| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

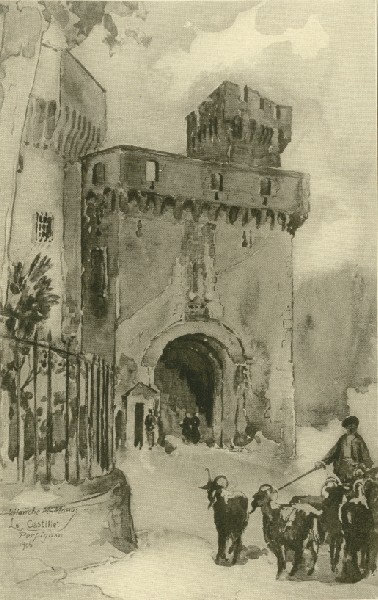

| CHAPTER VI

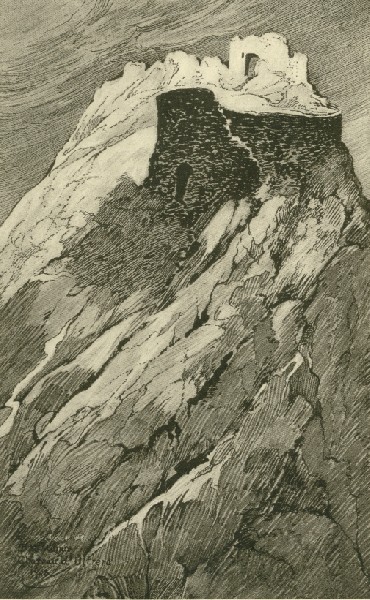

FROM PERPIGNAN TO THE SPANISH FRONTIER  ARMS OF PERPIGNAN ONCE Perpignan was a fortified town of the first class, but now, save for its old Citadelle and the Castillet, its warlike aspect has disappeared. One of Guy de Maupassant's heroes, having been asked his impressions of Algiers, replied, "Alger est une ville blanche!" If it had been Perpignan of which he was speaking, he would have said: "Perpignan est une ville rouge!" for red is the dominant colour note of the entire city, from the red brick Castillet to the sidewalks in front of the cafés. Colour, however, is not the only thing that astonishes one at Perpignan; the tramontane, that cruel northwest wind, as cruel almost as the "mistral" of Provence, blows at times so fiercely that one wonders that one brick upon another stands in place on the grand old Castillet tower. The brick fortifications of Perpignan are, or were, wonderful constructions, following, in form and system, the ancient Roman manner. It was a sacrilege to strip from the lovely city of Perpignan its triple ramparts and Citadelle, leaving only the bare walls of the Castillet, the sole remainder of its strength of old.  PORTE NOTRE DAME AND THE CASTILLET, PERPIGNAN Perpignan's walls have disappeared, but still one realizes full well what an important strategic point it is, guarding, as it does, the eastern gateway into Spain. All the cities of the Midi possess some characteristic by which they are best known. Toulouse has its Capitole, Nîmes its Arena, Arles its Alyscamps, Pau its Château, and Perpignan its Castillet. Built entirely of rosy-red brick, its battlemented walls rise beside the Quai de la Basse to-day as proudly as they ever did, though shorn of their supporting ramparts, save the Porte Notre Dame adjoining. That fortunately has been spared. Above this Porte Notre Dame is a figure of the Madonna, which, as well as the gate, dates from the period when the kings of Aragon retook possession of the ephemeral Royaume de Majorque, of which Perpignan was the capital, — a glory, by the way, which endured less than seventy years, but which has left a noticeable trace in all things relating to the history of the region. In the tenth century Perpignan was known only as "Villa Perpiniani," indeed it so remained until it was conquered by Louis XIII, when it became definitely French. Bloody war, celebrated sieges, ravages by the pest, an earthquake or two, and incendiaries without number could not raze the city which in time became one of the great frontier strongholds of France. The Place de la Loge, the great café centre of Perpignan, is unique among the smaller cities of France. Here is animation at all hours of the day — and night, a perpetual going and coming of all the world, a veritable Rialto or a Rue de la Paix. It is the business centre of the city, and also the centre of its pleasures, a veritable forum. Cafés are all about; even the grand old Loge de Mer, a delicious construction of the fourteenth century, is a café. What a charming structure this Loge is! Its fourteenth-century constructive elements have been further beautified with late flowering Gothic of a century and a half later, and its great bronze lamps suggest a symbolism which stands for eternity, or at any rate bespeaks the solidity of Perpignan for all time. Beside the Loge is the Hôtel de Ville, with its round-arched doorways and windows, iron-barred in real medieval fashion, with dainty colonnettes between. Next is the ancient Palais de Justice, adjoining the Hôtel de Ville. It has a battery of mullioned twin windows of narrow aperture, and is in perfect keeping with the medieval trinity of which it is a part. The cathedral of St. Jean is another of Perpignan's historical monuments, but it is far from lovely at first glance, an atrocious façade having been added by some "restorer" in recent times with more suitable ideas for building fortresses than churches. The tower of the cathedral is modern and, taken as a whole, is undeniably effective with its iron cage and bell-rack. The original tower fell two centuries ago during an extra violent blow of the tramontane. Passing centuries have changed Perpignan but little, and aside from the boulevards and malls the streets are narrow and tortuous and almost devoid of sidewalks. There are innumerable little bijou houses of Gothic or Renaissance times, and in one narrow street, called quaintly