| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

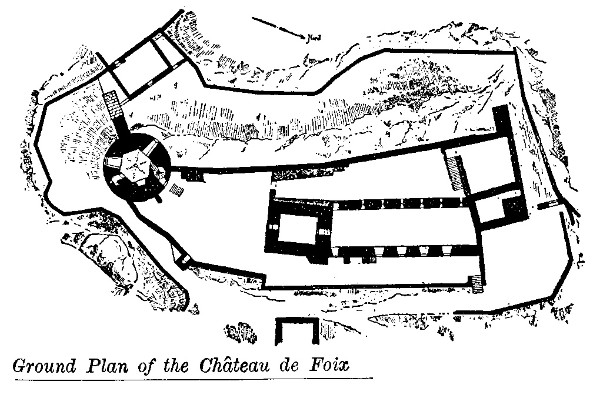

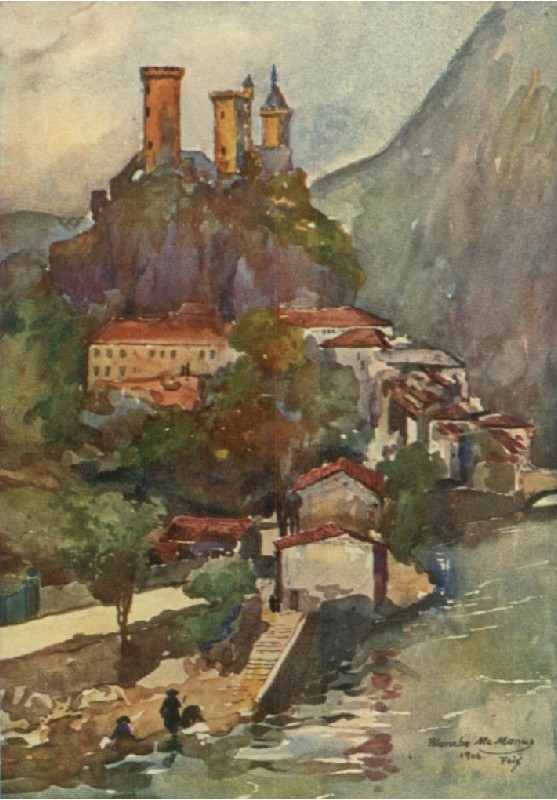

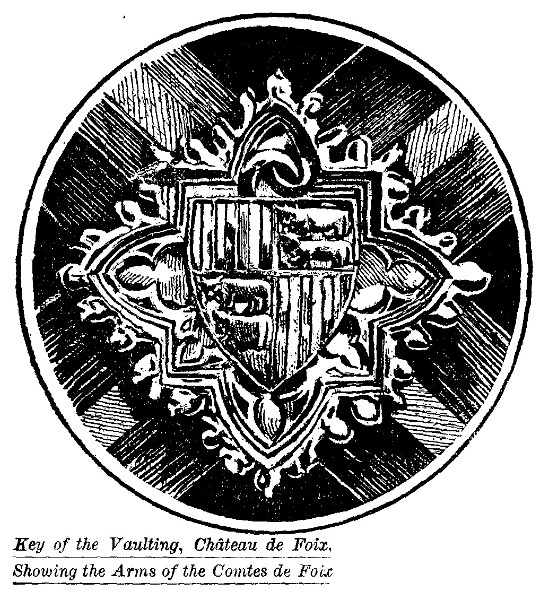

| CHAPTER XI

FOIX AND ITS CHÂTEAU FOIX, of all the Préfectures of France of today, is the least cosmopolitan. Privas, Mende and Digne are poor, dead, dignified relics of the past; but Foix is the dullest of all, although it is a very gem of a smiling, diffident little wisp of a city, green and flowery and astonishingly picturesque. It has character, whatever it may lack in progressiveness, and the brilliant colouring is a part of all the cities of the South. Above the swift flowing Ariège in their superb setting of mountain and forest are the towers and parapets of the old château, in itself enough to make the name and fame of any city. Architecturally the remains of the Château de Foix do not, perhaps, rank very high, though they are undeniably imposing; and it will take a review of Froissart, and the other old chroniclers of the life and times of the magnificent Gaston Phbus, to revive it in all its glory. A great state residence something more than a mere feudal château, it does not at all partake of the aspect of a château-fort. It was this last fact that caused the Comtes de Foix, when, by marriage, they had also become seigneurs of Béarn, to abandon it for Mazères, or their establishments at Pau or Orthez. Foix nevertheless remained a proud capital, first independent, then as part of the province of Navarre, then as a province of the Royaume de France; and, finally, as the Préfecture of the Département of Ariège. The population in later times has grown steadily, but never has the city approached the bishopric of Pamiers, just to the northward, in importance. Many towns in this region have a decreasing population. The great cities like Toulouse and Bordeaux draw upon the youth of the country for domestic employment; and, lately, as chauffeurs and manicurists, and in comparison to these inducements their native towns can offer very little. If one is to believe the tradition of antiquity the "Rocher de Foix," the tiny rock plateau upon which the château sits, served as an outpost when the Phoceans built the primitive château upon the same site. Says a Renaissance historian: "On the peak of one of nature's wonders, on a rock, steep and inaccessible on all sides, was situated one of the most ancient fortresses of our land." In Roman times the site still held its own as one of importance and impregnability. A representation of the château as it then was is to be seen on certain coins of the period. This establishes its existence as previous to the coming of the Visigoths in the beginning of the sixth century. The first written records of the Château de Foix date from the chronicles of 1002, when Roger-le-Vieux, Comte de Carcassonne, left to his heir, Bernard-Roger, "La Terre et le Château de Foix." The Château de Foix owes its reputation to its astonishingly theatrical site as much as to the historic memories which it evokes, though it is with good right that it claims a legendary renown among the feudal monuments of the Pyrenees. All roads leading to Foix give a long vista of its towered and crenelated château sitting proudly on its own little monticule of rock beside the Ariège. Its history begins with that of the first Comtes de Foix, the first charter making mention thereof being the last will and testament of Roger-Bernard, the first count, who died in 1002. During the wars against the Albigeois the château was attacked by Simon de Montfort three times, in 1210, 1212, 1213, but always in vain. Though the surrounding faubourgs were pillaged and burned the château itself did not succumb. It did not even take fire, for its rocky base gave no hold to the flames which burned so fiercely around it. The most important event of the château's history happened in 1272 when the Comte Roger-Bernard III rebelled against the authority of the Seneschal-Royal of Toulouse. To punish so rebellious a vassal, Philippe-le-Hardi came forthwith to Foix at the head of an army, and himself undertook the siege of the château. At the end of three days the count