|

SONG OF THE TAPESTRY WEAVERS

All

among the furze-bush, round the crystal dewpond,

Feed the

silly sheep like a cloud upon

the down.

Come

safely home to croft, bear fleeces white and soft,

Then

we'll send the wool-wains to fair

London Town.

All

in the dawnlight, white as a snowdrift

Lies the

wool a-waiting the spindle

and the wheel.

Sing,

wheel, right cheerily, while I pace merrily, —

Knot by

knot the thread runs on the

busy reel.

All

in the sunshine, gay as a garden,

Lie the

skeins for weaving, the blue

and gold and red.

Fly,

shuttle, merrily, in and out cheerily,

Making

all the woof bright with a

rainbow thread.

All

in the noontide, wend we to market, —

Hear the

folk a-chaffering like

jackdaws up and down.

Master,

give ear to me, here's cloth for you to see.

Fit for

a canopy in fair London Town.

All

in the twilight sweet with the hearth-smoke,

Homeward

we go riding while the vesper

bells ring,

Southdown

or Highland Scot, Fleming or Huguenot,

Weaving

our tapestries we shall serve

our King!

|

XVI

LOOMS

IN MINCHEN LANE

HOW

CORNELYS BAT, THE FLEMISH WEAVER, BEFRIENDED A BLACK SHEEP AND SAVED

HIS WOOL

IT

was in the early springtime, when lambs are frisking like rabbits

upon the tender green grass, and all the land is like a tapestry of

blue and white and gold and pink and green. Robert Edrupt, as he rode

westward from London on his homeward way, felt that he had never

loved his country quite so well as now. He had gone with a flock of

English sheep to northern Spain, and come back in the same ship with

the Spanish jennets which the captain took in exchange. On one of

those graceful half-Arabian horses he was now riding, and on another,

a little behind him, rode a swarthy, black-haired and black-eyed

youngster in a sheepskin tunic, who looked about him as if all that

he saw were strange.

In

truth Cimarron, as they called him, was very like a wild sheep from

his native Pyrenees, and Edrupt was wondering, with some amusement

and a little apprehension, what his grandmother and Barbara would

say. The boy had been his servant in a rather dangerous expedition

through the mountains, and but for his watchfulness and courage the

English wool-merchant might not have come back alive. Edrupt had been

awakened between two and three in the morning and told that robbers

were on their trail, and then, abandoning their animals, Cimarron had

led him over a precipitous cliff and down into the next valley by a

road which he and the wild creatures alone had traveled. When the

horses were led on shipboard the boy had come with them, and London

was no place to leave him after that.

They

rode up the well-worn track into the yard of Longley Farm, and

leaving the horses with his attendant, Edrupt went to find his

family. Dame Lysbeth was seated in her chair by the window, spinning,

and would have sent one of the maids to call the mistress of the

house, but Edrupt shook his head. He said that he would go look for

Barbara himself.

He

found her kneeling on the turf tending a motherless lamb, and it was

a good thing that the lamb had had nearly all it could drink already,

for when Barbara looked up and saw who was coming the rest of the

milk was spilled. She looked down, laughing and blushing, presently,

at the hem of her russet gown.

"Sheep

take a deal o' mothering," she explained, "well-nigh as

much as men. Come and see the new-born lambs, Robert, will 'ee?"

Robert

stroked the head of the old sheep-dog that had come up for his share

of petting. "Here is a black sheep for thee to mother,

sweetheart," he said with a laugh. "He's of a breed that is

new in these parts."

Barbara

looked at the rough, unkempt young stranger, with surprise but no

unkindness in her eyes. She was not easily upset, and however wild he

looked, the new-comer had been brought by Robert, and that was all

that concerned her.

"Where

did tha find him, and what's his name?" she inquired.

Edrupt

laughed again, in proud satisfaction this time; he might have known

that Barbara would behave just in that way. He explained, and

Cimarron was forthwith shown a corner of a loft where he might sleep,

and introduced to Don the collie as a shepherd in good standing. He

and the sheepdog seemed to understand each other almost at once, and

though one was almost as silent as the other, they became excellent

comrades.

