| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

General Henry Knox

By MRS. JOHN O. WIDBER OUR country, to which we refer with pride as "The United States of America," was not in existence as such when Henry Knox was born. The thirteen original American colonies were prosperous dependencies of the mother country. Among the many emigrants who came to share the fate of the colonists here, were some of Scotch-Irish descent from the north of Ireland. The names of two of these worthy families, Knox and Campbell, were united in February, 1736, when William Knox, a Bostonian shipmaster, married Mary, daughter of Robert Campbell. This William Knox was a descendant of John Knox, a native of East Lothian, Scotland, who was known as the reformer in the times of Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth and Mary, Queen of Scots. When Carlyle undertook the self-imposed task of selecting some of the representative heroes of different countries, he chose for Scotland this same John Knox, of whom he wrote: "* * * * * himself a brave and remarkable man, but still more important as chief priest and founder, which one may consider him to be, of the faith that became Scotland's, New England's, Oliver Cromwell's. * * * * * He is the one Scotchman to whom, of all others, his country and the world owe a debt." The home of William Knox, in Boston, a two-story, gambrel-roofed house on Sea Street, was a comfortable one for those times. The seventh of their ten sons, born July 25, 1750, was christened Henry Knox. A few years later the family lost their property and when the father died in 1762 Henry, a boy of twelve, became the sole support of his mother and younger brother. Only four of the ten boys lived to grow up; the two eldest, John and Benjamin, took to a seafaring life, after which their family had no communication from them. William, the youngest boy, lived to be forty-one years of age and, during his whole life, was associated in many ways with his brother, Henry. Henry left grammar school to take a place in the book store of Messrs. Wharton & Bowes, in Cornhill, Boston. A thankful boy he was, too, for the opportunity of earning something to help his mother. Business was beginning to show the effects of political troubles which had begun to brew between England and the colonies, because of the encroachments of the mother country on what the colonists considered to be their rights. Besides attending to the many duties required of him at the bookbinder's and stationer's place at Cornhill, young Knox managed to appropriate for himself much useful knowledge from the books to which he had access. His choice of studies was governed by his great interest in military affairs and anything which he could find about generals or warriors was most carefully perused. He also learned to speak and write the French language, an accomplishment destined to prove useful in his later life, when he came to meet French officers of our ally across the water. As a young man, Knox was popular with his companions by whom he was frequently chosen to take the lead in their outdoor sports. On September 28, 1768, the citizens of Boston were enraged to see a fleet of British warships enter the harbor. Seven hundred British regulars, under General Gage, had been sent over to enforce the laws framed by the English Parliament to govern the Colonists, who, however, had no representatives in that body. The spirit of bitter revolt against the injustice of the mother country, that had long been seething in the colonies, fairly boiled at the establishment of an armed garrison within the city of Boston. On the night of March 5, 1770, as young Knox was on his way home from a visit in Charlestown, he came upon an infuriated mob near the barracks of the British soldiers in the heart of the city. A sentry had been attacked by a citizen and other soldiers, arming themselves with anything which was most convenient, rushed to his aid. This action led to the gathering of a mob of excited people. Another sentry was attacked in front of the custom house on King Street and six men were sent to aid him. At this the people began to jeer at the soldiers till, finally, Capt. Preston arrived with six more men to aid the soldiers who were on duty in front of the custom house. Knox used all the eloquence of which he was capable in urging Capt. Preston not to fire upon the people, but to withdraw his men into the barracks, but someone in the crowd struck at a soldier with a club and he, without waiting for orders, fired back. Other random shots followed, the result of which was the killing of three Boston citizens and the wounding of several others. This affair, known in history as the "Boston Massacre," maddened the people still more and resulted in the withdrawal of the British troops to Castle William on a little island in the harbor. Soon after this, Henry Knox went into business for himself by opening "The London Book-Store" in Cornhill. His place was well stocked with the latest books and a complete assortment of stationery. Later he added to his business by doing bookbinding. His store became a popular resort for young and old, while British officers and Tory ladies were frequent customers. A certain young lady of the fashionable Tory society, Miss Lucy Plucker, became one of the most frequent callers at Knox's store. She seemed to be very fond of reading, especially of books sold by Knox and soon an intimacy sprang up between the young bookseller and his distinguished patron. Their regard for each other was mutual, but her parents, who were aristocratic Tories, were bitterly opposed to a union of their daughter with one of so plebeian an origin as was Henry Knox.  Major-General Henry Knox A few years before this, Knox joined an artillery company known as "The Train," commanded by Maj. Adino Paddock. The company was well drilled by him and further instructed by British officers of a company of artillery who, on their way to Quebec, remained at Castle William during the winter of 1766. Thus the British officers were, all unknowingly, training soldiers whom they were afterwards to meet on the battlefield. The "Boston Grenadier Corps" was formed from apart of Paddock's company, of which Henry Knox, at the age of twenty-two, was second in command. The members of this artillery company distinguished themselves for their fine appearance and precise movements when on parade. Every one of the British officers gave them the tribute of saying that "A country that produced such boy soldiers, cannot long be held in subjection." It is not to be wondered at that Miss Flucker was more than ever in love with gallant young Knox when she saw him on parade in the becoming uniform of the new company and knew that he could not be unconscious of the admiring glances of other young ladies besides herself. He was accustomed to wear a silk scarf wrapped around his left hand to conceal a wound which he had received while out gunning on Noddle's Island in the summer of 1773, when the bursting of his fowling-piece deprived him of the two smaller fingers. In painting his portrait many years later, Gilbert Stuart skillfully concealed this loss by having the General place his left hand on a piece of artillery. Thomas Flucker, the father of Miss Lucy, royal secretary of the province, tried to make her believe as he did, that, when the colonies were subdued by the Imperial Government, she would, if united with Knox, regret having acted contrary to the advice of her parents. But all this only seemed to fan the flame of her ardor and the love-making was continued. At last, thinking it better than to have an elopement in the family, her parents gave a reluctant consent to the marriage, which was performed by Rev. Dr. Caner on June 20, 1774. The happy pair at once began housekeeping, but not for long was the blessing of a peaceful home to be theirs, for, as the breach between the colonies and the mother country widened, the lover husband felt it his duty to go where his country might have most need of his services. As Knox was known to sympathize with the colonists his movements were watched and he was forbidden to go away from the city. *

