| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER IX THE CONQUEST OF MOUNT EREBUS There was one

journey possible, a

somewhat difficult undertaking certainly, yet gaining an interest and,

excitement from that very reason, and this was an attempt to reach the

summit

of Mount Erebus. For many reasons the accomplishment of this work

seemed to be

desirable. In the first place the observations of temperature and wind

currents

at the summit of this great mountain would have an important bearing on

the

movements of the upper air, a meteorological problem as yet but

imperfectly

understood. From a geological point of view the mountain ought to

reveal some

interesting facts, and apart from scientific considerations, the ascent

of a

mountain over 13,000 ft. in height, situated so far south, would be a

matter of

pleasurable excitement both to those who were selected as climbers and

to the

rest of us who wished for our companions' success. After consideration

I

decided that Professor David, Mawson, and Mackay should constitute the

party

that was to try to reach the summit, and they were to be provisioned

for ten

days. A supporting-party, consisting of Adams, Marshall, and

Brocklehurst, was

to assist the main-party as far as feasible. The whole expedition was

to be

under Adams' charge until he decided that it was time for his party to

return,

and the Professor was then to be in charge of the advance party. In my

written

instructions to Adams, he was given the option of going on to the

summit if he

thought it feasible for his party to push on; and, he actually did so,

though

the supporting-party was not so well equipped for the mountain work as

the

advance-party, and was provisioned for six days only. Instructions were

given

that the supporting-party was not to hamper the main-party, especially

as

regarded the division of provisions, but, as a matter of fact, instead

of

hampering, the three men became of great assistance to the advance

division,

and lived entirely on their own stores and equipment during the whole

trip. No

sooner was it decided to make the ascent, which was arranged for,

finally, on

March 4, than the winter quarters became busy with the bustle of

preparation.

There were crampons to be made, food-bags to be prepared and filled,

sleeping-bags to be overhauled, ice-axes to be got out and a hundred

and one

things to be seen to; yet such was the energy thrown into this work

that the

men were ready for the road and made a start at 8.30 A.M. on the 5th. In a previous

chapter I have

described the nature and extent of equipment necessary for a sledging

trip, so

that it is not necessary now to go into details regarding the

preparations for

this particular journey, the only variation from the usual standard

arrangement

being in the matter of quantity of food. In the ascent of a mountain

such as

Erebus it was obvious that a limit would soon be reached beyond which

it would

be impossible to use a sledge. To meet these circumstances the

advance-party

had made an arrangement of straps by which their single sleeping-bags

could be

slung in the form of a knapsack upon their backs, and inside the bags

the

remainder of their equipment could be packed. The men of the

supporting-party,

in case they should journey beyond ice over which they could drag the

sledge,

had made the same preparations for transferring their load to their

shoulders.