Besides

the sheep, Cimarron seemed interested in but one thing on the farm,

and that was the old loom which had belonged to Dame Garland and

still stood in the weaving-chamber, where he slept. Dame Lysbeth,

rummaging there for some flax that she wanted, found the boy sitting

on the bench with one bare foot on the treadle, studying the workings

of the clumsy machine. It was a "high-warp" loom, in which

the web is vertical, and in the loom-chamber where Barbara's maids

spun and wove, Edrupt had set up a Flemish "low-warp" loom

with all the latest fittings. Into that place the herd-boy had never

ventured. But Dame Lysbeth saw with surprise that he seemed to

understand this loom quite well. When he was asked, he said that he

had seen weaving done on such a loom in his country.

"Robert

will be surprised," said Barbara thoughtfully. "Who ever

saw a lad like that who cared about weaving?"

But

Edrupt was not as mystified as the women were. He thought it quite

possible that the dark young stranger might have come of some Eastern

race which had made weaving an art beyond anything the West could do.

"I think," he said one morning, "that I will take him

to London and let him try what he can do in Cornelys Bat's factory."

Cornelys

Bat was a Flemish weaver who had come to London some months before

and set up his looms in an old wool-storeroom outside London Wall. He

was a very skillful workman, but Flanders had weavers enough to

supply half Europe with clothing, and his own town of Arras was

already known for its tapestries. The Lowlands were overcrowded, and

there was not bread enough to go around. Edrupt, whom he had known

for several years, helped him to settle himself in England, and he

had met with almost immediate success. Now he had with him not only

his old parents, a younger brother and sister and an aunt with her

two children, but three neighbors who also found life hard in

populous Flanders. He felt that he had done well in following

Edrupt's advice, "When the wool won't come to you, go where the

wool is." He was a square-built, placid, light-haired man with a

stolid expression that sometimes misled people. When Edrupt came to

him with a strange new apprentice, he readily consented to give the

boy a chance. It was the only chance that there was, for the Weavers'

Guild would not have had him.

After

a while Cimarron, or Zamaroun as the other 'prentices called him, was

promoted from porter to draw-boy, as the weaver's assistant was

termed. This work did not need skill, exactly, but it did demand

strength and close attention. The boy from the Pyrenees was as strong

as a young ox, and he was never tired of watching the work and seeing

exactly how it was done. His silent, quick strength suited Cornelys

Bat. Weaving is work which needs the constant thought of the weaver,

especially when the work is tapestry, and just at present the

Flemings had secured an order for a set of tapestries for one of the

King's country houses. Henry II. was so continually traveling that

the King of France once petulantly observed that he must fly like a

bird through the air to be in so many places during the year. He had

a way of mixing sport with state affairs, and a week spent in some

palace like Woodstock or Clarendon might be divided evenly between

his lawyers and his hunting-dogs. It is also said of him that he

never forgot a face or a fact once brought to his notice. Perhaps he

learned more on his hunting trips than any one imagined.

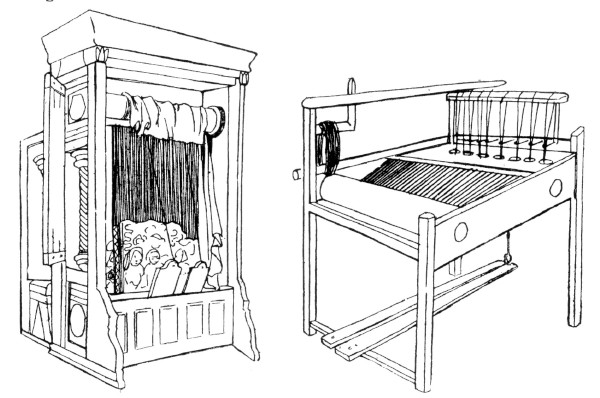

HIGH-WARF

LOOM

LOW-WARF LOOM

The

tapestry weaving was far more complex and difficult than anything

done by Barbara Edrupt's maids. The loom used by the Flemings was a

"low-warp" loom, in which the web is horizontal. When the

heavy timbers were set up they were mortised together, that is, a

projection in one fitted into a hollow in another, dovetailing them

together without nails. Wooden pegs fitted into holes, and thus the

frame, in all its parts, could be taken to pieces and carried from

place to place on pack-horses if necessary. An ordinary loom was

about eight feet long and perhaps four feet wide, the web usually

being not more than a yard wide, and more commonly twenty-three or

four inches. Broadcloth was woven in those days, but not very

commonly, for it needed a specially constructed loom and two weavers,

one for each side, because of the width of the cloth. In tapestry

weaving the picture was made in strips, as a rule, and sewed

together.

