|

CHAPTER

XV

WHAT THE BASKET MEANS TO THE INDIAN BY NELTJE BLANCHAN NOT through a written literature, not through music, architecture, sculpture or painting, as we understand the fine arts, has the North American Indian yet expressed the intellectual and spiritual aspirations of the race; but chiefly through the artistic handicrafts of the women. While primitive man, of all races, waged war and hunted, of necessity, primitive woman was ever the constructive element in society, the homemaker, the conserver of industry and thrift, the manufacturer, through simple, homely processes, of the raw products of nature into useful and sometimes beautiful forms, the inventor of many crafts, the mother of the arts, the nurse of religion. To mention only one of her contributions to civilization, there is the textile handicraft, invented by aboriginal women the world around to meet the need for shelter, clothing, hats, cradles, fish and snaring nets, mats and baskets; and so thoroughly did they master the intricacies of weaving, that not a single new stitch has been added to the sum of primitive knowledge by the most skilled modern craftsmen. At the point where primitive women left off, civilized men, at a comparatively recent date, were able to take the work from their hands, apply machinery to it and convert the manufacture of textiles into one of the great staples of commerce for the world. Through the same phases of development all races of mankind must pass, ethnology teaches us, and today our Indian woman is where Egyptian, Roman, Teuton, Frank and Briton women once were before their respective races attained civilization and culture. Like the Indian weaver in the West today, where civilization has not yet effaced her, these women of the ancient world were once the weavers for their people; references to their spinning, weaving, and basketry abound in early literatures, and examples of their similar work, still extant in museums, testify to the sisterhood of the human race. Into all these primitive home-made articles, beauty slowly found greater and greater expression in form, color and design; and it was often wrought out through materials so crude and difficult to manipulate as to make one wonder that effort to transform them was even attempted.

WICKER SCOOP—For gathering acorns and piñon nuts. BASKET BOWLS—In which acorns are boiled by the use of hot stones. A BOTTOMLESS BOWL—Plated over a hollow stone in which dried acorns are ground into meal. DINNER PLATES—Used by the Hupa Indians, California (Courtesy of The American Museum of Natural History, New York) Civilized man has yet to discover a use for the fretful porcupine, but Indian women have used its quills for centuries to embroider designs on household articles made of skin and bark. The Pimas and Apaches, living in the alkali desert of Arizona, utilize the "cat claws," the hard, stiff, black seed vessels of one of the few plants that can grow on their arid reservations, to weave the Greek key pattern, the mystical Swastika of India and Egyptian-like geometric, symbolic designs into their wonderful willow baskets. How much beauty would you and I attempt to put into our cooking utensils and articles of. commonest household use with such a pitiful poverty of material? With a more scientific appreciation of primitive woman's contribution to modern civilization must come a sympathetic interest in the handicrafts of our Indian woman, whose slow steps in upward progress we may even now behold her taking for her people. We may see the early industrial history of our own race repeating itself in the Western world. Chief among the Indian's handicrafts is basketry: the most expressive vehicle of the tribe's individuality, the embodiment of its mythology and folk-lore, tradition, history, poetry, art and spiritual aspiration — in short, it is, to the Indian mind, all the arts in one. Moreover, it is his most useful handicraft, serving him from the cradle to the grave. In a deftly woven bassinet, ornamented with shells, gay feathers or bits of bright cloth, such as any baby would enjoy, the Indian mother ties her papoose. Hanging the cradle from a sheltering tree while at work about the camp, or suspending it from her strong shoulders when she must wander afield, she allows the precious contents to interrupt her regular labors but little. Here, as in everything she makes, is the simple, perfect adaptation of the article to its uses which gives primitive handiwork everywhere so great an interest. It is only after we attain civilization that the meaningless multiplication of the unnecessaries begins. When there is not a baby on her back the squaw has other burdens to carry — wood for the camp-fire, meat from the hunt, fish, grain, nuts, fruit and water; and, again, netted twine or woven basket serves every purpose. One of the most beautiful and expressive designs ever made by an untutored hand was wrought out in a large bag of netted yucca fibre deliberately manufactured as a wood carrier by a bronze savage girl in one of the out-of-the-way corners of the Southwest.

