|

1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

IV.

THE OLD CITY.

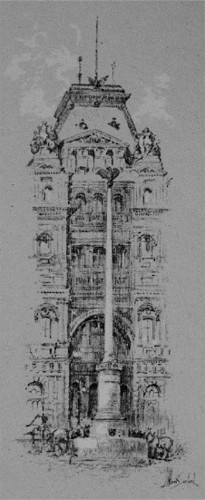

FACADE OF THE GENERAL POST OFFICE; ANGELL MEMORIAL

FOUNTAIN, ERECTED IN HONOR OF THE FOUNDER OF THE

MASSACHUSETTS SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY

TO ANIMALS.

SEVERAL of Governor Winthrop's followers were residents of the old town of Boston, England, and John Cotton, minister of the First Church of Christ, in New England, had been vicar of St. Botolph's church at home. The new settlement on Shawmut promontory was named "Boston" by official decision on September 7, 1630. There was comfort in that, a sort of anchoring finality, whereby the colonists could assure themselves that, at last, they had gotten somewhere.

Winthrop had his first Boston home set up by the path to the waterside from which grew King (now State) street, but subsequently occupied a dwelling on a lot at the present corner of Washington and Milk streets. Beside it was reared the Old South Meeting House. The "Great Spring" boiled from the ground a few steps to the east. All the dwellings were primitively rough. The governor rebuked one of his neighbors who, for the sake of warmth, lined his living-room with a sheathing of plank, in the form of a wainscot. It savored of waste, and sinful pride. The roofs were thatched, very likely with the tough, rank grass or rushes from the salt marshes, and the chimneys were of logs, laid crosswise, and chinked with clay. Later a saw-mill was built on Mill Creek, which connected the Mill Pond with Town Cove, and, as were the grist mills, was actuated by the current of the tide-water. The promontory was not heavily timbered, so most of the lumber must have been floated over from the mainland.

The first volume of town records, so far as we know, was started in September, 1634, in a hand said to be Winthrop's. These records were destroyed or so badly mutilated that no authentic vital statistics of that early period are available. At the end of seventy years the population of Boston did not exceed seven thousand souls. There were disastrous fires, the first in 1654, which wiped out whole groups of dwellings. That of 1678 destroyed eighty houses, and other property, to the value of £200,000. Afterwards, more heed was given the possibility of fires, but brick and stone construction did not become general for many years.

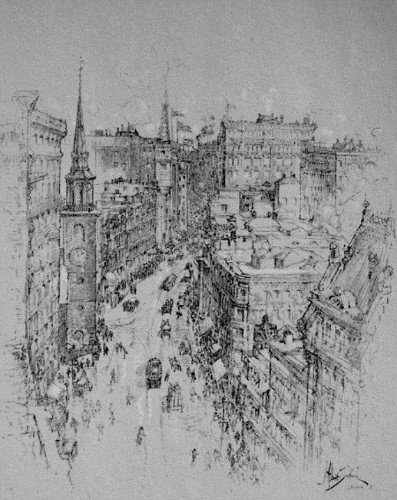

WASHINGTON STREET, LOOKING SOUTH. ON THE LEFT, THE

OLD SOUTH MEETING HOUSE, CORNER OF MILK STREET, BUILT 1729.

AT THE EXTREME LEFT IS THE SITE OF GOVERNOR JOHN WINTHROP'S HOUSE.

The development of the town followed a line north and south, represented, approximately, by the present Washington street. Naturally, too, the settlement clung close to the harbor lip, for in so islanded a location the citizens must depend largely upon maritime traffic for the necessaries as well as for the amenities of life. Communication with Roxbury and the South Shore lay over Boston Neck, a tenuous filament of terra firma, with the stress on the terror, presumably, since persons are known to have perished in trying to follow its treacherous length. Near what is now Dover street, the townsmen set up a rough fortification in view of possible Indian attack. No such assault ever occurred. From this point northward to the present corner of Boylston street the "Highway to Roxbury," now Washington street, was named Orange street; thence to the head of Summer, it was called Newbery; the section from Summer to School was Marlborough; and Corn Hill took up the burden at that point and carried it to the foot of the Cornhill of today, which was then Market street, so-called because it led to the market district about the Town Dock.

