|

|

||

| Kellscraft

Studio Home Page |

Wallpaper

Images for your Computer |

Nekrassoff Informational Pages |

Web

Text-ures© Free Books on-line |

|

American

Cookery

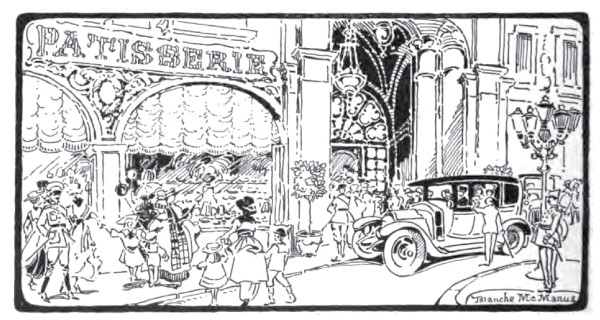

VOL. XXII DECEMBER, 1917 No. 5 [page 359-365] Blond Pastry of the French Patissier and the Brunette Pastry of the Italian Pasticciere By Blanche McManus

For the reason that France and Italy are the two great pastry making and pastry eating nations. Before their achievements the efforts of all the rest of the world shrink into insignificant proportions. Even the genius that launched the most toothsome of all pastries — the great American pie — is hardly placed in the running in this competition, because of the fact that pastry, as defined à la Francaise, or àlla Italiana, comprises an almost interminable list of sweets that have broken out and spread far beyond the frail barriers of pie-crust, and have absorbed into their serried ranks a complicated variety of sugary morsels of delight, whose nomenclature alone would Form a bulky dictionary. In France they are still grouped under the generic name of patisserie, and in Italy as dolci. Their consumption in each country is enormous, playing the sweetening rôle in the Latin's gastronomic day that candies do with us. Indeed the profusion of our delicious candies is quite unknown with them, and with the exception of very high-priced chocolates offer little appeal or variety, while the big lucious cake, as we know it, practically does not exist. Fancy candy being censored out of the American's food program for two days each week, and you can imagine the consternation that prevailed in Europe when the war régime of unsweetened days went into effect. Tuesdays and Wednesdays in Paris are now fast days for the diminutive tartlettes and petits gateaux, the days considerately selected by the thoughtful French food censor as being those the least liable to disturb the sweet routine of French life, which rises to its high-water line on Sundays and Thursdays, the two French family holidays, when the pastry shop becomes the family goal. The French consider anything in which enters butter, milk or eggs as pastry, and so the war regulations cut off the sales of soda biscuit and corn bread sold at the few Paris tea-shops catering especially for Americans. By an ingenious subterfuge a sort of pastry, or tartine, came to the surface these fast days which did not fall under the ban — a sandwich of a sort, with a pastry upper and lower lid and a streak of jam or jelly or confiture in between. It was, however, but a poor substitute and as ephemeral as the Minister of Food Supply, who promulgated the law against a full pastry week, and who remained in office but a few weeks. In my block in Paris there may be counted five patisseries, which evidences their popularity. French fashion is to eat pastry on the spot, standing. The quantity of it bought to be taken home is relatively small. One chooses her own assortment from the stock ranged temptingly in rows on white metal platters, and helps oneself at the same time to a small plate and fork from a pile close at hand, absorbing the chosen delicacies as best may be, among the struggling throng, all intent on helping themselves in the same fashion. Usually there are a few small tables in the rear to which one may retire with a heaped up plate, but never really enough of them to accommodate the crowd. Each keeps tally of the pastries actually consumed and pays her account to the cashier with never a query. Nevertheless the clerks apparently have an occult way of keeping tabs, and mistakes, intentional or otherwise, seem never to occur. Diminutiveness is the principal characteristic of all French pastry, little thimblefuls of deliciousness, when made of good materials by a good patissier, and unexcelled in their particular species, of which there are three: fruit tarts and tartelettes, pastry à la creme and gateaux mousseux, colloquially mentioned as petits fours, deriving the name from the special oval oven in which they were, originally baked. The tartlette may be considered the pet delicacy of the French, and the most typical, hardly larger than a dollar, of flaky crust in which is nestled the half of an apricot, a quarter of a peach, as few as three plums or as many as four cherries, over which is poured a hot syrup of fruit juice and sugar, thickened in many cases with gelatine. From its excessive stickiness, one suspects the presence of a drop or more of the sweetened liquid which the French are so fond of putting into their sweets and which they buy by the bottle and dash over things with a liberal hand. The tartelette is made of either dried or preserved fruits, but the fresh fruit, cooked to this extent only, is considered the most récherché, and as it only makes a good mouthful does seem a little dear, though the price be but the equivalent of three cents. The tarte is but a larger growth of the same, rarely attaining the size of an American pie, the largest being about a third of the circumference of our classic pastry. Its price ranges from fifty centimes to five or six francs, say ten cents to a dollar.  PARIS