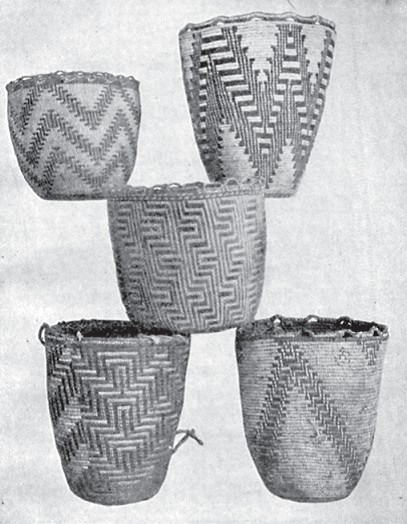

KLIKITAT AND QUINAIELT CARRYING BASKETS (Oregon and Washington) Designs represent mountains, streams, rippling waves and fertile valleys, where the plumed quail abounds (Courtesy of The American Museum of Natural History, New York) The shapes of carrying baskets differ widely. Originally both food and water were doubtless carried in hollow gourds enclosed in netted twine to give additional strength, and a stick slipped through the meshes made their transportation easy. But in due time the basket evolved from netting, and the cone-shaped carrying-baskets made by certain Western tribes today are of exceedingly beautiful workmanship. The finely woven decorations represent in symbolic, conventionalized form those familiar natural objects so dear to the Indian heart — mountains, lakes, streams, trees, sea waves or water fowl, for example — objects with which the particular tribe has closest association. These are the subjects such as ever stir the Indian artist's imagination. How can water be carried in a basket? one may well ask. Strangely enough, the tribes living in the arid Southwest, where every drop of water is exceedingly precious, are the very ones which chiefly trust to basket water-carriers. No danger of the pitcher breaking at an Indian well. The Paiutes, who make water-jars for their own use, and to barter for blankets with the Navajo, weave them of willow strippings and coat them with gum from the piñon pine. Many baskets made by various tribes are tightly enough woven, however, to hold water even without a gum coat. The bottom of the wicker water-bottle, made by the Havasupais in Cataract Cañon, Arizona, tapers to a point, which the Indian sticks into the ground to prevent the bottle from overturning. Handles of braided horsehair, which never break, confine the leather strap by which the squaw suspends the bottle from her head or her pony's saddle. Such bottles may be made to contain a pint or several gallons of water. In the division of labor among primitive people, at least, women have always taken charge of the family larder. For collecting, preparing, cooking and serving food, basketry is still most important to the Indian. To gather the nuts under the piñon trees in the Rocky Mountain region, she fashions a spoon-shaped wicker scoop, whose bowl is also a coarse sieve through which the dirt is shaken. Huge storage baskets, representing tens of thousands of stitches, are often as tall as a man, as symmetrical as a Greek vase, and they are laboriously ornamented with symbolic designs which convey whole volumes of meaning to members of the tribe. The White Mountain Apaches, among others, make some wonderful household granaries. Into these great baskets the Indian housekeeper pours the nuts, acorns, fruit, maize, and other grains on her return from nature's market in the woods and fields.

ALASKAN WALLETS, CARRYING BASKETS, TREASURE BASKETS, PLATES AND ALEUTIAN EMBROIDERED WALLET (Courtesy of The American Museum of Natural History, New York)