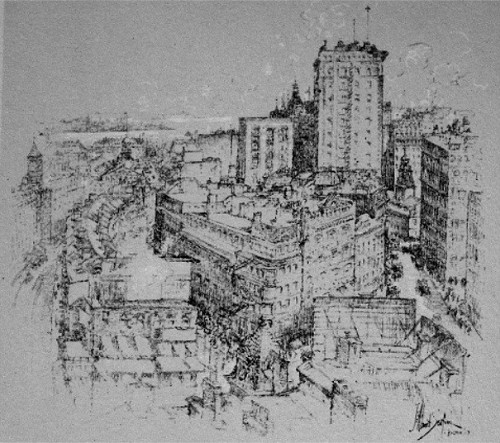

THE OLD CITY FROM PEMBERTON SQUARE. BRATTLE STREET, CORNHILL

AND COURT STREET; AT DISTANT

LEFT, FANEUIL HALL; AT THE RIGHT, THE OLD STATE HOUSE. BEYOND, THE HARBOR, AND

EAST BOSTON.

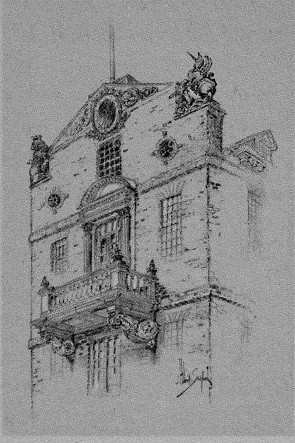

From a ten-story building in Pemberton square, as high as the old Pemberton Hill the location of which it marks, you can look off across a considerable portion of the old city. Pocketed by towering office buildings you see the little Town House, since called the Old State House, holding the head of King (now State) street. There was the market stead, to be replaced by the first Town House, 1657, built by private subscription supplementing a legacy of Captain Robert Keayne, who lived on the corner of King street and Old Corn Hill, just south of it. Captain Keayne commanded the Honorable Artillery Company, today Ancient as well as Honorable, the earliest of our citizen-soldiery. In front of the old Town House you may drink at the city's expense from an automatic fountain; but do not seek a relationship between it and the Town Pump that stood near this point in Colonial times. Fire destroyed the first Town House, which was of wood; and the second, a brick building on the same site, was erected in 1713, to be burned in 1747, with many of its priceless records. The town rebuilt it on the ruins of the old structure, a substantial part of the walls of which had remained in place. Here, at different times, both town and state governments held meetings. The city government used Faneuil Hall for many years, and from 1830 to 1840 met in the Old State House.

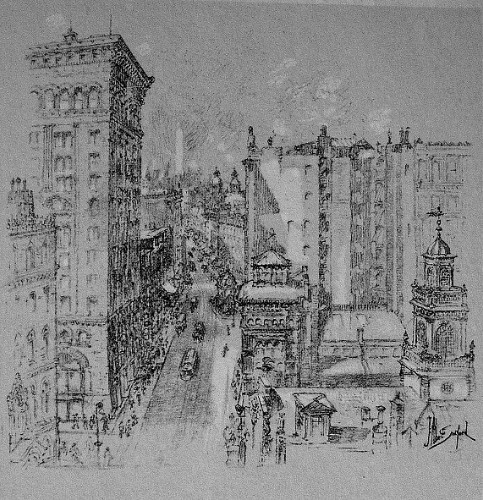

A portion of the North End appears in the view from the top of the Boston Globe building, looking north along Washington street. Again you have a glimpse of the Old State House. Where, at the extreme left, you see the Sears building, John Coggan had a shop, the first in Boston. In those days, if a shopkeeper inclined to elevate the cost of living, his clientele found legal curbs to check his avarice; and our friend Keayne, who was a tailor, "fell under the censure of court and church for selling his wares at exorbitant profits."

WASHINGTON STREET (OLD CORN HILL) LOOKING NORTH.

TOWERS OF ST. MARY'S.

BEYOND, THE NORTH END; BUNKER HILL MONUMENT.

