| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2008 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

ON THE CONNECTICUT SOUTH HADLEY, the seat of the

college for girls, and Hadley, the supposed original home of the Hadley chest,

are quaint towns which arrest us. There is also Hatfield, on the other side of

the river, from which wonderful old door heads have been carried away. The

writer found one house being used as a tobacco barn on which there was a

marvelously fine door head, the pilasters being running vines with fruit and

flowers. The owner had built what he thought was a fine modern house in front

of the old dwelling and had torn out the old interior. Another house in the

same town had the walls of its parlor divided into panels by bands of stiles

and rails carved with vines. They were all torn off and burned up to modernize

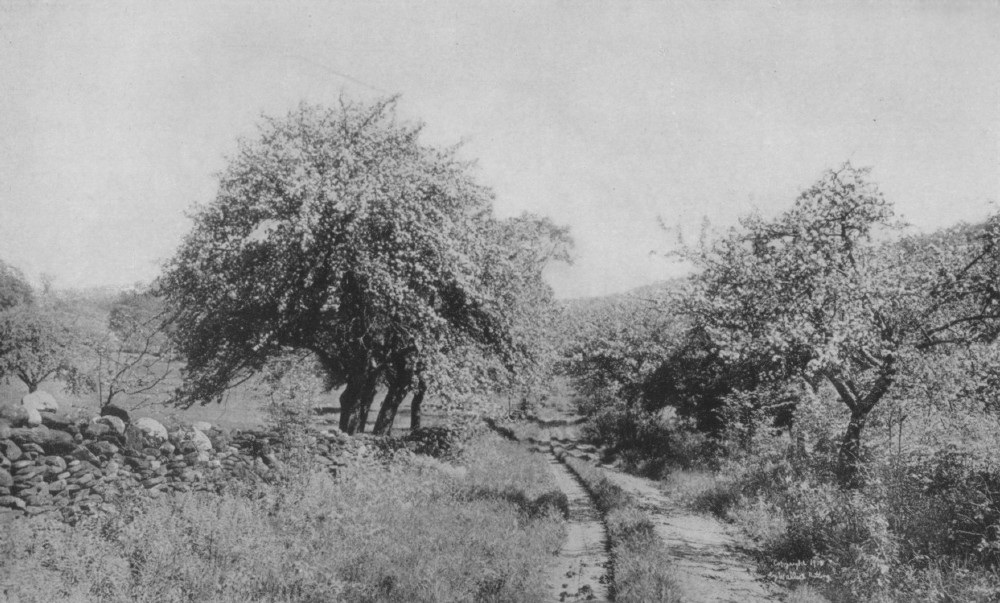

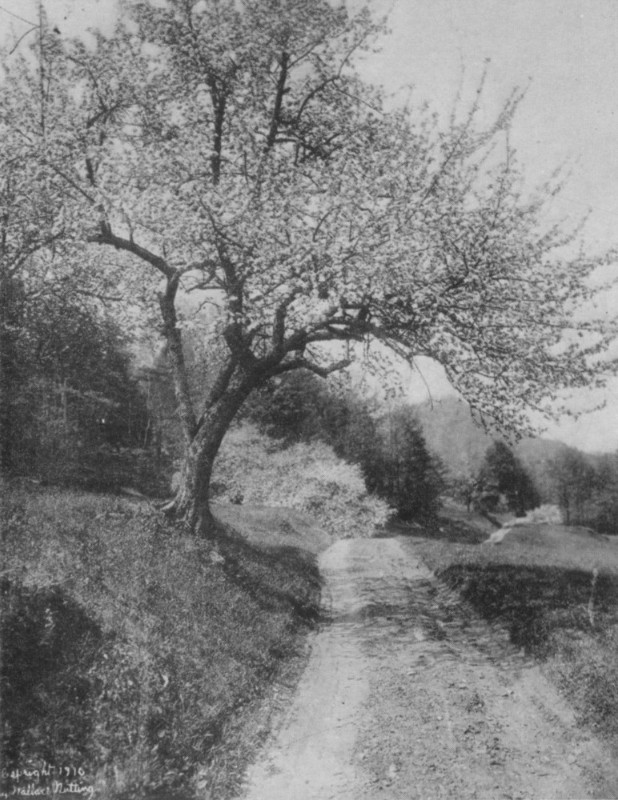

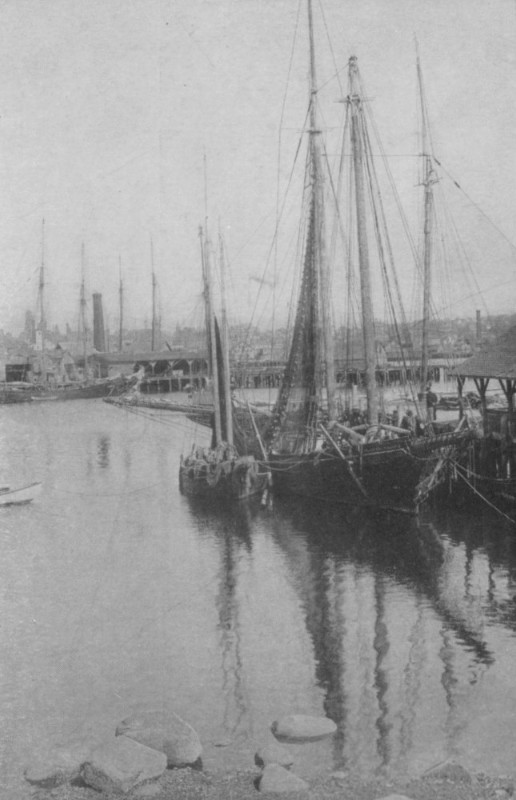

it. Oh, Fashion, what crimes are committed in thy name! Longmeadow has what so many towns lack, a feeling of the connection between the name and the place. A stretch of narrow waste land extends for the most part for many miles up and down the eastern bank of the Connecticut and one would well keep in the main north and south track. The Longmeadow street divided with a broad park strip between the two drives and graced by numerous elms and flanked by excellent houses is a sight long to be remembered. There is more of this town that is good in a straight-away direction than one will find in a long search.  PETALS IN THE PATH - LANCASTER  HAPPY VALLEY - FRANKLIN COUNTY  THE WAY TO SOUTHBORO  NEWTON MEADOWS DELIGHTFUL EXCURSIONS FROM BOSTON THE guide books are excellent for

