| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2016 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

THE VOICE

OF THE BELL WHEN Tai

Jo, the great general and first King of Korea, founded a new dynasty,

he moved

the capital near the great river Han and resolved to build a mighty

city called

Han Yang, or the Castle on the Han. It was to have a high wall around

it and

lofty gates on each side. However, the people commonly called the city

Seoul,

or Capital. All the roads in the kingdom lead to it. Happy was

he when the workmen, in digging for the foundations of the East Gate,

came upon

a bell. It was a lucky omen and they carried it at once to the king. He

had it

suspended over the entrance to his palace and there it still hangs. But such a

bell could only tinkle, while King Tai Jo wanted one that would boom

loud and

long. He was especially anxious about this, for in Silla, once a rival

state,

there had hung for centuries one of the biggest bells in the world and

Tai Jo

wanted one that excelled even that famed striker of the hours. He would

have

even a larger bell to hang in the central square in the heart of Seoul,

that

could be heard by every man, woman and child in the city. After that,

it must

be able to flood miles of hill and valley with its melody. By this

sound the

people would know when to get up, cook their breakfast, sit down to

supper, or

go to bed. On special occasions his subjects would know when a king's

procession was passing, or a royal prince or princess was being

married. It

would sound out a dirge when, His Majesty being dead, all the land must

mourn

and the people wear white clothes for three years and Korea become the

land of

mourners. The guardian spirit of the city would have its home in the

bell. Word was

sent out by messengers who rode on big horses, little ponies, donkeys

and bulls

to all the provinces, publishing the king's command to all governors,

magistrates and village-heads to collect the copper and tin to make the

bronze

metal. The bell was to stand ten feet above the ground and be eight

feet

across; that is, as high and wide as a Korean bedroom. On the top,

forming the

framework, by which the bell was to be hung, were to be two terrible

looking

dragons. Weighing so many tons that it would balance five hundred fat

men on a

seesaw, only heavy beams made of whole tree-trunks could hold it in the

belfry,

which must be strong enough to stand the shaking when the monster was

rung. It

had no clapper inside, but without, swung by heavy ropes from pulleys

above,

was a long log. This men pulled back and then let fly, striking the

boss on the

bell's surface. This awoke the music of the bell, making it toll, boom,

rumble,

growl, hum, croak, or roll sweet melody, according as the old bellman

desired. So the

procession of bullock carts on the roads to Seoul creaked with the

ingots of

copper. Many a donkey had swallowed gallons of bean soup at the inn

stables

before he dropped his load of metal in the city, while hundreds of

bulls

bellowed under their weight of the brushwood and timber piled on their

backs to

feed the furnaces, which were to melt the alloy for the casting of the

mighty

bell. Deep was

the pit dug to hold the core and mould, and hundreds of fire-clay pots

and

ladles were made ready for use when the red-hot stream should be ready

to flow.

All the boys in Seoul were waiting to watch the fire kindle, the smoke

rise,

the bellows roar, the metal liquify and the foreman give the signal to

tap. When the

fire-imp in the volcano heard of what was going on, he was awfully

jealous, not

thinking ever that common men could handle so much metal, direct

properly such

roaring flames, and cast so big a bell. He snorted at the idea that King Tai Jo's men could

beat the bells that hung in China's

mighty temples or in Silla's pagodas. But when

there was not yet enough and the copper collectors were still at their

work,

one of them came to a certain village and called at a house where lived

an old

woman carrying a baby boy strapped to her back. She had no coin, cash,

metal,

or fuel to give, but was quite ready to offer either herself or the

baby. In a

tone that showed her willingness, she said: "May

I give you this boy?" The

collector paid no attention to her, but passed on, taking nothing from

the old

woman. When in Seoul, however, he told the story. Thus it came to pass

that many

heard of the matter and remembered it later. So when

all was ready, the fire-clay crucibles were set on the white-hot coals.

The

blast roared until the bronze metal turned to liquid. Then, at the word

of the

master, the hissing, molten stream ran out and filled the mould.

Patiently

waiting till the metal cooled, alas they found the bell cracked. The

casting was raised by means of heavy tackle, erected at great expense

on the

spot, and the bell was broken up into bits by stalwart blacksmiths,

wielding heavy

hammers. Then a second casting was made, but again, when cool, it was

found to

be cracked. Three

separate times this happened, until the price of a palace had been paid

for

work, fuel, and wages, and yet there was no bell. King Tai Jo was in

despair.