When they started I must confess that I saw but little prospect of the

whole

party reaching the top, yet when, from the hut, on the third day out,

we saw

through Armytage's powerful telescope six tiny black spots slowly

crawling up

the immense deep snow-field to the base of the rugged rocky spurs that

descended to the edge of the field, and when I saw next day out on the

sky-line

the same small figures, I realised that the supporting-party were going

the

whole way. On the return of this expedition Adams and the Professor

made a full

report, with the help of which I will follow the progress of the party,

the

members of which were winning their spurs not only on their first

Antarctic

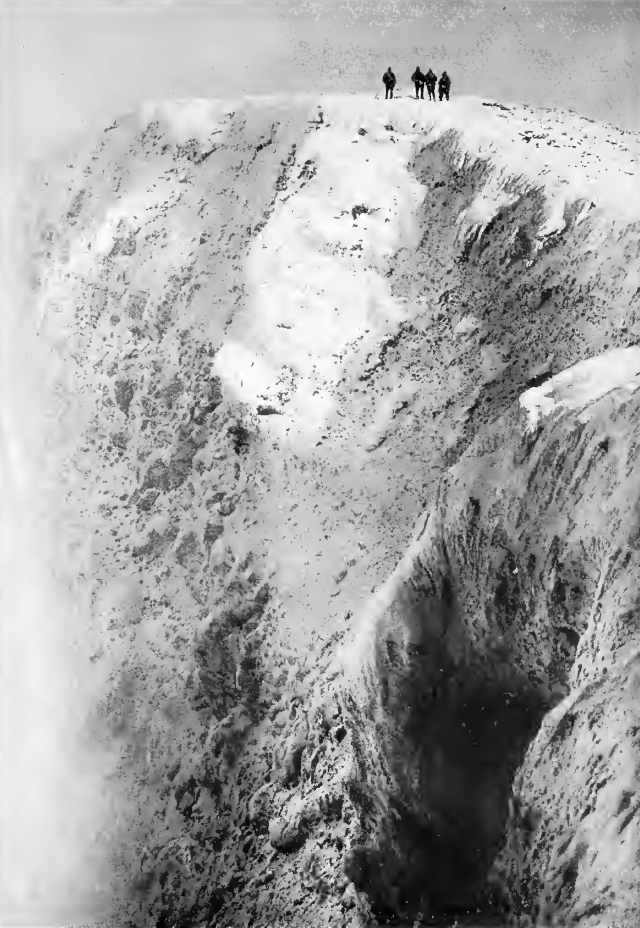

campaign, but in their first attempt at serious mountaineering. Mount Erebus bears a name that has loomed large in the history of polar exploration both north and south. Sir James Clark Ross, on January 28, 1841, named the great volcano at whose base our winter quarters were placed after the leading ship of his expedition. The final fate of that ship is linked with the fate of Sir John Franklin and one of the most tragic stories of Arctic exploration, but though both the Erebus and Terror have sunk far from the scenes of their first exploration, that brilliant period of Antarctic discovery will ever be remembered by the mountains which took their names from those stout ships. Standing as a sentinel at the gate of the Great Ice Barrier, Erebus forms a magnificent picture. The great mountain rises from sea-level to an altitude of over 13,000 ft., looking out across the Barrier, with its enormous snow-clad bulk towering above the white slopes that run up from the coast. At the top of the mountain an immense depression marks the site of the old crater, and from the side of this rises the active cone, generally marked by steam or smoke. The ascent of such a mountain would be a matter of difficulty in any part of the world, hardly to be attempted without experienced guides, but the difficulties were accentuated by the latitude of Erebus, and the party started off with the full expectation of encountering very low temperatures. The men all recognised, however, the scientific value of the achievement at which they were aiming, and they were determined to do their utmost to reach the crater itself. How they fared and what they found will be told best by extracts from the report which was made to me.  THE FIRST SLOPES OF EREBUS Pulling the

sledge proved fairly

heavy work in places; at one spot, on the steep slope of a small

glacier, the

party had a hard struggle, mostly on their hands and knees, in their

efforts to

drag the sledge up the surface of smooth blue ice thinly coated with

loose

snow. This difficulty surmounted, they encountered some sastrugi, which

impeded

their progress somewhat. " Sastrugi " means wind furrow, and is the

name given to those annoying obstacles to sledging, due to the action

of the

wind on the snow. A blizzard has the effect of scooping out hollows in

the

snow, and this is especially the case when local currents are set up

owing to

some rock or point of land intercepting the free run of the wind. These

sastrugi vary in depth from two or three inches to three or four feet,

according to the position of any rock masses that may be near and to

the force

of the wind forming them. The raised masses of snow between the hollows

are

difficult to negotiate with a sledge, especially when they run more or

less

parallel to the course of the traveller. Though they have many

disadvantages,

still there are times when their presence is welcome; especially is

this the

case when the sky is overcast and the low stratus cloud obliterates all

landmarks.

At these times a dull grey light is over everything, and it is

impossible to

see the way to steer unless one takes the line of sastrugi and notes

the angle

it makes with the compass course, the compass for the moment being

placed on

the snow to obtain the direction. In this way one can steer a fairly

accurate

course, occasionally verifying it by calling a halt and laying off the

course

again with the compass, a precaution that is very necessary, for at

times the

sastrugf alter in direction. The sledgers,

at this particular

juncture, had much trouble in keeping their feet, and the usual

equanimity of

some of the men was disturbed, their remarks upon the subject of

sastrugi being

audible above the soft pad of the finnesko, the scrunch of the

ski-boots, and

the gentle sawing sound of the sledge-runners on the soft snow. About 6

P.M.

