| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2013 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

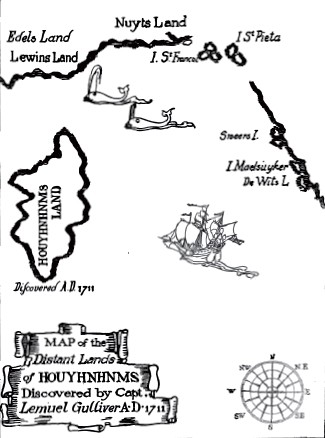

TRAVELS INTO SEVERAL REMOTE NATIONS OF

THE WORLD  PART IV  A Voyage to the Houyhnhnms  CHAPTER I The Author sets out as Captain of a ship. His men conspire against him, confine him a long time to his cabin, set him on shore in an unknown land. He travels up into the country. The Yahoos, a strange sort of animal, described. The Author meets two Houyhnhnms.

I CONTINUED at home with my wife and children about five months in a very happy condition, if I could have learned the lesson of knowing when I was well. I accepted an advantageous offer made me to be Captain of the Adventurer, a stout merchantman of 350 tons: for I understood navigation well, and being grown weary of a surgeon's employment at sea, which however I could exercise upon occasion, I took a skilful young man of that calling, one Robert Purefoy, into my ship. We set sail from Portsmouth upon the seventh day of September, 1710; on the fourteenth we met with Captain Pocock of Bristol, at Teneriffe, who was going to the bay of Campechy, to cut logwood. On the sixteenth, he was parted from us by a storm; I heard since my return, that his ship foundered, and none escaped but one cabin boy. He was an honest man, and a good sailor, but a little too positive in his own opinions, which was the cause of his destruction, as it hath been of several others. For if he had followed my advice, he might have been safe at home with his family at this time, as well as myself. I had several men died in my ship of calentures, so that I was forced to get recruits out of Barbadoes, and the Leeward Islands, where I touched by the direction of the merchants who employed me, which I had soon too much cause to repent: for I found afterwards that most of them had been buccaneers. I had fifty hands on board, and my orders were, that I should trade with the Indians in the South-Sea, and make what discoveries I could. These rogues whom I had picked up debauched my other men, and they all formed a conspiracy to seize the ship and secure me; which they did one morning, rushing into my cabin, and binding me hand and foot, threatening to throw me overboard, if I offered to stir. I told them, I was their prisoner, and would submit. This they made me swear to do, and then they unbound me, only fastening one of my legs with a chain near my bed, and placed a sentry at my door with his piece charged, who was commanded to shoot me dead, if I attempted my liberty. They sent me down victuals and drink, and took the government of the ship to themselves. Their design was to turn pirates, and plunder the Spaniards, which they could not do, till they got more men. But first they resolved to sell the goods in the ship, and then go to Madagascar for recruits, several among them having died since my confinement. They sailed many weeks, and traded with the Indians, but I knew not what course they took, being kept a close prisoner in my cabin, and expecting nothing less than to be murdered, as they often threatened me. Upon the ninth day of May, 1711, one James Welch came down to my cabin; and said he had orders from the Captain to set me ashore. I expostulated with him, but in vain; neither would he so much as tell me who their new Captain was. They forced me into the long-boat, letting me put on my best suit of clothes, which were as good as new, and a small bundle of linen, but no arms except my hanger; and they were so civil as not to search my pockets, into which I conveyed what money I had, with some other little necessaries. They rowed about a league, and then set me down on a strand. I desired them to tell me what country it was. They all swore, they knew no more than myself, but said, that the Captain (as they called him) was resolved, after they had sold the lading, to get rid of me in the first place where they could discover land. They pushed off immediately, advising me to make haste, for fear of being overtaken by the tide, and so bade me farewell. In

