HARPER'S

SONG

O

listen, good people in fair guildhall —

(Saxon

gate, Norman tower on the Roman wall)

A

King in forest green and an Abbot in gray

Rode

west together on the Pilgrims' Way,

And

the Abbot thought the King was a crossbowman,

And

the King thought the Abbot was a sacristan.

(On

White Horse Hill the bright sun shone,

And

blithe sang the wind by the Blowing Stone, —

O,

the bridle-bells ring merrily-sweet

To

the clickety-clack of the hackney's feet!)

Said

the King in green to the Abbot in gray,

"Shrewd-built

is yon Abbey as I hear say,

With

Purbeck marble and Portland stone,

Stately

and fair as a Caesar's throne."

"Not

so," quo' the Abbot, and shook his wise head, —

"Well-founded

our cloisters, when all is said,

But

the stones be rough as the mortar is thick,

And

piers of rubble are faced with brick."

(The

Saxon crypt and the Norman wall

Keep

faith together though Kingdoms fall, —

O,

the mellow chime that the great bells ring

Is

wooing the folk to the one true King!)

Said

the Abbot in gray to the King in green,

"Winchester

Castle is fair to be seen,

And

London Tower by the changeful tide

Is

sure as strong as the seas are wide."

But

the King shook his head and spurred on his way, —

"London

is loyal as I dare say,

But

the Border is fighting us tooth and horn,

And

the Lion must still hunt the Unicorn."

(The

trumpet blared from the fortress tower,

The

stern alarum clanged the hour,

O,

the wild Welsh Marches their war-song sing

To

the tune that the swords on the morions ring!)

The

King and the Abbot came riding down

To

the market-square of Chippenham town,

Where

wool-packs, wheatears, cheese-wych, flax,

Malmsey

and bacon pay their tax.

Quo'

the King to the Abbot, "The Crown must live

By

what all England hath to give."

"Faith,"

quoth the Abbot, "good sign is here

Tithes

are a-gathering for our clerkes' cheer."

(The

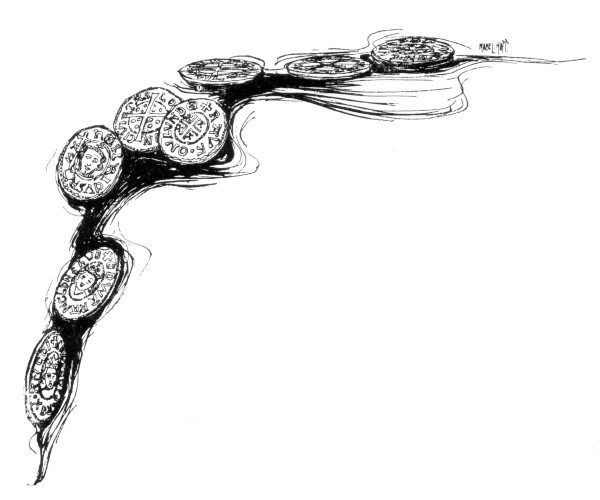

song of the Mint is the song I sing,

The

crown that the beggar may share with the King,

And

the clink of the coin rhymes marvelous well

To

castle, or chapel, or market-bell!)

|

IX

RICHARD'S

SILVER PENNY

HOW

RICHARD SOLD A WEB OF RUSSET AND MADE THE BEST OF A BAD BARGAIN

RICHARD

was going to market. He was rather a small boy to be going on that

errand, especially as he carried on his shoulder a bundle nearly as

big as he was. But his mother, with whom he lived in a little,

whitewashed timber-and-plaster hut at the edge of the common, was too

ill to go, and the Cloth Fair was not likely to wait until she was

well again.

The

boy could hardly remember his father. Sebastian Garland was a sailor,

and had gone away so long ago that there was little hope that he

would ever come back. Ever since Richard could remember they had

lived as they did now, mainly by his mother's weaving. They had a few

sheep which were pastured on the common, and one of the neighbors

helped them with the washing and shearing. The wool had to be combed

and sorted and washed in long and tedious ways before it was ready to

spin, and before it was woven it was dyed in colors that Dame Garland

made from plants she found in the woods and fields. She had been a

Highland Scotch girl, and could weave tyrtaine, as the people in the

towns called the plaids. None of the English people knew anything

about the different tartans that belonged to the Scottish clans, but

a woman who could weave those could make woolen cloth of a very

pretty variety of patterns. She worked as a dyer, too, when she could

find any one who would pay for the work, and sometimes she did

weaving for a farm-wife who had more than her maids could do.