the party camped at a small nunatak of black rock, about 2750 ft. above

sea-level and a distance of seven miles from winter quarters. After a

good hot

dinner they turned into their sleeping-bags in the tents and were soon

sound

asleep. The following morning, when the men got up for breakfast, the

temperature was 10° below zero Fahr., whilst at our winter quarters at

the same

time it was zero. They found, on starting, that the gradient was

becoming much

steeper, being 1 in 5, and sastrugi, running obliquely to their course,

caused

the sledge to capsize frequently. The temperature was 8° below zero

Fahr., but

the pulling was heavy work and kept the travellers warm. They camped

that

night, March 6, at an altitude of 5630 ft., having travelled only three

miles

during the whole day, but they had ascended over 2800 ft. above their

previous

camp. The temperature that night was 28° below zero Fahr. The second

camp was

in a line with the oldest crater of Erebus, and from the nature of the

volcanic

fragments lying around, the Professor was of the opinion that Erebus

had been

producing a little lava within its crater quite recently. On the

following morning Adams

decided that the supporting-party should make the attempt with the

forward-party to reach the summit. I had left the decision in this

matter to

his discretion, but I myself had not considered there would be much

shance of

the three men of the supporting-party gaining the summit, and had not

arranged

their equipment with that object in view. They were thus handicapped by

having

a three-man sleeping-bag, which bulky article one man had to carry;

they also

were not so well equipped for carrying packs, bits of rope having to

act as

substitutes for the broad straps provided for the original advance

party. The

supporting-party had no crampons, and so found it more difficult, in

places, to

get a grip with their feet on the slippery surface of the snow slopes.

However,

the Professor, who had put bars of leather on his ski-boots, found that

these

answered as well as crampons, and lent the latter to Marshall. Both

Adams and

the Professor wore ski-booth during the whole of the ascent. Ski could

not be

used for such rough climbing, and had not been taken. All the men were

equipped

with both finnesko and ski-boots and with the necessaries for camping,

and

individual tastes had been given some latitude in the matter of the

clothing

worn and carried. The six men

made a depot of the

sledge, some of the provisions and part of the cooking-utensils at the

second

camp, and then resumed the climb again. They started off with

tent-poles

amongst other equipment, but after going for half a mile they realised

it would

be impossible to climb the mountain with these articles, which were

taken back

to the depot. Each man carried a weight of about 40 lb., the party's

gear

consisting chiefly of sleeping-bags, two tents, cooking apparatus, and

provisions for three days. The snow slopes became steeper, and at one

time Mackay,

who was cutting steps on the hard snow with his ice-axe, slipped and

glissaded

with his load for about a hundred feet, but his further downward career

was

checked by a projecting ledge of snow, and he was soon up again. On the

third

evening, March 7, the party camped about 8750 ft. above sea-level, the

temperature at that time being 20* below zero Fahr. Between 9 and

10 P.M. that night a

strong wind sprang up, and when the men awoke the following morning

they found

a fierce blizzard blowing from the south-east. It increased in fury as

the day

wore on, and swept with terrific force down the rocky ravine where they

were

camped. The whirling snow was so dense and the roaring wind so loud

that,

although the two sections were only about ten yards apart, they could

neither

see nor hear each other. Being without tent-poles, the tents were just

doubled

over the top ends of the sleeping-bags so as to protect the openings

from the

drifting snow, but, in spite of this precaution, a great deal of snow

found its

way into the bags. In the afternoon Brocklehurst emerged from the

three-man

sleeping-bag, and instantly a fierce gust whirled away one of his

wolfskin mite;

he dashed after it, and the force of the wind swept him some way down

the

ravine. Adams, who had left the bag at the same time as Brocklehurst,

saw the

latter vanish suddenly, and in endeavouring to return to the bag to

fetch

Marshall to assist in finding Brocklehurst he also was blown down by

the wind.

Meanwhile, Marshall, the only remaining occupant of the bag, had much

ado to

keep himself from being blown, sleeping-bag and all, down the ravine.

Adams had

just succeeded in reaching the sleeping-bag on his hands and knees when

Brocklehurst appeared, also on his hands and knees, having, by

desperate efforts,

pulled himself back over the rocks. It was a close call, for he was all

but

completely gone, so biting was the cold, before he reached the haven of

the

sleeping-bag. He and Adams crawled in, and then, as the bag had been

much

twisted up and drifted with snow while Marshall had been holding it

down, Adams

and Marshall got out to try and straighten it out. The attempt was not

very

successful, as they were numb with cold and the bag, with only one

person

inside, blew about, so they got into it again. Shortly afterwards Adams

made

another attempt, and whilst he was working at it the wind got inside

the bag,

blowing it open right way up. Adams promptly got in again, and the

adventure

thus ended satisfactorily. The men could do nothing now but lie low

whilst the

blizzard lasted. At times they munched a plasmon biscuit or some

chocolate.

