dared to put out his light before going

to

sleep. However, the main traits of the figure I can at least indicate. At first you saw

only a mass of coarse, matted black hair; presently it

was seen that this covered a body of fearful thinness, almost a

skeleton, but

with the muscles standing out like wires. The hands were of a dusky

pallor,

covered, like the body, with long, coarse hairs, and hideously taloned.

The

eyes, touched in with a burning yellow, had intensely black pupils, and

were

fixed upon the throned King with a look of beast-like hate. Imagine one

of the

awful bird-catching spiders of South America translated into human

form, and

endowed with intelligence just less than human, and you will have some

faint

conception of the terror inspired by the appalling effigy. One remark

is

universally made by those to whom I have shown the picture: ‘It was

drawn from

the life.’ As soon as the first

shock of his irresistible fright had subsided,

Dennistoun stole a look at his hosts. The sacristan’s hands were

pressed upon

his eyes; his daughter, looking up at the cross on the wall, was

telling her

beads feverishly. At last the question

was asked: ‘Is this book for sale?’ There was the same

hesitation, the same plunge of determination that he

had noticed before, and then came the welcome answer: ‘If monsieur

pleases.’ ‘How much do you ask

for it?’ ‘I will take two

hundred and fifty francs.’ This was

confounding. Even a collector’s conscience is sometimes

stirred, and Dennistoun’s conscience was tenderer than a collector’s. ‘My good man!’ he

said again and again, ‘your book is worth far more

than two hundred and fifty francs. I assure you — far more.’ But the answer did

not vary: ‘I will take two hundred and fifty francs

— not more.’ There was really no

possibility of refusing such a chance. The money

was paid, the receipt signed, a glass of wine drunk over the

transaction, and

then the sacristan seemed to become a new man. He stood upright, he

ceased to

throw those suspicious glances behind him, he actually laughed or tried

to

laugh. Dennistoun rose to go. ‘I shall have the

honour of accompanying monsieur to his hotel?’ said

the sacristan. ‘Oh, no, thanks! it

isn’t a hundred yards. I know the way perfectly,

and there is a moon.’ The offer was

pressed three or four times and refused as often. ‘Then, monsieur will

summon me if — if he finds occasion; he will keep

the middle of the road, the sides are so rough.’ ‘Certainly,

certainly,’ said Dennistoun, who was impatient to examine

his prize by himself; and he stepped out into the passage with his book

under

his arm. Here he was met by

the daughter; she, it appeared, was anxious to do a

little business on her own account; perhaps, like Gehazi, to ‘take

somewhat’

from the foreigner whom her father had spared. ‘A silver crucifix

and chain for the neck; monsieur would perhaps be

good enough to accept it?’ Well, really,

Dennistoun hadn’t much use for these things. What did

mademoiselle want for it? ‘Nothing — nothing

in the world. Monsieur is more than welcome to it.’ The tone in which

this and much more was said was unmistakably genuine,

so that Dennistoun was reduced to profuse thanks, and submitted to have

the

chain put round his neck. It really seemed as if he had rendered the

father and

daughter some service which they hardly knew how to repay. As he set

off with

his book they stood at the door looking after him, and they were still

looking

when he waved them a last good night from the steps of the Chapeau

Rouge. Dinner was over, and

Dennistoun was in his bedroom, shut up alone with

his acquisition. The landlady had manifested a particular interest in

him since

he had told her that he had paid a visit to the sacristan and bought an

old

book from him. He thought, too, that he had heard a hurried dialogue

between

her and the said sacristan in the passage outside the salle à manger;

some words to the effect that ‘Pierre and Bertrand would be sleeping in

the

house’ had closed the conversation. All this time a

growing feeling of discomfort had been creeping over

him — nervous reaction, perhaps, after the delight of his discovery.