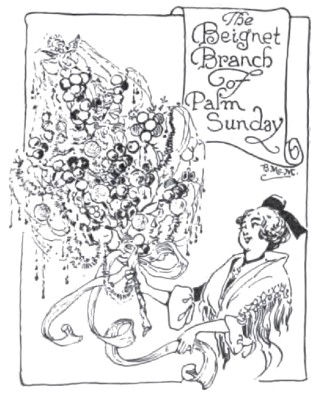

PASTRY-DAY, THURSDAY

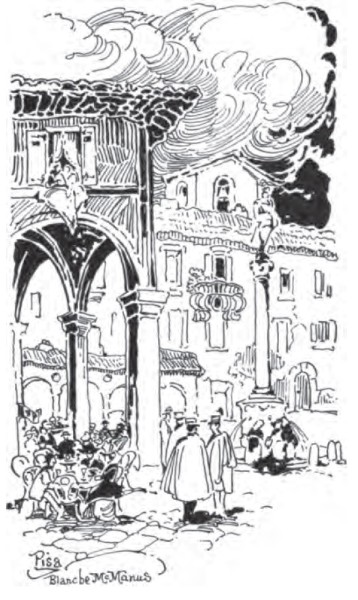

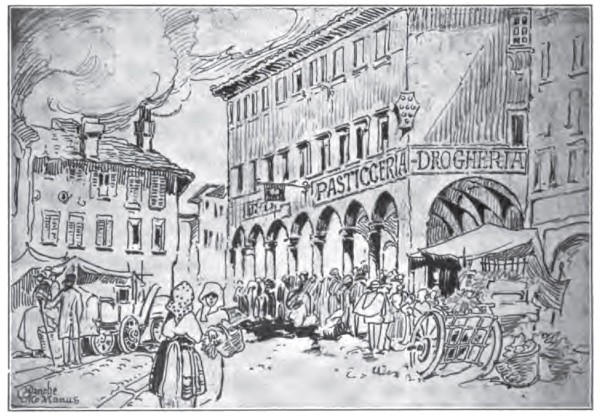

A more ordinary form of fruit tart is made, one might say, by the yard, in big oblongs brought in on a board covered by a napkin and retailed in three sou slices. It is invariably of dried fruit with the same syrupy glaze. It is not, however, considered in the same class as the before mentioned, but rather as a plebian relation only, as is also the chausson, a turnover, usually with a scant filling of dried apple. Another genre is something on our cheesecake order, with filling of almond paste, and macarons, from Nancy in the war zone, which are made, or supposed to be, of almond flour, but one suspects that sometimes it is chestnut. Again there are the popular cornes à la crême, cornucopias of pastry, in ingenious spirals of varying lengths, filled with cream stiffened and whipped up with the white of egg. As sweet cream, as we know it, is not to be had, such thick cream as is used is of a slightly sour, acrid taste that the French seem to like. Eclairs come next in popularity, chocolate and coffee flavored, but in nine cases out of ten the latter. The white glazed eclair is rare. The creamy custard fillings of all the gateaux mousseux are usually guiltless of flavoring of any kind, or the flavoring is so infinitesimal as not to be noticeable. French taste does not seem to require this aid, and with exception of vanilla, used in the form of small gratings of the vanilla bean, they fight shy of any kind of flavoring, above all in liquid form. However, extract of coffee is so universally employed that it may be said to be the classic French flavor, and the gateau moka the cake de luxe. Icings are but little used but the moka extract is mixed into a thick cream with butter and confectioner's sugar and used as a rich glazing as well as filling. These are the cakes in larger form which are the usual birthday or holiday cakes, on which occasions the art of the patissier decorates them with names, mottoes and various forms of salutations, worked out in various colored icings and further enhanced with flowers of crystalized fruits and silver and gilt ornaments. As for simon-pure layer cake of the American species there is nothing at all ever seen at the French pastry cook's, or if found it can be accepted as a foreign graft not in the least indigenous. The same ingredients of the moka cake go to make up the holiday season Buche de Noel, or Yuletide Log, so called, because it, is made in the form of a miniature log of wood, the brown moka pate imitating the bark of a tree. It bears usually some sugary inscription such as "Bonne Année", or even the words: "Buche de Noel". About the end of the first week in January the French pastry shops display another seasonable cake, the traditional gateau du roi, the Epiphany cake that commemorates the visit of the Three Kings. It is really more of a species of sweetened bread, in which are baked little symbolic images which add to the amusement of Gateau du Roi supper parties, a custom especially of Southern France, where traditional observances most flourish. There the Epiphany cake is called fougasse, and is made in the shape of a crude Maltese cross, and of more humble ingredients than usual, in which olive oil takes the place of butter or lard. In southern France, too, the pastry cooks turn out a curious kind of wedding cake of towering form, composed of tiny two-inch balls, or beignets, made in a puff-ball fritter style, "glued" together with a coating of hot melted sugar which ultimately cools into a glassy pinnacle in which the puffs are imprisoned. The whole is surmounted with a tiny white sugar bride in a real tulle veil and decorated with the usual bridal symbols of loves and doves. It is a cake which has rather to be picked to pieces to be eaten, than to be cut. These puff-ball fritters serve for another extraordinary confection in pastry that appears once and again in various parts of southern France the week before Palm Sunday. From a small blanch of a tree or shrub all the leaves are stripped and the pastry balls with their glassy coating stuck on the depending twigs, together with candied fruits, oranges and apples, even little toys; while over the whole are draped garlands of tinsel gilt and colored streamers. It has the effect of a weird sort of little Christmas tree, and is carried to church by the young people on Palm Sunday in place of the conventional palm branch or box twig as is otherwise customary. As these confectionery palms are often several feet in height the effect of numbers of them being carried through the streets is bizarre.  