Court street was "Prison Lane," and the old prison gloomed where the tall new office-building of the municipality has lately risen. In this vicinity, in 1719, William Brooker, the postmaster, published the Boston Gazette and employed James Franklin to print it. Afterward, James harked to the buzz of the publishing bee and started the New England Courant. The buzzing annoyed the authorities, and James was enjoined from publishing his paper, so he beat the devil about the stump by permitting young Benjamin, his brother, to attach his name as publisher. This was the third newspaper in Boston, 1721.

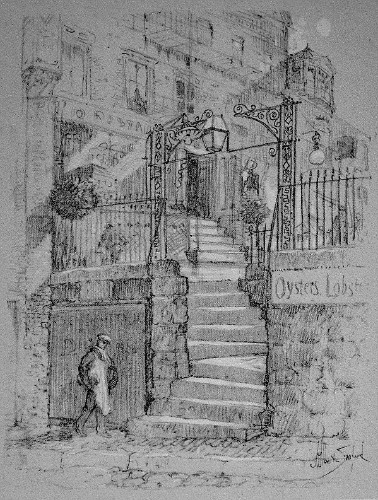

BOSWORTH STREET STEPS INTO PROVINCE STREET, AT THE REAR

OF THE SITE OF THE PROVINCE HOUSE.

The "bigger, better and busier" slogan of recent years would have been equally appropriate if Ben Franklin had thought to apply it to Boston in the columns of his paper, for the community was growing fast, and, as rebuilding succeeded each sweeping conflagration, its architecture and arrangement improved. The characterization "busier" would have been particularly happy. The colonists built houses and warehouses, docks, wharves and fortifications, laid keels and launched ships, trafficked in the commodities of life, talked politics and religion, baited governors -- in fact, conducted themselves much as we do in the matter of hustle and bustle, and, considering what they had to do with, accomplished more.

Regard, as a sample citizen of Provincial days, Colonel Paul Revere. When you know him a little better, you will see that, if lacking Franklin's greatness, he was in many respects not unlike him. Artist, poet, printer, inventor, mechanic, soldier and patriot, Revere was the Leonardo da Vinci of New England. The versatile Leonardo invented the wheelbarrow, Revere devised a gun-carriage; Leonardo painted the "Last Supper," Revere drew rude but graphic caricatures, cartoons of his time, comparable in effect, if not in drawing, to those of Nast or Keppler.

Boston holds one thing against Franklin, namely, his quitting it for Philadelphia; Revere stuck to it. Franklin shed lustre upon Boston by being born here; indeed, if all historians say truly, he doubly honored his native town, since he was born once on Hanover street, near Marshall's Lane and the Boston Stone, and once in a small two-story house on Milk street. Revere plausibly parallels this achievement, nevertheless; for he twice rode to Lexington, and the first of these journeys, though never set to music, was the more important. On Sunday, April 16, he visited Adams and Hancock at the home of Reverend Doctor Clark, reporting what the Sons of Liberty had learned about the British intentions. There was no doubt that the supplies stored at Concord would tempt General Gage, and it remained only to warn the countryside of the exact time of the departure of the troops. This Revere did upon the occasion of the famous dash from Charlestown.

MARSHALL'S LANE; THE BOSTON STONE, FORMERLY PART OF A PAINT

MILL, SET UP IN

1737 AS A WAYMARK. AT THE RIGHT, OFFICE OF EBENEZER HANCOCK, BROTHER OF JOHN

HANCOCK, AND PAYMASTER OF THE REVOLUTION.

William Dawes, stealing out over Boston Neck, reached Lexington half an hour behind Revere, and together they went on, until halted by a mounted British patrol. Dawes got away; so did young Prescott, who had ridden with them from Lexington, and, being a resident of Concord, knew a little-frequented woods path, which he followed to safety, and was so enabled to warn the people of the impending invasion. It is fitting not to forget these two, particularly since to do so subtracts no credit from Revere.

As a matter of fact, Paul Revere made a specialty of the "message-to-Garcia" business. When he had anything to do, he did it, and seems to have been singularly tongue-tied under conditions that would have brought, from most men, protesting questions of "why" and "wherefore." His ambition was to hold a commission in the Continental army; he had to satisfy himself with a militia appointment. When, after the Revolution, under the new government, Patriotism found it necessary to "do something" for poor brother Patronage, Revere would have liked a federal appointment. Congressman Ames, to whom he applied, rendered him the polite equivalent of our latter-day "nothing doing," so the Colonel decided that being a sterling patriot was not nearly so nourishing as the sordid pursuit of trade.

