THE BIOGRAPHER

The

little green lizard on Solomon's wall

Basked

in the gold of a shimmering

noon,

Heard

the insistent, imperious call

Of

hautboy and tabor and loud bassoon,

When

Balkis passed by, with her alien grace,

And

the light of wonder upon her face,

To

sit by the King in his lofty hall, —

And

the little green lizard saw it all.

The

little green lizard on Solomon's wall

Waited

for flies the long day through,

While

the craftsmen came at the monarch's call

To

the task that was given each man to do,

And

the Temple rose with its cunning wrought gold,

Cedar

and silver, and all it could hold

In

treasure of tapestry, silk and shawl, —

And

the little green lizard observed it all.

The

little green lizard on Solomon's wall

Heard

what the King said to one alone,

Secrets

that only the Djinns may recall,

Graved

on the Sacred, Ineffable Stone.

And

yet, when the little green lizard was led

To

speak of the King, when the King was dead,

He

had only kept count of the flies on the wall, —

For

he was but a lizard, after all!

|

II

BASIL

THE SCRIBE

HOW

AN IRISH MONK IN AN ENGLISH ABBEY CAME TO STAND BEFORE KINGS

BROTHER

BASIL, of the scriptorium, was doing two things at once with the same

brain. He did not know whether any of the other monks ever indulged

in this or not. None of them showed any signs of it. The Abbot was

clearly intent, soul, brain and body, on the ruling of the community.

In such a house as this dozens of widely varied industries must be

carried on, much time spent in prayer, song and meditation, and

strict attention given to keeping in every detail the traditional

Benedictine rule. In many mediaeval Abbeys not all these things were

done. Rumor hinted that one Order was too fond of ease, and another

of increasing its estates. In the Irish Abbey where Brother Basil had

received his first education, little thought was given to anything

but religion; the fare was of the rudest and simplest kind. But in

this English Abbey everything in the way of clothing, tools,

furniture, meat and drink which could be produced on the lands was

produced there. Guests of high rank were often entertained. The

church, not yet complete, was planned on a magnificent scale. The

work of the making of books had grown into something like a large

publishing business. As the parchments for the writing, the leather

for the covers, the goose-quill pens, the metal clasps, the ink, and

the colors for illuminated lettering, were all made on the premises,

a great deal of skilled labor was involved. Besides the revenues from

the sale of manuscript volumes the Abbey sold increasing quantities

of wool each year. Under some Abbots this material wealth might have

led to luxury. But Benedict of Winchester held that a man who took

the vows of religion should keep them.

With

this Brother Basil entirely agreed. He desired above all to give his

life to the service of God and the glory of his Order. He was a

skillful, accurate and rapid penman. Manuscripts copied by him, or

under his direction, had no mistakes or slovenly carelessness about

them. The pens which he cut were works of art. The ink was from a

rule for which he had made many experiments. Every book was carefully

and strongly bound. Brother Basil, in short, was an artist, and

though the work might be mechanical, he could not endure not to have

it beautifully done.

The

Abbot was quite aware of this, and made use of the young monk's

talent for perfection by putting him in charge of the scriptorium. In

the twelfth century the monks were almost the only persons who had

leisure for bookmaking. They wrote and translated many histories;

they copied the books which made up their own libraries, borrowed

books wherever they could and copied those, over and over again. They

sold their work to kings, noblemen, and scholars, and to other

religious houses. The need for books was so great that in the

scriptorium of which Brother Basil had charge, very little time was

spent on illumination. Missals, chronicles and books of hymns

fancifully decorated in color were done only when there was a demand

for them. They were costly in time, labor and material.

Brother

Basil could copy a manuscript with his right hand and one half his

brain, while the other half dreamed of things far afield. He could

not remain blind to the grace of a bird's wing on its flight

northward in spring, to the delicate seeking tendrils of grapevines,

the starry beauty of daisies or the tracery of arched leafless

boughs. Within his mind he could follow the gracious curves of the

noble Norman choir, and he had visions of color more lustrous than a

sunrise.

Day

by day, year by year, the sheep nibbled the tender springing grass.

Yet the green sward continued to be decked with orfrey-work of many

hues buttercups, violets, rose-campion, speedwell, daisies defiant

little bright heads not three inches from the roots. His fancies

would come up in spite of everything, like the flowers.

But

would it always be so? Was he to spend his life in copying these

bulky volumes of theology and history the same old phrases, the same

authors, the same seat by the same window? And some day, would he

find that his dreams had vanished forever? Might he not grow to be

like Brother Peter, who had kept the porter's lodge for forty years

and hated to see a new face? This was the doubt in the back of his

mind, and it was very sobering indeed.

Years

ago, when he was a boy, he had read the old stories of the missionary

monks of Scotland and Ireland. These men carried the message of the

Cross to savage tribes, they stood before Kings, they wrought

wonders. Was there no more need for such work as theirs? Even now

there was fierce misrule in Ireland. Even now the dispute between

church and state had resulted in the murder of the Archbishop of

Canterbury on the steps of the altar. The Abbeys of all England had

hummed like bee-hives when that news came.

