| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2017

(Return

to Web

Text-ures)

|

|

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

VI PENCROFT'S HALLOOS — A NIGHT IN THE CHIMNEYS — HERBERT'S ARROWS — THE CAPTAIN'S PROJECT — AN UNEXPECTED EXPLANATION — WHAT HAS HAPPENED IN GRANITE HOUSE — HOW A NEW SERVANT ENTERS THE SERVICE OF THE COLONISTS. CYRUS HARDING stood still, without saying a word. His companions searched in the darkness on the wall, in case the wind should have moved the ladder, and on the ground, thinking that it might have fallen down. . . . But the ladder had quite disappeared. As to ascertaining if a squall had blown it on the landing-place, half way up, that was impossible in the dark. "If it is a joke," cried Pencroft, "it is a very stupid one; to come home and find no staircase to go up to your room by, for weary men, there is nothing to laugh at that I can see." Neb could do nothing but cry out "Oh! Oh! oh!" "I begin to think that very curious things happen in Lincoln Island!" said Pencroft. "Curious?" replied Gideon Spilett, "not at all, Pencroft, nothing can be more natural. Some one has come during our absence, taken possession of our dwelling and drawn up the ladder." "Some one," cried the sailor. "But who?" "Who but the hunter who fired the bullet?" replied the reporter. "Well, if there is any one up there," replied Pencroft, who began to lose patience, "I will give them a hail, and they must answer." And in a stentorian voice the sailor gave a prolonged "Halloo!" which was echoed again and again from the cliff and rocks. The settlers listened and they thought they heard a sort of chuckling laugh, of which they could not guess the origin. But no voice replied to Pencroft, who in vain repeated his vigorous shouts. There was something indeed in this to astonish the most apathetic of men, and the settlers were not men of that description. In their situation every incident had its importance, and, certainly, during the seven months which they had spent on the island, they had not before met with anything of so surprising a character. Be that as it may, forgetting their fatigue in the singularity of the event, they remained below Granite House, not knowing what to think, not knowing what to do, questioning each other without any hope of a satisfactory reply, every one starting some supposition each more unlikely than the last. Neb bewailed himself, much disappointed at not being able to get into his kitchen, for the provisions which they had had on their expedition were exhausted, and they had no means of renewing them. "My friends," at last said Cyrus Harding, "there is only one thing to be done at present, wait for day, and then act according to circumstances. But let us go to the Chimneys. There we shall be under shelter, and if we cannot eat, we can at least sleep." "But who is it that has played us this cool trick?" again asked Pencroft, unable to make up his mind to retire from the spot. Whoever it was, the only thing practicable was to do as the engineer proposed, to go to the Chimneys and there wait for day. In the meanwhile Top was ordered to mount guard below the windows of Granite House, and when Top received an order he obeyed it without any questioning. The brave dog therefore remained at the foot of the cliff while his master with his companions sought a refuge among the rocks. To say that the settlers, notwithstanding their fatigue, slept well on the sandy floor of the Chimneys would not be true. It was not only that they were extremely anxious to find out the cause of what had happened, whether it was the result of an accident which would be discovered at the return of day, or whether on the contrary it was the work of a human