Besides the Midnight Ride, Paul Revere made good his claim to useful citizenship by many and varied activities and achievements. He made copper-plate engravings, drew and engraved at least two harbor-front views of Boston, practised dentistry, fitting false teeth "in such a manner that they are not only an Ornament, but of real Use in Speaking and Eating;" served the patriot cause as official messenger, commanded an artillery train in charge of the Castle (now Fort Independence), invented a gun-carriage at the request of General Washington, imprinted "soldiers' notes," a form of continental tender, kept a goldsmith's shop, established a bell-foundry, engraved the seal of the Commonwealth, manufactured the copper hardware for the frigate "Constitution," and the sheathing with which she was bottomed; also made many tons of copper products for the government, and the sheeting which covered the dome of the new State House on Beacon Hill; and he assisted, as Grand Master of the Freemasons of Massachusetts, in laying the corner stone of that building, July 4, 1795. He lived to be eighty-four years old, and, dying, left a fortune of $35,000, many examples of worthy craftsmanship, an established business, and an honored name.

Revere's house in North square is today, with one possible exception, the oldest standing edifice in Boston; it was built in 1676, and was nearly a century old when Revere became its occupant. About North square dwelt many of the "best families;" in its vicinity were several churches, including the Old North. Today it forms a part of the Italian quarter; is there a future president, think you, playing upon its pavement?

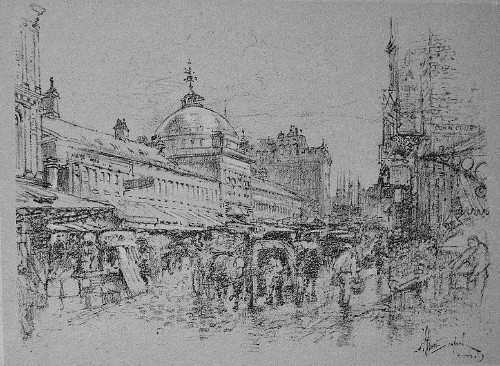

FANUEIL HALL MARKET, BUILT BY JOSIAH QUINCY, 1825, WHERE

FORMERLY

WAS LOCATED THE OLD TOWN DOCK. FREQUENTLY CALLED QUINCY MARKET.

Faneuil Hall was built by Peter Faneuil, at the head of the Town Dock, in 1742. Mill Creek, connecting the Town Dock with the Mill Pond, was later turned into a canal for the passage of small shipping. In 1895 Josiah Quincy built a new market, filling in the old dock, and adding vastly to the commercial facilities of the city.

Near the Boston Stone, in Marshall's Lane, Ebenezer Hancock, Revolutionary paymaster, disbursed the gold, loaned by France, for the payment of the Continental troops; and in this neighborhood Louis Philippe, future king of France, in 1798 gave French lessons at the house of James Ambard.

And so every corner in old Boston has its history and its associations. A single chapter can but suggest, where here or there an incident teases one's imagination or starts the train of reminiscence backtracking along a path as devious as the tangled streets themselves. What of Tremont street, King's Chapel, and that neighborhood of fine estates on the Pemberton slope? What of the Granary Burying Ground, where nine governors sleep, undisturbed by the futile clatter of street noises .above, or the roar of the subway beneath? What of the great Mall, the Haymarket, or the sober luxuries of Colonnade Row? What of the old slough near Boylston street, where the selectmen, deep mired one day, heard the satirical voice of witty Mather Byles, calling from his open door,

"Well, gentlemen, I'm glad to see you stirring in that matter at last."

What, indeed? Let us hasten on, or ourselves be mired in a welter of historic incident.

EAST END OF THE OLD STATE HOUSE, 1713; NOW THE HOME

OF THE BOSTONIAN SOCIETY, ORGANIZED IN 1881 TO PROMOTE

THE STUDY OF THE HISTORY OF BOSTON AND THE PRESERVATION

OF ITS ANTIQUITIES.

Click the book image to continue to the next chapter