Brother

Basil discovered just then that the ink was failing, and went to see

how the new supply was coming on. It was a tedious task to make ink,

but when made it lasted. Wood of thorn-trees must be cut in April or

May before the leaves or flowers were out, and the bundles of twigs

dried for two, three or four weeks. Then they were beaten with wooden

mallets upon hard wooden tablets to remove the bark, which was put in

a barrel of water and left to stand for eight days. The water was

then put in a cauldron and boiled with some of the bark, to boil out

what sap remained. When it was boiled down to about a third of the

original measure it was put into another kettle and cooked until

black and thick, and reduced again to a third of its bulk. Then a

little pure wine was added and it was further cooked until a sort of

scum showed itself, when the pot was removed from the fire and placed

in the sun until the black ink purified itself of the dregs. The pure

ink was then poured into bags of parchment carefully sewn and hung in

the sunlight until dry, when it could be kept for any length of time

till wanted. To write, one moistened the ink with a little wine and

vitriol.

As

all the colors for illumination must be made by similar tedious

processes, it can be seen that unless there was a demand for such

work it would not be thrifty to do it.

Brother

Basil arrived just in time to caution the lay brother, Simon Gastard,

against undue haste. Gastard was a clever fellow, but he needed

watching. He was too apt to think that a little slackness here and

there was good for profits. Brother Basil stood over him until the

ink was quite up to the standard of the Abbey. But his mind meanwhile

ran on the petty squabblings and dry records of the chronicle that he

had just been copying. How, after all, was he better than Gastard? He

was giving the market what it wanted and the book was not worth

reading. If men were to write chronicles, why not make them vivid as

legends, true, stirring, magnificent stories of the men who moved the

world? Who would care, in a thousand years, what rent was paid by the

tenant farmers of the Abbey, or who received a certain benefice from

the King?

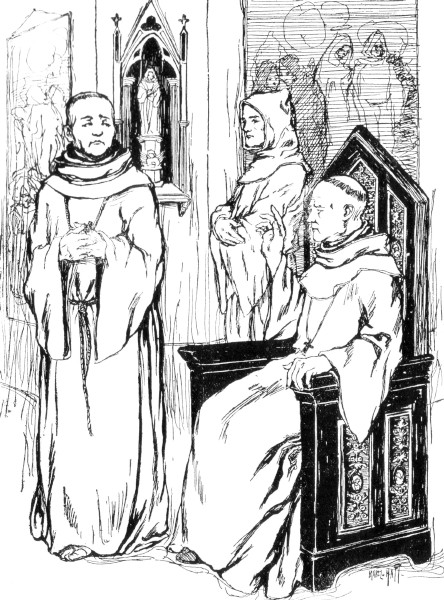

As

he turned from the sunlit court where the ink was amaking, he

received a summons to the Abbot's own parlor. He found that dignitary

occupied with a stout and consequential monk of perhaps forty-five,

who was looking bewildered, snubbed, and indignant. Brother Ambrosius

was most unaccustomed to admonitions, even of the mildest. He had a

wide reputation as a writer, and was indeed the author of the very

volume which Brother Basil was now copying. He seemed to know by

instinct what would please the buyers of chronicles, and especially

what was to be left out.

It

was also most unusual to see the Abbot thoroughly aroused. He had a

cool, indifferent manner, which made his rebukes more cutting. Now he

was in wrathful earnest.

"Ambrosius,"

he thundered, "there are some of us who will live to see Thomas

of Canterbury a Saint of the Church. But that is no reason why we

should gabble about it beforehand. You have been thinking yourself a

writer, have you? Your place here has been allowed you because you

are as a rule cautious even to timidity. Silence is always safe, and

an indiscreet pen is ruinous. The children of the brain travel far,

and they must not discuss their betters."

"Some

of us will live to see Thomas of Canterbury a Saint of the Church"

"Shall

we write then of the doings of hinds and swinkers?" asked the

historian, pursing his heavy mouth. "It seems we cannot write of

Kings and of Saints."

"You

may write anything in reason of Kings and of Saints when they are

dead," the Abbot retorted. "But if you cannot avoid

treasonable criticism of your King, I will find another historian. Go

now to your penance."

And

Brother Ambrosius, not venturing a reply, slunk out.

In

the last three minutes Brother Basil had seen far beneath the surface

of things. His deep-set blue eyes flamed. The dullness of the

chronicle was not always the dullness of the author, it seemed. The

King showed at best none too much respect for the Church, and his

courtiers had dared the murder of Becket. Surely the Abbot was right.

"Basil,"

his superior observed grimly, "in a world full of fools it would

be strange if some were not found here. It is the business of the

Church to make all men alike useful to God. Because the murder of an

Archbishop has set all Christendom a-buzz, we must be the more

zealous to give no just cause of offence. I do not believe that Henry

is guilty of that murder, but if he were, he would not shrink from

other crimes. In the one case we have no reason to condemn him; in

the other, we must be silent or court our own destruction. There are

other ways of keeping alive the memory of Thomas of Canterbury

besides foolish accusations in black and white. There may be

pictures, which the people will see, ballads which they will hear and

repeat the very towers of the Cathedral will be his monument.

