CHAPTER IV

Jimmy ran as hard as he

could in the direction

of the firing.

When he arrived out of breath at the point, he saw in the middle

distance a

flotilla of canoes working its way slowly against the current. His own

friends

were busily reloading, and as he watched, another volley rang out,

which was

immediately answered by the approaching strangers. The disappointing

part,

however, was that the muskets were all pointed skyward. And in a few

minutes,

when the new canoes has reached the point, their occupants stepped

ashore and

were greeted solemnly with much hand-shaking.

The band consisted of fifty

or sixty grown people and a sprinkling of children. They were shorter

and

broader faced than Jimmy's friends, and, as he soon discovered, talked

a

different language. The men were immediately

conducted to the clearing, while

the women began unloading the canoes. In a few hours another camp had

been

established a hundred feet or so from the old one, and then began an

interchange of stately visits between the men, of giggling gossipy

meetings by

the women, of fights and final reconciliations among the dogs. With the

children it was very much the same. At first they circled warily about

one

another, then they quarrelled, then they became fast friends.

The Ojibways gave the Crees

food from the stores they had accumulated; the Crees in return

presented

various seaside luxuries, such as smoked geese and dried

salt-water fish.

Jimmy was delighted to receive from a little Cree boy a pair

of stiff

moccasins made out of seal-skin, with the fur on the inside; and to be

able to

give

in return two blunt-headed

arrows

of maple -- a wood unknown so far north.

Then followed the long lazy

days of the permanent camp. Jimmy and his companions found the

pools where

there was no current, and there they spent every day in and out of the

water.

Jimmy was tanned almost to the color of his Indian friends by the hot,

north-country sun. They fished in the riffles. They explored the woods

roundabout until they knew every inch of it for five miles, and by an

infinite

patience and many trials, they managed to kill a respectable

number of the

cock partridges, the spruce-grouse, and the brown ptarmigan. They set

their

traps for muskrats, and looked with longing eyes on the trails

of mink and a

certain beaver colony, but the elders sternly forbade them to

disturb the

fur-bearing animals at this time of year. But best fun of all was the

game of

War Party.

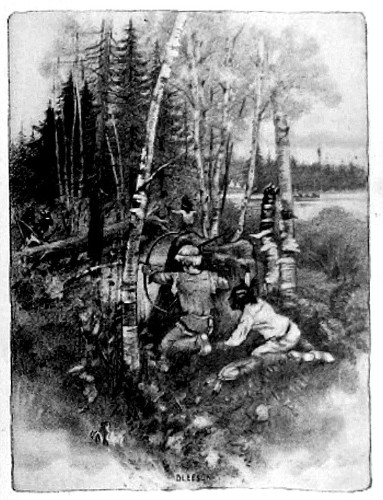

Asádi and one of

the Cree

boys would choose sides. Each boy would be armed with two or three

blunt arrows

whose points had been padded with moss, bound securely with buckskin.

One party

would disappear in the woods, and after an interval the other would

follow.

Then were ambushes, surprises, crafty retreats. The children

glided through

the forest with all the stealth of the wild animals

themselves. They lurked

behind logs,

watching with keen bright

eyes. They tracked the enemy, or covered their own trails in

order that

they might not be tracked in

turn. And at

any moment you were likely to be startled by the sharp twang!

of a bow

and bruised severely by the heavy blow of an arrow. For although the

missiles

were padded to prevent actual injury, they hurt enough to make it a

real object

not to be "killed"; for when you were killed, you had to return to

camp and play with the little girls.

Of course, Jimmy had neither

the inherited nor the acquired skill, so much of his time he

spent in camp.

But he improved rapidly, and the certainty of being black and blue in a

fresh

place added excitement to the game. And, oh, glorious thought!

twice he

"killed" members of the opposing party. Besides which he liked

the

little girls. When they were not helping their mothers they were very

kind to

him, and showed him their rag dolls and taught him divers interesting,

quiet

camp games. Some of them he liked very much.

"The children glided through the forest."

And in the camp life itself

there was always much to attract his attention. The women were making

buckskin,

were ornamenting with beads various articles of

clothing, and the men were

conducting, inside the big lodge made of poles and branches, some

mysterious and

noisy ceremony.