The

idea of tapestry weaving in the early part of the Middle Ages was to

tell a story. Few colors were used, and instead of making one large

picture, which would have been very difficult with the looms then in

use, the tapestries were made in sets, in which a series of pictures

from some legends or chronicle could be shown. When in place, they

were wall-coverings hung loosely from great iron hooks over which

rings were slipped, or hangings for state beds, or sometimes a strip

of tapestry was hung above the carved choir-stalls of a church,

horizontally, to add a touch of color to the gray walls. When a court

moved, or there was a festival day in the church, these woven or

embroidered hangings could be taken from one place to another. Many

tapestries were embroidered by hand, which was easier for the

ordinary woman than weaving a picture, but took far more time. Kings

and noblemen who had money to spend on such things would order sets

of tapestry woven by such skilled workmen as Cornelys Bat and his

Flemings, or the monks of Saumur in France, or the weavers of

Poitiers. In Sicily, these hangings were often made of silk, for silk

was already made there. Gold and silver thread was used sometimes,

both in weaving and embroidery. Wool, however, was very satisfactory,

not only because it was less costly than silk, but because it took

dye well and made a web of rich soft colors. It was this which had

drawn Robert Edrupt into Flanders to see what the weavers there were

about, what sort of wool they used, and what the outlook was for

their work. In Cornelys Bat he had found a man who could tell him

very nearly all that there was to know about weaving.

Yet

weaving is a craft of so many possibilities and complexities that a

man may spend his whole life at it and still feel himself only a

learner. The master weaver liked Cimarron because the boy never

chattered, but kept his whole mind on his work. When Cornelys was

revolving some new combination or design in his head, his drawboy was

as silent as the weaver's beam, and the whirr and clack of the loom

were the only sounds in the place.

The

weaver at such a loom sat at one end on a little board, with the

heavy roller or weaver's beam on which the warp, the lengthwise

thread, was fastened in front of him. At the far end of the frame was

another roller, the warp being stretched taut between the two. As the

work progressed the web was rolled up gradually toward the weaver,

and the pattern, if there was one, lay under the warp and was rolled

up on a separate roller. Every skilled weaver had a number of simple

patterns in his head, as a knitter has, but for a tapestry picture a

pattern was drawn and colored on parchment ruled in squares, and a

duplicate pattern made without the color, showing all the arrangement

of the threads and used in "gating" as the arrangement of

the warp in the beginning was called. Every weaver had his own way of

gating, and his own little tricks of weaving. It was a craft that

gave a chance for any amount of ingenuity.

In

plain, "tabby" or "taffety" weaving, the weft or

woof, the crosswise thread, went in and out exactly as in darning,

and the two treadles underneath the web, worked by the feet, lifted

alternately the odd threads and the even threads, the weaver tossing

the shuttle from hand to hand between them. At each stroke of the

shuttle the swinging beam, or batten, beat up the weft to make a

close, firm, even weave. The shuttle, made of boxwood and shaped like

a little boat, held in its hollow the "quill" or bobbin

carrying the weft. When all the "yarn," as thread for

weaving was always called, was wound off, the weaver fastened on the

end of the next thread with what is even now called a "weaver's

knot." As the side of the web toward him was the wrong side of

the cloth, no knot was allowed to show on the right side.

In

brocaded, figured or tapestry weaving, leashes or loops called

heddles were hung from above and lifted whatever part of the warp

they were attached to. For example, three threads out of ten in the

warp could be lifted by one group of heddles with one motion of the

treadle, the heddles being grouped or "harnessed" to make

this possible. It can be seen that in weaving by hand a tapestry with

perhaps forty or fifty figures and animals, besides flowers and

trees, the most convenient arrangement of the heddles called for

brains as well as skill of hand in the weaver who did the work. The

drawboy's work was to pull each set of cords in regular order forward

and downward. These cords had to raise a weight of about thirty-six

pounds, which the boy must hold for perhaps a third of a minute while

the ground was woven. He was in a way a part of the machine, but a

part which had a brain.

A

ratchet on the roller which held the finished web kept it from

slipping back and held the warp stretched firm at that end, and in

some looms there was a ratchet on the other roller as well. But

Cornelys Bat preferred weights at the far end of the warp. These

allowed the warp to give a tiny bit at every blow of the batten and

then drew it instantly taut, no matter how heavy the box was made.