historic sites but cannot attend particularly to selecting beautiful

landscapes. We, therefore, submit a list of various drives which are attractive

for nearly all their extent and which lead one past various beauty spots of

Massachusetts. 1. Proceeding out Commonwealth

Avenue and crossing the Charles River, in less than half a mile you reach a

fork where the main road to Weston swings right. Ignoring that fork, keep

straight on, swerving neither to the right or left through a fine wood and

Cochituate village. Immediately after passing its four corners you reach the

causeway over Cochituate Lake, an unexcelled spot for lunching under the

beautiful pines. This short causeway is a revelation of beauty on a quiet day

and a most desirable resting place. A pine grove affords a parking ground, and

the silence and seclusion are perfect. Running on from this point and

swerving only where necessary and making no short turns you enter Framingham

Center, whose old common is one of the best in this country, having no

obnoxious features in its circuit and without the intrusion of shops or ruinous

buildings. The old town house at one end and the church at the other; the fine

colonial school on the one side and the great stone or wooden colonial

residences on the other, distinguish it. After circling the common one may

resume his journey via Pleasant Street to Southboro, which is perhaps the most

English town in America. This entire district between Framingham and Southboro

and borders of some other towns is the site of the Metropolitan water works

reservoirs. One gets fascinating water glimpses, and the margins of these

lakes, partly natural and partly artificial, being neatly kept, give a somewhat

but not too emphatic park-like appearance to the country. On the way to Southboro another

causeway is crossed and one sees at Southboro a charming village group of

buildings and also a waterway connecting two lakes. The slopes toward this

waterway are thoroughly English in their gentle, well-kept surfaces, and the

residences are of a fine or unobjectionable order. One must pass well through the town

straight away to get this glimpse. One may then keep on to Northboro or swing

back through Southboro to Marlboro and there take up the Wayside Inn route to

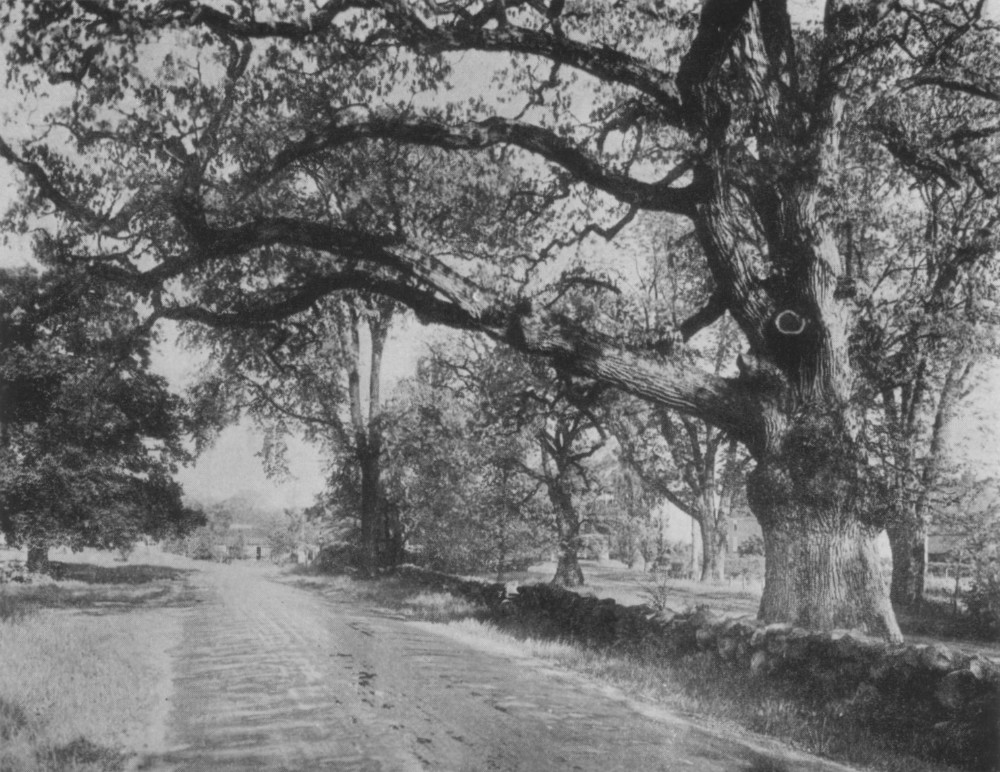

Boston. The Inn, a few miles east of Marlboro, is, in its setting of oak trees,

perhaps not equaled elsewhere. Agassiz used to say that these oaks were from twelve

to fifteen hundred years of age. The old highway formerly ran directly by the

Inn door, and it has been, happily, swung out now to one side. We may express

the hope that the Inn may be preserved in its quainter features. The gambrel

roof is considered one of the best type and has been much copied. An ancient

print shows the house without this roof and we know that gambrel roofs were

very rare before 1730, only one instance of such a roof being known. It is

probable, therefore, that if the Inn was erected in 1700 it did not have a

gambrel roof originally but that this roof is the effect of the first

improvement, which in this case we can only commend. The route thence into

Boston for some miles is marred by many roadside advertising features, but

grows better in South Sudbury and Wayland, both charming towns, and in Weston

particularly one finds a district of marvelous beauty. We refer to the good

handling of the landscape features as a setting for homes and public buildings.

