| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2016 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER VII

A LEAF FROM THE PAST

In

the Here, then, is a conundrum:

How does it happen that moonshining is distinctly a foible of the southern

mountaineer? To get to the truth, we

must hark back into that eighteenth century wherein, as I have already

remarked, our mountain people are lingering to this day. We must leave the

South; going, first, to The people of

Thae curst horse-leeches o’ the Excise

Wha mak the whisky stills their prize! Haud up thy han’, Deil! ance, twice, thrice! There, seize the blinkers! [wretches] An bake them up in brunstane pies For poor d — n’d drinkers. Perhaps the chief reason,

in Now, there came a time when

the taxes laid upon spirituous liquors had increased almost to the point of

prohibition. This was done, not so much for the sake of revenue, as for the

sake of the public health and morals. Englishmen had suddenly taken to drinking

gin, and the immediate effect was similar to that of introducing firewater

among a race of savages. There was hue and cry (apparently with good reason),

that the gin habit, spreading like a plague, among a people unused to strong

liquors, would soon exterminate the English race. Parliament, alarmed at the

outlook, then passed an excise law of extreme severity. As always happens in

such cases, the law promptly defeated its own purpose by breeding a spirit of

defiance and resistance among the great body of the people. The heavier the tax, the

more widespread became the custom of illicit

distilling. The law was evaded in two different ways, the method depending

somewhat upon the relative loyalty of the people toward the Crown, and somewhat

upon the character of the country, as to whether it was thickly or thinly

settled. In rich and populous

districts, as around However, this sort of thing

was not moonshining. It was only the beginning of that system of wholesale

collusion which, in later times, was perfected in our own country by the

“Whiskey Ring.” Moonshining proper was

confined to the poorer class of people, especially in Ireland, who lived in

wild and sparsely settled regions, who were governed by a clan feeling stronger

than their loyalty to the central Government, and who either could not afford

to share their profits with the gaugers, or disdained to do so. Such people hid

their little pot-stills in inaccessible places, as in the savage mountains and

glens of Thus we see that the

townsman’s weapon against the government was graft, and the mountaineer’s

weapon was his gun — a hundred and fifty years ago, in The north of They were a fighting race.

Accustomed to plenty of hard knocks at home, they took to the rough fare and

Indian wars of our border as naturally as ducks take to water. They brought

with them, too, an undying hatred of excise laws, and a spirit of unhesitating

resistance to any authority that sought to enforce such laws. It was these Scotchmen, in

the main, assisted by a good sprinkling of native Irish, and by the wilder

blades among the Pennsylvania-Dutch, who drove out the Indians from the

Alleghany border, formed our rear-guard in the Revolution, won that rough

mountain region for civilization, left it when the game became scarce and

neighbors’ houses too frequent, followed the mountains southward, settled

western Virginia and Carolina, and formed the vanguard westward into Kentucky,

Tennessee, Missouri, and so onward till there was no longer a West to conquer.

Some of their descendants remained behind in the fastnesses of the Alleghanies,

the The first generation of They were the first

English-speaking people to use weapons of precision (the rifle, introduced by

the Pennsylvania-Dutch about 1700, was used by our backwoodsmen exclusively

throughout the war). They were the first to employ open-order formation in

civilized warfare. They were the first outside colonists to assist their New

England brethren at the siege of  A Tub Mill And yet these same men were the first rebels against

the authority of the United States Government! And it was their old

commander-in-chief, Washington himself, who had the ungrateful task of bringing

them to order by a show of Federal bayonets. It happened in this wise: Up to the year 1791 there

had been no excise tax in the United Colonies or the Western Pennsylvania, and

the mountains southward, had been settled, as we have seen, by the

Scotch-Irish; men who had brought with them a certain fondness for whiskey, a

certain knack in making it, and an intense hatred of excise, on general as well

as special principles. There were few roads across the mountains, and these few

were execrable — so bad, indeed, that it was impossible for the backwoodsmen to

bring their corn and rye to market, except in a concentrated form. The farmers

of the seaboard had grown rich, from the high prices that prevailed during the French Revolution;

but the mountain farmers had remained poor, owing partly to difficulties of

tillage, but chiefly to difficulties of transportation. As Albert Gallatin

said, in defending the western people, “We have no means of bringing the

produce of our lands to sale either in grain or in meal. We are therefore

distillers through necessity, not choice, that we may comprehend the greatest

value in the smallest size and weight. The inhabitants of the eastern side of the

mountains can dispose of their grain without the additional labor of

distillation at a higher price than we can after we have disposed that labor

upon it.” Again, as in all frontier

communities, there was a scarcity of cash in the mountains. Commerce was

carried on by barter; but there had to be some means of raising enough cash to

pay taxes, and to purchase such necessities as sugar, calico, gun powder, etc.,

from the peddlers who brought them by pack train across the Alleghanies.