Richard

knew every step of the work, from sheep-fleece to loom, and wherever

a boy could help, he had been useful. He had gone to get elder bark,

which, with iron filings, would dye black; he had seen oak bark used

to dye yellow, and he knew that madder root was used for red, and

woad for blue. His mother could not afford to buy the turmeric,

indigo, kermes, and other dyestuffs brought from far countries or

grown in gardens. She had to depend on whatever could be got for

nothing. The bright rich colors which dyers used in dyeing wool for

the London market were not for her. Yellow, brown, some kinds of

green, black, gray and dull red she could make of common plants,

mosses and the bark of trees. The more costly dyestuffs were made

from plants which did not grow wild in England, or from minerals.

Richard

was thinking about all this as he trudged along the lane, and

thinking also that it would be much easier for them to get a living

if it were not for the rules of the Weavers' Guild. This association

was one of the most important of the English guilds of the twelfth

century, and had a charter, or protecting permit, from the King,

which gave them special rights and privileges. He had also

established the Cloth Fair at Smithfield in London, the greatest of

all the cloth-markets that were so called. If any man did the guild

"any unright or disease" there was a fine of ten pounds,

which would mean then more than fifty dollars would to-day. Later he

protected the weavers still further by ordaining that the Portgrave

should burn any cloth which had Spanish wool mixed with the English,

and the weavers themselves allowed no work by candle-light. This

helped to keep up the standard of the weaving, and to prevent

dishonest dealers from lowering the price by selling inferior cloth.

As early as 1100 Thomas Cole, the rich cloth-worker of Reading, whose

wains crowded the highway to London, had secured a charter from Henry

I., this King's grandfather, and the measure of the King's own arm

had been taken for the standard ell-measure throughout the kingdom.

Richard

knew all this, because, having no one else to talk to, his mother had

talked much with him; and the laws of Scotland and England differed

in so many ways that she had had to find out exactly what she might

and might not do. In some of the towns the weavers' guilds had made a

rule that no one within ten miles who did not belong to the guild or

did not own sheep should make dyed cloth. This was profitable to the

weavers in the association, but it was rather hard on those who were

outside, and not every one was allowed to belong. The English weavers

were especially jealous of foreigners, and some of their rules had

been made to discourage Flemish and Florentine workmen and traders

from getting a foothold in the market.

Richard

had been born in England, and when he was old enough to earn a

living, he intended to repay his mother for all her hard and lonely

work for him. As an apprentice to the craft he could grow up in it

and belong to the Weavers' Guild himself some day, but he thought

that if there were any way to manage it he would rather be a trader.

He felt rather excited now as he hurried to reach the village before

the bell should ring for the opening of the market.

King's

Barton was not a very big town, but on market days it seemed very

busy. There was an irregular square in the middle of the town, with a

cross of stone in the center, and the ringing of this bell gave

notice for the opening and closing of the market. It was not always

the same sort of market. Once a week the farmers brought in their

cattle and sheep. On another day poultry was sold. In the season,

there were corn markets and grass markets, for the crops of wheat and

hay; and in every English town, markets were held at certain times

for whatever was produced in the neighborhood. Everybody knew when

these days came, and merchants from the larger cities came then to

buy or sell on other days they would have found the place half

asleep. In so small a town there was not trade enough to support a

shop for the sale of clothing, jewelry and foreign wares; but a

traveling merchant could do very well on market days.

When

Richard came into the square the bell had just begun to ring, and the

booths were already set up and occupied. His mother had told him to

look for Master Elsing, a man to whom she had sometimes sold her

cloth, but he was not there. In his stall was a new man. There was

some trade between London and the Hanse, or German cities, and

sometimes they sent men into the country to buy at the fairs and

markets and keep an eye on trade. Master Elsing had been one of

these, and he had always given a fair price. The new man smiled at

the boy with his big roll of cloth, and said, "What have you

there, my fine lad?"