succumbed, with the saying on his lips that it was useless to cut great stones and build them up into fortresses only to have them razed by the first besiegers that came along. Whatever the qualifications of the third Roger-Bernard were, consistent perseverance was not one of them. Just previous to 1215, after a series of intrigues with the church authorities, the château became a dependence of the Pope of Rome; but at a council of the Lateran the Comte Raymond-Roger demanded the justice that was his, and the new Pope Honorius III made over the edifice to its rightful proprietor. During the wars of religion the château was the storm-centre of great military operations, of which the town itself became the unwilling victim. In 1561 the Huguenots became masters of the city. Under Louis XIII it was proposed to raze the château, as was being done with others in the Midi, but the intervening appeal of the governor saved its romantic walls to posterity. In the reign of Louis XIV the towers of the château were used as archives, a prison and a military barracks, and since the Revolution for a part of the time at least it has served as a house of detention. When the tragic events of the Reformation set all the Midi ablaze, and Richelieu and his followers demolished most of the châteaux and fortresses of the region, Foix was exempted by special orders of the Cardinal-Minister himself. Another war cloud sprang up on the horizon in 1814, by reason of the fear of a Spanish invasion; and it was not a bogey either, for in 1811 and 1812 the Spaniards had already penetrated, by a quickly planned raid, into the high valley of the Ariège. In 1825 civil administration robbed this fine old example of mediaeval architecture of many of those features usually exploited by antiquarians. To increase its capacity for sheltering criminal prisoners, barracks and additions mere shacks many of them were built; and the original outlines were lost in a maze of meaningless roof-tops. Finally, a quarter of a century later, the rubbish was cleared away; and, before the end of the century, restoration of the true and faithful kind had made of this noble mediæval monument a vivid reminder of its past feudal glory quite in keeping with its history.  GROUND PLAN OF THE CHÂTEAU DE FOIX The actual age of the monument covers many epochs The two square towers and the main ediface, as seen to-day, are anterior to the thirteenth century, as is proved by the design in the seals of the Comtes de Foix of 1215 and 1241 now in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. In the fourteenth century these towers were strengthened and enlarged with the idea of making them more effective for defence and habitation.  CHÂTEAU DE FOIX The escutcheons of Foix, Béarn and Comminges, to be seen in the great central tower, indicate that it, too, goes back at least to the end of the fourteenth century, when Eleanore de Comminges, the mother of Gaston Phbus, ruled the Comté.  KEY OF THE VAULTING, CHÂTEAU DE FOIX, SHOWING THE ARMS OF THE COMTES DE FOIX The donjon or Tour Ronde arises on the west to a height of forty-two metres; and will be remarked by all familiar with these sermons in stone scattered all over France as one of the most graceful. Legend attributes it to Gaston Phbus; but all authorities do not agree as to this. The window and door openings, the mouldings, the accolade over the entrance doorway and the machicoulis all denote that they belong to the latter half of the fifteenth century. These, however, may be later interpolations. Originally one entered the château from exactly the opposite side from that used to-day. The slope leading up to the rock and swinging around in front of the town is an addition of recent years. Formerly the plateau was gained by a rugged path which finally entered the precincts of the fortress through a rectangular barbican. Finally, to sum it up, the pleasant, smiling, trim little city of Foix, and its château rising romantically above it, form a delightful prospect. Well preserved, well protected, and for ever free from further desecration, the Château de Foix is as nobly impressive and glorious a monument of the Middle Ages as may be found