* *

Meanwhile, Henry Knox, who was still doing quite a thriving business in his bookstore, had been asked several times to go into service in the royal forces for lucrative purposes, but he declined all such offers. At last, on the 19th of April, he determined that he could no longer stay away from the colonial headquarters at Cambridge, where the minute-men from towns both near and far were now gathering. Leaving his brother, William, in charge of the bookstore he left Boston that night, accompanied by his wife, who had his sword concealed in the quilted lining of her mantle. Knox went into headquarters of General Artemas Ward at Cambridge, who at that time had command of our soldiers, called the "rebel" troops, around Boston, and offered his services as a volunteer. The siege of Boston was now begun and within a few days an untrained army of about sixteen thousand men had gathered there in readiness for the inevitable conflict. In the work of fortifying the city, Knox's previous study of military matters was put to good use. As his abilities came to be appreciated, he was sent to the vicinity of Charlestown to make plans for other formidable works. The later orders of Gen. Ward were in accordance with the plans made by Knox. After the battle of Bunker Hill, Mrs. Knox was taken to Worcester as a matter of safety, while her husband was vigorously engaged in helping some of the principal officers of the army in planning needed fortifications and superintending their construction. Soon after General Washington had taken command of the Army at Cambridge, he made an inspection of the works around Boston and was well pleased with them. As for Knox, he was filled with admiration for the great general and the manner in which he conducted his duties. He was frequently in conference with him in regard to military affairs and a friendship sprang up between them which lasted through life. It required a long time to prepare for the siege of Boston. The most imperative need was for more siege guns and there seemed to be no way of procuring them. At last an idea came to the resourceful Knox, which, impractical though it seemed at first, was eventually carried out. Our forces had taken possession of a large supply of ordnance at the capture of Fort Ticonderoga by Ethan Allen on May 10, 1775, and Knox's hazardous plan was to transport that artillery by the crude methods of those times hundreds of miles across lakes, rivers and mountain ranges, all the way from Ticonderoga to the heights of Dorchester. This was indeed a bold plan, for Knox at that time was only twenty-five years old and his brother, William, who accompanied him on that memorable trip, was about nineteen. The bookstore at Cornhill had been looted by the British and Tories before this time. After careful consideration, Gen. Washington gave his consent to the plan, and in his final instructions to Knox said that the want of cannon was so great that "No trouble or expense must be spared to obtain them." Knox thought that the total cost of the expedition need not exceed one thousand dollars, but in one of his account books is found the following short but comprehensive entry: "For expenditures in a journey from the camp around Boston to New York, Albany, and Ticonderoga, and from thence, with 55 pieces of iron and brass ordnance, 1 barrel of flints and 23 boxes of lead, back to camp (including expense of self, brother, and servant), £520.15.8 3/4." Gen. Washington instructed Gen. Philip Schuyler of Albany to aid Knox in any way that he could and he did much to help in procuring means of transportation, which were flat bottomed scows, in which to ferry guns across Lake George, and heavy ox sleds on which to drag them across frozen rivers and over roads not made for such heavy traffic. On a stormy December evening, when Knox was on his way between Albany and Ticonderoga, he stopped at a rude log cabin where travelers in that lonely region sometimes passed the night. Another man of about his own age slept on the floor with him under the same blankets. Each found the other an agreeable companion and their conversation on subjects of mutual interest was such as had probably never been discussed under that roof before. Knox's companion displayed an intelligence and refinement that impressed him favorably and not until morning did they make known their identity to each other. Fate sometimes plays strange tricks for Knox's bedfellow was none other than Lieut. John Andre, a prisoner taken from the British by Gen. Richard Montgomery at St. John's when on an expedition to Canada, and now on his way to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to await an exchange. A few years later when Andre, adjutant general of the British Army, was sentenced to the ignominious but deserved death of a spy, it fell to the lot of Henry Knox to be one of the general officers of the court-martial before which he was tried and sentenced. Knox performed this duty, though it was painful, because of the pleasant memories of that winter night in the bleak New York wilderness nearly five years before, when he and Andre had enjoyed pleasing converse together. *

