| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2007 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER VI

SONGS WITHOUT WORDS ANATOMY shows us that the lower larynx, the syrinx or voice organ of singing birds, is the most marvelous musical instrument known, not excepting the prima donna's throat; that this organ, which is of the simplest form in birds of the lower orders, became more and more intricately complex the more highly birds developed, for song is of comparatively late achievement in their evolution; that the music which enchants us comes from where the bronchial tubes fork into the upper lungs; that a modulating apparatus, consisting of various kinds and numbers of bony half rings and muscles around the tubes and differing greatly with the different species, have much to do with a bird's scientific classification; that, by the automatic working of these muscles, musical messages of changeable tone and increased or diminished volume of sound may be sent at will through the tracheal sounding pipe all this and vastly more that is anatomical might be told; and yet a deaf person, who has never heard a bird sing, could form absolutely no idea of its music. "You cannot with a scalpel find the poet's soul,Nor yet the wild bird's song." Or, let

the

technical musician, whose trained ear catches the most delicate

gradations of

tone, attempt to write down, for example, the little house wren's

gushing

lyric. Again, impossible I Just as there are intervals in the African

negro's

melodies too subtle to be recorded on paper, although they are caught

by the

ear of each generation from its predecessor and passed on correctly to

posterity, so there is an elusive quality in bird music defying both

scientific

analysis and translation into set musical terms. As well try to convey

music

itself through a dictionary's definitions of it as to catch the

rollicking,

bubbling song of the bobolink on a printed page. Many

beginners in

bird study write to the ornithologist, asking him to name the songster

whose

music is laboriously described on an enclosed sheet. Staff, added

lines, clef,

time, bars, notes, sharps, flats, naturals, rests, accents all are as

carefully set down as if the inquirer were copying an intricate Bach

fugue; yet

not once out of ten times can the bird be named correctly by its

written song

alone, no matter how well up in field practice the ornithologist may

be: the

quality is lacking, and that is the very essence of the song. Lacking

that,

some description of size, plumage, or habit, must be mentioned to aid

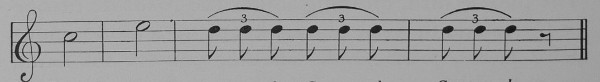

identification. CALL THE BIRDS TO YOU But catching bird music by ear is a different matter from writing it. Every farmer's boy knows that by crowing like his pet rooster he can make him reply, and that first one cock, then another, will echo the challenge, until every rooster in the neighborhood is set to flapping his wings and crowing with all his might. Certain wild birds have simple songs so pure of tone, or so slowly delivered, or so sharply accented, that the merest novice who can whistle has little difficulty in imitating them well enough to deceive even the feathered singer himself into thinking that one of his kind is replying from the wood. One can "whistle up" silent birds, too, trying first one call, then another, to learn what bird is within hail; then, hearing a reply in the far distance, bring the minstrel nearer and nearer to investigate the freaky song so like his own and yet so different! that curiosity must be satisfied by closer inspection, until he frequently gets near enough to photograph, if not to touch. No birds are more readily attracted than the friendly little chickadees, whose three very more high, clear call-notes, once heard, are easily imitated. A gorgeous minstrel - the Baltimore oriole The quail on the outskirts of the farm calls back a cheerful "bob-white" to your sharp staccato whistle, and quite as promptly as if you were a sentry demanding "Who goes there?" Timid plover hiding in the grain fields utter a plaintive, almost petulant kill-dee, kill-dee to one who can call them by name. The phoebe bird, building under the roadside bridge or the rafters of your piazza, keeps up a monotonous pewit phoebe, pewit phoebe whether you ask his name or not, although even he likes to hear it called. His relative, the wood pewee, whose song in B-flat minor suggests a rather melancholy religieux living apart from this wicked world, is quite ready to repeat his "one sweetly solemn thought," which "comes to him o'er and o'er" at your suggestion. Indeed, nothing seems to daunt this pensive minstrel. When midsummer silences nearly every other voice he still sings on, with the indigo bunting and the red-eyed vireo. How refreshing is the song sparrow's cheerful, merry, but alas! inimitable, outburst after the solemn pewee! But one soon learns that the bird music which really enchants us the bobolink's, cardinal's, thrush's or mocking-bird's, for example, can never be imitated by human lips, albeit birds and humans are the only creatures that can sing. Andrew Carnegie said he would as lief shoot an angel as a song-bird, for both must he akin because they sing and fly.  While a good whistler obtains satisfactory results by repeating after the birds certain of the simplet songs until they are learned perfectly, it is quite a different matter to so record them on paper that one who had never heard them before could whistle them off, like ordinary tunes from a book, well enough to deceive the feathered songsters themselves. I doubt if it could be done. Take, for instance, the white-throated sparrow's familiar, well-defined strain. When this comes to be set down in cold type, no two books in the library record it alike. New Englanders think the bird devotes his vocal energies to glorifying "Old Sam Peabody," while our British cousins, over the border, are so certain that he sings the praises of their land they actually call him the Canada sparrow. "What's in a name?" All sorts of phrases, in words of three syllables, have been fitted to this strain in various sections, yet however differently people record the song, it is perhaps the only one written the one out of every ten submitted by which the persecuted ornithologist could correctly name the bird without further description. The sets of triplicate notes identify it, not the words which imagination supplies. But print can convey no idea of the exquisite quality of that high-pitched, piercing, sweet, tenderly plaintive strain. Whistle it from memory, in the cool of a spring day, in some deep northern forest perhaps not one, but a half a dozen white-throats will pierce the evening stillness, complimenting your poor performances as no opera singer yet was encored.