being; but they also had very uncomfortable beds. That could not be helped, however, for in some way or other at that moment their dwelling was occupied, and they could not possibly enter it. Now Granite House was more than their dwelling, it was their warehouse. There were all the stores belonging to the colony, weapons, instruments, tools, ammunition, provisions, etc. To think that all that might be pillaged and that the settlers would have all their work to do over again, fresh weapons and tools to make, was a serious matter. Their uneasiness led one or other of them also to' go out every few minutes to see if Top was keeping good watch. Cyrus Harding alone waited with his habitual patience, although his strong mind was exasperated at being confronted with such an inexplicable fact, and he was provoked at himself for allowing a feeling to which he could not give a name, to gain an influence over him. Gideon Spilett shared his feelings in this respect, and the two conversed together in whispers of the inexplicable circumstance which baffled even their intelligence and experience. "It is a joke," said Pencroft; "it is a trick some one has played us. Well, I don't like such jokes, and the joker had better look out for himself, if he falls into my hands, I can tell him." As soon as the first gleam of light appeared in the east, the colonists, suitably armed, repaired to the beach under Granite House. The rising sun now shone on the cliff and they could see the windows, the shutters of which were closed, through the curtains of foliage. All here was in order; but a cry escaped the colonists when they saw that the door, which they had closed on their departure, was now wide open. Some one had entered Granite House — there could be no more doubt about that. The upper ladder, which generally hung from the door to the landing, was in its place, but the lower ladder was drawn up and raised to the threshold. It was evident that the intruders had wished to guard themselves against a surprise. Pencroft hailed again. No reply. "The beggars," exclaimed the sailor. "There they are sleeping quietly as if they were in their own house. Hallo there, you pirates, brigands, robbers, sons of John Bull!" When Pencroft, being a Yankee, treated any one to the epithet of "son of John Bull," he considered he had reached the last limits of insult. The sun had now completely risen, and the whole facade of Granite House became illuminated by his rays; but in the interior as well as on the exterior all was quiet and calm. The settlers asked if Granite House was inhabited or not, and yet the position of the ladder was sufficient to show that it was; it was also certain that the inhabitants, whoever they might be, had not been able to escape. But how were they to be got at? Herbert then thought of fastening a cord to an arrow, and shooting the arrow so that it should pass between the first rounds of the ladder which hung from the threshold. By means of the cord they would then be able to draw down the ladder to the ground, and so re-establish the communication between the beach and Granite House. There was evidently nothing else to be done, and, with a little skill, this method might succeed. Very fortunately bows and arrows had been left at the Chimneys, where they also found a quantity of light hibiscus cord. Pencroft fastened this to a well-feathered arrow. Then Herbert fixing it to his bow, took a careful aim for the lower part of the ladder. Cyrus Harding, Gideon Spilett, Pencroft, and Neb drew back, so as to see if anything appeared at the windows. The reporter lifted his gun to his shoulder and covered the door. The bow was bent, the arrow flew, taking the cord with it, and passed between the two last rounds.