Richard

told him. The man looked rather doubtful. "Let me see it,"

he said.

The

cloth was a soft, thick rough web with a long furry nap. If it was

made into a cloak the person who wore it could have the nap sheared

off when it was shabby, and wear it again and shear it again until it

was threadbare. A man who did this work was called a shearman or

sherman. The strange merchant pursed his lips and fingered the cloth.

"Common stuff," he said, "I doubt me the dyes will not

be fast color, and it will have to be finished at my cost. There is

no profit for me in it, but I should like to help you I like manly

boys. What do you want for it?"

Richard

named the price his mother had told him to ask. There was an empty

feeling inside him, for he knew that unless they sold that cloth they

had only threepence to buy anything whatever to eat, and it would be

a long time to next market day. The merchant laughed. "You will

never make a trader if you do not learn the worth of things, my boy,"

he said good-naturedly. "The cloth is worth more than that. I

will give you sixpence over, just by way of a lesson."

Richard

hesitated. He had never heard of such a thing as anybody offering

more for a thing than was asked, and he looked incredulously at the

handful of silver and copper that the merchant held out. "You

had better take it and go home," the man added. "Think how

surprised your mother will be! You can tell her that she has a fine

young son Conrad Waibling said so."

Richard

still hesitated, and Waibling withdrew the money. "You may ask

any one in the market," he said impatiently, "and if you

get a better price than mine I say no more."

"Thank

you," said Richard soberly, "I will come back if I get no

other offer."

He

took his cloth to the oldest of the merchants and asked him if he

would better Waibling's price, but the man shook his head. "More

than it is worth," he said. "Nobody will give you that, my

boy." And from two others he got the same reply. He went back to

Waibling finally, left the cloth and took his price.

He

had never seen a silver penny before. It had a cross on one side and

the King's head on the other, as the common pennies did; it was

rather tarnished, but he rubbed it on his jacket to brighten it. He

thought he would like to have it bright and shining when he showed it

to his mother. All the time that he was sitting on a bank by the

roadside, a little way out of the town, eating his bread and cheese,

he was polishing the silver penny. A young man who rode by just then,

with a black-eyed young woman behind him, reined in his horse and

looked down with some amusement. "What art doing, lad?" he

asked.

"It's

my silver penny," said Richard. "I wanted it to be fine and

bonny to show mother."

"Ha!"

said the young man. "Let's see." Richard held up the penny.

"Who gave you that, my boy?"

"Master Waibling the

cloth-merchant," said Richard, and he told the story of the

bargain.

The

young man looked grave. "Barbara," he said to the girl,

"art anxious to get home? Because I have business with this same

Waibling, and I want to find him before he leaves the town."

The

girl smiled demurely. "That's like thee, Robert," she said.

"Ever since I married thee, — and long before, it's been the

same. I won't hinder thee. Leave me at Mary Lavender's and I'll have

a look about her garden."

The

two rode off at a brisk pace, and Richard saw them halt at a gate not

far away, and while the girl went in the man mounted his horse again

and came back. "Jump thee up behind me, young chap," he

ordered, "and we'll see to this. The silver penny is not good.

He probably got it in some trade and passed it off on the first

person who would take it. Look at this one."

Edrupt

held up a silver penny from his own purse.

"I

didn't know," said Richard slowly. "I thought all pennies

were alike."

"They're

not — but until the new law was passed they were well-nigh

anything you please. You see, this penny he gave you is an old one.

Before the new law some time, when the King needed money very badly,

— in Stephen's time maybe — they mixed the silver with lead to

make it go further. That's why it would not shine. And look at this."

He took out another coin. "This is true metal, but it has been

clipped. Some thief took a bag full of them probably, clipped each

one as much as he dared, passed off the coins for good money, and

melted down the parings of silver to sell. Next time you take a

silver penny see that it is pure bright silver and quite round."

By

this time they were in the market-place. Edrupt dismounted, and gave

Richard the bridle to hold; then he went up to Waibling's stall, but

the merchant was not there.

"He

told me to mind it for him," said the man in the next booth. "He

went out but now and said he would be back in a moment."