Consequently a still had been set up on nearly every farm. A horse could carry

about sixteen gallons of liquor, which represented eight bushels of grain, in

weight and bulk, and double that amount in value. This whiskey, even after it

had been transported across the mountains, could

undersell even so cheap a beverage as But when the newly created

Congress passed an excise law, it virtually placed a heavy tax on the poor

mountaineers’ grain, and let the grain of the wealthy eastern farmers pass on

to market without a cent of charge. Naturally enough, the excitable people of

the border regarded such a law as aimed exclusively at themselves. They

remonstrated, petitioned, stormed. “From the passing of the law in January, 1791,

there appeared a marked dissatisfaction in the western parts of Our western mountains (we

call most of them southern mountains now) resembled somewhat those wild

highlands of Connemara to which reference has been

made — only they were far wilder, far less populous, and inhabited by a people

still prouder, more independent, more used to being a law unto themselves than

were their ancestors in old Hibernia. When the Federal exciseman came among

this border people and sought to levy tribute, they blackened or otherwise

disguised themselves and treated him to a coat of tar and feathers, at the same

time threatening to burn his house. He resigned. Indignation meetings were

held, resolutions were passed calling on all good citizens to disobey

the law, and whenever anyone ventured to express a contrary opinion, or rented

a house to a collector, he, too, was tarred and feathered. If a prudent or

ultra-conscientious individual took out a license and sought to observe the

law, he was visited by a gang of “Whiskey Boys” who smashed the still and

inflicted corporal punishment upon its owner. Finally, warrants were

issued against the lawbreakers. The attempt to serve these writs produced an

uprising. On July 16, 1794, a company of mountain militia marched to the house

of the inspector, General Neville, to force him to give up his commission.

Neville fired upon them, and, in the skirmish that ensued, five of the

attacking force were wounded and one was killed. The

next day, a regiment of 500 mountaineers, led by one “Tom the Tinker,” burned

Neville’s house, and forced him to flee for his life. His guard of eleven A call was then issued for

a meeting of the mountain militia at the historic Braddock’s Field. On Aug. 1,

a large body assembled, of whom 2,000 were armed. They marched on On this same day (the

Governor of Pennsylvania having declined to interfere) While negotiations were

proceeding, the army advanced. Eighteen ringleaders of the mob were arrested,

and the “insurrection” faded away like smoke. When the troops arrived, there

was nothing for them to do. The insurgent leaders were tried for treason, and

two of them were convicted, but But Jefferson himself came

to the presidency within six years, and the excise tax was promptly repealed,

never again to be instituted, save as a war measure, until within a time so

recent that it is now remembered by men whom we would not call very old. The moonshiners of our own

day know nothing of the story that has here been written. Only once, within my

knowledge, has it been told in the mountains, and then the result was so

unexpected, that I append the incident as a color contrast to this rather

sombre narrative. — I was calling on a

white-bearded patriarch who was a trifle vain of his historical learning. He

could not read, but one of his daughters read to

him, and he had learned by heart nearly all that lay between the two lids of a

“Universal History” such as book agents peddle about. Like one of John Fox’s

characters, he was fond of the expression “hist’ry says” so-and-so, and he

considered it a clincher in all matters of debate. Our conversation drifted to

the topic of moonshining. “Down to the time of the

Civil War,” declared the old settler, “nobody paid tax on the whiskey he made.

Hit was thataway in my Pa’s time, and in Gran’sir’s, too. And so ’way back to

the time of George Washington. Now, hist’ry says that I murmured a complaisant

assent. “Waal, sir, if ’t was right

to make free whiskey in “But that is where you make

a mistake,” I replied. “ This was news to Grandpa.

He listened with deep attention, his brows lowering as the narrative proceeded.

When it was finished he offered no comment, but brooded to himself in silence.