* *

Many of the letters written and received by Knox have been preserved and are now in the possession of The New England Historic Genealogical Society of Boston. The reading of these time-yellowed missives gives one a clearer idea of his character than can be obtained by the description of another. Those which he wrote to his wife show that he always held toward her the most affectionate devotion. A letter written from Albany on January 5th, 1776, gives a brief account of his adventures amidst ice, snow, forest and blind roads up to that point, and then goes on to tell something about the cities through which he passed. Speaking of New York he wrote: "The people, — why, the people are magnificent: their equipages, which are numerous; in their house furniture which is fine; in their pride and conceit, which is inimitable; in their profaneness, which is intolerable; in the want of principle, which is prevalent; in their Toryism, which is insufferable, and for which they must repent in dust and ashes." After writing more about Albany, the letter closes as follows: "It is now past twelve o'clock, therefore I wish you a good night's repose and I will mention you in my prayers." Knox reached Ticonderoga December 5th, and as promptly as possible got the unwieldy mass of ordnance started on its long journey. There were 55 pieces of ordnance as follows: 8 brass mortars, 6 iron mortars, 2 iron howitzers, 13 brass cannon, 18 and 24-pounders, and 26 iron cannon, 12 and 18-pounders, 2300 pounds of lead and a barrel of flints. The homeward trip was fraught with much hardship and delay. A letter which Knox wrote to Gen. Washington from Fort George, December 17th, gives a word picture worth reading. Following are a few lines of that letter: "It is not easy to conceive the difficulties we have had in transporting them across the lake, owing to the advanced season of the year and contrary winds; but the danger is now past. Three days ago it was uncertain whether we should have gotten them until next spring, but now, please God, they must go. I have had made 42 exceedingly strong sleds, and have provided 80 yoke of oxen to drag them as far as Springfield where I shall get fresh cattle to carry them to camp. The route will be from here to Kinderhook (New York) from thence to Great Barrington (Mass.), and down to Springfield. I have sent for the sleds and teams to come here, and expect to move them to Saratoga on Wednesday or Thursday next, trusting that between this and then we shall have a fine fall of snow, which will enable us to proceed further and make the carriage easy. If that shall be the case, I hope in sixteen or seventeen days' time to be able to present to your Excellency a noble train of artillery." At this point they were delayed because the needed snow did not fall for some days. On the way from Ticonderoga to Albany he found it necessary to cross the Hudson river four times. A January thaw made the ice unsafe for such ponderous loads and he was obliged to wait for severely cold weather to harden it. A letter written to his wife during this wearisome delay, begins like this: "My Lovely and Dearest Friend: Those people who love as you and I do never ought to part. It is with the greatest anxiety that I am force'd to date my letter at this distance from my love, and at a time, too, when I thought to be happily in her arms." Knox's determined perseverance finally overcame all obstacles and sometime before the first of March he had planted the coveted artillery on the fortifications at Dorchester Heights. On the morning of March 4th, the British were astonished to find the harbor and all the southern part of Boston under the "rebel" guns — Howe was forced to evacuate the city and with nearly nine thousand troops, he sailed away to Halifax. Eleven hundred loyalists, or Tories, among them Mrs. Knox's father and his family, left at the same time. But, as secretary of the province, from which he had been forced to flee, he continued to draw £300 a year salary till some years later. In one of Mrs. Knox's letters to her husband in July, 1777, she comments on the drollness of this fact. Howe's army, which left on March 17, 1776, had suffered some privations during their long stay in Boston. Fuel was very scarce. They had even used for firewood the old North Church, from the belfry of which the lanterns had been hung as a signal to Paul Revere. Gen. Knox rode with the army into Boston thought that his brother tried to piece together the remnants of the wreck of the book store, as Knox's letters to him from this time indicate that William remained in Boston. As it was thought that after Lord Howe's fleet had been recruited at Halifax, he would try to seize New York and the Hudson River, the American army was hurried to New York to make fortifications and prepare for the expected invasion. Knox was sent to Connecticut and Rhode Island to plan needed fortifications for places on the coast. His wife and a little daughter, Lucy, lately arrived, accompanied him a part of the way, staying for safety first at Norwich and later at Fairfield, Conn. The long-looked-for arrival of the enemy was on June 25th, Howe's forces outnumbering ours by at least six thousand men. He established himself on Staten Island and for a time there was comparative quiet. Mrs. Knox and little Lucy came for a visit to Knox's headquarters which were in the vicinity of what is now Broadway. She had been there but a short time, however, when a panic occurred in New York because some British ships were seen coming through the Narrows, and Mrs. Knox was precipitately returned to Connecticut. Before the beginning of hostilities, Admiral Howe sent a flag of truce up to the city. Colonels Reed and Knox went down in a barge to receive the message, but when the officer said he had a letter from Lord Howe to Mr. Washington, Col. Reed refused to receive the communication because it was not properly addressed. A few days later, the adjutant general of Gen. Howe's army was sent to interview General Washington. Knox wrote a long letter to his wife about the interview which took place at his house. He spoke of the futility of the efforts of this man, Col. Patterson, to get any concessions from General Washington who he states "was very handsomely dressed and made a most elegant appearance." For several months one misfortune followed another until it seemed to all but the most altruistic that the patriot cause was doomed. The British having taken full possession of the island of