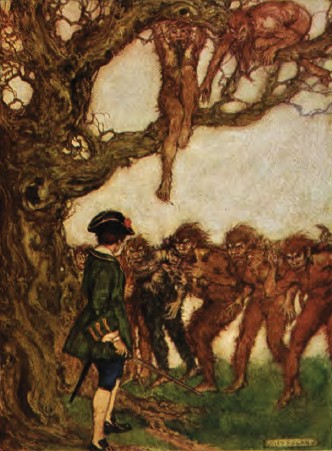

this desolate condition I advanced forward, and soon got upon firm

ground, where I sat down on a bank to rest myself, and consider what

I had best to do. When I was a little refreshed, I went up into the

country, resolving to deliver myself to the first savages I should

meet, and purchase my life from them by some bracelets, glass rings,

and other toys which sailors usually provide themselves with in those

voyages, and whereof I had some about me. The land was divided by

long rows of trees, not regularly planted, but naturally growing;

there was great plenty of grass, and several fields of oats. I walked

very circumspectly for fear of being surprised, or suddenly shot with

an arrow from behind or on either side. I fell into a beaten road,

where I saw many tracts of human feet, and some of cows, but most of

horses. At last I beheld several animals in a field, and one or two

of the same kind sitting in trees. Their shape was very singular, and

deformed, which a little discomposed me, so that I lay down behind a

thicket to observe them better. Some of them coming forward near the

place where I lay, gave me an opportunity of distinctly marking their

form. Their heads and breasts were covered with a thick hair, some

frizzled and others lank; they had beards like goats, and a long

ridge of hair down their backs and the fore parts of their legs and

feet, but the rest of their bodies were bare, so that I might see

their skins, which were of a brown buff colour. They climbed high

trees, as nimbly as a squirrel, for they had strong extended claws

before and behind, terminating in sharp points, and hooked. They

would often spring, and bound, and leap with prodigious agility. The

hair of both sexes was of several colours, brown, red, black, and

yellow. Upon the whole, I never beheld in all my travels so

disagreeable an animal, nor one against which I naturally conceived

so strong an antipathy. So that thinking I had seen enough, full of

contempt and aversion, I got up and pursued the beaten road, hoping

it might direct me to the cabin of some Indian. I had not got far

when I met one of these creatures full in my way, and coming up

directly to me. The ugly monster, when he saw me, distorted several

ways every feature of his visage, and stared as at an object he had

never seen before; then approaching nearer, lifted up his fore-paw,

whether out of curiosity or mischief, I could not tell. But I drew my

hanger, and gave him a good blow with the flat side of it, for I

durst not strike with the edge, fearing the inhabitants might be

provoked against me, if they should come to know, that I had killed

or maimed any of their cattle. When the beast felt the smart, he drew

back, and roared so loud, that a herd of at least forty came flocking

about me from the next field, howling and making odious faces; but I

ran to the body of a tree, and leaning my back against it, kept them

off by waving my hanger.  I ran to the body of a tree, and leaning my back against it, kept them off by waving my hanger