"This kindly giving," explained the weaver, "preventeth

the breaking of the slender threads. No law may be kept too straitly

and no thread drawn too strictly. That is a part of the craft."

Cornelys

may have been thinking of something more than weaving when he made

that observation. The quiet tapissiers of Arras had caused an uproar

in the Guild of London Weavers. A few cool heads advised the others

to live and let live. The Flemings would be good English folk in

time, and whatever they knew would help the craft in the future. But

others, forgetting that they had refused to let their sons serve

apprenticeship to Cornelys Bat when he came, railed at him for taking

Flemings, Gascons, Florentines and even a vagabond from nobody knew

where, into his employ.

"We

will have no black sheep in our fold," vociferated the leader of

this faction, a keen-faced, tow-headed man of middle age. "These

foreigners will ruin the craft."

"Tut,

tut," protested Martin Byram, "I have heard Master Cole of

Reading say that thy grandfather, his 'prentice boy, was a Swabian,

Simon. And he brought no craft to England."

There

was a laugh, for everybody knew that the superior skill of the

Flemings was one main cause of their success in the market. Some of

the weavers even had the insight to see that so far from taking work

away from any English weaver, they were thus far doing work which

would have gone abroad to find them if they had not been here, and

the gold paid them was kept and spent in London markets.

For

all that, the feeling against the Flemings grew and spread, and might

have broken out into open violence if they had not been working on

the King's tapestries. Nobody felt like interfering with them until

that job was done, for the King might ask questions, and not like the

answers.

How

much of all this Cornelys Bat knew, no one could tell. Cimarron

watched him, but the broad, thoughtful face was placid as usual. One

day, however, the dark young apprentice was set upon in the street,

where he had gone on an errand, by a crowd of other lads who nearly

tore the clothes off his back. They had not reckoned on effectual

fighting strength in this foreign youth, and they found that even a

black sheep can be dangerous on occasion. The threats which they

muttered set the boy's mountain-bred senses on the alert, and he went

back to the master weaver with the information that as soon as the

King's tapestries were finished the looms and their shelter would be

burned over their heads.

"I

hid in the loft and heard," said Cimarron earnestly. "They

are evil men here, master."

The

Fleming frowned slightly and balanced the beam of his loom — he was

about to begin the last panel — thoughtfully in his hand. "So

it seems," he said. "Well, we will finish the tapestries as

early as may be."

One

of the weavers saw lights in the Flemish loom-rooms that night, and

reported that the strangers were working by candle-light, contrary to

the law of the Guild — to which they did not belong. But Cornelys

Bat was gathering together the work already done, and he and Cimarron

and two of the other men carried it before morning to the warehouse

of Gilbert Gay, the merchant, where it would be safe. They also took

there certain bales of fine wool, dyes, and some household goods, and

all this was loaded the next day on a boat and sent up the Thames to

a point above London, where Robert Edrupt's pack-horses took it to

King's Barton.

"It

is no use to try to fight the entire Guild," said Edrupt

ruefully. "You had best come to our village and make your home

there. When this has blown over you may come back to London."

"If

I were alone I would not budge," said the Fleming with a

sternness in his blue eyes. "But there are the old folk and the

little ones. We have left our own land and come where the wool was;

it is now time for the work to come to us."

"I

will warrant you it will," said Master Gay. "But are you

going to leave your looms for them to burn?"

"Not

quite," said Cornelys Bat, grimly.

The

mob came just after nightfall of the day after the women and

children, with the rest of the household goods, had gone on their way

to a new home. It was not a very well organized crowd, and was armed

with clubs, pikes, and torches mainly. It found to its astonishment

that the timbers of a loom, heavy and well seasoned, may make

excellent weapons, and that the arm of a weaver is not feeble nor his

spirit weak. It was no part of the plan of Cornelys Bat to leave the

buildings of Master Gay undefended, and the determined, organized

resistance of the Flemings repelled the attack. The next day it was

found that the weavers had gone, and their quarters were occupied by

some of Master Gay's men who were storing there a quantity of this

year's fleeces. Meanwhile the Flemings had settled in the little road

that ran past the nunnery at King's Barton and was called Minchen

Lane.

|