Manhattan, the remainder of Washington's army began to retreat across the Jerseys. It was late in November and bitterly cold. Gen. Howe believed that the American army would now decrease as the term of enlistment for many of the men expired in December, so he left Col. Donop with his Hessians and a Highland regiment to hold the line across the Jerseys and returned to winter quarters at New York. Washington wrote to the Governor of New Jersey and told him to be prepared for an invasion, also that it was best for the people to destroy their grain, stock or other effects which might be of use to the enemy. While Washington was crossing the Delaware on his way to Pennsylvania, the British troops were marching into Trenton. In order to prevent pursuit Washington had taken possession of all water craft up and down the river for seventy miles. In order to surprise the enemy, Washington decided to try to recross the Delaware Christmas night, and make an attack on Trenton. Letters from Knox to his wife give graphic descriptions of the movements of the army that memorable night. They found the enemy entirely unprepared and after a sharp, decisive battle the American victory was complete. He closed his letter with saying, "His Excellency, the General, has done me the unmerited great honor of thanking me in public orders in terms strong and polite. This I should blush to mention to any other than you, my dear Lucy; and I am fearful that my Lucy may think her Harry possesses a species of little vanity in doing it at all." On Dec. 27th, the day following the famous battle of Trenton, but before the news of it had reached Congress, it had ordered a commission for Col. Knox by which he was made a brigadier-general. In writing to his wife from Trenton on Jan. 2, 1777, Knox tells her of his advancement and goes on to say: "People are more lavish in their praises of my poor endeavours than they deserve. All the merit I claim, is my industry. I wish to render my devoted country every service in my power; and the only alloy I have in my little exertions is that it separates me from thee, — the dearest object of all my earthly happiness. May Heaven give us a speedy and happy meeting. — The attack of Trenton was a most horrid scene to the poor inhabitants. War, my Lucy, is not a humane trade, and the man who follows it as such, will meet with his proper demerits in another world." After this came the battle of Princeton, another American victory, as when it was over the enemy instead of being within nineteen miles of Philadelphia, were now sixty miles away with the numbers diminished by about five hundred. Washington and his army went into winter quarters, an assemblage of huts at Morristown. Congress had finally decided to establish a foundry for casting cannon and laboratories for the manufacture of powder. Knox was sent to New England to oversee these matters. While there he visited his wife who was then in Boston. It was on his advice, in a letter to Washington from Boston, Feb. 1, 1777, that the works which finally became the United States arsenal at Springfield, were established. A little later occurred the birth of Knox's second child and Mrs. Knox was staying with Mrs. Heath, wife of the Major-General Heath at Sewall's Point, now Brookline, Mass. The news of Burgoyne's surrender to Gates at Saratoga, on October 18, 1777, was received by the patriots with great enthusiasm. Before this, Knox in writing to his wife, soon after the battle of Stillwater or Freeman's Farm, Sept. 19, says: "Observe, my dear girl, how Providence supports us. The advantages gained by our Northern army give almost a decisive turn to the contest. For my own part, I have not yet seen so bright a dawn as the prospect, and I am as perfectly convinced in my own mind of the kindness of Providence toward us as I am of my own existence." Knox had obtained leave to visit his wife in Boston. Gen. Greene, writing to him from Valley Forge, February 26, 1778, tells of the terrible sufferings of the army and the imperative need of clothing and food. General Knox and a Captain Sargent were detailed to inform Congress of the sufferings of the starving and almost naked patriot soldiers at Valley Forge. General Knox's weight, which was the greatest of the eleven most important officers, was 280 pounds, while that of Washington was 209 pounds. To show off in a witty and sarcastic manner, one of the Congressmen, who had listened to General Knox's impartial statement of the needs of the soldiers who had been giving their all to their country's service, said he had not for a long time seen a man in better flesh than General Knox or one better dressed than Capt. Sargent. Knox maintained a discreet silence but his associate retorted "The corps, out of respect to Congress and themselves, have sent as their representatives the only man who had an ounce of superfluous flesh on his body and the only other who possessed a complete suit of clothes." The wives of several of the officers were at Valley Forge that spring, among them Mrs. Washington and Mrs. Knox. The latter remained with our army or very near its headquarters till the close of the war and vied with General Knox himself in popularity. While our army was in winter quarters at Pluekemin, N. J., in the winter of 1779, General Knox tried to make a beginning of an academy for training officers for the army. This was built in the form of a parallelogram. He had built an auditorium, 50x30, where the men listened to lectures on tactics and gunnery. Work huts were built for those employed at the laboratory. Field pieces, mortars and heavy cannon were arranged to form the front side, huts of officers and privates formed the other sides. Although this camp was hastily built in only a few weeks it was well arranged and of good appearance. This humble beginning led to the establishment years later of the Military Academy at West Point, N. Y., which is today one of the finest in the world. That spring a great celebration was held, near the headquarters, at Pluekemin, in honor of the anniversary of the conclusion of the treaty with France the year previous. A part of Thatcher's account of it reads as follows: "A splendid entertainment was given by General Knox and the officers of the artillery... The celebration was concluded by a splendid ball opened by his Excellency General Washington, having for his partner the lady of General Knox." The cares of motherhood must have sat lightly upon Mrs. Knox, for she seems to have been the life of nearly