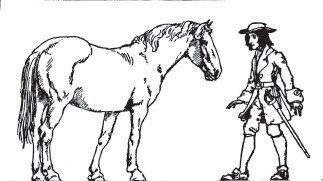

In the midst of this distress, I observed them all to run away on a sudden as fast as they could, at which I ventured to leave the tree, and pursue the road, wondering what it was that could put them into this fright. But looking on my left hand, I saw a horse walking softly in the field; which my persecutors having sooner discovered, was the cause of their flight. The horse started a little when he came near me, but soon recovering himself, looked full in my face with manifest tokens of wonder: he viewed- my hands and feet, walking round me several times. I would have pursued my journey, but he placed himself directly in the way, yet looking with a very mild aspect, never offering the least violence. We stood gazing at each other for some time; at last I took the boldness to reach my hand toward his neck, with a design to stroke it, using the common style and whistle of jockeys when they are going to handle a strange horse. But this animal seeming to receive my civilities with disdain, shook his head, and bent his brows, softly raising up his right fore-foot to remove my hand. Then he neighed three or four times, but in so different a cadence, that I almost began to think he was speaking to himself in some language of his own. While he and I were thus employed, another horse came up; who applying himself to the first in a very formal manner, they gently struck each other's right hoof before, neighing several times by turns, and varying the sound, which seemed to be almost articulate. They went some paces off, as if it were to confer together, walking side by side, backward and forward, like persons deliberating upon some affair of weight, but often turning their eyes towards me, as it were to watch that I might not escape. I was amazed to see such actions and behaviour in brute beasts, and concluded with myself, that if the inhabitants of this country were endued with a proportionable degree of reason, they must needs be the wisest people upon earth. This thought gave me so much comfort, that I resolved to go forward until I could discover some house or village, or meet with any of the natives, leaving the two horses to discourse together as they pleased. But the first, who was a dapple gray, observing me to steal off, neighed after me in so expressive a tone, that I fancied myself to understand what he meant; whereupon I turned back, and came near him, to expect his farther commands: but concealing my fear as much as I could, for I began to be in some pain, how this adventure might terminate; and the reader will easily believe I did not much like my present situation. The two horses came up close to me, looking with great earnestness upon my face and hands. The gray steed rubbed my hat all round with his right fore-hoof, and discomposed it so much that I was forced to adjust it better, by taking it off, and settling it again; whereat both he and his companion (who was a brown bay) appeared to be much surprised: the latter felt the lappet of my coat, and finding it to hang loose about me, they both looked with new signs of wonder. He stroked my right hand, seeming to admire the softness and colour; but he squeezed it so hard between his hoof and his pastern, that I was forced to roar; after which they both touched me with all possible tenderness. They were under great perplexity about my shoes and stockings, which they felt very often, neighing to each other, and using various gestures, not unlike those of a philosopher, when he would attempt to solve some new and difficult phenomenon. Upon

the whole, the behaviour of these animals was so orderly and

rational, so acute and judicious, that I at last concluded, they must

needs be magicians, who had thus metamorphosed themselves upon some

design, and seeing a stranger in the way, were resolved to divert

themselves with him; or perhaps were really amazed at the sight of a

man so very different in habit, feature, and complexion from those

who might probably live in so remote a climate. Upon the strength of

this reasoning, I ventured to address them in the following manner:

Gentlemen, if you be conjurers, as I have good cause to believe, you

can understand any language; therefore I make bold to let your

worships know, that I am a poor distressed English man, driven by his

misfortunes upon your coast, and I entreat one of you, to let me ride

upon his back, as if he were a real horse, to some house or village,

where I can be relieved. In return of which favour, I will make you a

present of this knife and bracelet, (taking them out of my pocket).

The two creatures stood silent while I spoke, seeming to listen with

great attention; and when I had ended, they neighed frequently

towards each other, as if they were engaged in serious conversation.

I plainly observed, that their language expressed the passions very

well, and the words might with little pains be resolved into an

alphabet more easily than the Chinese.

I could frequently distinguish the word Yahoo, which was repeated by each of them several times; and although it was impossible for me to conjecture what it meant, yet while the two horses were busy in conversation, I endeavoured to practise this word upon my tongue; and as soon as they were silent, I boldly pronounced Yahoo in a loud voice, imitating, at the same time, as near as I could, the neighing of a horse; at which they were both visibly surprised, and the gray repeated the same word twice, as if he meant to teach me the right accent, wherein I spoke after him as well as I could, and found myself perceivably to improve every time, though very far from any degree of perfection. Then the bay tried me with a second word, much harder to be pronounced; but reducing it to the English orthography may be spelt thus, Houyhnhnm.1 I did not succeed in this so well as the former, but after two or three farther trials, I had better fortune; and they both appeared amazed at my capacity. After

some further discourse, which I then conjectured might relate to me,

the two friends took their leaves, with the same compliment of

striking each other's hoof; and the gray made me signs that I should

walk before him, wherein I thought it prudent to comply, till I could

find a better director. When I offered to slacken my pace, he would

cry Hhuun, Hhuun; I guessed his meaning, and gave him

to understand, as well as I could, that I was weary, and not able to

walk faster; upon which, he would stand a while to let me rest.

_____________

1 The name is pronounced like "Whininim." |