One can wander all about from Weston to Kendall Green and back by various roads, or to the south, taking one road and returning by another, and can scarcely make a mistake. The most attractive route into Boston from Weston is to the right over the bridge of the Charles by which we came out. An alternate route is directly back through Waltham, Watertown and Cambridge, passing Mount Auburn and following the parkways in Cambridge by the redeemed Charles to Massachusetts Avenue Bridge.  THE BEAUTY OF THE UPLANDS - FRANKLIN COUNTY  GREAT WAYSIDE OAK - SUDBURY  THE COMING OUT OF ROSA 2. We may leave Boston by the same

bridge on Massachusetts Avenue and keep this avenue through Harvard Square,

pausing for the examination of many notable old edifices in connection with the

university, and passing on through North Cambridge, Arlington, Lexington to

Concord. There are several houses of much importance to examine in and about

Lexington and the village green there is not only superlatively interesting to

patriots but it is as beautiful as it is sacred. The town has recently bought

and to some degree restored the Buckman Tavern, an instance of very fine public

spirit as the cost was great. The old road to Concord is the more

interesting. Concord may hold the visitor for many hours with its bridge, its

monuments, its inns, its quaint and historic homesteads, its literary shrines

and Sleepy Hollow cemetery. Here is a village reminding one very much of towns

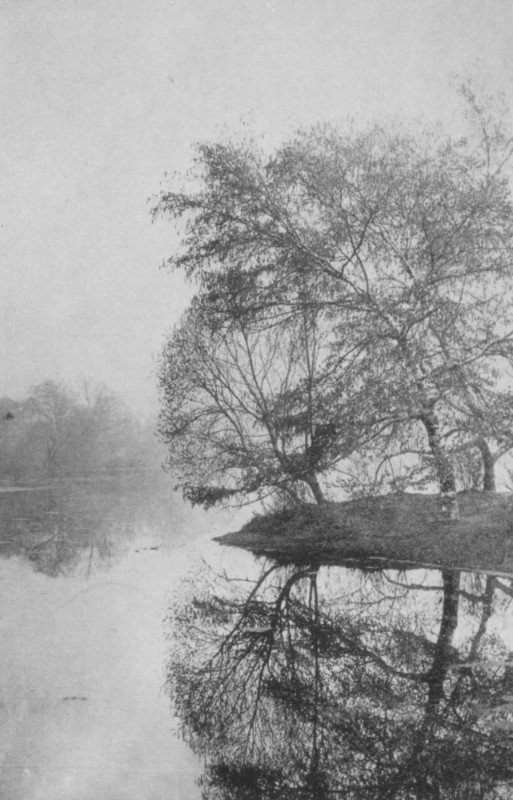

in the English fen country so far as landscape is concerned. The Concord river

in its meanderings over the meadows of the town is very seductive. One should

circle all about the village on various roads for some distance in all

directions, because in returning, perfect landscapes appear with the village in

the distance. It is a place of waters. It is a notable fact that this district

seems healthful. One hears of little malaria, and the sages of Concord lived to

a ripe old age. There is scarcely an uninteresting mile in a considerable

circuit around Concord. Lincoln is a town abounding in soft curves of road or

stream, fine clusters of elms and evergreens and stately old homesteads. One may return to Boston by

digression to Bedford, where the Stearns house on the left is a beautiful

example of its period, and thence one may go back to the Hub through Lexington.

If one cares to extend this route, although it is ample as laid out for a day,

one may go on from Concord to Acton, Littleton, Ayer and Lunenburg, thence

through Pepperell to Tyngsboro and down the Merrimac to Billerica, Burlington

to Boston, keeping the through tour route and leaving Lowell on the left. Or,

shortening it a little one may make a turn at Littleton Common or Chelmsford

and thence back to Boston. 3. A northerly drive is through

Cambridge and Medford intersecting the Paul Revere route, and northerly through

Stoneham and Reading to Andover and North Andover to Haverhill. There is no

finer hill town than Andover with its unrivaled assemblage of academic

buildings. The Academy has now taken over the old seminary buildings and added

them to those formerly belonging to the academy, and it is equipped in a manner

that would startle our English friends who think we have little in this country

architecturally. Of course, one misses the dominant ancient Gothic effect, but

there are a great number of competently erected edifices in excellent taste.

Running to North Andover and Bradford, one passes many of the early and now

highly improved country homes, some with their seventeenth century panelled

chimneys. The landscape is fair and sweet and broad-reaching to the eye in

every direction. Entering Haverhill one may go on to

Groveland and West Newbury on the way to Newburyport. On this leg of the

journey there are water reaches, and noble outlooks, and seventeenth century

houses following one another in a rapid and irresistible succession, appear, so

that one never knows which is better, the hill, the valley or the homestead.

But one does know that each is many fold more attractive in combination with

the others. We have previously referred somewhat to Newburyport and the routes

thence to Boston. 4. Taking the Dedham road from Boston one may there diverge through Needham and Wellesley to Framingham, passing many windings of the Charles. From Framingham we return through Sherborn, Medfield, Walpole to Dedham and may follow the Fenway into the city, going by the western avenues and returning by the eastern drives of that extensively beautiful district.  A BIRCH MEDLEY - BERKSHIRES  A LAST LOOK - QUINCY HOMESTEAD  QUICK WATER - HAMPSHIRE COUNTY  A SOUTHERN BERKSHIRE ROAD 5. From Boston through Massachusetts

Avenue to Mattapan, Ponkapoag, Stoughton, South Easton to Taunton is a straight

and not always very interesting route, but there are elements of great beauty

here and there. From Taunton to Middleboro and thence back through the

Bridgewaters to Randolph and Brockton to Boston is a feasible return. 6. There is a way to Plymouth by