"I

have sent for you now because there is work for you to do elsewhere.

The road from Paris to Byzantium may soon be blocked. The Emperor of

Germany is at open war with the Pope. Turks are attacking pilgrims in

the Holy Land. Soon it may be impossible, even for a monk, to make

the journey safely. The time to go is now.

"You

will set forth within a fortnight, and go to Rouen, Paris and

Limoges; thence to Rome, Byzantium and Alexandria. I will give you

memoranda of certain manuscripts which you are to secure if possible,

either by purchase or by securing permission to make copies. Get as

many more as you can. The King is coming here to-night in company

with the Archbishop of York, the Chancellor, a Prince of Ireland, and

others. He may buy or order some works on the ancient law. He desires

also to found an Abbey in Ireland, to be a cell of this house. I have

selected Cuthbert of Oxenford to take charge of the work, and he will

set out immediately with twelve brethren to make the foundation. When

you return from your journey it will doubtless be well under way. You

will begin there the training of scribes, artists, metal workers and

other craftsmen. It is true that you know little of any work except

that of the scriptorium, but one can learn to know men there as well

as anywhere. You will observe what is done in France, Lombardy and

Byzantium. The men to whom you will have letters will make you

acquainted with young craftsmen who may be induced to go to Ireland

to work, and teach their work to others. Little can be done toward

establishing a school until Ireland is more quiet, but in this the

King believes that we shall be of some assistance. I desire you to be

present at our conference, to make notes as you are directed, and to

say nothing, for the present, of these matters. Ambrosius may think

that you are to have his place, and that will be very well."

The

Abbot concluded with a rather ominous little smile. Brother Basil

went back to the scriptorium, his head in a whirl. Within a

twelvemonth he would see the mosaics of Saint Mark's in Venice, the

glorious windows of the French cathedrals, the dome of Saint Sophia,

the wonders of the Holy Land. He was no longer part of a machine.

Indeed, he must always have been more than that, or the Abbot would

not have chosen him for this work. He felt very humble and very

happy.

He

knew that he must study architecture above anything else, for the

building done by the monks was for centuries to come. Each brother of

the Order gathered wisdom for all. When a monk of distinguished

ability learned how to strengthen an arch here or carve a doorway

there, his work was seen and studied by others from a hundred towns

and cities. Living day by day with their work, the builders detected

weaknesses and proved step by step all that they did. Cuthbert of

Oxenford was a sure and careful mason, but that was all. The beauty

of the building would have to be created by another man. Glass-work,

goldsmith work, mosaics, vestments and books might be brought from

abroad, but the stone-work must be done with materials near at hand

and such labor as could be had. Brother Basil received letters not

only to Abbots and Bishops, but to Gerard the woodcarver of Amiens,

Matteo the Florentine artist, Tomaso the physician of Padua, Angelo

the glass-maker. He set all in order in the scriptorium where he had

toiled for five long years. Then, having been diligent in business,

he went to stand before the King.

Many

churchmen pictured this Plantagenet with horns and a cloven foot, and

muttered references to the old fairy tale about a certain ancestor of

the family who married a witch. But Brother Basil was familiar with

the records of history. He knew the fierce Norman blood of the race,

and knew also the long struggle between Matilda, this King's mother,

and Stephen. Here, in the plainly furnished room of the Abbot, was a

hawk-nosed man with gray eyes and a stout restless figure, broad

coarse hands, and slightly bowed legs, as if he spent most of his

days in the saddle. The others, churchmen and courtiers, looked far

more like royalty. Yet Henry's realm took in all England, a part of

Ireland, and a half of what is now France. He was the only real rival

to the German Emperor who had defied and driven into exile the Pope

of Rome. If Henry were of like mind with Frederick Barbarossa it

would be a sorry day indeed for the Church. If he were disposed to

contend with Barbarossa for the supreme power over Europe, the land

would be worn out with wars. What would he do? Brother Basil watched

the debating group and tried to make up his mind.

He

wrote now and then a paragraph at the Abbot's command. It seemed that

the King claimed certain taxes and service from the churchmen who

held estates under him, precisely as from the feudal nobles. The

Abbots and Bishops, while claiming the protection of English law for

their property, claimed also that they owed no obedience to the King,

but only to their spiritual master. Argument after argument was

advanced by their trained minds.

But

it was not for amusement that Henry II., after a day with some

hunting Abbot, falcon on fist, read busily in books of law. Brother

Basil began to see that the King was defining, little by little, a

code of England based on the old Roman law and customs handed down

from the primitive British village. Would he at last obey the Church,

or not?

Suddenly

the monarch halted in his pacing of the room, turned and faced the

group. The lightning of his eye flashed from one to another, and all

drew back a little except the Abbot, who listened with the little

grim smile that the monks knew.

"I

tell ye," said Henry, bringing his hard fist down upon the oaken

table, "Pope or no Pope, Emperor or no Emperor, I will be King

of England, and this land shall be fief to no King upon earth. I will

have neither two masters to my dogs, nor two laws to my realm. Hear

ye that, my lords and councilors'?"

|