Jimmy never got a glimpse of

what was going on inside, but he was content to sit by the hour in the

hot sun,

listening to the

modulated rise and

fall of weird minor songs, the clatter of bones, the boom of drums, the

shuffle

of hands and feet. Every once in a while one of the men would appear

for a

moment at the doorway, his gaze exalted, his features

painted in brilliant

stripes or dots, his form dressed all in fringed buckskin lavishly

ornamented

with beads. And it was a pure delight at last, when the conjuring was

over, to

see the strangely clad men come forth into the gathering dusk and file

silently

to their teepees. Jimmy's little heart alwa ys

sensed a thrill at what

he

somehow dimly felt to be a reincarnation of a glorious past. ys

sensed a thrill at what

he

somehow dimly felt to be a reincarnation of a glorious past.

Now the days were very long.

The sun did not set until nearly nine o'clock. And at night Jimmy was

astonished and filled with awe by the brilliant aurora that shot its

many-colored flames far over the zenith.

Among the older men of the

Cree band Jimmy made no friends. This was natural, for a brave had

little time

for a child. But of course his presence was remarked by them, and

received much

discussion.

Now it happened that in the Cree

band was a French

half-breed,

Antoine Laviolette, who in winter was a post-keeper for the

Hudson Bay

Company, but who in summer preferred to travel with his savage kinsmen.

One

evening Jimmy was vastly astonished to be addressed by this man. It was

the

first English the little boy had heard since old Makwa had questioned

him.

"'Ullo!" he said;

"how you do?"

"Hullo! " replied

Jimmy.

In ten minutes they were

chatting together familiarly. And from that time on, Jimmy had

a new interest

in the long twilights after the evening meal had been eaten.

For Antoine

Laviolette was inclined by race to talk, and by nature to talk

well, and he

liked an appreciative audience.

"Jeemy!" he would

call. "Com' here! You evaire hear 'bout dose salt water, how she is

come

to be no good for drink?"

And then Jimmy, wide-eyed,

would hear of the Animal Council and its plottings against Si-kak, the

great

skunk, and how the carcajou helped to

kill him, but was

defiled with

the oil, and how the carcajou in washing himself tainted the sea-water

so that

it is unfit to drink. Or he learned why the great Manitou twisted some

of the

trees so their wood does not split straight, or why the ermine's fur changes

from red to white in winter. Or he

heard all about Hiawatha, just as you can read about him in Longfellow

to this

day, the same legends with the same names. It was all very wonderful to

him,

and it brought very close to him the animals of the woods. He came to

look on

them as the Indian does, not as inferior to himself, but merely as

different;

or, to put it the other way, he grew to consider himself and his

companions as

animals of another sort, speaking a different language, and living a

different

life, but not essentially of different race.

So he understood why when a

beaver was killed for the Moon Feast, a fillet braided of worsted and

doeskin

thongs was tied around the animal's tail, and why Ta-wap, the hunter,

dressed

in his best clothes before going out to kill a bear, and why the

cleaned skulls

of some beasts were placed on stakes near running water. For though it

was

necessary that these creatures die, the Indians did such

honors to their

spirits . .

And now in the Berry Moon a

sad event sobered the camp. For little Si-gwan

ate of a

poisonous mushroom, and in spite of the conjuring and the

herbs and the

charms, she grew sicker and weaker until she died. Then in the teepee

of her

people was the sound of wailing. The women let loose their hair and

scattered

ashes on their heads and raised their voices in lamentations, while

Au-mick,

the little girl's father, painted his face to represent mourning.

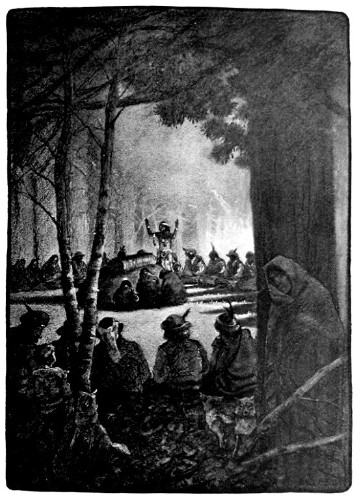

The burial services took

place in the evening between two great fires. The Indians squatted

soberly

cross-legged in a circle, all dressed in their finest garments. In the

centre

was a raised platform of boughs on which lay a birch-bark

coffin. Below it sat

the bereaved family, their hair and garments in disorder, their eyes

downcast.

