Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre

and the Basque Provinces

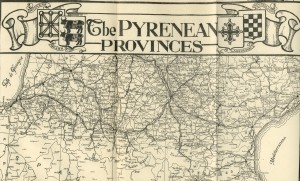

[Click on map for larger image]

CHAPTER

I

A

GENERAL SURVEY

THIS

book is no record of exploitation or discovery; it is simply a review

of many things seen and heard anent that marvellous and

comparatively little known region vaguely described

as "the Pyrenees," of which the old French provinces (and

before them the independent kingdoms, countships and

dukedoms) of Béarn, Navarre, Foix and Roussillon are the chief and

most familiar.

The

region has been known as a touring ground for long years, and

mountain climbers who have tired of the monotony of the Alps have

found much here to quicken their jaded appetites. Besides this, there

is a wealth of historic fact and a quaintness of men and manners

throughout all this wonderful country of infinite

variety, which has been little worked, as yet, by any but the

guide-book makers, who deal with only the dryest of details and with

little approach to completeness.

The

monuments of the region, the historic and ecclesiastical shrines, are

numerous enough to warrant a very extended review, but they have only

been hinted at once and again by travellers who have usually made the

round of the resorts like Biarritz, Pau, Luchon and Lourdes their

chief reason for coming here at all.

Delightful

as are these places, and a half a dozen others whose names are less

familiar, the little known townlets with their historic sites —

such as Mazères, with its Château de Henri Quatre, Navarreux,

Mauléon, Morlaas, Nay, and Bruges (peopled originally by Flamands)

— make up an itinerary quite as important as one

composed of the names of places writ large in the guide-books and in

black type on the railway-maps.

The

region of the Pyrenees is most accessible, granted it is

off the regular beaten travel track. The tide of Mediterranean travel

is breaking hard upon its shores to-day; but few who are washed

ashore by it go inland from Barcelona and Perpignan, and so on to the

old-time little kingdoms of the Pyrenees. Fewer still among those who

go to southern France, via Marseilles, ever think of turning westward

instead of eastward — the attraction of Monte Carlo and its

satellite resorts is too great. The same is true of those about to do

"the Spanish tour," which usually means Holy Week at

Seville, a day in the Prado and another at the Alhambra and Grenada,

Toledo of course, and back again north to Paris, or to take ship at

Gibraltar. En route they may have stopped at Biarritz, in Franc e, or

San Sebastian, in Spain, because it is the vogue just at present, but

that is all.

It

was thus that we had known "the Pyrenees." We knew Pau and

its ancestral château of Henri Quatre; had had a look at Biarritz;

had been to Lourdes, Luchon and Tarbes and even to Cauterets and

Bigorre, and to Foix, Carcassonne and Toulouse, but those were

reminiscences of days of railway travel. Since that time the

automobile has come to make travel in out-of-the-way places easy, and

instead of having to bargain for a sorry hack to take us through the

Gorges de Pierre Lys, or from Perpignan to Prats-de-Mollo

we found an even greater pleasure in finding our own way and setting

our own pace.

This

is the way to best know a country not one's own, and whether we were

contemplating the spot where Charlemagne and his

followers met defeat at the hands of the Mountaineers,

or stood where the Romans erected their great trophée, high

above Bellegarde, we were sure that we were always on the trail we

would follow, and were not being driven hither and thither by a

cocher who classed all strangers as "mere tourists,"

and pointed out a cavern with gigantic stalagmites or a profile rock

as being the "chief sights" of his neighbourhood, when near

by may have been a famous battle-ground or the château where was

born the gallant Gaston Phœbus. Really, tourists, using the word in

its overworked sense, are themselves responsible for much that is

banal in the way of sights; they won't follow out their own

predilections, but walk blindly in the trail of others whose tastes

may not be their own.

Travel

by road, by diligence or omnibus, is more frequent all through the

French departments bordering on the Pyrenees than in any

other part of France, save perhaps in Dauphiné and Savoie, and the

linking up of various loose ends of railway by such a means is one of

the delights of travel in these parts — if you don't happen to have

an automobile handy.

Beyond

a mere appreciation of mediæval architectural delights of châteaux,

manoirs, and gentilhommières of the region, this book

includes some comments on the manner of living in those far-away

times when chivalry flourished on this classically romantic ground.