They had nothing to drink all that day, March 8, and during the

following

night, as it would have been impossible to have wept a lamp alight to

thaw out

the snow. They got some sleep during the night in spite of the storm.

On

awaking at 4 A.M. the following day, the travellers found that the

blizzard was

over, so, after breakfast, they started away again at about 5.30 A.M. The angle of

ascent was now

steeper.than ever, being thirty-four degrees, that is, a rise of 1 in

1i. As

the hard snow slopes were much too steep to climb without cutting steps

with an

ice-axe, they kept as much as possible to the bare rocks. Occasionally

the

artte would terminate upwards in a large snow slope, and when this was

the case

they cut steps across the slope to any other bare rocks which seemed to

persist

for some distance in an upward direction. Brocklehurst, who was wearing

ski-boots, began to feel the cold attacking his feet, but did not think

it was

serious enough to change into finnesko. At noon they found a fair

camping-ground, and made some tea. They were, at this time, some 800

ft. below

the rim of the old crater and were feeling the effects of the high

altitude and

the extreme cold. Below them was a magnificent panorama of clouds,

coast and

Barrier snow, but they could not afford to spend much time admiring it.

After a

hasty meal they tackled the ascent again. When they were a little

distance from

the top of the rim of the main crater, Mackay elected to work his way

alone

with his ice-axe up a long and very steep nova slope instead of

following the

less difficult and safer route by the rocks where the rest of the party

were

proceeding. He pasbed out of sight, and then the others heard him call

out that

he was getting weak and did not think he could carry oa much longer...

They

made haste to the top of the ridge, and Marshall and the Professor

dropped to

the point where he was likely to be found. Happily, they met him coming

towards

them, and Marshall took his load, for he looked much done up. It

appeared that

Mackay had found the work of cutting steps with his heavy load more

difficult

than he had anticipated, and he only just managed to reach safety when

he fell

and fainted. No doubt this was due, in part, to mountain sickness,

which, under

the severe conditions and at the high altitude the party had attained,

also

affected Brocklehurst. t Having found

a camping-place, they

dropped their loads, and the members of the party were at leisure to

observe

the nature of their surroundings. They had imagined an even plain of

neve or

glacier ice filling the extinct crater to the brim and sloping up

gradually to

the active cone at its southern end, but instead of this they found

themselves

on the very brink of a precipice of black rock, forming the inner edge

of the

old crater. This wall of dark lava was mostly vertical, while, in some

places,

it overhung, and was from eighty to a hundred feet in height. The base

of the

cliff was separated from the snow plain beyond by a deep ditch like a

huge dry

moat, which was evidently due to the action of blizzards. These winds,

striking

fiercely from the south-east against the great inner wall of the old

crater,

had given rise to a powerful back eddy at the edge of the cliff, and it

was

this eddy which had scooped out the deep trench in the hard snow. The

trench

was from thirty to forty feet deep, and was bounded by more or less

vertical

sides. Around our winter quarters any isolated rock or cliff face that

faced

the south-east blizzard-wind exhibited a similar phenomenon, though, of

course,

on a much smaller scale. Beyond the wall and trench was an extensive

snow-field

with the active cone and crater at its southern end, the latter

emitting great

volumes of steam, but what shrprised the travellers most were the

extraordinary

structures which rose here snd there above the surface of the

snow-field. They

were in the form of mounds and pinnacles of the most varied and

fantastic

appearance. Some resembled beehives, others were like huge ventilating

cowls,

others like isolated turrets, and others again resembled various

animals in

shape. The men were unable at first sight to understand the origin of

these

remarkable structures, and as it was time for food, they left the

closer investigation

for later in the day. As they walked

along the rampart of

the old crater.wall to find a camping-ground, their figures were thrown

up

against the sky-line, and down at our winter quarters they were seen by

us,

having been sighted by Armytage with his telescope. He had followed the

party

for the first two days with the glasses, but they were lost to view

when they

began to work through the rocky ground, and it was just on the crater

edge that

they were picked up again by the telescope.  ONE THOUSAND FEET BELOW THE ACTIVE CONE The camp chosen

for the meal was in

a little rocky gully on the north-west slope of the main cone, and

about fifty

feet below the rim of the old crater. Whilst some cooked the meal,

Marshall

examined Brocklehurst's feet, as the latter stated that for some time

past he

had lost all feeling in them. When his ski-boots and socks had been

taken off,

it was found that both his big toes were black, and that four more

toes, though

less severely affected were also frost-bitten. From their appearance it

was

evident that some hours must have elapsed since this had occurred.