which after one reaches Quincy one may not double on his track extensively,

from Quincy by the inside route through Accord and Hanover to Kingston. On this

route there begins to appear quaint cottage life of the earliest settlers. One

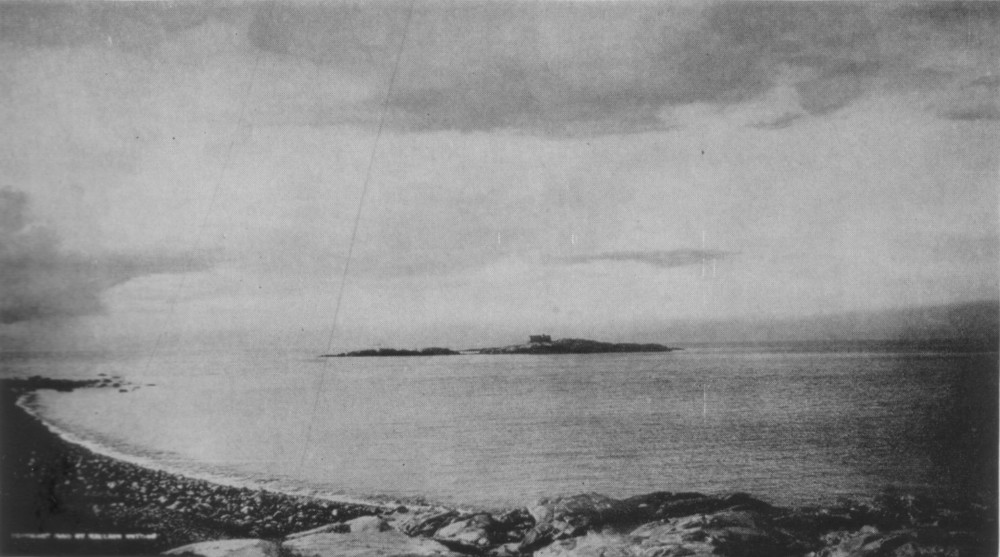

returns via Duxbury, Marshfield, Scituate and Cohasset. The Jerusalem Drive

from Cohasset into Quincy, where one meets the outgoing route, is justly famed

for its loveliness of cove and rock and island. These suggestions by no means

exhaust the principal ways of beauty that diverge from Boston, but they include

the most important thoroughfares. 7. It is almost always safe in the

touring season to diverge on any Massachusetts by-road, in the eastern portion

of the state at least. We do not enter here upon a full discussion of the

Providence road. There are fine digressions from this as from Wrentham,

Franklin, Bellingham, Milford and Grafton to Worcester or from Wrentham to

Foxboro, Norton and Taunton. The route from Providence shortly takes one into

Massachusetts, going into Seekonk and Swansey to Fall River, one of the most

beautiful drives imaginable. Or one may go directly from Providence to Taunton

over a road affording very satisfactory scenery of old houses and orchards. One

may return from Taunton to Fall River or return to New Bedford, Mattapoisett,

Wareham, back through Middleboro to Boston. It is better having made the

journey from Boston, we will say as far as Middleboro or Plymouth, to make New

Bedford a second center of touring. There are so many inlets and little taverns

and lovely water reaches that one is too hurried if it is desired to return to the

great city before night. New Bedford is wonderfully alluring as a touring

headquarters. Its museum, called the Dartmouth Historical Society, has many

features not found elsewhere. Its various shops where quaint things are sold,

its water sides and its environs may hold one for days, and there are more

agreeable accommodations in the way of lodging than formerly. 8. Tours about Worcester: Following

southerly from Worcester through Oxford to Putnam, Connecticut, one comes, near

Webster, upon the lake with the long name,

Chauggoggagogmanchauggagogchabunagungamaug. What this word means is said to be

a thousand bays, but we do not guarantee the correctness of the etymology. It

means to some people a stutter if not worse, but it is easy if you know how. Returning to East Village east of

Webster one may pass to Douglas, East Douglas, Sutton and Millbury back to

Worcester, but this return route is not a main thoroughfare and one must be

prepared for concentrating his enjoyment on the streams and ponds and back country

in general. The main route from Worcester to

Providence passes through Grafton, Northbridge and Uxbridge, following the line

of the Blackstone river, which, while said to be the American stream most

thickly studded with manufacturing towns is, in spite of that, often beautiful.

Arriving at Worcester, if one does not care to keep on farther, one may cross

over to Bellingham and thence back to Worcester by Milford, Upton and Grafton.

The east and west route from Worcester is the main Boston and New York

thoroughfare. We have covered this route going west from Boston as far as

Marlboro. The slopes from Worcester into Shrewsbury open up fair prospects and thence down to Northboro there is much of interest. This road, however, is swarmed with vehicles and is more like a trunk line railway than a quiet touring journey. Westward from Worcester by the same main line one finds at Leicester a high and attractive village. One is now in the highlands of Worcester county, the backbone of the central part of the state. It is a general elevation of the Whole territory. There are broad and smooth fields stretching away to a great distance. At East Brookfield one may diverge to North Brookfield, a very pleasant journey, and a little west of West Brookfield one may turn north to Ware and its charming river valley, coming back to the main road at Palmer. The route from West Brookfield through Warren to Palmer is essentially a region of little mountains, each side of the Quaboag river, a stream which offers us many a shimmering reach of placid mirror and many a rapid of herring-bone water.  BUCKLAND  THE SHOCKED CORN - MILLIS  OAK CURVES - MIDDLEBORO  A SAUGUS OVERHANG HOUSE The hill crest and cloud effects

through this region are not enough enjoyed, as people on this main road are

always going somewhere about as fast as they can. But when the mists flirt with

the hill crests, now touching, now withdrawing, and when the sunlit slopes

change from green to brown to pink and to purple in the westering light, one

should pause and consider that this heavenly vision is for him. A farmstead nestled on a high slope

and looking out over the splendors of the valleys and the hills and the

changeful sky supplies a joy always present when man nestles in the bosom of

nature and thoroughly adapts himself to his surroundings. These hills are as

gorgeous as the Berkshires and are no less beautiful. In fact, some vistas

which open on this drive are, when we review them in memory, a most sweet

reminiscence. From Palmer one may strike back

through Brimfield to Southbridge and thence through Charlton to Worcester. This

route is over the higher hills and at Brimfield one finds a little rural

village that appeals to the imagination. Also from Brimfield opens a new

southerly route into Connecticut which when completed will be a more popular

way than that now usually followed through Springfield, because it is far from

the beaten track and one does not, all the way from Southbridge, coming from

Worcester, or Palmer, whichever the point of departure, pass through, until he

comes to Hartford, anything larger than a rural village. There is another short journey of

interest from Palmer to the Monsons, though it is better, perhaps, to return at

the end of the good road, or one gets into a country too rough for motoring. Westward from Palmer to North

Wilbraham, if one diverges to Wilbraham and thence to Springfield, the road is

not so jostled and the old town of Wilbraham is attractive not only from its

fine trees and roadsides but from its academic traditions. We have indicated return journeys to

Worcester from which we should take still another journey. For instance, going

back through Palmer by the main route will furnish a very good day's excursion.