It treats, too, somewhat of men and manners of to-day, for here in

this southwest corner of France much of modern life is but a

reminiscence of that which has gone before.

Many

of the great spas of to-day, such as the Bagnères de Bigorre, Salies

de Béarn, Cauterets, Eaux-Bonnes, or Amélie les Bains, have a

historic past, as well as a present vogue. They were known in some

cases to the Romans, and were often frequented by the royalties of

the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and therein is another link

which binds the present with the past.

One

feature of the region resulting from the alliance of the life of the

princes, counts and seigneurs of the romantic past, with that of the

monks and prelates of those times is the religious architecture.

Since

the overlord or seigneur of a small district was often an amply

endowed archbishop or bishop, or the lands round about

belonged by ancient right to some community of monkish

brethren, it is but natural that mention of some of their more

notable works and institutions should have found a place herein.

Where such inclusion is made, it is always with the consideration of

the part played in the stirring affairs of mediæval times by some

fat monk or courtly prelate, who was, if not a compeer, at least a

companion of the lay lords and seigneurs.

Not

all the fascinating figures of history have been princes and counts;

sometimes they were cardinal-archbishops, and when they were wealthy

and powerful seigneurs as well they became at once principal

characters on the stage. Often they have been as romantic and

chivalrous (and as intriguing and as greedy) as the most dashing hero

who ever wore cloak and doublet.

Still

another species of historical characters and monuments is

found plentifully besprinkled through the pages of the

chronicles of the Pyrenean kingdoms and provinces, and that is the

class which includes warriors and their fortresses.

A

castle may well be legitimately considered as a fortress, and a

château as a country house; the two are quite distinct one from the

other, though often their functions have been combined.

Throughout

the Pyrenees are many little walled towns, fortifications,

watch-towers and what not, architecturally as splendid, and as great,

as the most glorious domestic establishment of

Renaissance days. The cité of Carcassonne, more

especially, is one of these. Carcassonne's château is as

naught considered without the ramparts of the mediæval

cité, but together, what a splendid historical souvenir they form!

The most splendid, indeed, that still exists in Europe, or perhaps

that ever did exist.

Prats-de-Mollo

and its walls, its tower, and the defending Fort Bellegarde; Saint

Bertrand de Comminges and its walls; or even the quaintly picturesque

defences of Vauban at Bayonne, where one enters the city to-day

through various gateway breaches in the walls, are all as reminiscent

of the vivid life of the history-making past, as is Henri Quatre's

tortoise-shell cradle at Pau, or Gaston de Foix' ancestral château

at Mazères.

Mostly

it is the old order of things with which one comes into contact here,

but the blend of the new and old is sometimes astonishing. Luchon and

Pau and Tarbes and Lourdes, and many other places for that matter,

have over-progressed. This has been remarked before now; the writer

is not alone in his opinion.

The

equal of the charm of the Pyrenean country, its historic sites, its

quaint peoples, and its scenic splendours does not exist in all

France. It is a blend of French and Spanish manners and blood,

lending a colour-scheme to life that is most enjoyable to the seeker

after new delights.

Before

the Revolution, France was divided into fifty-two provinces, made up

wholly from the petty states of feudal times. Of the southern

provinces, seven in all, this book deals in part with Gascogne

(capital Auch), the Comté de Foix (capital Foix), Roussillon

(capital Perpignan), Haute-Languedoc (capital Toulouse), and

Bas-Languedoc (capital Montpellier). Of the southwest

provinces, a part of Guyenne (capital Bordeaux) is included, also

Navarre (capital Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port) and Béarn (capital Pau).

Besides

these general divisions, there were many minor petits pays

compressed within the greater, such as Armagnac, Comminges, the

Condanois, the Pays-Entre-Deux-Mers, the Landes, etc. These, too,

naturally come within the scope of this book.

Finally,

in the new order of things, the ancient provinces lost their

nomenclature after the Revolution, and the Département of the Landes

(and three others) was carved out of Guyenne; the Département of the

Basses-Pyrénées absorbed Navarre, Béarn and the Basque provinces;

Bigorre became the Hautes-Pyrénées; Foix became Ariège; Roussillon

became the Pyréneés-Orientales, and Haute-Languedoc

and Bas-Languedoc gave Hérault, Gard, Haute-Garonne and the Aude.