Marshall and

Mackay set at work at once to restore circulation in the feet by

warming and

chafing them. Their efforts were, under the circumstances, fairly

successful,

but it was clear that ultimate recovery from so severe a frost-bite

would be

both slow and tedious. Brocklehurst's feet, having been thoroughly

warmed were

put into dry socks and finnesko stuffed with sennegrass, and then all

hands

went to lunch at 3.30 P.M. It must have required great pluck and

determination

on his part to have climbed almost continuously for nine hours up the

steep and

difficult track they had followed with his feet so badly frost-bitten.

After

lunch Brockiehurst was left safely tucked up in the three-man

sleeping-bag, and

the remaining five members of the party started off to explore the

floor of the

old crater. Ascending to the crater rim, they climbed along it until

they came

to a spot where there was a practicable breach in the crater wall and

where a

narrow tongue of snow bridged the neve trench at its base. They all roped

up directly they

arrived on the hard snow in the crater and advanced cautiously over the

snow-plain, keeping a sharp look-out for crevasses. They steered for

some of

the remarkable mounds already mentioned, and when the nearest was

reached and

examined, they noticed some curious hollows, like partly roofed-in

drains,

running towards the mound. Pushing on slowly, they reached eventually a

small

parasitic cone, about 1000 ft. above the level of their camp, and over

a mile

distant from it. Sticking out from under the snow were lumps of lava,

large

felspar crystals, from one to three inches in length, and fragments of

pumice; both

felspar and pumice were in many cases coated with sulphur. Having made

as

complete an examination as time permitted, they started to return to

camp, no

longer roped together, as they had not met any definite crevasses on

their way

Aut. They directed their steps towards one of the ice mounds, which

bore a

whimsical resemblance to a lion couch-ant, and from which smoke

appeared to be

issuing. To the Professor the origin of these peculiar structures was

now no

longer a mystery, for he recognised that they were the outward and

visible

signs of fumaroles. In ordinary climates, a fumarole, or volcanic

vapour-well,

may be detected by the thin cloud of steam above it, and usually one

can at

once feel the warmth by passing one's hand into the vapour column, but

in the

rigour of the Antarctic climate the fumaroles of Erebus have their

vapour

turned into ice as soon as it reaches the surface of the snow-plain.

Thus ice

mounds, somewhat similar in shape to the sinter mounds formed by the

geysers of

New Zealand, of Iceland and of Yellowstone Park, are built up round the

orifices of the fumaroles of Erebus. Whilst exploring one of these

fumaroles,

Mackay fell suddenly up to his thighs into one of its concealed

conduits, and

only saved himself from falling in deeper still by means of his

ice-axe.

Marshall had a similar experience at about the same time. The party

arrived at camp shortly

after 6 P.M., and found Brocklehurst progressing as well as could be

expected.

They sat on the rocks after tea admiring the glorious view to the west.