Going out again from Worcester to

the north to West Boylston we come upon the great Wachusett reservoir. We

believe this is the largest lake in Massachusetts. If one chooses to skirt the

lake from West Boylston to Clinton, down through Boylston Center back to the

starting point, he will see a variety of landscape, all, as it were, made by

man, since the lake contours and the water reflections have entirely changed

the scenery. As one leaves Clinton one should

pause to go out on the great dam, the noble and massive work of engineers,

which did not forget to be beautiful. If one chooses to keep on from West

Boylston north through Sterling to Leominster and Fitchburg he will find a

pleasurable journey. He may then go from Fitchburg to Athol and thence back

through Barre to Worcester. But this Worcester-Athol route deserves very much

more attention from the lover of beauty. Beginning from the Worcester end two

stretches are open, one through Paxton and the other through Holden, the two

roads meeting at West Rutland. That through Paxton has a fine stretch of

woodland. That through Holden and Rutland is very high and sightly. Through Colebrook Springs to Barre there are small water glimpses of unusual beauty, and at the foot of Barre Hill is one of the best of that kind. A wood road of perfect beauty is part of this journey. From Barre into Athol is a road probably second to none in the exhilaration of its long high stretches over the highlands. Petersham is a summer resort and an old-fashioned village located on the back-bone of the state. The soft, long, sweeping slopes from each side and the far-reaching views give one something the same impression as on the journey through Palestine north and south.   WELLESLEY WITCH WATER NANTUCKET GOSSIP  A PEEP AT THE HILLS - CHARLEMONT  A GLOUCESTER PETER There remains to us one more

excursion, at least, from Worcester which should not be omitted: that to

Wachusett Mountain by Holden and Princeton. Shortly beyond Princeton Center as

one enters the mountain road the fair prospect of the state eastward to Boston

and the sea seems to show one a map in relief of a vast territory. To our

thought the region around Wachusett is destined sometime to be more highly

appreciated. It is the nearest mountain peak in Massachusetts to the great

centers of population, and is, therefore, the only spot inland for many miles

around, where one can be certain of mild summer air. Many cross roads from this

region, while given no attention on touring maps, are yet attractive. One can

approach Princeton from the east through Marlboro, Hudson, Bolton and

Lancaster. Between Sterling and Hubbardston, going directly through Princeton,

one finds in the laurel blossom season hillsides which are solidly covered with

its flowers. Before leaving Worcester one ought to have a day or two about

Lancaster, which we believe to be the town containing more great trees of many

varieties than we have elsewhere seen. An oak, a buttonwood, about as large as

any, a maple, an ash, and an elm of surpassing diameters were all there until

lately, when the Queen Elm went down in a storm. The tree was thought to be the

largest elm known in our country. Many years ago we placed a horse and cart

behind the tree to hide them when picturing it. The rear of one wheel tire and

the tip of the horse's nose were all that were visible, although the animal and

vehicle were arranged not endwise but crosswise to our vision. This tree had a

circumference exceeding twenty-six feet at one's shoulder, and of it Holmes wrote:

"Where

the broad elm, sole empress of the plain,

Whose circling shadow speaks a century's reign, Wreathes in the clouds her regal diadem, A forest, waving on a single stem." It is said, by the way, that Holmes

used to carry a string in his pocket and slyly measure the elms in England, and

that he felt some chagrin to find that they slightly exceeded the noblest he

knew in America. He might easily, but for poetic limitations, have extended the

century to three, which is about the probable life of the largest old

specimens. The forest effect which he so finely brings out may often be

observed by the springing of a half dozen branches almost celery like, and

giving the impression of a woodland in themselves. In some pasture also we find a maple

with an almost perfect demidome top and a foliage at the base about seven feet

from the ground. This curious formation on the lower foliage of trees in

pasture lands arises no doubt from the browsing of the cattle. It is seen in

California to perfection on the sharp slopes where grow the live oaks whose

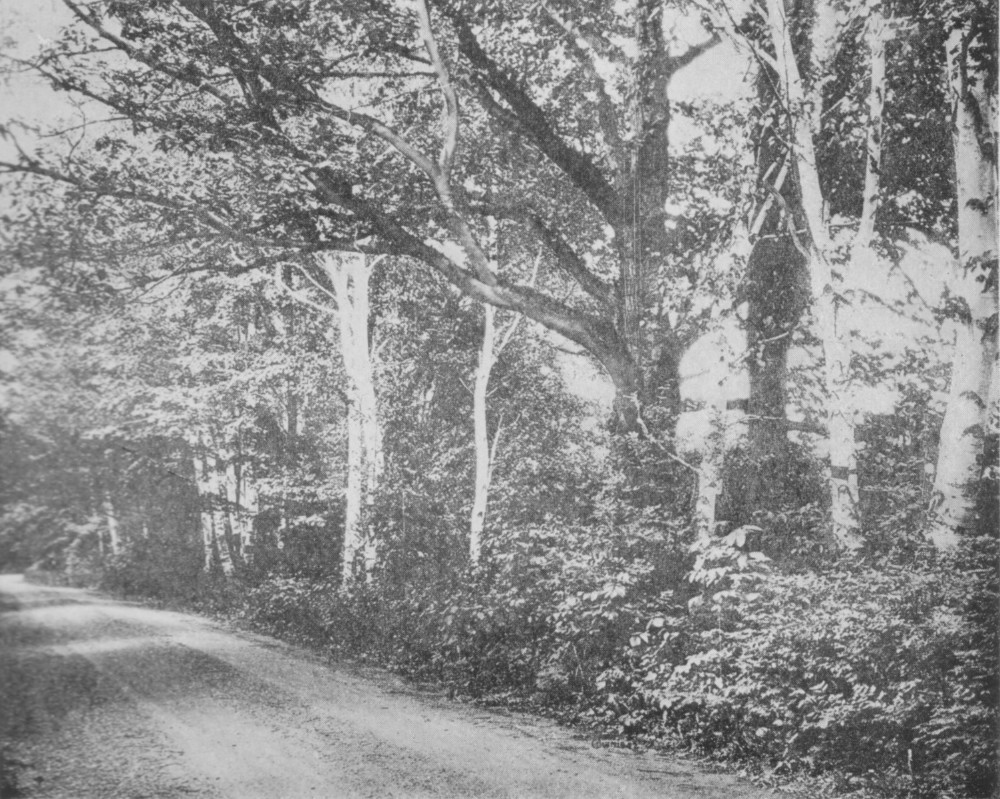

branches will parallel the hillsides downward and upward almost precisely. In North Lancaster the Seven Bridge