For the most part all come within the scope of these pages, and

together these modern départements form an unbreakable historical

and topographical frontier link from the Atlantic to the

Mediterranean.

This

bird's-eye view of the Pyrenean provinces, then, is a sort of

picturesque, informal report of things seen and facts

garnered through more or less familiarity with the

region, its history, its institutions and its people.

Châteaux and other historical monuments, agriculture and landscape,

market-places and peasant life, all find a place here, inasmuch as

all relate to one another, and all blend into that very nearly

perfect whole which makes France so delightful to the traveller.

Everywhere

in this delightful region, whether on the mountain side or in the

plains, the very atmosphere is charged with an extreme of

life and colour, and both the physiognomy of landscape and the

physiognomy of humanity is unfailing in its appeal to

one's interest.

Here

there are no guide-book phrases in the speech of the people, no

struggling lines of "conducted" tourists with a polyglot

conductor, and no futile labelling of doubtful historic

monuments; there are enough of undoubted authenticity

without this.

Thoroughly

tired and wearied of the progress and super-civilization

of the cities and towns of the well-worn roads, it becomes a real

pleasure to seek out the by-paths of the old French provinces, and

their historic and romantic associations, in their very crudities and

fragments every whit as interesting as the better known

stamping-grounds of the conventional tourist.

The

folk of the Pyrenees, in their faces and figures, in their speech and

customs, are as varied as their histories. They are a bright, gay,

careless folk, with ever a care and a kind word for the stranger,

whether they are Catalan, Basque or Béarnais.

Since

the economic aspects of a country have somewhat to do with its

history it is important to recognize that throughout the

Pyrenees the grazing and wine-growing industries

predominate among agricultural pursuits.

There

is a very considerable raising of sheep and of horses and mules, and

somewhat of beef, and there is some growing of grain, but in the main

— outside of the sheep-grazing of the higher valleys — it is the

wine-growing industry that gives the distinctive note , of activity

and prosperity to the lower slopes and plains.

For

the above mentioned reason it is perhaps well to recount here just

what the wine industry and the wine-drinking of France amounts to.

One

may have a preference for Burgundy or Bordeaux, Champagne or Saumur,

or even plain, plebeian beer, but it is a pity that the great mass of

wine-drinkers, outside of Continental Europe, do not make

their distinctions with more knowledge of wines when they say this or

that is the best one, instead of making their estimate by the

prices on the wine-card. Anglo-Saxons (English and Americans) are for

the most part not connoisseurs in wine, because they

don't know the fundamental facts about wine-growing.

For

red wines the Bordeaux — less full-bodied and heavy — are very

near rivals of the best Burgundies, and have more bouquet and more

flavour. The Medocs are the best among Bordeaux wines.

Château-Lafitte and Château-Latour are very rare in

commerce and very high in price when found. They come from the

commune of Pauillac. Château Margaux, St. Estèphe and

St. Julien follow in the order named and are the leaders among the

red wines of Bordeaux — when you get the real thing, which you

don't at bargain store prices.

The

white wines of Bordeaux, the Graves, come from a rocky soil; the

Sauternes, with the vintage of Château d'Yquem, lead the list, with

Barsac, Entre-Deux-Mers and St. Emilion following. There are

innumerable second-class Bordeaux wines, but they need not be

enumerated, for if one wants a name merely there are plenty of wine

merchants who will sell him any of the foregoing beautifully bottled

and labelled as the "real thing."

Down

towards the Pyrenees the wines change notably in colour, price and

quality, and they are good wines too. Those of Bergerac and Quercy

are rich, red wines sold mostly in the markets of Cahors; and the

wines of Toulouse, grown on the sunny hill-slopes between Toulouse

and the frontier, are thick, alcoholic wines frequently blended with

real Bordeaux — to give body, not flavour.

The

wines of Armagnac are mostly turned into eau de vie, and just

as good eau de vie as that of Cognac, though without its

flavour, and without its advertising, which is the chief reason why

the two or three principal brands of cognac are called for at the

wine-dealers.

At

Chalosse, in the Landes, between Bayonne and Bordeaux, are also grown

wines made mostly into eau de vie.