in France, as well as chief record of the gallant days of the Comtes de Foix. Foix' Palais de Justice, built back to back with the rock foundations of the château, is itself a singular piece of architecture containing a small collection of local antiquities. This old Maison des Gouverneurs, now the Palais de Justice, is a banal, unlovely thing, regardless of its high-sounding titles. In the Bibliothèque, in the Hôtel de Ville, there are eight manuscripts in folio, dating from the fifteenth century, and coming from the Cathedral of Mirepoix. They are exquisitely illuminated with miniatures and initials after the manner of the best work of the time. It was that great hunter and warrior, Gaston Phbus who gave the Château de Foix its greatest lustre. It was here that this most brilliant and most celebrated of the counts passed his youth; and it was from here that he set out on his famous expedition to aid his brother knights of the Teutonic Order in Prussia. At Gaston's orders the Comte d'Armagnac was imprisoned here, to be released after the payment of a heavy ransom. As to the motive for this particular act authorities differ as to whether it was the fortunes of war or mere brigandage. They lived high, the nobles of the old days, and Froissart recounts a banquet at which he had assisted at Foix, in the sixteenth century, as follows: "And this was what I saw in the Comté de Foix: The Count left his chamber to sup at midnight, the way to the great salle being led by twelve varlets, bearing twelve illumined torches. The great hall was crowded with knights and equerries, and those who would supped, saying nothing meanwhile. Mostly game seemed to be the favourite viand, and the legs and wings only of fowl were eaten. Music and chants were the invariable accompaniment, and the company remained at table until after two in the morning. Little or nothing was drunk." Froissart's description of the table is simple enough, but he develops into melodrama when he describes how the count killed his own son on the same night a tragic ending indeed to a brilliant banquet. "'Ha! traitor,' the Comte said in the patois, as he entered his sleeping son's chamber; ' why do you not sup with us? He is surely a traitor who will not join at table.' And with a swift, but gentle drawing of his coutel (knife) across his successor's throat he calmly went back to supper." Truly, there were high doings when knights were bold and barons held their sway. They could combat successfully everything but treachery; but the mere suspicion of that prompted them to take time by the forelock and become traitors themselves. Foix has a fête on the eighth and ninth of September each year, which is the delight of all the people of the country round about. Its chief centre is the Allées de Vilote, a great tree-shaded promenade at the base of the château. It is brilliantly lively in the daytime, and fairylike at night, with its trees all hung with great globes of light. A grand ball is the chief event, and the "Quadrille Officiel" is opened with the maire and the préfet at the head. After this comes la fête générale, when the happy southrons know no limit to their gaieties. There are three great shaded promenades, and in each is a ball with its attendant music. It is a Paudemonium; and one has to be habituated to distinguish the notes of one blaring band from the others. The central park is reserved for the country folk, that on the left for the town folk, and that on the right for the nobility. This, at any rate, was the disposition in times past, and some sort of distinction is still made. In suburban Foix, out on the road to Pamiers, is the little village of St. Jean-de-Vergues. It has a history, of course, but not much else. It is a mere spot on the map, a mere cluster of houses on the Grande Route and nothing more. In the days of the Comte Roger-Bernard, however, when he would treat with the king of France, and showed his willingness to become a vassal, its inhabitants held out beyond all others for an "indépendance comtale." They didn't get it, to be sure, but with the arrival of Henri Quatre on the throne of France, the vassalage became more friendly than enforced. |