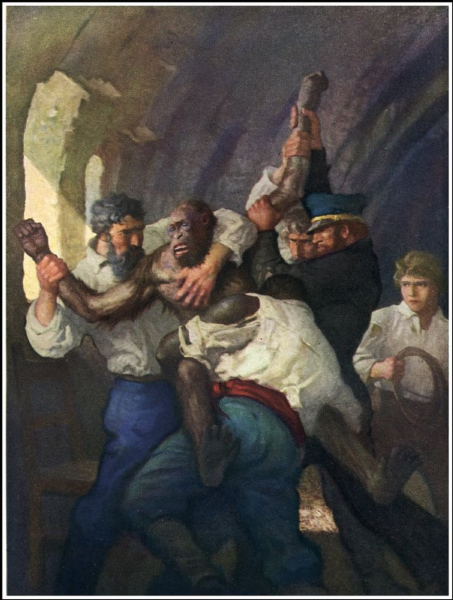

The capture of the orang The operation had succeeded. Herbert immediately seized the end of the cord, but, at that moment when he gave it a pull to bring down the ladder, an arm, thrust suddenly out between the wall and the door, grasped it and dragged it inside Granite House. "The rascals!" shouted the sailor. "If a ball can do anything for you, you shall not have long to wait for it." "But who was it?" asked Neb. "Who was it? Didn't you see?" "No." "It was a monkey, a sapago, an orang-outang, a baboon, a gorilla, a sagoin. Our dwelling has been invaded by monkeys, who climbed up the ladder during our absence." And, at this moment, as if to bear witness to the truth of the sailor's words, two or three quadrumana showed themselves at the windows, from which they had pushed back the shutters, and saluted the real proprietors of the place with a thousand hideous grimaces. "I knew that it was only a joke," cried Pencroft; "but one of the jokers shall pay the penalty for the rest." So saying, the sailor, raising his piece, took a rapid aim at one of the monkeys and fired. All disappeared, except one who fell mortally wounded on the beach. This monkey, which was of a large size, evidently belonged to the first order of the quadrumana. Whether this was a chimpanzee, an orang-outang, or a gorilla, he took rank among the anthropoid apes, who are so called from their resemblance to the human race. However, Herbert declared it to be an orang-outang. "What a magnificent beast!" cried Neb. "Magnificent, if you like," replied Pencroft; "but still I do not see how we are to get into our house." "Herbert is a good marksman," said the reporter, "and his bow is here. He can try again." "Why, these apes are so cunning," returned Pencroft; "they won't show themselves again at the windows and so we can't kill them; and when I think of the mischief they may do in the rooms and storehouse — " "Have patience,* replied Harding; "these creatures cannot keep us long at bay." "I shall not be sure of that till I see them down here," replied the sailor. "And now, captain, do you know how many dozens of these fellows are up there?' It was difficult to reply to Pencroft, and as for the young boy making another attempt, that was not easy; for the lower part of the ladder had been drawn again into the door, and when another pull was given, the line broke and the ladder remained firm. The case was really perplexing. Pencroft stormed. There was a comic side to the situation, but he did not think it funny at all. It was certain that the settlers would end by reinstating themselves in their domicile and driving out the intruders, but when and how? this is what they were not able to say. Two hours passed, during which the apes took care not to show themselves, but they were still there, and three or four times a nose or a paw was poked out at the door or windows, and was immediately saluted by a gun-shot. "Let us hide ourselves," at last said the engineer. "Perhaps the apes will think we have gone quite away and will show themselves again. Let Spilett and Herbert conceal themselves behind those rocks and fire on all that may appear." The engineer's orders were obeyed, and while the reporter and the lad, the best marksmen in the colony, posted themselves in a good position, but out of the monkey's sight, Neb, Pencroft, and Cyrus climbed the plateau and entered the forest in order to kill some game, for it was now time for breakfast and they had no provisions remaining. In half an hour the hunters returned with a few rock pigeons, which they roasted as well as they could. Not an ape had appeared. Gideon Spilett and Herbert went to take their share of the breakfast, leaving Top to watch under the windows. They then, having eaten, returned to their post. Two hours later, their situation was in no degree improved. The quadrumana gave no sign of existence, and it might have been supposed that they had disappeared; but what seemed more probable was that, terrified by the death of one of their companions, and frightened by the noise of the firearms, they had retreated to the back part of the house or probably even into the store-room. And when they thought of the valuables which this store-room contained, the patience so much recommended by the engineer, fast changed into great irritation, and there certainly was room for it. "Decidedly it is too bad," said the reporter; "and the worst of it is, there is no way of putting an end to it." "But we must drive these vagabonds out somehow," cried the sailor. "We could soon get the better of them, even if there are twenty of the rascals; but for that, we must meet them hand to hand. Come now, is there no way of getting at them?" "Let us try to enter Granite House by the old opening at the lake," replied the engineer. "Oh!" shouted the sailor, "and I never thought of that." This was in reality the only way by which to penetrate into Granite House so as to fight with and drive out the intruders. The opening was, it is true, closed up with a wall of cemented stones, which it would be necessary to sacrifice, but that could easily be rebuilt. Fortunately, Cyrus Harding had not as yet effected his project of hiding this opening by raising the waters of the lake, for the operation would then have taken some time. It was already past twelve o'clock, when the colonists, well armed