My own thoughts wandered far afield, until recalled to the topic by a blunt

demand: “You say “He did.” “George Washington?” “Yes, sir: the Father of

his Country.” “Waal, I’m satisfied now

that The law of 1791, although

it imposed a tax on whiskey of only 9 to 11 cents per proof gallon, came near

bringing on a civil war, which was only averted by the leniency of the Federal

Government in granting wholesale amnesty. The most stubborn malcontents in the

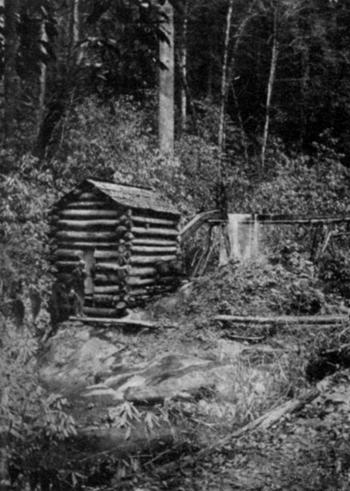

mountains moved southward along the Alleghanies into western  Cabin on the Little Fork of Sugar Fork of Hazel Creek in which the author lived alone for three years On the accession of Then came the Civil War. In

1862 a tax of 20 cents a gallon was levied. Early in 1864 it rose to 60 cents.

This cut off the industrial use of spirits, but did not affect its use as a

beverage. In the latter part of 1864 the tax leaped to $1.50 a gallon, and the

next year it reached the prohibitive figure of $2. The result of such excessive

taxation was just what it had been in the old times, in Seeing that the outcome was

disastrous from a fiscal point of view — the revenue from this source was

falling to the vanishing point — Congress, in 1868, cut down the tax to 50

cents a gallon. “Illicit distillation practically ceased the very hour that the

new law came into operation; ... the Government collected during the second

year of the continuance of the act $3 for every one that was obtained during

the last year of the $2 rate.” In 1869 there came a new

administration, with frequent removals of revenue officials for political

purposes. The revenue fell off. In 1872 the rate was raised to 70 cents, and in

1875 to 90 cents. The result is thus summarized by David A. Wells: “Investigation carefully

conducted showed that on the average the product of illicit distillation costs,

through deficient yields, the necessary bribery of attendants, and the expenses

of secret and unusual methods of transportation, from two to three times as

much as the product of legitimate and legal distillation. So that, calling the

average cost of spirits in the United States 20 cents per gallon, the product

of the illicit distiller would cost 40 to 60 cents, leaving but 10 cents per

gallon as the maximum profit to be realized from fraud under the most favorable conditions — an amount not sufficient to offset the

possibility of severe penalties of fine, imprisonment, and confiscation of property....

The rate of 70 cents... constituted a moderate temptation to fraud. Its

increase to 90 cents constituted a temptation altogether too great for human

nature, as employed in manufacturing and selling whiskey, to resist.... During

1875-6, highwines sold openly in the “Before the war these

simple folks made their apples and peaches into brandy, and their corn into

whiskey, and these products, with a few cattle, some dried fruits, honey,

beeswax, nuts, wool, hides, fur, herbs, ginseng and other roots, and woolen

socks knitted by the women in their long winter evenings, formed the stock in trade

which they bartered for their plain necessaries and few luxuries, their

homespun and cotton cloths, sugar, coffee, snuff, and fiddles.... The raising

of a crop of corn in summer, and the getting out of tan-bark and lumber in

winter, were almost their only resources.... The burden of taxation rested

lightly on them. For near two generations no excise duties had been levied....

The war came on. They were mostly loyal to the “They were willing to pay

any tax that they were able to pay. But suddenly the tax jumped to $1.50, and

then to $2, a gallon. The people were goaded to open rebellion. Their corn at

that time brought only from 25 to 40 cents a bushel; apples and peaches, rarely

more than 10 cents at the stills. These were the only crops that could be grown

in their deep and narrow valleys. Transportation was so difficult, and markets

so remote, that there was no way to utilize the surplus except to distill it.

Their stills were too small to bear the cost of government supervision. The

superior officers of the Revenue Department (collectors, marshals, and

district-attorneys or commissioners) were paid only by commissions on

collections and by fees. Their subordinate agents, whose income depended upon

the number of stills they cut up and upon the arrests made, were, as a class,

brutal and desperate characters. Guerrilla warfare was the natural sequence.” _______________ 7 Ellwood Wilson, Sr., in

the Sewanee Review. |