Swee . . .

eet

Can-a-da,

Can-a-da,

Can-a-da, HOW BIRDS LEARN TO SING It is

nature's only

way to teach sound by ear and still the most exact. As a child is

born a

certain racial type of linguist and learns to speak by imitating the

words in

daily use about him, so a bird enters life the kind of singer that he

is and learns

his notes by imitating those of his closest associates. Only, the more

clever

young child, given an equal opportunity to hear two languages, acquires

one as

readily as the other; while the bird, in a state of nature, usually

confines

its notes to the traditional ones of its clan, although it may hear the

notes

of scores of other species every day of its youth. Certain very young

European

goldfinches, isolated from others of their kind, showed a decided

tendency to

repeat only the notes of the caged songsters about them; still, they

used some

inherited notes, too, and these, with the inherited quality of voice,

made

their song sufficiently characteristic of the species to be

recognizable. Many

more experiments are necessary, however, to prove with scientific

accuracy

that a bird even partially inherits his song. We know that expert

trainers have

taught the bullfinch to whistle "Yankee Doodle." The mocking-bird is

by no means the only mimic. A certain pet canary could so perfectly

imitate the

English sparrows that came about his cage on the porch to pick up the

waste

seed, that it was only by watching the movements of the feathers on his

throat

that one could believe it was he who was amusing himself by imitating

the

chirpings and twitterings of an entire sparrow flock. Probably a

bird

both inherits and acquires his notes; otherwise, how could we account

for the

many variations of the same song rendered by different birds of the

same

species? No two canaries in any shop sing precisely alike, although all

may

have been hatched in the same peasant's house in the Hartz Mountains.

In every

case individuality reveals itself in shrillness or mellowness of tone,

in the

low, sweet, tender warble, or the sharp, almost vindictive roundelay

incessantly repeated with the evident desire to overpower all rivals;

yet we

recognize the canary in each song. To the general characteristics of

the

species we must add individuality of temperament and the training

received from

the individual's associates before we can understand any bird's music. Travelers in the Canary Islands say that the wild canaries there are by no means so skilled musicians as the caged singers. Doubtless the bird's voice has been improved by cultivation as much as his feathers, which, originally, were greenish gray and brown, when canaries were first imported into Europe in the sixteenth century. Nevertheless, our own wild songsters show almost, if not quite, as much diversity as the caged canaries when we concentrate our study on the music of a single species. The chief American songster - a young Mocking-bird How many people who have spent their lives in the country recognize all the songs and calls even of the robin? Probably he is the first bird we learned to know by name. Among the first arrivals and the latest stayers, he lives on terms of neighborly intimacy with us at least two-thirds of every year; yet the fact that twenty-five distinct songs and calls have been recorded of a single individual by one who took no pains to study robin music in different sections of the country where bird voices differ as greatly as human dialects causes many people to lift their eyebrows with an incredulous "Is it possible?"  First call for breakfast How his