Main de Fer, one sees a real, unspoiled bit of the sixteenth century. One curious house, now occupied by the Cercle de l'Union, dates from 1508, and was erected for one Sancho or Xanxo. Its interior, so far as its entrance hall and stairway are concerned, remains as it was when first built. The Rue Père Pigne has a legend connected with it which is worth recounting. The Père Pigne, or Pigna, as his name was in Catalan-Spanish days, was a cattle-herder in the upper valley of the Tet, beside the village of Llagone. Weary of his lonely life he whispered to the rocks and rills his desire for a less rude calling elsewhere, and the river took him up in its arms and washed him incontinently down on to the lowland plain of Roussillon, and, by some occult means or other, suggested to the old man that his mission in life was to found there a fertile, prosperous city. Thus Perpignan came to be founded. There may be doubts as to the authenticity of the story, but there was enough of reality attached to it to have led the city fathers to name a street after the hero of the adventure. Since the demolishment of its walls Perpignan has lost much of its mediæval character, but nothing can take away the life and gaiety of its streets and boulevards, its shops, its hotels and cafés. Perpignan comes very near being the liveliest little capital of old France existing under the modern republic of to-day. The population is cosmopolitan, like that of Marseilles, and every aspect of it is picturesque. The vegetable sellers, the fruit merchants, the water and ice purveyors, all dark-eyed Catalan girls, are delightful in face, figure and carriage. Their baggy white coiffes set off their dark complexions and jet black hair. The men of this race are more serious when they are at business (they are gay enough at other times) and you may see twenty red onion or garlic dealers and never see a smile, whereas an orange seller, a woman or girl, always has her mouth open in a laugh and her headdress is always bobbing about; nothing about her is passive and life to her is a dream, though it is serious business to the men. The taste of the Catalans of Perpignan for bright colouring in their dress is akin to that of their brothers and sisters in Spain. The fact that both slopes of the Eastern Pyrenees were under the same domination up to the reign of Louis XIII may account for this. The Citadelle of Perpignan is closed to the general tourist. None may enter without permission from the military authorities, and that, for a stranger, is difficult to obtain. The great gateway to the Citadelle is a marvel of originality with its four archaic caryatides. Within is the site of the ancient palace of the kings of Majorca, but the primitive fragments have been rebuilt into the later works of Louis XI, Charles V and Vauban until to-day it is but a species of fortress, and not at all like a great domestic establishment such as one usually recognizes by the name of palace. The Église de la Real, beside the Citadelle, was built in the fourteenth century and is celebrated for the council held here in 1408 by the Anti-Pope, Pierre de Luna. There are some bibliographical gems in Perpignan's Bibliothèque which would make a new world collector envious. There are numerous rare incunabulæ and precious manuscripts, the most notable being the "Missel de l'Abbaye d'Arles en Vallespir" (XIIth century) and the "Missel de la Confrere," illustrated with miniatures (XVth century), worthy, each of them, to be ranked with King René's "Book of Hours" at Aix so far as mere beauty goes. The habituated French traveller connects rilettes with Tours, the Cannebière with Marseilles, Les Lices with Arles, and, with Perpignan, the platanes — great plane-trees, planted in a double line and forming one of the most remarkable promenades, just beyond the Castillet, that one has ever seen. It is a Prado, a Corso, and a Rambla all in one. The Carnival de Perpignan is as brilliant a fête as one may see in any Spanish or Italian city, where such celebrations are classic, and this Allée des Platanes is then at its gayest. Another of the specialties of Perpignan is the micocoulier, or "bois de Perpignan," something better suited for making whip handles than any other wood known. Each French city has its special industry; it may elsewhere be bérets, sabots, truffles, pork-pies or sausages, but here it is whips. Perpignan has given two great men to the world, Jean Blanca and Hyacinthe Rigaud. Jean Blanca, Bourgeois de Perpignan, was first consul of the city when Louis XI