Below

them was a vast rolling sea of cumulus cloud, and far away the western

mountains glowed in the setting sun. Next morning, when they got up at

4 A.M.,

they had a splendid view of the shadow of Erebus projected on the field

of

cumulus cloud below them by the rising sun. Every detail of the profile

of the

mountain as outlined on the clouds could readily be recognised. After

breakfast, while Marshall was attending to Brocklehurst's feet, the

hypsometer,

which had become frozen on the way up, was thawed out and a

determination of

the boiling-point made. This, when reduced and combined with the mean

of the

aneroid levels, glade the altitude of the old crater rim, just above

the vamp,

11,400 ft. At 6 A.M. the party left the camp and made all speed to

reach the

summit of the present crater. On their way across the old crater,

Mawson

photographed the fumarole that resembled the lion and also took a view

of the

active crater about one and a half miles distant, though there was

considerable

difficulty in taking photographs owing to the focal plane shutter

having become

jammed by frost. Near the furthest point reached by the travellers on

the

preceding afternoon they observed several patches of yellow ice and

found on

examination that the colour was due to sulphur. They next ascended

several

rather steep slopes formed of alternating beds of hard snow and vast

quantities

of large and perfect felspar crystals, mixed with pumice. A little

farther on

they reached the base of the volcano's active cone. Their progress was

now

painfully slow, as the altitude and cold combined to make respiration

difficult. The cone of Erebus is built up chiefly of blocks of pumice,

from a

few inches to a few feet in diameter. Externally these were grey or

often

yellow owing to incrustations of sulphur, but when broken they were of

a

resinous brown colour. At last, a little after 10 A.M., on March 10,

the edge

of the active crater was reached, and the little party stood on the

summit of

Erebus, the first men to conquer perhaps the most remarkable summit in

the

world. They had travelled about two and a half miles from the last

camp, and

had ascended just 2000 ft., and this journey had taken them over four

hours.

The report describes most vividly the magnificent and awe-inspiring

scene

before them. "We stood on

the verge of a

vast abyss, and at first could see neither to the bottom nor across it

on

account of the huge mass of steam filling the crater and soaring aloft

in a

column 500 to 1000 ft. high. After a continuous loud hissing sound,

lasting for

some minutes, there would come from below a big dull boom, and

immediately

great globular masses of steam would rush upwards to swell the volume

of the

snow-white cloud which ever sways over the crater. This phenomenon

recurred at

intervals during the whole of our stay at the crater. Meanwhile, the

air around

us was extremely redolent of burning sulphur. Presently a pleasant

northerly

breeze fanned away the steam cloud, and ab once the whole crater stood

revealed

to us in all its vast extent and depth. Mawson's angular measurement

made the

depth 900 ft. and the greatest width about half a mile. There were ab

least

three well-defined openings at the bottom of the cauldron, and it was

from

these that the steam explosions proceeded. Near the south-west portion

of the

crater there was an immense rift in the rim, perhaps 300 to 400 ft.

deep. The

crater wall opposite the one at the top of which we were standing

presented

features of special interest. Beds of dark pumiceous lava or pumice

alternated

with white zones of snow. There was no direct evidence that the snow

was bedded

with the lava, though it was possible that such may have been the case.

From

the top of one of the thickest of the lava or pumice beds, just where

it

touched the belt of snow, there rose scores of small steam jets all in

a row.

They were too numerous and too close together to have been each an

independent

fumarole; the appearance was rather suggestive of the snow being

converted into

steam by the heat of the layer of rock immediately below it." While at the

crater's edge the party

made a boiling-point determination by the hypsometer, but the result

was not so

satisfactory as that made earlier in the morning at the camp. As the

result of

averaging aneroid levels, together with the hypsometer determination at

the top

of the old crater, Erebus may be calculated to rise to a height of

13,370 ft.

above sea-level. As soon as the measurements had been made and some

photographs

had been taken by Mawson, the party returned to the camp, as it had

been

decided to descend to the base of the main cone that day, a drop of

8000 ft. On the way back

a traverse was made

of the main crater and levels taken for constructing a geological

section.

Numerous specimens of the unique felspar crystals and of the pumice and

sulphur

were collected. On arriving in camp the travellers made a hasty meal,

packed

up, shouldered their burdens once more and started down the steep

mountain

slope. Brocklehursb insisted on carrying his own heavy load in spite of

his

frost-bitten feet. They followed a course a little to the west of the

one they

took when ascending. The rock was rubbly and kept slipping under their

feet, so

that falls were frequent. After descending a few hundred feet they

found that

the rubbly spur of rock down which they were floundering ended abruptly

in a

long and steep neve) slope. Three courses were now open to them: they

could

retrace their steps to the point above them where the rocky spur had

deviated

from the main arete; cut steps across the nevi) slope; or glissade down

some five

or six hundred feet to a rocky ledge below. In their tired state

preference was

given to the path of least resistance, which was offered by the

glissade, and

they therefore rearranged their loads so that they would roll down

easily. They

were now very thirsty, but they found that if they gathered a little

snow,

squeezed it into a ball and placed it on the surface of a piece of

rock, it

melted at once almost on account of the heat of the sun and thus they

obtained

a makeshift drink They

launched their loads

down the slope and

watched them as they bumped and bounded over the wavy ridges of neve.