Road is a wonder of elm foliage. The trees are self planted and at places grow

like a gigantic hedge and at another point opening sufficiently to permit the

development of massive columns. The Thayer family were pioneers in Lancaster in

beautifying the landscape in a broad way, and the region for miles around is an

exquisite example of country life in America at its best. These remarks include Harvard, whose

orchard ridges are marvelous in their beauty, so much so as almost to be

unique. Bolton may be included in this same orchard neighborhood and Sterling

as well. There are considerable regions in Massachusetts which, according to the common phrase of the farmer, are fit only to hold the world together. It would be gratuitous to point out such districts, but we wish to puncture the cockiness of the westerner who thinks slightly of our Massachusetts farms. The writer has journeyed in every state of the Union, and lived in two western states, several years in each. He has yet, however, to see any fairer farming tracts than many in Worcester county. The same remarks might be made of districts in Essex, Hampshire and Franklin counties. There is an abundance of scrub oak and thin gravelly soil here and there in the rough back country of the state. In such regions the dwellings become ruinous and the number of inhabitants consistently shows losses in the census. These so-called abandoned districts are much talked about east and west. The fact is they are of small importance considered in a broad way. Their total number of inhabitants is small, and if their churches are abandoned it is because there is no one to attend them. It is obviously absurd to consider running state roads through all such districts. The land is gradually being abandoned to the encroachments of forests. This is as it should be. It is a natural water shed and wood reserve country. A state utterly fertile everywhere could not afford woodlands.  THE WAYSIDE INN APPROACH  A DEDHAM BANK  A NEWTON OCTOBER  OLD CHESTNUT STREET - SALEM A GAMBREL CORNER 9. Springfield, Holyoke or

Northampton may be chosen, as one's tastes suggest, as a center for exploring

the Connecticut valley. From Northampton to Holyoke, to South Hadley Falls,

South Hadley, the Notch to Amherst and back to Northampton by way of Hadley

includes a range of meadow and hill so agreeable that one could not regret the

tour. Amherst is in a fair open plain. The river cutting the Mount Holyoke

range 'affords the only contrast in the region between mountain and stream. The outlooks from Mount Tom or Mount

Holyoke are of an unusual character in America, resembling more the Hudson

highlands than most of our viewpoints, because of the river below. Such views

as these are not to be seen in the White Mountains. There we have the

continuous ranges of other mountains, here the broad and fertile valley of the

Connecticut not surpassed for fertility nor, in its specialties of culture, by

any region, are spread below one as well as the tortuous windings of the river.

The journey through Northampton

through Williamsburg and the William Cullen Bryant region of Cummington to East

Windsor, thence to Dalton and Pittsfield, is one of the newer mountain

thoroughfares which were discovered to Americans and now available for their

convenient inspection, districts capable of providing a rest region for the

future of teeming America. There are one or two offshoots from the Jacob's Ladder route as one goes west from Springfield, the great and in many ways delightful city of western Massachusetts. The route to Westfield is through a plains country, but at Woronoko we reach the windings of the hill roads. There are digressions here. There is another one from Huntington to the north through a region of wonderful possibilities and present splendors of hill and valley. At Chester one may climb again to the north from a main road over the heights.  A CAMP - QUINSIGAMOND  A MANCHESTER BIRCH DRIVE  THE TIN PEDDLER  THE DOCKS - GLOUCESTER  A STERN SHORE - GLOUCESTER  A LITTLE HOMESTEAD - SHREWSBURY  EAST HAVERILL  MEERHOLM - NANTUCKET Springfield is sufficiently far from

Boston to have a thoroughly individual development. Its public buildings vie

with those of Hartford. One may possibly question the appropriateness of the

Italian architecture in New England, but its beauty considered by itself cannot

be challenged. Springfield often considers itself, we presume, much as Los

Angeles in California, as the natural center of its state. There is a virility

and an enterprise and an intellectual development, such that the city has

claimed and been accorded for generations to be the sufficient source of all

urban influence, that is needed for many miles around. It has taken on, late

years, the character of a metropolitan center. The total population near or

tributory to it has risen to pretentious numbers. By its strategic location and

its alert and energetic leadership it has started on its career like some great

Western cities to claim national prominence. The province of our book does not

permit us to dwell extensively on urban matters but we must at least pause to

rejoice in the vigorous life and prophetic future of Springfield. THE OPEN FIRE MANY persons still know by happy

experience the soothing, dreamy effect of an open fire. Our word "hearth" goes

back to the roots of our language. Even persons of very active temperament can

gaze at the witching blaze of an open fire and be content. Its play of color

and fantastic shapes, its spitfire and its glowing embers are invitations to

dream. Back of this, of course, lies the completest chain of heredity known to

human beings. The oldest of all sentiments has grown at the hearth into human

consciousness. Warmth and protection, a sense of home, the memories of every

progression of age in a single human life and in all life are all gathered into

the mystic web of unconscious memory. From the hearth came the savory dish

after a day of fierce battling with wild beasts and wilder elements. The

earliest waking knowledge and dawning affection were born at the hearth side.