every social gathering spoken of during that trying time in our country's history and she was well-fitted for all such duties. In the summer of 1779 occurred the death of their second little daughter, and Gen. Washington took time from his own anxious cares to write a note of condolence to the bereaved mother. In May, 1781, Gen. Washington and Knox went to Connecticut to meet Count de Rochambeau in order to plan for the siege of New York, when they heard that Count de Grasse, with a French fleet of twenty-eight of the line and six frigates bearing twenty thousand men was about to sail for Chesapeake Bay from the West Indies. They then changed their first plan, although keeping up the appearances of carrying it out, while they were secretly preparing to go to Virginia and undertake the capture of the British Army. Washington considered it so necessary to deceive Clinton that he kept the plan secret except from a few of the most trusted officers. It would seem that Mrs. Knox, who was then up near Albany on a visit, wrote to her husband to learn something about the military situation and the following letter, written from the camp near Dobb's Ferry, August 3, 1781, shows the tactful manner in which he parried her queries: "Yesterday was your birthday. I cannot attempt to show you how much I was affected by it. I remembered it and humbly petitioned Heaven to grant us the happiness of continuing our union until we should have the felicity of seeing our children flourishing around us and ourselves crowned with virtue, peace, and years, and that we both might take our flight together, secure of a happy immortality * * * * * All is harmony and good fellowship between the two armies. I have no doubt, when opportunity offers, that the zeal of the French and the patriotism of the Americans will go hand in hand to glory. I cannot explain to you the exact plan of the campaign: we don't know it ourselves. You know what we wish, but we hope for more at present than we believe." Washington's temporary headquarters were at Williamsburg, Virginia, and from there the Commander-in-chief Knox, Rochambeau, Duportail and Chastellux went down to De Grasse's fleet and in Chesapeake Bay, and on board the "Ville de Paris," arranged a co-operation plan. Afterwards De Grasse announced his intention of putting to sea so as to meet the enemy outside. As it was feared that this might upset their plan of cutting off all hope from seaward for Cornwallis, Lafayette and Knox were sent to De Grasse and they persuaded him to remain where he was. Gen. Greene, a steadfast friend of Knox, wrote from his camp on the Santee, South Carolina, at about this time. By the purport of his letter, he evidently thought lack of means the reason why the operations against New York had not yet begun. He speaks of his young god-son, as follows: "I long to see you and spend an evening's conversation together. Where is Mrs. Knox? and how is Lucy, and my young god-son, Sir Harry? I beg you will present my kind compliments and best wishes to Mrs. Knox. — Please to give my compliments to your brother and tell him we are catching at smoky glory while he is wisely treasuring up solid coin." This young "god-son, Sir Harry," was the baby at whose christening the Marquis de Lafayette officiated, as god-father. Many years later, after both General and Mrs. Knox had died, Lafayette visited this country in 1825 and, at that time, in an interview with Mrs. Thatcher, he told her of the peculiar circumstances of the christening of her brother, Henry Jackson Knox. One god-father, the Marquis, was a Roman Catholic; the other god-father, General Greene, a Quaker; Mrs. Knox, an Episcopalian; and the General, a Presbyterian. For several weeks the enemy was beguiled by the strategy of Washington until in August, having learned that Count de Grasse would soon arrive, he got the armies ready for a combined attack. Meanwhile, Gen. Knox had been procuring as large a force of artillery as possible and, as Washington said in his later report to Congress in speaking of the services of Knox: "the resources of his genius supplied the deficit of means." The bombardment of the city began on October 6th, and the British works, unable to withstand such a cannonade as came from the allied troops, crumbled and fell. On the 17th of October, 1781, just four years after the surrender of Burgoyne, Cornwallis surrendered and his entire army of more than eight thousand men became prisoners of war. The next morning, Knox wrote to his wife, who had been staying since September with Mrs. Washington at Mount Vernon: "I have detained William until this moment that I might be the first to communicate good news to the charmer of my soul. A glorious moment for America! This day Lord Cornwallis and his army march out and pile their arms in the face of our victorious army. * * * * * The General has just requested me to be at headquarters instantly, therefore, I cannot be more particular." On the recommendation of General Washington, Knox was promoted by Congress as Major-General dating from November 15, 1781. From now on his headquarters were at West Point and he was appointed to the command of that post August 29, 1782. He at once began to strengthen the fortifications. Washington showed implicit confidence in him, when writing instructions, by saying: I have so thorough a confidence in you, and so well acquainted with your abilities and activity, that I think it needless to point out to you the great outlines of your duty." On April 19, 1783, exactly eight years after the battle of Lexington, General Washington declared war ended and disbanded the army. The Chevalier de Chastellux, a Major-General in Rochambeau's army and a member of the French Academy, became greatly attached to General and Mrs. Knox during his stay in America. After his return to France he corresponded with Gen. Knox. One of his letters, dated March 30, 1782, speaks of the then recent alliance of our country with France. He says: "My sentiments will always meet yours, and I hope that I shall not be excelled in serving America and loving General Knox. Let us be brothers in arms, and friends in time of peace. Let the alliance between our respective countries dwell in our bosoms, where it shall find a perfect emblem of the two powers: in mine, the seniority; in yours, the extent of territory. "I depend upon your faith, and I pledge my honour that no interest in the world can prevail over the warm and firm attachment with which I have the honor to be DE