first

salute to spring electrifies us with good cheer! The hair-sparrow's

wiry little

trill has scarcely roused the sleeping choir at dawn when he begins a

subdued

warble, which gradually increases with the morning light until, his

throat

attuned and all his powers fully alert, he bursts at last into the

splendid

exuberant performances which so delight us. Everybody knows it. Heard

at its

best, none is more exhilarating and few are more beautiful, but even

his own

meditative, tender, warbled even-song excels the matins. Then there are

two

less familiar strains given before and after rain, the exquisite love

song

without words yet perfectly understood, a call of caution to his mate,

a clear,

vigorous, ringing, military alarm, a signal to take wing, a summons to

his

comrades when they have gathered in an autumn flock, a self-conscious

brag, an

outburst of temper, endearing, coaxing notes for the young, scoldings

for the

cat, and so on through the gamut of his experiences. There appears to

be a

different vocal expression for each. And he has an old trick of humming

to

himself with his mouth closed, as if practicing for public recitals,

the most

humorous performance of all, if you have the good fortune to surprise

him at

it. WHY BIRDS SING

A study of

farmyard

poultry reveals a surprising number of call-notes in common use among

chicks,

hens and roosters, not to mention the ejaculations reserved for such

unusual

occurrences as the sudden swoop of a hawk or the headsman's axe. Forty

distinct

utterances do not exhaust their vocabulary. Here, better than

elsewhere, we may

observe the necessity for every call-note and its fitness, and apply

some of

our knowledge to the less accessible songbirds. But a call

is quite

different from a song, and was doubtless evolved ages before it. One is

a first

necessity, the other a highly desirable but secondary acquisition

generally

attained only by the male. For the same reason that a rooster crows

to

challenge his rivals or to make a favorable impression on the hens of

his

acquaintance does a bird sing, and the more refined and beautiful his

voice

the higher does he rank in the books. Bird music means vastly more than

a crow,

gobble, boom, or drumming. It indicates the triumph of the higher

nature over

the lower; it may become the expression of those qualities which we

usually

associate with soul. "No original water-haunter or ground-builder ever

sang," says James Newton Baskett. "Every melody is a march a

command to move onward to the ear that can truly comprehend it." INSTRUMENTAL

PERFORMERS

For the sake of advertising their location as well as to please, some birds that can't sing resort to curious expedients. The prairie-cock inflates two loose yellow sacs on the sides of his head that stand out like small oranges. From these he lets out air to produce a booming sound, powerful, penetrating like the deep tones of an organ, which he repeats again and again until the whole neighborhood reλchoes and all rival cocks have been challenged to boom more loudly than he. Then all assemble, to fight with beak and claws, on their favorite "scratching ground," in the presence of an admiring circle of hens. The prize-fight among birds indicates no higher plane of development than among humans. We don't expect much of gallinaceous fowls. A favorite booming log and trysting place (Canada grouse) Another of

these,

the ruffed grouse, usually mounts a fallen log, preferably one that has

served

many seasons as a drumming and trysting place. At first slowly beating

his

wings, he moves faster and faster, until there is only a blur where the

wings

vibrate too rapidly for human sight to follow. Without touching the log

with

his wings, striking only the air, he beats a rolling tattoo, a deep,

muffled,

sonorous, crepitating whir-r-r-r that

serves as advertisement, challenge, love

song, and an outlet to his inordinate vanity and vigorous animal

spirits. Every

sportsman knows that sound of

the drummer without a drum. When the nighthawk drops downward from a great height, his outstretched wings and tail create an ζolian instrument which gives forth the jarring, booming, whirring noise that is more weird than musical. The flicker - our only woodpecker vocalist With the

exception

of the flicker a law unto himself among his clan our native

woodpeckers are

instrumental performers only. The rap-tap-tapping of their bills

against the

tree trunks is as cheerful music as any in the spring woods. The

sapsucker

hammers his vigorous, impetuous, staccato proposal with more sense of

musical

values, perhaps, than the others; but all are musicians, though they

can't sing

a note. Songless birds have found various ways of expressing their

sentiments.

Some dance, some ogle, and none is more ridiculous in his antics to woo

the

well-beloved than the flicker, whose vocal accomplishments are by no

means to

be despised. All the woodpeckers delight in sound, however produced.

Hairy and

Downy frequently tap on the tin roofs and gutters of our houses simply

because

they like the noise. A pair of red-headed woodpeckers reared their

family in a

hollow tree next the railroad track in the station-yard at Atlanta,

where the

smoke of every passing locomotive enveloped their house; but engineers

let off

steam and do much bell-ringing when about the yards, and these

woodpeckers

evidently enjoyed the din enough to compensate them for the smoke and

publicity. To hear

the

kingfisher flying up stream advising his mate that he is coming home,

one might

suspect that he, too, is an instrumentalist, his instrument being a

policeman's

rattle. The cuckoo also has a peculiar rattle, kr-r-r-r-r-uck-uck-uck,

suggesting a great tree-toad; but neither of these birds may be used to

swell

the short list of instrumental performances. Both are vocalists. PEERLESS MUSICIANS

But when

we speak

of vocalists no one has in mind either kingfisher or cuckoo, or the

screaming

blue jay that goes roving about through the autumn woods with a troop

of noisy

fellows, or his cousin the crow, or the wheezy grackles whose notes

suggest

wagon-wheels in need of axle-grease, or the uncanny owls whose hoots

make night

hideous, or strident hawks, or wild geese honking as they speed high

above us

in a wedge-shaped flock. To him that hath ears to hear even these are

musical.