The boy there learned the lore of his tribe. There the family councils were

held. In their old age our fathers sat

huddled in the chimney corner, fondling their grandchildren upon their knees. The hearth was the focus of the

house. In its modern significance there is a fine flavor. It was the fountain,

the center, the core of life. It was the glowing source whence emanated all

humane civilizing currents, and there at last our fathers were gathered to

their fathers. Let us not break that priceless

chain but maintain one room at least where a little open fire may call us about

it at evening. Thus we shall keep the connection with that vast mysterious stream

of hopeful humanity which was and is and is to be. Thus we shall have unity

with history and our sympathies will be warmed by this curious, wondrous

potentiality, — a human life, born in mystery, existing by struggle, passing

into shadows but big with gleams of a far-reaching, wondrous, rising future. The fireplace is shown in this

volume in many of its aspects. We have in the huge early form its rounded back

and plastered wall as in the parlor (p. 80). Little recesses were constructed

in the rear ends of the fireplace to hold the tinder and keep it very dry. A

seat was sometimes actually built into the end so that on chilly days when a

bit of fire was needed for the aged they might sit in the chimney corner. The somewhat later kitchen interior

of the Revolutionary days, was a storehouse of every necessary household

utensil. Our ancestors did not seek to hide the culinary utensils but displayed

them with pride. Their open dressers and walls, hung full of iron spoons,

forks, ladles, skimmers and skewers, were almost an education in themselves. As plenty was secured, our mothers

of five generations ago embroidered by the fireplace with their pointed frames

capable of being swung as they willed. In the backs of the fireplaces were great ovens built bee-hive shape as in the Hazen house, Haverhill, always called the Garrison House. It has two such great ovens each swelling into a closet at either side of the fireplace. These ovens had no separate flues but the blaze kindled in them rushed out of the door and up the chimney. When they were well heated they were raked out and the baking was done by the process of absorbing the effects of the previous heating. This was the true fireless cooker. Such an oven would keep warm twenty-four hours and remain hot for twelve.  BLOSSOM LANDING - WILLBRAHAM  HUNTER'S ISLAND - COHASSET  SHADOWS ATHWART - LANCASTER  A NORFOLK FARM LANE On bitter days of winter the work

was done near the fire. The apple paring and the pie making amused the small

child and stirred the sense of domesticity in the sturdy yeoman who came in

from his labors. The fireplace of the earlier time

had an arch above it to serve as a foundation for the hearth in the chamber

above (p. 176). In this, the Cooper-Austin House at Cambridge, said to be the

oldest dwelling in that city, the pie is being taken from the old oven. The cat was a happy addition to the fireplace.

She gave the last touch of domesticity and was almost as important as the

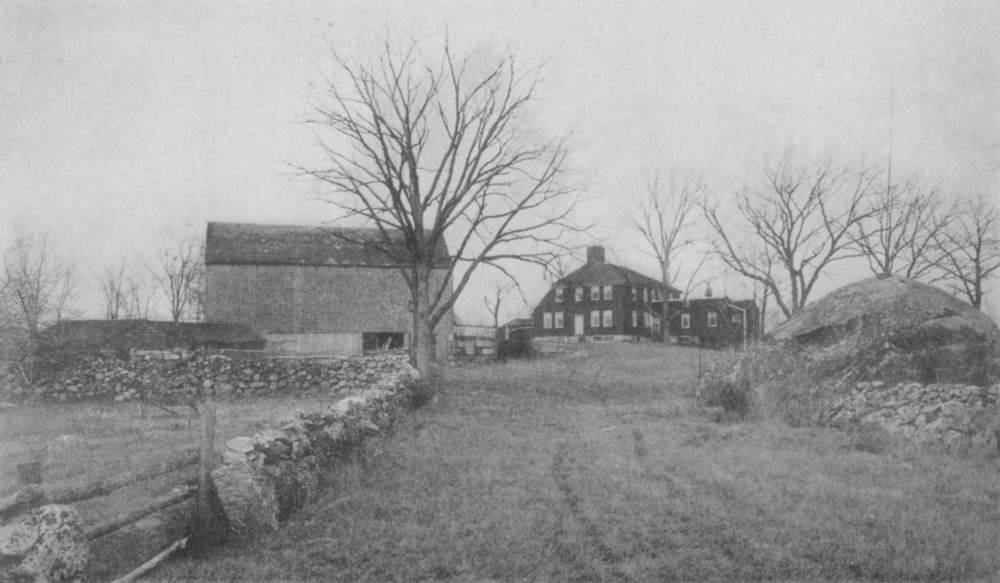

cradle, as a part of the composition (p. 156). This fine old place, the Gates

house, near Framingham Center, is nestled under the hugest and most beautiful

elm anywhere known. It covers the dwelling, the highway, the lawn, the walls.

What a contrast to the characterless numbered dwellings of a city street which

have no possible distinction. In an old house like this all the timbers know

one another and their owner. He has inspected the stones of their foundation.

He has remedied incipient decay. He has protected their roofs against the

storm. He recollects the history of the changing generations who have dwelt

there. Every room is a monument of a great event. Every chamber knows the going

and coming of life. In the parlor weddings have occurred for generations. There

is not a nook but is redolent with the comedy and tragedy of life. The old home

has made good its place in the world. The generations have gone past in their procession

over the highway. The setting of the home, every slope, every path, every

gable, every arching curve of branch above, every stone in the wall is part of

memory's picture. Life is enriched and ennobled by such a homestead. One cannot

say that all generations will be noble born amid such surroundings, but it

would be folly to ignore the stimulus to patriotism that such a training must

supply. A fine conservative spirit which desires to retain the old homestead

and its furniture, although both are marked by honorable scars, is one of the

better aspects of civilization. At a little later time or in the

smaller rooms diminutive fireplaces were provided with their interesting

mantels where if at all, appeared the decorative tastes of the builders. In

such handsome rooms the mistress entertained her friends at "Tea in the

State Chamber" (p. 76). In this, the Lee Mansion, Marblehead, we have a

very noble example of the taste of the best decorative period. Here, panelled

to the ceiling, the parlor is reminiscent of the homes of England. It is past

comprehension that a few years ago such places were utterly neglected. It is

worth while to recall that this Lee Mansion, standing among the four or five

best houses of the North, was sold at auction for $5000, and had not a man of

vision in Marblehead happened to drop into the metropolitan office where, far

from the dwelling, the property was being sold, it would have been lost to the

public. In fact, most of our fine early houses have been thus lost and are now

beyond recall. The writer could narrate by the hour similar instances of

carelessness and neglect. The King Hooper House at Danvers (p. 96) has been

saved to the family which has for a long time held it. Its rooms are also

panelled. Aside from the end porch it is nearly as it was, its wonderful rooms

a monument of a well-balanced and cultivated coordination of dwelling to

inhabitant. On the fireplaces such as graced the

period of 1730 to 1770 in the parlors it was common to use a border of Dutch

tiles. The hearth not only in the finer, but in the larger and constantly-used

fireplaces was usually composed of brick tile about seven and a half inches

square and laid, not as they are now laid with wide seams, but close together.