Every Indian woman is her own miller. Going to a favorite rock, hollowed on its upper surface by much grinding, she places upon it a bowl-shaped but bottomless basket to confine the portion of grain being ground, as well as to prevent the wind from blowing away her meal. Through the hole in the bottom of the basket she works her stone pestle diligently until all the grain is ground fine. Even a prosaic basket like this one does not lack its appropriate, poetic symbols. A wicker winnower, to separate the grain from the chaff, is usually shaped like a large scallop shell, suggesting its probable derivation before the Indians were driven backward from the coast into the interior. A basket through which to sift the finer flour is a necessary utensil in every well-regulated Indian household. Today Chinese merchants still sift tea through basket trays. The slightly hollowed basket plaque, which is one of the commonest and most widely distributed shapes, may be used as a meal tray in the pueblo home, or, heaped with propitiatory gifts to appease the wrath of an angry god, may adorn the village altar; again it is seen in use among the gamblers, who toss their dice upon it; at ceremonial dances of several tribes it is most important; the Navajo wedding feast cannot be eaten from any other dish; and when an Indian dies, members of the family reverently place food in basket plaques on the ground around his grave, that his spirit may refresh itself on its visits to earth. Because of the number of tribes using the plaque, and the great variety of uses to which it is put, no form of Indian basket shows more varied weaves and wider range of decorative design. To interpret Indian symbols without the help of the squaw who worked them out of her own inner consciousness, to get at the thought of the individual weaver, taking into due consideration the mental idiosyncrasies of her tribe, as one must do before the decoration can be rightly understood, is an exceedingly difficult task which the enthusiast with a lively imagination would better leave to the scientific investigator. But no student of races, of the evolution of art, of folk-lore or of comparative religions, can afford to neglect the Indian basket. And the study cannot begin too soon, for basketry has either deteriorated sadly wherever the white people's civilization has penetrated, or it has totally disappeared. In one small collection of meal plaques alone are found three whose decorations tell of the creation of the world according to the legends of as many tribes; another plaque shows four streams flowing in regular, beautiful lines from a lake in the centre to the edge; a Hopi, yucca plaque, with unfinished end, reveals the age of the girl who wove it; a spider-web design wrought into another, is a prayer for rain to the spirit which presides over the gossamer clouds that bring it to the suffering people in the desert; a circle set with small stars represents the constellation Corona; a star which radiates toward every point of the compass may be read as a petition for favorable winds while the crops are growing, and yet, to another tribe, the same design may have a totally different significance. But every line on an Indian basket is eloquent with meaning if we could but interpret it — that is what makes the study of basketry so interesting to the collector and so important to the scientist. A pattern which looks like a flash of lightning to desert Indians, whose every thought is directed toward signs of rain, may mean a mountain stream to a tribe living among the Sierras, or, again, it may be intended to represent the incoming tide to Indians with homes near the sea. Still another grain plaque in this small collection, has for its border the rattlesnake's markings conventionalized, and it is a prayer laboriously and fervently expressed, asking for protection of the weaver's loved ones from the deadly rattler. This design, with various modifications which include the St. Andrew's cross, is especially common among the Indians in Northern California and Alaska, whose exquisite basketry, rich in symbolism, is not surpassed by any people in the world. The acorn is a staple article of food among several tribes, but before it is fit for the human stomach it must first be boiled. How is the Indian, who has no pottery and who never saw an iron kettle, to boil her food? In California there are still to be seen a few squaws cooking in watertight baskets after the primitive method of their ancestors. Stones heated at a neighboring fire are tossed into the water until it is brought to the boiling point, and there it is kept by the addition of more hot stones until the acorns are cooked. Now all the bitterness is gone, and when dry again they are ready to be pounded into meal. The cooking basket of the Hoopa Valley Indians, for example, is a thing of beauty, with mountain peaks and flowing streams on its shapely sides. How repulsively ugly are the civilized cook's machine-made kitchen utensils compared with these hand-wrought vessels in which the Indian woman delights! With genuine artistic feeling she fashions her kettle from shreds of the red bud, mountain grasses, colored with natural dyes, and stems of the maiden hair fern, the whole often representing weeks of work.