No; the real star performers of the world are such as buy no castles in

Wales

with the proceeds of a single concert tour, but shy, often persecuted

creatures, which, like the hermit thrush, lift up their heavenly voices

in

woodland solitudes with only a devoted little mate for an audience.

Love alone

inspires these highest attainments. Neither for applause nor hope of

gain does

the mocking-bird fill the southern groves with its enchanting melody,

or

thrushes peal their silvery bell-like notes through northern woods. For

beggar

or king the humble little field-sparrow makes no variations of its

exquisite

song. The gorgeous cardinal's rich whistle, the bobolink's hurried,

tripping

cadenzas, the wren's tuneful frolic, the vesper-sparrow's hymn-like

benediction

at close of day all are free as salvation! It is the unearthly,

soulful

quality in a bird's voice that thrills one with shivery creeps of

sympathetic

vibration. An instramentalist with a call like a policeman's rattle - Kingfisher The blue jay - mimic, ventriloquist, tease and rascal The wood-thrush WHEN BIRDS SING

In

February, before

we have begun to look for pussy-willows or skunk-cabbages, the

song-sparrow's

sweet, sprightly bluebirds, blackbirds, and other "merry cheer" opens

the concert of bird music. Presently robins, bluebirds, blackbirds, and

other

migrants returning from the south in advance of the females, burst into

joyous

songs of expectancy, e very day adding some new minstrel to the choir,

until

toward the end of spring the birds are holding such a May festival as

Theodore

Thomas never conducted. Late in the merry month nearly every throat

that can

make music is rippling, whistling and warbling its utmost best; for a

bird's

season of song usually corresponds with its nesting season. Some

musicians, it

is true, attune their voices long before the courting days, yet in

anticipation

of them; and they still have enough vitality left after they have

helped raise

two broods and have molted their feathers, to express enjoyment of life

in

song. Either or both of these physical strains is enough to stop some

birds'

melody altogether. One rarely hears a bobolink after the fourth of

July. Few

birds, indeed, attempt to sing after family cares and midsummer heat

and the

growing of new feathers deject their spirits. Such as continue through

these

ordeals usually drop so many notes that one can scarcely recognize the

broken

fragments of their real song. But after the new suit of clothes is well

on,

whether it is joy in the possession of them or a returned sense of

physical

well-being, in early autumn a second singing usually begins not so

long, nor

so exuberant, nor so pleasing, but still a welcome reminder of spring

joys. The song-sparrow chooses a conspicuous perch for his performance THE DEVELOPMENT OF

BIRD AND HUMAN MUSIC

Whether the evolution of bird music has paralleled that of our own is not yet a settled question among scientists, but a great mass of evidence seems to prove that it has followed similar lines, and that its tendency is still toward the same ideal. We have already noted that it is the quality of voice, not so much the intervals of the melodic scale, that differentiates avian from human music. That sense of rhythm is variously developed among birds we realize on comparing the Carolina wren's precisely emphasized beats with the jumbled jargon of that rollicking polyglot, the Maryland yellow-throat. All the intervals of the major and minor scales that we can write, as well as some too elusive to record, are used by birds in perfection of tone. They employ very effectively repetitions of notes and phrases, sometimes so combined as to produce a formal theme, some birds of quite limited powers thus producing the most pleasing results. They trill on two notes or more, introducing a finer tremolo than a pipe-organ's. Antiphonals are indulged in by several of the tuneful sparrows, chewinks and meadowlarks; in short, they make unconscious use of musical intervals and methods that men have formulated into laws. Because they are laws, we are just beginning to realize that they may be of wide enough application to include the birds' music. Above all, there is a purity, an exquisite quality of a bird's song, with which no other on earth is to be compared. That music such as theirs can be written at all in the set forms that we use for ours would seem to indicate that the lines of development of both are not so divergent as one at first might suppose. Foremost critics declare that the opera and oratorio of the future will be sung, like bird music, without words. One of our sweetest though unappreciated songsters - the rose-breasted grosbeak |