Jimmy huddled near his friend, Antoine Laviolette. In the stillness,

the awe of

dark and of firelight and of dancing shadows and of a grave, silent

people

overflowed his little heart.

After a long interval old

Makwa advanced to the centre of the circle.

"Oh, Wábisi, my

little

sister," said he, addressing the mother, "it is not well that you

grieve. For if our daughter had grown, she would many times have been

hungry

and cold and weary. But now where she has gone there is no hunger nor

cold, and

there is no weariness. Therefore you should be glad." He stooped and

slashed his knife twice through the birch bark of the coffin. "Oh,

Kitche

manito!" he cried, "these places do I cut that our daughter's spirit

may come and go as she wills it, that she may visit us sometimes, that

she may

see our little sister, Wábisi, when she is very sad." Again

he turned to

the mother. "Our daughter is gone, oh, my little sister," he continued,

"but on the day when Pau-guk1

takes you, then you shall see her

again. But she will be all changed, and you will not know her, but when

you

enter that Land of the Hereafter, then you must sing always this little

song,

and so she shall know you." In a surprisingly clear and true tenor old

Makwa chanted a weird minor air with tearful falling cadences. "And

when

she hears that song," he went on, "then she will answer it with

this." He sang through another little song. The long-drawn plaintive

chords

gripped Jimmy's throat so that he sobbed aloud. " And in that way you

shall know one another."

"Old Makwa advanced to the centre of the circle."

The young men bore the

coffin to a grave that had already been dug a short distance away in

the pine

groves. After the earth had been filled in, three of the women knelt

and deftly

put together a miniature wigwam of birch bark, complete in

every detail. Then

old Makwa began again to speak, addressing the grave in a low tone of

confidence.

"Oh, Si-gwan, our

little daughter," said he, "I place this bow

and

these arrows in your lodge that you may

be armed on the Long Journey.

"Oh, Si-gwan, our

little daughter, I place this knife in your lodge that you may

be armed on the

Long journey.

"Oh, Si-gwan, our

little daughter, I place these snow-shoes in your lodge that you may be

fleet

on the Long Journey."

And in like manner he

deposited in the little wigwam extra moccasins, a model canoe and

paddle, food,

and a miniature robe.

Then quietly they all returned

to camp, -- all but Wábisi, the

bereaved mother. She huddled on the ground by

the grave,

her blanket over her head.

Jimmy dreamed that night of the silent, motionless figure of desolation.

For three whole days and

nights the Indian woman mourned her child, then arose and went about

her

ordinary duties with unmoved countenance. And the little grave was left

to the

sun and snow and rain and the mercy of an all-explaining,

all-forgetting

Nature.

And now the time had come,

at the latter end of the Berry Moon and just before the

Many-Caribou-in-the-Woods Moon, to break up the permanent camp. The

Crees had

to return to Moose Factory at the Hudson Bay, thence to set out for

their

winter trapping grounds; the Ojibways were now to retrace their steps

to Chapleau

for the purpose of receiving their treaty money from the Canadian

government.

Jimmy was not aware of the meaning of this, nor that when once

the canoes

should breast the current, he would be headed toward the railroad

again. He

only knew that a move was imminent, and was glad of it. The home camp

was fun,

but the adventures of travelling were better. He never knew how close

he came

to being taken by the Crees many, many miles farther north to his

supposed home

at York Factory on the shores of the Hudson Bay. Antoine

Laviolette was the

lucky element in that. He it was who told the headmen that the child

was not a saganash,2

as they had

supposed, but a kitch-mokamen,3

who lived far south of the

Ojibway country. So when the time came to part,

Jimmy remained with his old friends.

The

Ojibways broke camp first, as they had the

longer journey to go. When the

canoes

were all loaded, the Crees came down to wish them a good journey. And

then,

after the little craft were actually afloat, a dozen young boys dashed

into the

water for the purpose of dropping presents of fish, game, and

ornamented work

into the boats of the departing tribe. They waited thus until the

latest

possible moment in order that the recipients of the gifts

might not feel

called on to return something of equal value. A volley of musketry was

answered

by another from the canoes. The flotilla moved slowly forward against

the

current.

_______________________

1

The Death Spirit.

2 Englishman.

3 Big knife, i.e. American.

Click

the

book image to turn

to the next Chapter.

Click

the

book image to turn

to the next Chapter. |