Brocklehurst's load, which contained the cooking-utensils, made the

noisiest

descent, and the aluminium cookers were much battered when they finally

fetched

up against the rocks below. Then the members of the party, grasping

their

ice-axes firmly, followed their gear. As they gathered speed on the

downward

course and the chisel-edge of the ice-axe bit deeper into the hard

neve, their

necks and faces were sprayed with a shower of ice. All reached the

bottom of

the slope safely, and they repeated this glissade down each succeeding

snow

slope towards the foot of the main cone. Here and there they bumped

heavily on

hard sastrugi and both clothes and equipment suffered in the rapid

descent; unfortunately

also, one of the aneroids was lost and one of the hypsome ter

thermometers

broken. At last the slope flattened out to the gently inclined terrace

where

the depot lay, and they reached it by walking. Altogether they had

dropped down

5000 ft. between three in the afternoon and seven in the evening. Adams and

Marshall were the first to

reach the depot, the rest of the party, with the exception of

Brocklehurst,

having made a detour to the left in consequence of having to pursue

some lost

luggage in that direction. At the depot they found that the blizzard of

the 8th

had played havoc with their gear, for the sledge had been overturned

and some

of the load scattered to a distance and partly covered with drift-snow.

After

dumping their packs, Adams and Marshall went to meet Brocklehurst, for

they

noticed that a slight blizzard was springing up. Fortunately, the wind

soon

died down, the weather cleared, and the three were able to regain the

camp. Tea

was got ready, and the remainder of the party arrived about 10 P.M.

They camped

that night at the depot and at 3 A.M. next day got up to breakfast.

After

breakfast a hunt was made for some articles that were still missing,

and then

the sledge was packed and the march homewards commenced at 5.30 A.M.

They now

found that the sastrugi caused by the late blizzard were very

troublesome, as

the ridges were from four to five feet above the hollows and lay at an

oblique

angle to the course. Rope brakes were put on the sledge-runners, and

two men

went in front to pull when necessary, while two steadied the sledge,

and two

were stationed behind to pull back when required. It was more than

trying to

carry on at this juncture, for the sledge either refused to move or

suddenly it

took charge and overran those who were dragging it, and capsizes

occurred every

few minutes. Owing to the slippery nature of the ground some members of

the

party who had not crampons or barred ski-boots were badly shaken up,

for they

sustained numerous sudden falls. One has to experience a surface like

this to

realise how severe a jar a fall entails. The only civilised experience

that is

akin to it is when one steps unknowingly on a slide which some small

street boy

has made on the pavement. Marshall devised the best means of assisting

the

progress of the sledge. When it took charge he jumped on behind and

steered it

with his legs as it bumped and jolted over the sastrugi, but he found

sometimes

that his thirteen-stone weight did not prevent him from being bucked

right over

the sledge and flung on the nevi on the other side.  THE "LION" OF EREBUS Meanwhile, at