CHASTELLUX."

Just before this, the active mind of Knox had planned the forming of a society to perpetuate the friendships formed by officers of the army and provide for their indigent widows and surviving children; each officer on joining the society was to contribute to its funds his pay for one month. The society to be known as "The Cincinnati" in honor of the illustrious Quinctius Cincinnatus, as these officers were resolved to follow his example and return to citizenship. Some there were who laughed this idea to scorn, nevertheless the officers of the army did form such a society, whose existence even to this day testifies to the wisdom of its founders, and their illustrious example still helps to keep alive the fires of patriotism throughout our land. On August 26, the delicate task of disbanding the army at West Point was intrusted to General Knox. After concluding his labors at West Point, General Knox returned to live one year in Boston. Congress decided in 1785 to continue the office of Secretary of War and on March 8, 1785, elected Knox to fill that office. Washington, who felt assured of the wisdom of this appointment, wrote to Knox, saying: "Without a compliment, I think a better choice could not have been made." The way in which Secretary Knox conducted the duties of his office during the critical period between the close of the war and the adoption of the Constitution evidently fulfilled the anticipations of his chieftain, for, in 1789, Knox was re-appointed Secretary of War by President Washington. The army then numbered about seven hundred men and the beginnings of a navy were entrusted to his care. He also had charge of the Indian affairs. Knox's establishment at New York was costly and he maintained a high social standing. Rufus W. Griswold, in speaking of Gen. and Mrs. Knox, at this time, says: "She and her husband were, perhaps, the largest couple in the city and both were favourites, he for really brilliant conversation and unfailing humor, and she as a lively and meddlesome but amiable leader of society, without whose co-operation it was believed by many besides herself that nothing could be properly done in the drawing room or the ball-room, or any place, indeed, where fashionable men and women sought enjoyment." After having served his country well for nearly twenty years, Secretary Knox decided to withdraw from public duties his devote himself to the needs of his family, accordingly he sent in is resignation and retired from President Washington's cabinet at the close of the year, 1794. Before this, Knox had become the possessor, partly through his wife's inheritance and partly through purchase, of a vast tract of wild land in Maine, being the greater part of what was known as the Waldo patent, which was originally the property of Mrs. Knox's grandfather, Gen. Samuel Waldo of Massachusetts. This land, which was bounded on either side by the Penobscot and Kennebec Rivers, included nearly all of what is now Knox, Waldo, Penobscot and Lincoln Counties. Holman's Day's poem, "When General Knox Kept Open House" speaks of the General's domains in Maine. The first and last stanzas are as follows: "From

Penobscot to the Kennebec, from Moosehead to the sea,

Was spread the forest barony of Knox, bluff Knox; And the great house on the Georges it open was and free, And around it, all uncounted, roved its bonny herds and flocks.

*

* *

"Oh,

welcome was the silken garb, but welcome was the blouse,

When Knox was lord of half of Maine and kept an open house."