These old tiles are now very much sought. We recall one happy instance where a

seeker about to erect a home in an early style purchased a place for removal,

the cellar of which he found completely paved with these tiles. The side and back walls of the fireplaces were always ordinary brick. Pressed brick never appears and in the effort to copy, the use of such brick is clear evidence that the feeling of the old fireplace is not understood. Fire brick were not used on the back, at least not at an early period, and very little anywhere. The continuous disintegrating process of the blaze against the rear brick was overcome by inset fire backs of wrought iron in wonderful old molded forms. Some made at Saugus are still in existence. Such a fire back was discovered in a room in the Winslow house at Marshfield. Sometimes in the earliest period plain sheets of iron were used.  SEDGES AND ELMS - NORFOLK COUNTY  AN OAK-BIRCH ROADSIDE - LENOX  HAZY BIRCHES - BOSTON  STUDIOUS MAID - ANDOVER Mantels are not found, or found with

extreme rarity, in the period before wainscoting came in, about 1720. Before

that time the chimney tree, as the great stick was called, supporting the

bricks over the fireplace, was frankly exposed. This stick was often of oak;

frequently of bog oak which would never catch fire. Instances are known of

chimney trees twenty inches in depth. The inner side of this great lintel was

hewn away on a slope to encourage the smoke to ascend. Artists of imagination have shown us

in mural paintings the beginning of the civilized state symbolized by a fire.

The Greek legends regarded fire as stolen from the gods. It is, of course, the

first and probably the most powerful stimulus of the human intellect. At first the fire was built against

some cliff shielded at least on one side from the wind. Little by little it was

shut in more and more. We think of the chimney as a very ancient institution,

but English literature contains notices of the first chimney on the houses of

the nobility as curious ducts to carry up the smoke. Before that time the smoke

ascended, as among the Indians, through a vent hole in the roof. There are

ancient creosoted beams today in many an old English dwelling against which the

smoke of early generations rolled. From such beams hams, venison or pork were

hung and without any other special attention, smoked meats were obtained. The writer visited in Alaska the

remarkable village where Mr. Duncan gathered the coast Indians and taught them

how to live by adopting only those devices of civilization which seemed necessary.

His own residence consisted of a main room the center of which contained a

square area of sand. Above a tunnel-like canopy, a kind of suspended chimney

gathered the smoke and conducted it through the roof. It preserved for us a

lively illustration of historical development. Many of the fireplaces in the

old world filled the entire end of the dwelling. There is one such in Rhode

Island, outside our scope. Thirteen feet is not considered a remarkable spread

for a fireplace three or four hundred years old. In that period stone was used

chiefly, but it was roughly faced. We cannot enough deplore the thoughtless fad

of using round field stones not only for house walls but for fireplaces. No

such construction is ever found in good or even simple American dwellings

except possibly in the remote and crude Appalachian regions. In some villages

people seem to have gone pebble mad, setting up flimsy posts, fences, porches

and shaky chimneys of such small boulders. The true fireplace shows an effort

at shaping stones for their use and it is this meeting of man and natures the

adaptive and creative instinct, which gives old homes their charm. The earliest fireplaces have a depth

of three feet in some cases and not a few are two and a half feet from front to

back. The vast logs were sufficient for the bitterest winter, but as time went

on a second and third fireplace of brick is often found constructed within the

old one to contract its dimensions and render it easier to supply fuel. Baking was done not always in the

oven, which was a weekly event, but sometimes daily in cast iron Dutch ovens

with covers of the same material in which bread was baked "between two

fires" That is, the dish was placed upon coals and coals were heaped above

it. Rapid action was had and a delicious aroma secured, impossible in modern

methods. The ancient turnspit for roasting

was laid on hooks on the andirons. In a well-equipped fireplace there were

three series of hooks rising one above another to accommodate the size of the

roast and the conditions of the fire. A pulley connected with a minute belt to

a weighted jack on the chimney tree completed the outfit, as in the little

sketch called "Christmas Expectancy" opening this book. It was later that the jack supported on a tin rounded screen came in. Such an affair would have been impossible to have used before a great fire. The date of this arrangement was late in the eighteenth century. As the use of the jack was more or less bothersome, boiled dishes were the more ordinary diet, and where a weighted jack was missing it was often necessary to roast the boy while he roasted the meat. So the great pot in which the meat was stirred up by the tormentor, a fork of ominous size, was hung from the lug chains or later on from the crane.  THE NASHUA ASLEEP - LANCASTER  DISAPPEARING IN BLOSSOMS - FRANKLIN COUNTY  JANE OF NANTUCKET  A BERKSHIRE POOL Beautifully spiraled toasters, now

so much sought, held the bread upright on the hearth. Revolving broilers with

serpentine grills and all manner of fantastic shapes were used for steaks.

Birds were spitted and revolved from a swivel hook one of which we show. The

hob, so common in England, was scarcely used, at least in the North. The

English fashion of swinging a diminutive crane from a high andiron, a most

picturesque and attractive device, we have not seen as yet in this country. The great mass of the fireplace,

when thoroughly heated, acted somewhat as the huge porcelain German stoves of

this generation. The heat was retained and diffused through the night, and

though the frost line might approach within several feet of the blaze the room

was fairly well tempered. An ideal modern dining room is

secured by the restoration of such an old kitchen retaining every quaint and

ancient feature with dressers and open shelves and wall hooks to exhibit the

pride of the housewife. |