Whatever it

was, it resulted in a conviction that there was someone behind him, and

that he

was far more comfortable with his back to the wall. All this, of

course,

weighed light in the balance as against the obvious value of the

collection he

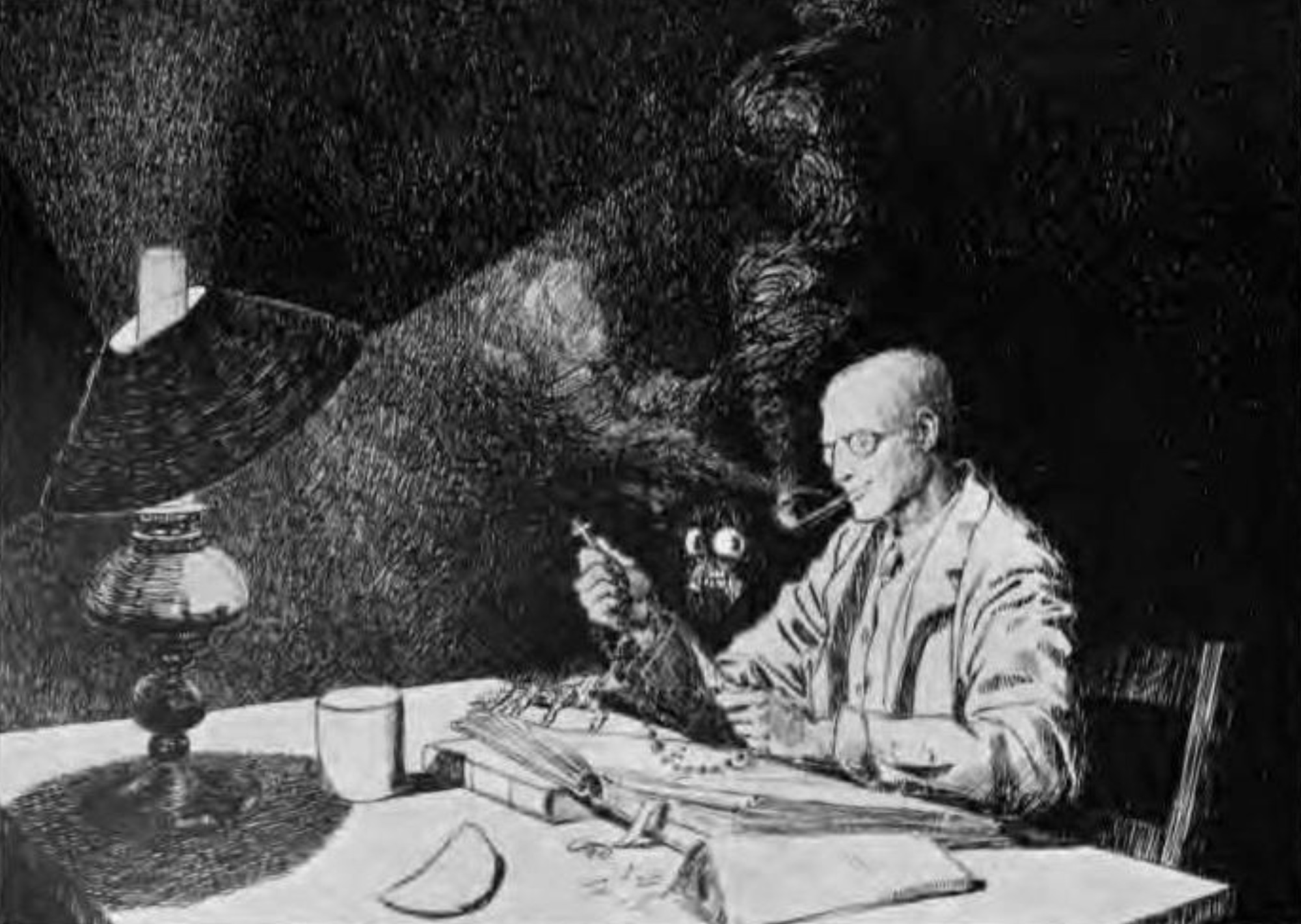

had acquired. And now, as I said, he was alone in his bedroom, taking

stock of

Canon Alberic’s treasures, in which every moment revealed something

more

charming. ‘Bless Canon

Alberic!’ said Dennistoun, who had an inveterate habit of

talking to himself. ‘I wonder where he is now? Dear me! I wish that

landlady

would learn to laugh in a more cheering manner; it makes one feel as if

there

was someone dead in the house. Half a pipe more, did you say? I think

perhaps

you are right. I wonder what that crucifix is that the young woman

insisted on

giving me? Last century, I suppose. Yes, probably. It is rather a

nuisance of a

thing to have round one’s neck — just too heavy. Most likely her father

has

been wearing it for years. I think I might give it a clean up before I

put it

away.’ He had taken the crucifix off, and laid it on the table, when his attention was caught by an object lying on the red cloth just by his left elbow. Two or three ideas of what it might be flitted through his brain with their own incalculable quickness. A penwiper? No, no such thing in the house. A rat? No, too black. A large spider? I trust to goodness not — no. Good God! a hand like the hand in that picture!  A hand like the hand in that picture He flew out of his