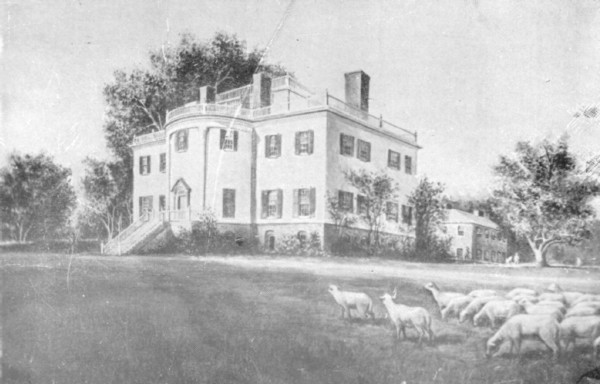

Gen. Knox and two of his friends, Henry Jackson and Royal Flint, formed an organization known as the Eastern Land Associates, and in 1792 they purchased from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts an immense tract of wild land in Maine. This was estimated to contain 2,000,000 acres, bounded on the south by land they had purchased previously; on the west by a line six miles from the east branch of the Penobscot River; on the east by the Schoodic River; and on the north by the line between Canada and Maine. They paid $5,000 within a month and the balance in $30,000 annual payments. This was afterwards sold to Hon. William Bingham of Philadelphia and known as the Bingham purchase. It is thought that Gen. Knox probably used money obtained from this sale to start the building of his fine mansion at Thomaston in 1793. The site which he selected for his future home was well chosen on the banks of the river Georges, near that of the old fortress, protected by the forest from the cold northeast winds, and exposed in summer to the cooling southwest breezes, which rarely failed to come with the tide, and refresh the balconies on hot afternoons. From the front, the view down the river, eight or ten miles to the sea, was delightful. The house had a basement of brick and two stories above, built of wood from the estate and a fourth story was cupola-like in the centre, part of the roof being of glass. Carved wood urns ornamented the corners of the roof. The outbuildings, stables, farm-house, cookhouse, etc., were built a little distance back so that, with the mansion in the center and nine buildings on either side, a large crescent was formed, slanting back from the river. From a part of these buildings, a covered walk led to the mansion. The whole was in imitation of the style of the best Virginia homesteads of that day. The road in front of the house ran to the stable on the east. What is now Knox Street in Thomaston, was formerly the driveway and the gateway was surmounted by the figure of an American Eagle of carved wood. After the opening of Knox Street this gate was removed and one entered the estate of General Knox by a double gate at the foot of Knox Street. The center of this gate was also ornamented by a carved wooden eagle. The mansion was named "Montpelier" by Mrs. Knox. It has been stated that this came about through a French taste which she had acquired from an intimacy with Mrs. Bingham, wife of Senator Bingham, of Philadelphia, who was for some time a resident of France. The mansion was 52 feet wide and 42 feet deep. The two corner room were 16 feet square; the oval, or bow-room, in the center was 20 feet long and 16 feet wide. This was the General's reception room. A portrait of General Knox by Gilbert Stuart, and one of Thomas Flucker by John Singleton Copley hung on the walls. Settees brought from France were, a part of the furniture. Mrs. Knox's piano was the first brought to that region. The French settees and the sideboard which came from the Tuileries palace, are now owned in Portland. The floors were uncarpeted in the General's day. The walls of the wide halls and staircases were covered with a background of buff-colored paper, resembling tapestry, and large embossed brown paper figures of men, dressed in old costumes with guns, ornamented the sides of the staircases. Back of the parlor was the dead-room. The black-bordered, lead-colored walls and sombre floor seemed to the designer eminently fitting for the sad uses to which the room was put whenever death had entered the home. In the library, were pictures of ladies, reading. Here were Gen. Knox's sixteen hundred books, the second largest collection in Maine. About one-fourth of these were in the French language.  Montpelier The Home of General Knox at Thomaston To this lovely home, situated amid the beautiful trees, which had been growing for years on these ancestral acres, came, in the early summer of 1795, General and Mrs. Knox from Philadelphia. Thus was brought into the quiet village of Thomaston a new mode of life and a new series of activities such as the plain people of this old-fashioned village had never before witnessed Many are the stories still told of General Knox and the state which he maintained at Montpelier. When General Knox came to Thomaston, he was forty-five years of age and in the full vigor of manhood. His well-kept, commanding, military figure added an air of grandeur to the streets of Thomaston. The sound of his voice was in keeping with is person, and, in listening to him, one realized that he had been one to give orders, instead of to take them. The "stentorian" voice of General Knox which was audible "above storm of battle elements combined" is frequently spoken of by his biographers. He was, however, exceedingly kind and considerate of others. He was of a cheerful, optimistic nature and was never so happy as when contributing to the enjoyment of others. Yet he never relinquished his dignity and all who came to know him realized that he was a man of superior intelligence. The peculiar way in which he signed his name (HKnox), the last stroke of the H forming the first part of the K, was a habit acquired in his youth. General Knox's family, when he came to Thomaston, consisted of his wife, eldest daughter, Lucy F., who afterwards became the wife of Ebenezer Thatcher, then a young lady of nineteen; Master Henry, also called Harry, the "spoiled child" of fifteen; and the youngest child, Caroline, who afterwards became Mrs. James Swan, and later the wife of Senator Holmes, then a charming little miss of four years. The home of Gen. and Mrs. Knox was honored by many distinguished visitors. Among these were: Talleyrand, Louis Phillippe, the Duke de Liancourt, Rochefoucauld, the Viscount de Troailles, Alexander Baring, who later bore the title of Lord Ashburton, and many other famous men. Nathaniel Hawthorne visited Montpelier some years after the death of General and Mrs. Knox. At one time General Knox invited the entire tribe of Tarratine, or Penobscot, Indians to come for a visit. They all came and, to all appearances, greatly appreciated the repasts which General Knox caused to be provided for them. Finally, after these enormous feasts had depleted the larder of General Knox and exhausted his patience by weeks of continuance, he felt constrained to say to the chief: "Now we have had a good visit, and you had better go home." As "Uncle Side-linger" has aptly expressed it "That was sartinly givin' Thanksgivin' comp'ny a good, hard hunch, but some Injuns need it." It was not for lack of energy that the many schemes of General Knox for making a fortune out of the natural resources of his vast estate did not succeed; for he began at once to set up saw-mills, lime-kilns, marble-quarries and brick yards; also constructed vessels, locks and dams. He bought Brigadier's Island from "squatters" on his own property and turned it into a stock farm for the breeding of imported cattle. The cost of carrying on so many branches of business, in none of which he had had any previous experience to guide him, proved too heavy a drain on his resources. Disputes about the boundaries of the islands in the Waldo patent caused General Knox to enter into ex. pensive lawsuits and, with all this on his hands, it is not surprising that he became heavily involved in debt. Some of the best friends he had made while in the army became his heaviest creditors. He borrowed money on mortgages, which he was never able to pay. His financial straits were not relieved before his life of vigorous activity was abruptly ended on October 25, 1806, by his having inadvertently swallowed a small fragment of chicken bone, which, lodging in the æsophagus or stomach, caused him great suffering which finally ended in mortification and death. His funeral was held on October 28, with military honors, and his body placed in a tomb near his favorite oak tree, under whose cooling shade he had often rested. This tomb, proving susceptible to injuries from frost and water, the remains were removed seven years later to another on the bank of the river and, three years later, for similar reasons again removed to a place a short distance east of the mansion, near a grove of his beloved trees. *