besieged it in 1475. His son had been captured by the besiegers and word was sent that he would be put to death if the gates were not opened forthwith. The courageous consul replied simply that the ties of blood and paternal love are not great enough to make one a traitor to his God, his king and his native land. His son was, in consequence, massacred beneath his very eyes. Hyacinthe Rigaud was a celebrated painter, born at Perpignan in the eighteenth century. His talents were so great that he was known as the Van Dyck français. Canet is a sort of seaside overflow of Perpignan, a dozen kilometres away on the shores of the Mediterranean. On the way one passes the scant, clumsy remains of the old twelfth-century Château Roussillon, now remodelled into a little ill-assorted cluster of houses, a chapel and a storehouse. The circular tower, really a svelt and admirable pile, is all that remains of the château of other days, the last vestige of the dignity that once was Ruscino's, the ancient capital of the Comté de Roussillon. At Canet itself there are imposing ruins, sitting hard by the sea, of centuries of regal splendour, though now they rank only as an attraction of the humble little village of Roussillon. The belfry of Canet's humble church looks like a little brother of that of "Perpignan-le-Rouge" and points plainly to the fact that styles in architecture are as distinctly local as are fashions in footwear.  CHÂTEAU ROUSSILLON Canet to-day is a watering place for the people of Perpignan, but in the past it was venerated by the holy hermits and monks of Roussillon for much the same attractions that it to-day possesses. Saint Galdric, patron of the Abbey of Saint Martin du Canigou, and, later, Saints Abdon and Sennen were frequenters of the spot. Rivesaltes, practically a suburb of Perpignan, a dozen kilometres north, is approached by as awful a road as one will find in France. The town will not suggest much or appeal greatly to the passing traveller, unless indeed he stops there for a little refreshment and has a glass of muscat, that sweet, sticky liquor which might well be called simply raisin juice. It is a "specialité du pays," and really should be tasted, though it may be had anywhere in the neighbourhood. It is a wine celebrated throughout France. At Salces, on the Route Nationale, just beyond Narbonne and Rivesaltes, is an old fortification built by Charles V on one of his ambitious pilgrimages across France. A great square of masonry, with a donjon tower in the middle and with walls of great thickness, it looks formidable enough, but modern Krupp or Creusot cannon would doubtless make short work of it. A dozen kilometres to the south of Perpignan is Elne, an ancient cathedral town. From afar one admires the sky line of the town and a nearer acquaintance but increases one's pleasure and edification. The Phoenicians, or the Iberians, founded the city, perhaps, five hundred years before the beginning of the Christian era, and Hannibal in his passage of the Pyrenees rested here. Another five hundred years and it had a Roman emperor for its guardian, and Constantine, who would have made it great and wealthy, surrounded it with ramparts and built a donjon castle, of which unfortunately not a vestige remains. Ages came and went, and the city dwindled in size, and the church grew poor with it, until at last, in 1601, Pope Clement VIII (a French Pope, by the way) authorized its bishop to move to Perpignan, where indeed the see has been established ever since. Of the past feudal greatness of Elne only a fragmentary rampart and the fortified Portes de Collioure and Perpignan remain. The rest must be taken on faith. Nevertheless, Elne is a place to be omitted from no man's itinerary in these parts. The great wealth and beauty of Elne's cathedral cannot be recounted here. They would require a monograph to themselves. Little by little much has been taken from it, however, until only the glorious fabric remains. To cite an example, its great High Altar, made of beaten silver and gold, was, under the will of the canons of the church themselves, in the time of Louis XV, sent to the mint at Perpignan and coined up into good current écus for the benefit of some one, history does not state whom. From the beautiful cloister, in the main a tenth-century work, and the largest and most beautiful in the Pyrenees, one steps out on a little perron when another ravishing Mediterranean panorama unfolds itself. There are others as fine; that from the platform of the château at Carcassonne; from the