The most sought of all French pastry sweets are the tiny délices, served in frilled paper cups of white or gilt or silver that contain the sugared imitation of some natural fruit, such as a strawberry, a fig, cherry or a slice of orange, or a grape filled with some liqueur of various flavors and strengths. Though really of the confectionery class, they are served and consumed as are the petits fours, and are particularly in vogue at functions where refreshments are served standing at a buffet, as is so general in France, as they can be handled with impunity by daintily gloved fingers. Plum cake, if you choose to class it with pastry, since all pastry shops sell it, is found everywhere in Paris these days, but it is frankly an imitation of the imported English variety and a long way behind the real thing. American cake and pastry is found only in two or three soi-disant American tearooms and, as far as they and it goes, is a satisfactory enough substitute, the chief criticism being that it is under flavored and not as "rich" as appears best to suit the American palate. One's first impression of Italy is that the Italians are pastry-mad, and surely spend most of their waking moments in the pasticceria. Pastry shops are everywhere and are apparently crowded at every hour of the day and a good part of the night. They are as plentiful as old masters and enjoy, in some instances, quite as much repute and often are far more interesting. On the stage set by the big pastryshops of Florence, Rome, Venice and Naples pass the real "Revues" of Italian manners and customs. Their rôle is much more important even than in the life of the French, because the Italian pastry-shop with its feminine clientele is also often the adjunct to the café. The place of the French café is more than filled by the pasticceria, which not only makes and sells, to be eaten on the spot, pastries, tea, coffee and chocolate, ices and creams, but innumerable kinds of drinks peculiar to the Italian palate. It is possible that the café-pastry-shops of Italy are even better remembered by name than those of France. If the traveler carries away from the French Riviera the memory of Rumplemeyer, Vogaud and Philippe, she will certainly have somewhere in her baggage those of Nazzari, Ronzi, Doni and, above all, Florian, the key to who's establishment on the Piazza of San Marco was thrown into the Grand Canal some hundred odd years ago. With one's pasti dolci there are a half a dozen iced drinks to be had as their proper accompaniment — sorbet of partly frozen fruit juices; the popular granita, which may be described as a lemonade frappé; or any one of a line of liquori that the Italians lazily sip, accompanied by cinnamon powdered pastries, at eight or nine in the morning, even at noon, which latter habit makes one wonder, if a pastry repast does not often take the place of the Italian luncheon for many. The primary ingredients of Italian pastry are obviously almonds, which are made into a flour, also honey, pistache nuts, cinnamon and much cream, which, it must be said, much more resembles the cow-brand than that of France; and, of course, much chocolate, the strong, bitter, black, unsweetened chocolate of Italian composition, much less coffee flavoring being used than in France. Black chocolate replaces the brown moka; also the nougats of Italy are of burnt nuts and sugar, while those across the Alps are of blanched almonds and honey and are white. Thus the general impression to be had is that French pastry is much lighter in color than that of Italy. One picks out one's own cakes with plate and fork as in France. In the bigger establishments there are always tables, but "degustation" before the counter is quite usual and quite as chic. An Italian pasticceria gets its rating as to class by the number of its counters, or banci. Thus one of quattro banci approaches the very grand establishment, one which implies a large clientèle.  