But

the cloth-merchant did not come back. The web of cloth he had bought

from Richard was on the counter, and that was the only important

piece of goods he had bought. Quite a little crowd gathered about by

the time they had waited awhile. Richard wondered what it all meant.

Presently Edrupt came back, laughing.

"He

has left town," he said to Richard. "He must have seen me

before I met you. I have had dealings with him before, and he knew

what I would do if I caught him here. Well, he has left you your

cloth and the price of the stuff, less one bad penny. Will you sell

the cloth to me? I am a wool-merchant, not a cloth-merchant, but I

can use a cloak made of good homespun."

Richard

looked up at his new friend with a face so bright with gratitude and

relief that the young merchant laughed again. "What are you

going to do with the penny?" he asked the boy, curiously.

"I'd

like to throw it in the river," said Richard in sudden wrath.

"Then it would cheat no more poor folk."

"They

say that if you drop a coin in a stream it is a sign you will

return," said Edrupt, still laughing, "and we want neither

Waibling nor his money here again. Suppose we nail it up by the

market-cross for a warning to others'? How would that be?"

This

was the beginning of a curious collection of coins that might be

seen, some years later, nailed to a post in the market of King's

Barton. There were also the names of those who had passed them, and

in time, some dishonest goods also were fastened up there for all to

see. When Richard saw the coin in its new place he gave a sigh of

relief.

"I'll

be going home now," he said. "Mother's alone, and she will

be wanting me."

"Ride

with me so far as Dame Lavender's," said the wool-merchant

good-naturedly. "What's thy name, by the way?"

"Richard

Garland. Father was a sailor, and his name was Sebastian," said

the boy soberly. "Mother won't let me say he is drowned, but I'm

afraid he is."

"Sebastian

Garland," repeated Edrupt thoughtfully. "And so thy mother

makes her living weaving wool, does she?"

"Aye,"

answered Richard. "She's frae Dunfermline last, but she was born

in the Highlands."

"My

wife's grandmother was Scotch," said Edrupt absently. He was

trying to remember where he had heard the name Sebastian Garland. He

set Richard down after asking him where he lived, and took his own

way home with Barbara, his wife of a year. He told Barbara that the

town was well rid of a rascal, but she knew by his silence thereafter

that he was thinking out a plan.

"Some

day," he spoke out that evening, "there'll be a law in the

land to punish these dusty-footed knaves. They go from market to

market cheating poor folk, and we have no hold on them because we

cannot leave our work. But about this lad Richard Garland, Barbara,

I've been a-thinking. What if we let him and his mother live in the

little cottage beyond the sheepfold? The boy could help in tending

the sheep. If they've had sheep o' their own. they'll know how to

make 'emselves useful, I dare say. And then, when these foreign

fleeces come into the market, the dame could have dyes and so on, and

we should see what kind o' cloth they make."

This

was the first change in the fortunes of Richard Garland and his

mother. A little more than a year later Sebastian Garland, now

captain of Master Gay's ship, the Rose-in-June, of London, came into

port and met Robert Edrupt. On inquiry Edrupt learned that the

captain had lost his wife and son many years before in a town which

had been swept by the plague. When he heard of the Highland-born

woman living in the Longley cottage, he journeyed post-haste to find

her, and discovered that she was indeed his wife, and Richard his

son. By the time that Richard was old enough to become a trader, a

court known as the Court of Pied-poudre or Dusty Feet had been

established by the King at every fair. Its purpose was to prevent

peddlers and wandering merchants from cheating the folk. The common

people got the name "Pie-powder Court," but that made it

none the less powerful. King Henry also appointed itinerant justices

traveling judges to go about from place to place and judge according

to the King's law, with the aid of the sheriffs of the neighborhood

who knew the customs of the people. The general instructions of these

courts were that when the case was between a rich man and a poor man,

the judges were to favor the poor man until and unless there was

reason to do otherwise. The Norman barons, coming from a country in

which they had been used to be petty kings each in his own estate,

did not like this much, but little the King cared for that. Merchants

like young Richard Garland found it most convenient to have one law

throughout the land for all honest men. Remembering his own hard

boyhood, Richard never failed to be both just and generous to a boy.

|