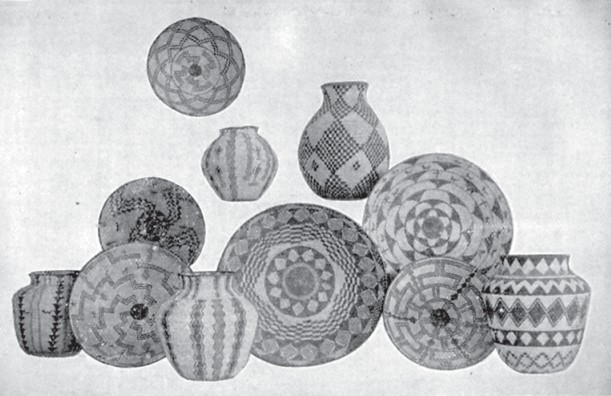

APACHE GRAIN PLAQUES AND JARS (Arizona) All made from the sisal willow strippings and the blank reed vessels of a desert plant (Martynia) popularly known the "Cat Claws" (Courtesy of The American Museum of Natural History, New York) Ages before people had pottery to cook in they had basketry, which is, indeed, the oldest and the most universally practised handicraft known. Perhaps a hunter returned home hungry one day in the far away past, and his wife, anxious to hasten dinner for her impatient lord, coated her cooking basket with clay that she might set it directly over the fire without danger of burning. Imagine the woman's surprise and joy to find on removing it from the embers after dinner that she had a basket plus an earthenware pot! Thus directly from basketry was pottery evolved. One finds the same shaped vessels of clay as of wicker work among the Zuñi and other potters, and the same decorations in many instances on both. Moreover the Havasupai still use clay-lined basket-plaques to hold glowing wood embers and kernels of corn, which are kept dancing together by the dexterous cook until the corn is parched; meanwhile the clay hardens. Numbers of good cooking utensils are thus produced Far to the North, where the cedar tree furnishes the wretched natives with practically every comfort they have, wooden cooking boxes, fashioned from its trunk, hold the water into which hot stones are tossed when fish or blubber is to be boiled. Clothing is woven from shredded cedar bark and mats for the weaver to sit upon. But even in this desolate, poor land, an earnest striving after some expression of beauty is seen. In the most remote islands in the Aleutian chain, the Indian woman, unrewarded by applause or hope of gain, weaves exquisitely fine, dainty treasure baskets, being impelled by impulses as natural as those of a bird whose weaving is scarcely less amazing. The longest, hardest journey is not too wearisome to deter a squaw from going to collect rare roots and grasses or dyeing material; a lifetime is not too long to perfect herself in the handicraft bequeathed to her as a tribal trust from former generations. When vegetable fibres seem inadequate for all the beauty she fain would express, the Poma weaver in California, adds rare feathers, wampum, abalone, and sometimes bits of silver, although the finished marvel is destined for the bonfire in the death dance ceremonial. One of these exceedingly fine Poma feather baskets, which is always as valuable as a pony, was recently sold to a museum for eight hundred dollars. "Datso-la-lee," a Washoe weaver whose skill is probably unrivaled in any land, has recently made an intricate basket that was sold for eighteen hundred dollars to a private collector, and he possesses a masterpiece of art as truly as the connoisseur who invests thrice that sum in a piece of bronze or a painting. If the Indian woman reaped the profit of her toil, and not the frontier trader (who is a shark in far too many instances), there might be greater hope of preserving the native industries. As it is, they are perilously near becoming among the lost arts.

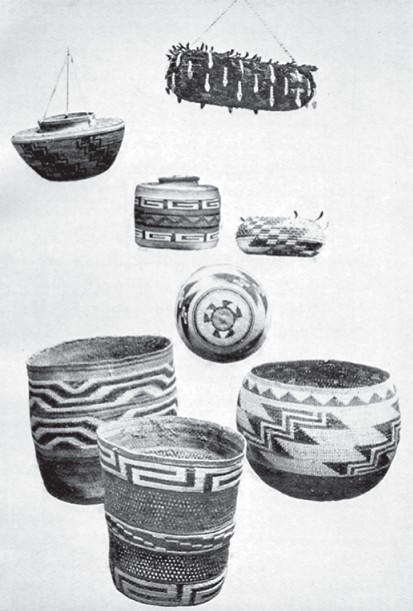

RARE POMA CEREMONIAL BASKET—Adorned with plumes of valley quail, wampum, shell, and feathers from the woodpecker's crown. MONO JAR. ALASKAN TREASURE BASKET—With snake rattles in cover. TWO ALASKAN CARRYING BASKETS. A SQUAW CAP—The design woven with stems of maiden-hair ferns. COOKING BASKET—Used by the Hupa Indians, California. It would be interesting, if space permitted, to trace the influence of basketry on design in general, to show the necessary adoption of straight lines, geometric patterns, through the exigencies of wicker weaving. The Indian imitates what she sees about her; she is a silent, profound student of nature which she strives to copy; but in order that natural objects may come within the limitations of basketry — the principal medium of expression — every object has to be conventionalized, its form modified. The square-shouldered human figures, the angular beasts and birds depicted by the ancient Egyptians, are not very different from the Indian's attempts to reproduce these same forms on ceremonial dance baskets, granaries, and plaques, with uncompromising willow and grasses. Given more plastic material through which to express art ideals, the Indian potter evolved graceful scrolls and curves from the almost universal design known as the Greek meander or rectilinear fret and its variants, which have been favorite themes with our Indians from time immemorial. The Indian is essentially artistic, not musical, like the African negro, and not literary, however masterful in the use of words in oratory. There is every reason to believe that our national art will receive new direction, a fresh impulse, from educated Indian Americans. The poor Indian, "whose untutored mindSees God in clouds and hears Him in the wind," has

recorded a wealth of such spiritual visions in her baskets alone:

scarcely one of them that does not contain a prayer. To how much of

the handiwork of modern civilized women, tutored or untutored,

could equal praise be given?

|

Web and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2010

(Return to Web Text-ures)