The always versatile drug store, in Italy, often adds another number to its repertoire, that of pastry and calls itself a Drogheria-Pasticceria, and of the latter it retails quite as much of an assortment as of the former. Even the avowed cafe caters to the ruling passion by blazoning on its front the additional word pasticceria. Even in the smallest towns the pastry standard is high, and the cup of coffee or chocolate that one gets with it is delicious. Traveling about Italy one should do as the Italians do and take his, or her, little breakfast at the café pasticceria, rather than in more conventional fashion at the hotel or restaurant, for the little unsweetened pastry breads of Italy are crisp and toothsome delights. Vendors of pastry pursue one through the streets of most Italian cities and towns, along with the hawkers of souvenirs, plaster casts and coral necklaces and violets, especially in Naples. Their vociferation rings all day on the merits of their rather dubious looking wares, spread out on a wooden circular tray, carried on the head or hanging by a leather strap from the neck. Made of indifferent brown flour, sugar of the third degree, eggs of a respectable age and with fillings of slices of roasted apples or quinces, baked in ashes instead of in an oven, they are offered all corners, chiefly finding buyers among the street workers and hawkers. But through every strata of affluence there extends the craze for pastry lumped into the one word dolci. The pastry cook of Naples is particularly savant in the art of pie-crust. Its favorite variety is the ancestor of that known in France as "Napoleon" or "mille feuille" i. e., "a thousand leaves"; the pate feuillettée, a classic Italian pasta, for which honor is claimed by its having been mentioned by Dante; elastic tradition even carries it back to the days of Horace. This pastry of a thousand leaves is made of uncountable layers of a flaky crust rolled to the thinness of a sheet of tissue and superimposed one on another until the required thickness is arrived at, when it is cut off into thin oblongs and powdered over with sugar. There are two varieties, the "curled" large leaves, flat, that crack like tiny shells under the teeth; and the "soft" and high as three fingers and coated with a varnish of thick custard cream between the leaves. The price of either will approximate three soldi, say three cents, before the war unbalanced Italian exchange. Other of the Neapolitan dolci are the hard-baked rings of sweet-bread powdered with sugar and aniseed, and the special pastries eaten to celebrate the great religious holidays throughout the year. Italy has a veritable pastry calendar and by following its rotations may be followed with precision the gastronomic pastry round. One of the most remarkable of these is known as the "High Tower", crisp and sparkling with particles of colored rock candy. It is always the adornment of festive tables on the eleventh of November, the feast of Saint Martin, and must always be divided with friends in honor of the charitable saint who divided his cloak with a fellow soldier while defending a besieged city.  THE PASTICCERIA-DROGHERIA OF A SMALL ITALIAN TOWN The north Italian city of Cremona, of sweet-toned violin fame, has another sweet specialty in a pastry which is eaten throughout Italy during the holiday season. The pasticceria displays it behind its plate-glass windows, also big almond tartes called royal mandorle torrone, made of a paste of sweet soft-shelled almonds, candied lemons and a liberal and varied assortment of spices mixed together with honey in a piecrust shell, and when decorated with tinsel, gilt balls and artificial flowers are, indeed, a gay ornament for the centerpiece of a ceremonial dinner table. Further, if one is to be in close touch with the Mardi Gras spirit, there are the sweet biscuits of Mid-Lent, while at Easter the pasticceria overflows with crowds who come to nibble with their syrups or chocolate the pastries of Pasqua, in whose composition honey and almonds play the rôle of pie-crust. Nuts are liberally sprinkled in and over Italian pastries, besides being used as a flour in their composition. The sweet kernel of the pine cone is much in vogue, both in Italy and southern France. One finds on both the French and Italian Rivieras this famous noix de pin in little crescent-shaped cakes, the kernels stuck like tiny ivory pins around their circumference, and with a taste that is most agreeable. Meringue is another favorite of both these Latin pastry-loving nations. This egg-shell-like pastry contains cream and it is known as à la Chantilly; filled with ice it is à la glace, and, in any case, it should always be eaten with a spoon. There is much fork-and-spoon etiquette involved in the supposedly simple business of eating pastry abroad, both à la Francaise and àlla Italiana and a study of it in connection therewith will be found worth while. Comparisons are worse than odious; they are as in-apropos and impolite as to say that a blond is more beautiful than a brunette. French pastry is of the blond type, while that of Italy is decidedly brunette. Take your choice. One distinction may be permitted —the characteristic of French pastry is delicacy; that of Italian is richness. |

HY

are they bracketed together?

HY

are they bracketed together?