Béarn

produces a light coloured wine, a specialty of the country, and an

acquired taste like olives and Gorgonzola cheese. From Béarn, also,

comes the famous cru de Jurançon, celebrated since the days

of Henri Quatre, a simple, full-bodied, delicious-tasting, red wine.

Thirteen

départements of modern France comprise largely the wine-growing

region of the basin of the Garonne, included in the territory covered

by this book. This region gives a wine crop of thirteen and a half

millions of hectolitres a year. In thirty years the

production has augmented by sixty per cent., and still dealers very

often sell a fabricated imitation of the genuine thing.

Wine drinking is increasing as well as alcoholism, regardless of what

the doctors try to prove.

The

wines of the Midi of France in general are famous, and have been for

generations, to bons vivants. The soil, the climate and pretty

much everything else is favourable to the vine, from the Spanish

frontier in the Pyrenees to that of Italy in the Alpes-Maritimes. The

wines of the Midi are of three sorts, each quite distinct from the

others; the ordinary table wines, the cordials, and the wines for

distilling, or for blending. Within the topographical

confines of this book one distinguishes all three of

these groups, those of Roussillon, those of Languedoc, and those of

Armagnac.

The

rocky soil of Roussillon, alone, for example

(neighbouring Collioure, Banyuls and Rivesaltes), gives each of the

three, and the heavy wines of the same region, for blending (most

frequently with Bordeaux), are greatly in demand among expert

wine-factors all over France. In the Département de l'Aude, the

wines of Lézignan and Ginestas are attached to this last group. The

traffic in these wines is concentrated at Carcassonne and Narbonne.

At Limoux there is a specialty known as Blanquette de

Limoux — a wine greatly esteemed, and almost as good an imitation

of champagne as is that of Saumur.

In

Languedoc, in the Département of Hérault, and Gard, twelve millions

of hectolitres are produced yearly of a heavy-bodied red wine, also

largely used for fortifying other wines and used, naturally, in the

neighbourhood, pure or mixed with water. This thinning out with water

is almost necessary; the drinker who formerly got outside of three

bottles of port before crawling under the table, would go to pieces

long before he had consumed the same quantity of local wine unmixed

with water at a Montpellier or Béziers table d'hôte.

At

Cette, at Frontignan, and at Lunel are fabricated many "foreign"

wines, including the Malagas, the Madères and the Xeres of commerce.

Above all the Muscat de Frontignan is revered among its

competitors, and it's not a "foreign" wine either, but the

juice of dried grapes or raisins, — grape juice if you like, — a

sweet, mild dessert wine, very, very popular with the ladies.

There

is a considerable crop of table raisins in the Midi, particularly at

Montauban and in maritime Provence which, if not rivalling those of

Malaga in looks, have certainly a more delicate flavour.

Along

with the wines of the Midi may well be coupled the olives. For oil

those of the Bouches-du-Rhône are the best. They bring the highest

prices in the foreign market, but along the easterly slopes of the

Pyrenees, in Roussillon, in the Aude, and in Hérault and Gard they

run a close second. The olives of France are not the fat, plump,

"queen" olives, sold usually in little glass jars, but a

much smaller, greener, less meaty variety, but richer in oil and

nutriment.

The

olive trees grow in long ranks and files, amid the vines or even

cereals, very much trimmed (in goblet shape, so that the ripening sun

may reach the inner branches) and are of small size. Their pale

green, shimmering foliage holds the year round, but demands a warm

sunny climate. The olive trees of the Midi of France — as far west

as the Comté de Foix in the Pyrenees, and as far north as Montelimar

on the Rhône — are quite the most frequently noted characteristic

of the landscape. The olive will not grow, however, above an altitude

of four hundred metres.

The

foregoing pages outline in brief the chief characteristics of the

present day aspect of the old Pyrenean French provinces of which

Béarn and Basse-Navarre, with the Comté de Foix were the heart and

soul.

The

topographical aspect of the Pyrenees, their history, and as full a

description of their inhabitants as need be given will be found in a

section dedicated thereto.

For

the rest, the romantic stories of kings and counts, and of lords and

ladies, and their feudal fortresses and Renaissance châteaux, with a

mention of such structures of interest as naturally come within

nearby vision will be found duly recorded further on.

|