terrace at Pau; or from the citadel-fortress church at Béziers. This at Elne, however, is the equal of any. Below are the plains of Roussillon and Vallespir, red and green and gold like a tapis d'Orient, with the Albéres mountains for a background, while away in the distance, in a soft glimmering haze of a blue horizon, is the Mediterranean. It is all truly beautiful. In the direction of the Spanish frontier Argelès-sur-Mer comes next. It has historic value and its inhabitants number three thousand, though few recognize this, or have even heard its name. As a matter of fact, it might have become one of the great maritime cities of the eastern slope of the Pyrenees except that fickle fate ruled otherwise. The name of Argelès-sur-Mer figured first in a document of Lothaire, King of France, in 981; and, three centuries later, it was the meeting-place between the kings of Majorca and Aragon and the princes of Roussillon, when, at the instigation of Philippe le Bel, an expiring treaty was to be renewed. The city at that time belonged to the Royaume de Majorque, and Pierre IV of Aragon, in the Château d'Amauros, defended it through a mighty siege. Five hundred metres above the sea, and to be seen to-day, was also the Tour des Pujols, another fortification of the watch-tower or block-house variety, frequently seen throughout the Pyrenees. At the taking of Roussillon by Louis XI, Argelès-sur-Mer was in turn in possession of the King of Aragon and the King of France. Under Louis XIII the city surrendered with no resistance to the Maréchal de la Meilleraye; and later fell again to the Spaniards, becoming truly French in 1646. It was a Ville Royale with a right of vote in the Catalonian parliament, and enjoyed great privileges up to the Revolution, a fact which is plainly demonstrated by the archives of the city preserved at the local Mairie. In 1793 the Spanish flag again flew from its walls; but the brave Dugommier, the real saviour of this part of the Midi of France in revolutionary times, regained the city for the French for all time. Five kilometres south of Argelès-sur-Mer is Collioure, the ancient Port Ill berries, the seaport of Elne. It is one of the most curiously interesting of all the coast towns of Roussillon. Here one sees the best of the Catalan types of Roussillon, gentle maidens, coiffe on head, carrying water jugs with all the grace that nature gave them, and rough, hardy, red capped sailors as salty in their looks and talk as the sea itself. Collioure is not a grande ville. Even no it is a mere fishing port, and no one thinks of doing more than passing through its gates and out again. Nevertheless its historic interest endures. From the fact that Roman coins and pottery have been found here, its bygone position has been established as one of prominence. In the seventh century it was in the hands of the Visigoths and three centuries later Lothaire, King of France, gave permission to Winfred, Comte de Roussillon et temporizes, to develop and exploit the ancient settlement anew.  COLLIOURE Here, in 1280, Guillaume de Puig d'Or Phila founded a Dominican convent; and it is the Église de Collioure of to-day, sitting snugly by the entrance to the little port, that formed the church of the old conventual's establishment. In 1415 the Anti-Pope Benoit XIII, Pierre de Luna, took ship here, frightened from France by the menaces of Sigismond. Louis XI, when he sought to reduce Roussillon, would have treated Collioure hardly, but so earnest and skilful was its defence that it escaped the indignities thrust upon Elne and Perpignan. The kings of Spain for a time dominated the city, and during their rule the fortress known to-day as the Fort St. Elne was constructed. One of the red-letter incidents of Collioure was the shipwreck off its harbour of the Infanta of Spain, as she was en route by sea from Barcelona to Naples in 1584. A galley slave carried the noble lady on his shoulders as he swam to shore. News of the adventure came to the Bishop of Elne who was also plain Jean Terse, a Catalan and governor of the province; and he caused the unfortunate lady to be brought to the episcopal palace for further care. In return the princess used her influence at court and had the prelate made Archbishop of Tarragona, viceroy of Catalonia, and counsellor to the king of Spain. Of the forçat who really saved the lady, the chroniclers are blank. One may hope that he obtained some recompense, or at least liberty. There are numerous fine old Gothic and Renaissance houses here, with carved statues in