* *

Life at Montpelier now underwent a radical change, for the estate, when administered upon by the General's widow, proved insolvent. Her remaining years were spent in the seclusion of her home, as she preferred this to going out in any other style than that to which she had been accustomed. Much of the beauty of the mansion now gradually passed away. Gates, fences and outbuildings became dilapidated and were removed. The piazza, colonnade and balconies surrounding the mansion, became much in need of repair and were finally removed a year before the death of Mrs. Knox, which occurred June 20, 1824. The marriage of General Knox's youngest daughter to Senator Holmes occurred in 1837 and his coming to the family home wrought many changes for the better. Everything was kept up as nearly like its former grandeur as possible, considering the ravages of years. After his death, Mrs. Holmes continued her residence there, but although she did the best she could with her slender means, she was unable to make repairs and improvements as needed, and the estate deteriorated as time went on. Her death occurred in 1851, and then came to Montpelier the last members of the Knox family who ever occupied the ancestral home, Mrs. Lucy Thatcher, then a widow, and her daughter, Mrs. Hyde, who died a year previous to her mother in 1854. The estate then descended to a grandson of General Knox, Lieut. Henry Knox Thatcher of the U. S. Navy, who, maintaining that the expense of keeping up the mansion and the necessary entertainment was greater than he could bear, demanded its sale at any figure. Mr. Woodhull, the executor, endeavored to sell to some one who would preserve it, but that was not to be achieved. That was a commercial era, almost utterly devoid of sentiment or the sacrilege of destroying that historic mansion never would have been permitted. The Legislature of 1871 was asked to purchase it for $7,000, but the senator from Knox County cautioned the representatives of that county against voting favorably until they had consulted their towns, as it might cause a heavy tax upon these towns, so no definite steps were taken. Before the Legislature met again, the Knox & Lincoln Railroad was constructed and passed between the mansion and the servants' quarters. The house was then sold for $4,000 by local parties and torn down. At this time the remains of Gen. Knox and other members of the family which were in the tomb, were removed to the cemetery, which had been one of his gifts to the town. A plain marble shaft bearing the following inscription was placed over the grave: MAJOR-GENERAL

H. KNOX who died Oct'r 25th, 1806. Aged 56 years. " 'Tis Fate's decree; Farewell! thy just renown, The Hero's honour, and the good Man's crown." For a long time the lot had an uncared-for appearance, but a few years ago a great-granddaughter of General Knox, Mrs. Fowler, caused it to be enclosed by a handsome curbing of granite and also had the monument raised and placed upon a granite base. The part of the monument bearing the inscriptions, is square, surmounted by a pyramidal top about nine feet in height. The inscription in honor of the General is on the southern side; the names of Mrs. Lucy Knox, his widow, who died in 1824, and their daughter, Caroline Holmes, the wife of Hon. John Holmes, who died in 1851, are inscribed on the western side; those of Henry Knox, the son, Mr. Swan (the first husband of Mrs. Holmes), and Mrs. Lucy K. F. Thatcher, the eldest and last surviving child of General Knox, on the eastern side; the names of the nine children, who died in infancy, or early childhood, are on the northern side. At either side of the monument are light marble stones, on the western of which are carved the names of Ebenezer Thatcher and daughter, Mrs. Hyde; and on the eastern, the name of James Swan Thatcher, who was lost at sea in the U. S. Schooner, Grampus, in March, 1843. The grave of Senator Holmes is also here, but the monument erected to his memory, is in Alfred, Maine, where he lived the greater part of his life. During the life of General Knox, his son, Harry Jackson Knox, was nominated a midshipman in the U. S. Navy, but this failed to be confirmed by the Senate. Later, he did enter the navy but won no special credit. He changed greatly during his last years, became deeply religious, and evidently, through remorse because he had not always borne with honor the illustrious family name, requested that he be buried in a very deep grave in the burial ground at Thomaston, and that his last resting place should always remain unmarked. Thus it is; the spot denoted only by an iron fence. What is now the railroad station in Thomaston is one of the original buildings erected by General Knox in 1793, and used by him as the farm house. The original walls of this house remain to-day, and it has never been moved. Another of the outbuildings is on the same spot where it was built and now forms part of a mill. "Montpelier's stately roof is low and scattered all its gear; Its plenteous cellars have been choked with earth for many a year." The bell which General Knox hired Paul Revere of Boston to cast, purposely to be hung in the tower of the North Parish Church on Mill River Hill, during the years of his residence in Thomaston, and for which the receipted bill found in Knox's papers shows that the cost was Four Hundred Dollars, is still in use; about fifteen years after General Knox had died, the bell became cracked and was sent to the Paul Revere works to be recast. The original motto written by General Knox was not preserved and the lettering at present is:  Plans for attempting what seems to be the only thing which can now be done in the way of reparation, to build a fire-proof reproduction of "Montpelier" in which to collect and preserve such relics of the Knox family as can be obtained either by gift or by loan, are now being made by the General Knox Chapter of The Daughters of the American Revolution, at Thomaston. If the public responds to their calls for sympathy and co-operation, and Congress should make an appropriation for that purpose, Maine may, in time, have a memorial to General Knox second only in historic interest to Mount Vernon. Unquestionably, General Knox was one of the most distinguished citizens who ever made his home in Maine. His valor, ingenuity and military skill caused him to become, first, Washington's trusted friend, then his chief of artillery, of which office he faithfully and efficiently discharged the duties under the successive ranks of colonel, brigadier-general and major-general to the end of that historic struggle, known as the Revolution; and, furthermore, as President Washington's Secretary of War he helped establish the first successful federal government in history. |