Yet, instead of crying or pulling his topknot, or berating the

artisans, who

had done the best they could, he offered a large reward to any one who

could

point out where the trouble lay, or show what was lacking, and thus

secure a

perfect casting. Thereupon out stepped a workman from the company, who

told the

story of the old woman and said that the bell would crack after every

cooling

unless her proposal was accepted. Anyway, he said, the hag was a

sorceress, and

if the child were not a real human being no harm could be done. So the

baby boy was sent for and, when the liquid metal had half filled the

pit, was

thrown into the mass. There was some feeling about "feeding a child to

the

fire demon," but when they hoisted the cooled bell up from the mould,

lo,

the casting was a perfect success and every one apparently forgot about

the

human life that had entered the bell. Soon with file and chisel, the

great work

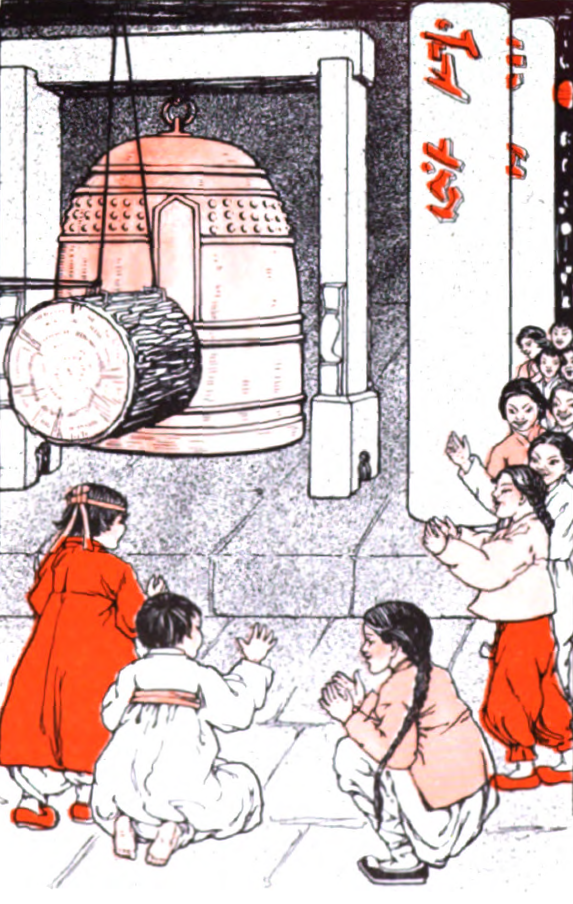

was finished. The hanging ceremonies were very impressive when the bell

was put

in place on the city's central square, where the broad streets from the

South

Gate and those looking to sunrise and sunset met together. Suspended by

heavy

iron links from the staple on a stout timber frame, the bell's mouth

was

exactly a foot above ground. Then, around and over it, was built the

belfry.

The names of the chief artisans who cast the bell and of the royal

officers who

superintended the hanging ceremonies were engraved on the metal. It was

decided, however, not to strike the bell until it was fully housed and

the

sounder or suspended log of wood, as thick as the mast of a ship, was

made

ready to send forth the initial boom. Meanwhile

tens of thousands of people waited to hear the first music of the bell.

Every

one believed it to be good luck and that they would live the longer for

it. The

boys and girls could hardly go to bed for listening, and some were

afraid they

might be asleep when it boomed. The little folks, whose eyes were

usually fast

shut at sunset, begged hard to stay up that night until they could hear

the

bell, but some fell asleep, because they could not help it, and their

eyes

closed before they knew it. "What

shall the name of the bell be, your Majesty?" asked a wise counselor. "Call

it In Jung," said King Tai Jo. "That means 'Man Decides,' for every

night, at nine o'clock, let every

man or boy decide to go to bed. Except magistrates, let not one male

person be

found in the street on pain of being paddled. From that hour until

midnight the

women shall have the streets to themselves to walk in." The royal law

was

proclaimed by trumpeters and it was ordained also that every morning

and

evening, at sunrise and sunset, the band of music should play at the

opening

and shutting of the city gates. So In

Jung, or "Masculine Decision," is the bell's name to this day. But as yet

the bell was silent. It had not spoken. When it did sound, the Seoul

people

discovered that it was the most wonderful bell ever cast. It had a

memory and a

voice. It could wail, as well as sing. In fact, some to this day

declare it can

cry; for, whether in childhood, youth, middle or old age, in joy or

gladness,

the bell expresses their own feelings by its change of note, lively or

gay, in

warning or congratulation. At nine

o'clock in the first night of the seventh moon —

the month of the Star Maiden of the Loom and the Ox-boy with his train

of attendants, who stand on opposite sides of the River of Heaven and

cross

over on the bridge of birds, the great bell of Seoul was to be sounded.

All the

men were in their rooms ready to undress and go to bed at once, while

all the

women, fully clothed in their best, were on the door-steps ready, each

with her

lantern in hand, for their promenade outdoors. Four

strong men seized the rope, pulled back the striking log a whole yard's

distance and then let fly. Back bounded the timber and out gushed a

flood of

melody that rolled across the city in every direction, and over the

hills,

filling leagues of space with melody. All the children clapped their

hands and

danced with joy. They knew they would live long, for they had heard the

sweet

bell's first music. The old people smiled with joy. But what

was the surprise of the adult folks to hear that the bell could talk. Yes, its sounds actually

made a sentence. "Mu-u-u-ma-ma-ma-la-la-la-la-la-la—"

until it ended like a baby's cry. Yes! There was no mistake about it.

This is

what it said: "My

mother's fault. My mother's fault." And to

this day the mothers in Seoul, as they clasp their darlings to their

bosoms,

resolve that it shall be no fault of theirs if these lack love or care.

They

delight in their little ones more, and lavish on

them a tenderer affection because they hear the great bell talk,

warning

parents to guard what Heaven has committed to their care. |