and provided with picks and spades, left the Chimneys, passed beneath the windows of Granite House, after telling Top to remain at his post, and began to ascend the left bank of the Mercy, so as to reach Prospect Heights. But they had not made fifty steps in this direction, when they heard the dog barking furiously. And all rushed down the bank again. Arrived at the turning, they saw that the situation had changed. In fact, the apes, seized with a sudden panic, from some unknown cause, were trying to escape. Two or three ran and clambered from one window to another with the agility of acrobats. They were not even trying to replace the ladder, by which it would have been easy to descend; perhaps in their terror they had forgotten this way of escape. The colonists, now being able to take aim without difficulty, fired. Some, wounded or killed, fell back into the rooms, uttering piercing cries. The rest, throwing themselves out, were dashed to pieces in their fall, and in a few minutes, so far as they knew, there was not a living quadrumana in Granite House. At this moment the ladder was seen to slip over the threshold, then unroll and fall to the ground. "Hullo!" cried the sailor, "this is queer!" "Very strange!" murmured the engineer, leaping first up the ladder. "Take care, captain!" cried Pencroft, "perhaps there are still some of these rascals. . .” "We shall soon see," replied the engineer, without stopping however. All his companions followed him, and in a minute they had arrived at the threshold. They searched everywhere. There was no one in the rooms nor in the storehouse, which had been respected by the band of quadrumana. "Well now, and the ladder," cried the sailor; "who can the gentleman have been who sent us that down?" But at that moment a cry was heard, and a great orang, who had hidden himself in the passage, rushed into the room, pursued by Neb. "Ah, the robber!" cried Pencroft. And hatchet in hand, he was about to cleave the head of the animal, when Cyrus Harding seized his arm, saying, "Spare him, Pencroft." "Pardon this rascal?" "Yes! it was he who threw us the ladder!" And the engineer said this in such a peculiar voice that it was difficult to know whether he spoke seriously or not. Nevertheless, they threw themselves on the orang, who defended himself gallantly, but was soon overpowered and bound. "There!" said Pencroft. "And what shall we make of him, now we've got him?" "A servant!" replied Herbert. The lad was not joking in saying this, for he knew how this intelligent race could be turned to account. The settlers then approached the ape and gazed at it attentively. He belonged to the family of anthropoid apes, of which the facial angle is not much inferior to that of the Australians and Hottentots. It was an orang-outang, and as such, had neither the ferocity of the gorilla, nor the stupidity of the baboon. It is to this family of the anthropoid apes that so many characteristics belong which prove them to be possessed of an almost human intelligence. Employed in houses, they can wait at table, sweep rooms, brush clothes, clean boots, handle a knife, fork, and spoon properly, and even drink wine, . . . doing everything as well as the best servant that ever walked upon two legs. Buffon possessed one of these apes, who served him for a long time as a faithful and zealous servant. The one which had been seized in the hall of Granite House was a great fellow, six feet high, with an admirably proportioned frame, a broad chest, head of a moderate size, the facial angle reaching sixty-five degrees, round skull, projecting nose, skin covered with soft glossy hair, in short, a fine specimen of the anthropoids. His eyes, rather smaller than human eyes, sparkled with intelligence; his white teeth glittered under his mustache, and he wore a little curly brown beard. "A handsome fellow!" said Pencroft; "if we only knew his language, we could talk to him." "But, master," said Neb, "are you serious? Are we going to take him as a servant?" "Yes, Neb," replied the engineer, smiling. "But you must not be jealous." "And I hope he will make an excellent servant," added Herbert. "He appears young, and will be easy to educate, and we shall not be obliged to use force to subdue him, nor draw his teeth, as is some-• times done. He will soon grow fond of his masters if they are kind to him." "And they will be," replied Pencroft, who had forgotten all his rancor against "the jokers." Then, approaching the orang,- "Well, old boy!" he asked, "how are you?" The orang replied by a little grunt which did not show any anger. "You wish to join the colony?" again asked the sailor. "You are going to enter the service of Captain Cyrus Harding?" Another respondent grunt was uttered by the ape. "And you will be satisfied with no other wages than your food?" Third affirmative grunt. "This conversation is slightly monotonous," observed Gideon Spilett. "So much the better," replied Pencroft; "the best servants are those who talk the least. And then, no wages, do you hear my boy? We will give you no wages at first, but we will double them afterwards if we are pleased with you." Thus the colony was increased by a new member. As to his name the sailor begged that in memory of another ape which he had known, he might be called Jupiter, and Jup for short.

And

so, without more ceremony, Master Jup was installed in Granite House.  |