niches, hanging lamps, great bronze knockers, and iron hinges, interesting enough to incite the envy of a curio-collector. Collioure has a great fête on the sixteenth of August of each year, the Fête de Saint Vincent. There is much procession going and coming from the sea in ships and gaily decorated boats, and after all fireworks on the water. The religious significance of it all is lost in the general rejoicing; but it's a most impressive sight nevertheless. Collioure is also famous for its fishing. The sardines and anchovies taken offshore from Collioure are famous all over France and Russia where gastronomy is an art. Two classic excursions are to be made from Collioure; one is to the hermitage of Notre Dame de Consolation, and the other to the Abbey of Valbonne. The first is simply a ruined hermitage seated on a little verdure-clad plateau high above the vineyards and olive orchards of the plain; but it is remarkably attractive, and it takes no great wealth of imagination to people the courtyard with the holy men of other days. Now its ruined, gray walls are set off with lichens, vines and rose-trees; and it is as quiet and peaceful a retreat from the world and its nerve-racking conventions as may be found. The Abbey of Valbonne is practically the counterpart of Notre Dame de Consolation so far as unworldliness goes. It was founded in 1242, but left practically deserted from the fifteenth century, after the invasion of Roussillon by Louis XL The Tour Massane, a great guardian watch-tower, dominates the ruins and marks the spot where Yolande, a queen of Aragon, lies buried.  CHÂTEAU D'ULTRERA Inland from Collioure, perhaps five kilometres in a bee line, but a dozen or more by a sinuous mountain path, high up almost on the crest of the Albères, is the château fort of Ultrera. Its name alone, without further description, indicates its picturesqueness, probably derived from the castrum vulturarium, or nest of vultures of Roman times. What the history of this stronghold may have been in later mediæval times no one knows; but it was a Roman outpost in the year 1073 and later a Visigoth stronghold. It was a fortress guarding the route to and from Spain via Narbonne, Salies, Ruscino, Elne, Saint André, Pave and so on to the Col de la Carbossière. Now this road is only a mule track and all the considerable traffic between the two countries passes via the Col de Perthus to the westward. The peak upon which sits Ultrera culminates at a height of five hundred and seventeen metres, and rises abruptly from the seashore plain in most spectacular fashion. The ruins are but ruins to be sure, but the grim suggestion of what they once stood for is very evident. En route from Perpignan or Collioure one passes the Ermitage de Notre Dame de Château, formerly a place of pious pilgrimage, and where travellers may still find refreshment. Banyuls-sur-Mer is the last French station on the railway leading into Spain. At Banyuls even a keen observer of men and things would find it hard, if he had been plumped down here in the middle of the night, to tell, on awaking in the morning, whether he was in Spain, Italy or Africa. The country round about is a blend of all three; with, perhaps, a little of Greece. It possesses a delicious climate and a flora almost as sub-tropical and as varied as that of Madeira. No shadow hangs over Banyuls-sur-Mer. The sea scintillates at its very doors; and, opposite, lie the gracious plains and valleys which reach to the crowning crests of the Pyrenees in the southwest. It is an ancient bourg, and its history recurs again and again in that of Roussillon. Turn by turn one reads in the pages of its chroniclers the names of the Comtes d'Empories-Roussillon, and the Rois de Majorque et d'Aragon. Lothaire and the then reigning Comte d'Empories came to an arrangement in the tenth century whereby the hill above the town was to be fortified by the building of a château or mas. This was done; but the seaport never prospered greatly until the union of France and Roussillon, when its people, whose chief source of prosperity had been a contraband trade, took their proper place in the affairs of the day. The National Convention subsequently formulated a decree that the "Banyulais ayant bien merité de la patrie," and ordered that an obelisk be erected commemorative of the capitulation of the Spaniards. For long years this none too lovely monument was unbuilt, — "Banyuls est si loin de Paris," said the habitant in explanation — but to-day it stands in all its ugliness on the quay by the waterside. |