chair with deadly, inconceivable terror clutching at

his heart. The shape, whose left hand rested on the table, was rising

to a

standing posture behind his seat, its right hand crooked above his

scalp. There

was black and tattered drapery about it; the coarse hair covered it as

in the

drawing. The lower jaw was thin — what can I call it? — shallow, like a

beast’s; teeth showed behind the black lips; there was no nose; the

eyes, of a

fiery yellow, against which the pupils showed black and intense, and

the exulting

hate and thirst to destroy life which shone there, were the most

horrifying

features in the whole vision. There was intelligence of a kind in them

—

intelligence beyond that of a beast, below that of a man. The feelings which

this horror stirred in Dennistoun were the intensest

physical fear and the most profound mental loathing. What did he do?

What could

he do? He has never been quite certain what words he said, but he knows

that he

spoke, that he grasped blindly at the silver crucifix, that he was

conscious of

a movement towards him on the part of the demon, and that he screamed

with the

voice of an animal in hideous pain. Pierre and Bertrand,

the two sturdy little serving-men, who rushed in,

saw nothing, but felt themselves thrust aside by something that passed

out

between them, and found Dennistoun in a swoon. They sat up with him

that night,

and his two friends were at St Bertrand by nine o’clock next morning.

He

himself, though still shaken and nervous, was almost himself by that

time, and

his story found credence with them, though not until they had seen the

drawing

and talked with the sacristan. Almost at dawn the

little man had come to the inn on some pretence, and

had listened with the deepest interest to the story retailed by the

landlady.

He showed no surprise. ‘It is he — it is

he! I have seen him myself,’ was his only comment;

and to all questionings but one reply was vouchsafed: ‘Deux fois je

l’ai vu:

mille fois je l’ai senti.’ He would tell them nothing of the provenance

of the

book, nor any details of his experiences. ‘I shall soon sleep, and my

rest will

be sweet. Why should you trouble me?’ he said.2 We shall never know

what he or Canon Alberic de Mauléon suffered. At

the back of that fateful drawing were some lines of writing which may

be

supposed to throw light on the situation:

Sancte

Bertrande,

demoniorum effugator, intercede pro me miserrimo. Primum

uidi nocte

12(mi) Dec. 1694: Dec.

29, 1701.3 Another confidence

of his impressed me rather, and I sympathized with

it. We had been, last year, to Comminges, to see Canon Alberic’s tomb.

It is a

great marble erection with an effigy of the Canon in a large wig and

soutane,

and an elaborate eulogy of his learning below. I saw Dennistoun talking

for

some time with the Vicar of St Bertrand’s, and as we drove away he said

to me:

‘I hope it isn’t wrong: you know I am a Presbyterian — but I— I believe

there

will be “saying of Mass and singing of dirges” for Alberic de Mauléon’s

rest.’

Then he added, with a touch of the Northern British in his tone, ‘I had

no

notion they came so dear.’ The book is in the

Wentworth Collection at Cambridge. The drawing was

photographed and then burnt by Dennistoun on the day when he left

Comminges on

the occasion of his first visit. 1 We now know that these leaves did contain a considerable

fragment of

that work, if not of that actual copy of it. 2 He died that summer; his daughter married, and settled at St

Papoul.

She never understood the circumstances of her father’s ‘obsession’. 3 i.e., The Dispute of

Solomon with a demon of the night. Drawn by Alberic de

Mauléon. Versicle. O Lord, make haste to help me. Psalm.

Whoso

dwelleth xci. I saw it first on

the night of Dec. 12, 1694: soon I shall see it for

the last time. I have sinned and suffered, and have more to suffer yet. Dec. 29, 1701. The ‘Gallia

Christiana’ gives the date of the Canon’s death as December

31, 1701, ‘in bed, of a sudden seizure’. Details of this kind are not

common in

the great work of the Sammarthani. |