winter quarters, we

had been very busy opening cases and getting things ship-shape outside,

with

the result that the cubicles of the absentees were more or less filled

with a

general accumulation of stores. When Armytage reported that he saw the

party on

their way down the day before they arrived at the hut, we decided to

make the

cubicles tidy for the travellers. We had just begun on the Professor's

cubicle

when, about 11 A.M. I left the hut for a moment and was astonished to

see

within thirty yards of me, coming over the brow of the ridge by the

hut, six

slowly moving figures. I ran towards them shouting: "Did you get to the

top?" There was no answer, and I asked again. Adams pointed with his

hand

upwards, but this did not satisfy me, so I repeated my question. Then

Adams

said: "Yes," and I ran back to the hut and shouted to the others, who

all came streaming out to cheer the successful venturers. We shook

hands all

round and opened some champagne, which tasted like nectar to the

way-worn

people. Marshall prescribed a dose to us stay-at-home ones, so that we

might be

able to listen quietly to the tale the party had to tell. Except to

Joyce, Wild, and myself,

who had seen similar things on the former expedition, the eating and

drinking

capacity of the returned party was a matter of astonishment. In a few

minutes

Roberts had produced a great saucepan of Quaker oats and milk, the

contents of

which disappeared in a moment, to be fallowed by the greater part of a

fresh-cut ham and home-made bread, with New Zealand fresh butter. The

six had

evidently found on the slopes of Erebus six fully developed, polar

sledging

appetites. The meal at last ended, came more talk, smokes and then bed

for the

weary travellers. After some

days' delay on account of

unfavourable weather, a party consisting of Adams, the Professor,

Armytage,

Joyce, Wild and Marshall, equipped with a seven-foot sledge, tent, and

provisions, as a precaution against possible bad weather, started out

to fetch

in the eleven-foot sledge with the explorers' equipment. After a heavy

pull

over the soft, new-fallen snow, in cloudy weather, with the temperature

at

mid-day 20* below zero Fahr., and with a stiff wind blowing from the

south-east, they sighted the nunatak, recovered the abandoned sledge

and

placing the smaller one on top, pulled them both back as far as Blue

Lake. I

went out to meet the party, and we left the sledge at Blue Lake until

the

following day, when two of the Manchurian ponies were harnessed to the

sledges

and the gear was brought into winter quarters. Professor David

gave me a short

summary of the scientific results of the ascent, from which I have made

the

following extracts: "Among the

scientific results

may be mentioned the calculation of the height of the mountain. Sir

Jas. C.

Ross in 1841 estimated the height to be 12,367 ft. The National

Antarctic

Expedition, 1901, determined its height at first to be 13,120 ft., but

this was

subsequently altered to 12,922 ft., the height now given on the

Admiralty Chart

of this region. Our observations for altitude were made partly with

aneroids

and partly with a hypsometer. All the aneroid levels and hypsometer

observations have been calculated by means of simultaneous readings of

the

barometer taken at our winter quarters, Cape Royds. These observations

show that

the rim of the second or main crater of Erebus is about 11,350 ft.

above

sea-level and that the summit of the active crater is about 13,350 ft.

above

sea-level. The fact may be emphasised that in both the methods adopted

by us

for estimating the altitude of the mountain, atmospheric pressure was

the sole

factor on which we relied. The determination arrived at by the Discovery was based on measurements made

with a theodolite from sea-level. It is, of course, quite possible that

Ross'

original estimate may have been correct, as this native volcano may

have

increased in height by about a thousand feet during the sixty-seven

years which

have elapsed since his expedition." "As regards the

geological

structure of Erebus, there is evidence of the existence of four

superimposed

craters. The oldest and lowest and at the same time, the largest of

these

attained an altitude of between 6000 and 7000 ft. above sea-level, and

was

fully six miles in diameter: the second rises to 11,350 ft. and has a

diameter

of over two miles: the third crater rises to a height of fully 12,200

ft.; and

its former outline has now been almost obliterated by the material of

the

modern active cone and crater. The latter, which rises about 800 ft.

above the

former, is composed chiefly of fragments of pumice. These vary in size

from an

inch or so to a yard in diameter. Quantities of felspar crystals are

interspersed with them, and both are incrusted with sulphur. "The active

crater measures

about half a mile by one-third of a mile in diameter, and is about 900

ft. in

depth. The active crater of Erebus is about three times as deep as that

of

Vesuvius. The fresh volcanic bombs picked up by us at spots four miles

distant

from the crater and lying on the surface of comparatively new snow are

evidences

that Erebus has recently been projecting lava to great heights. "Two features

in the geology of

Erebus which are specially distinctive are: the vast quantities of

large and

perfect felspar crystals, and the ice fumaroles. The crystals are from

two to three

inches in length; many of them have had their angles and edges slightly

rounded

by attrition, but numbers of them are beautifully perfect. "Its remarkable

crystals, rare

lavas and unique fumaroles are some of its most interesting geological

features:

it served as a gigantic tide-gauge to record the flood level of the

greatest

recent glaciation of Antarctica, when the whole of Ross Island was but

a

nunatak in a gigantic field of ice. "Its situation

between the belt

of polar calms and the South Pole; its isolation from the disturbing

influence

of large land masses; its great height, which enables it to penetrate

the whole

system of atmospheric circulation, and the constant steam cloud at its

summit,

swinging to and fro like a huge wind vane, combine to make Erebus one

of the

most interesting places on earth to the meteorologist."  THE CRATER OF EREBUS, 900 FEET DEEP AND HALF A MILE WIDE. STEAM IS SEEN RISING ON THE LEFT. T HE PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN FROM THE LOWER PART OF THE CRATER EDGE |