| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2016 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER XV

THE BLOOD-FEUD

In

“Before the law made us

citizens, great Nature made us men.” “When one has an enemy, one

must choose between the three S’s — schiopetto, stiletto, strada: the

rifle, the dagger, or flight.” “There are two presents to

be made to an enemy — palla calda o ferro freddo: hot shot or cold

steel.” The Corsican code of honor

does not require that vengeance be taken in fair fight. Rather should there be

a sudden thrust of the knife, or a pistol fired point-blank into the enemy’s

breast, or a rifle-shot from some ambush picked in advance. The assassin is not

conscious of any cowardice in such act. If the trouble between him and his foe

had been strictly a personal matter, to be settled

forever by one man’s fall, then he might have welcomed a duel with all the

punctilios. But his blood is not his alone — it belongs to his clan. Whenever a

Corsican is slain his family takes up the feud. A vendetta ensues — a war of

extermination by clan against clan. Now, the chief object of

war, as all strategists agree, is to inflict the greatest loss upon the enemy

with the least loss to one’s own side. Hence we have hostilities without

declaration of war; we have the ambush, the night attack, masked batteries,

mines and submarines. Thus we murder hundreds asleep or unshriven. This is war.

Moreover, while a soldier

must be brave in any extremity, it is no less his duty to save himself unharmed

as long as he can, so that he may help his own side and kill more and more of

the enemy. Therefore it is proper and military for him to “snipe” his foes by

deliberate sharpshooting from behind any lurking-place that he can find. This

is war. And the vendetta, says our

Corsican, is nothing else than war. When Matteo has been slain

by an enemy, his friends carry his body home and swear vengeance over the

corpse, while his wife soaks her handkerchief in his wounds to keep as a token whereby she will incite her children, as they grow up, to

war against all kinsmen of their father’s murderer. Then a son or brother of

Matteo slips forth into the night, full-armed to slay like a dog any member of

the rival faction whom he may find at a disadvantage. The deed done, he flies

to the maquis, the mountain thicket, and there he will hide, dodging the

gendarmes, fighting off his enemies — an outlaw with a price upon his head, but

pitied or admired by all Corsicans outside the feud, and succored by his clan. It is a far cry from the

Mediterranean to our own Long, long ago, in the

mountains of eastern Afterwards Baker returned.

In flat violation of the Constitution of the In 1898, Tom Baker, reputed

to be the best shot in the Thereupon Jim Howard, son

of the clan chief, sought out Tom Baker’s father, who was county attorney,

compelled the unarmed old man to fall upon his knees, shot him twenty-five

times with careful aim to avoid a vital spot, and so killed him by inches.

Howard was tried and convicted of murder, but it is said that a pardon was

offered him if he would go to the State Capitol at In Governor Bradley sent State

troops into I quote now from a history

of this feud published in Munsey’s Magazine of November, 1903. — “Captain John Bryan, of the

2d “‘Mrs. Baker, why don’t you

leave this miserable country and escape from these terrible feuds? Move away,

and teach your children to forget.’ “‘Captain Bryan,’ said the

widow, and she spoke evenly and quietly, ‘I have twelve sons. It will be the

chief aim of my life to bring them up to avenge their father’s death. Each day

I shall show my boys the handkerchief stained with his blood, and tell

them who murdered him.’” Corsican vendetta or Shortly after Baker’s

death, four Griffins, of the White-Howard faction, ambushed Big John Philpotts

and his cousin, wounding the former severely and the latter mortally. Big John

fought them from behind a log and killed all four. On July 17, 1899, four of

the Philpotts were attacked by four Morrises, of the Howard side. Three men

were killed, three mortally wounded, and the other two were severely injured.

No arrests were made. Finally, in 1901, the two

clans fought a pitched battle in front of the court-house in This is a mere scenario of

a feud in the wealthiest and best-schooled county of eastern In reviewing this feud,

Governor Bradley stated: “The whole fault in “The laws are insufficient

for the Governor to apply a remedy.” One naturally asks, “How so?” The answer

is that the Governor cannot send troops into a county except upon request of

the civil authorities, and they must go as a posse to civil officers. In most

feuds these officers are partisans (in fact, it is a favorite ruse for one clan to win or usurp the county offices before

making war). Hence the State troops would only serve as a reinforcement to one

of the contending factions. To show how this works out, we will sketch briefly

the course of another feud. — In As usual, in feuds, no

immediate redress was attempted, but the injured clan plotted its vengeance

with deadly deliberation. After five months, Dick Martin killed Floyd Toliver.

His own people worked the trick of arresting him themselves and sent him to The leader of the

Young-Toliver faction was a notorious bravo named Craig Toliver. To strengthen

his power he became candidate for town marshal of

Morehead, and he won the office by intimidation at the polls. Then, for two

years, a bushwhacking war went on. Three times the Governor sent troops into In 1887, Proctor Knott,

Governor of Kentucky, said in his message, of the Logan-Toliver feud: “Though composed of only a

small portion of the community, these factions have succeeded by their violence

in overawing and silencing the voice of the peaceful element, and in

intimidating the officers of the law. Having their origin partly in party

rancor, they have ceased to have any political significance, and have become

contests of personal ambition and revenge; each party seeking apparently to

possess itself of the machinery of justice in order that it may, under the

forms of law, seek the gratification of personal animosities. “During the present year

the local leader of one of these factions came in possession of the office of

police judge of the town of “This act of atrocity fully

aroused the community. A posse acting under the authority of a warrant from the

county judge attacked the police judge and his adherents on the 22d of June

last, killed several of their number, and put the rest to flight, and

temporarily restored something like tranquility to the community. “The proceedings of the

Circuit Court, which was held in August, were not calculated to inspire the

citizens with confidence in securing justice. The report of the Adjutant

General on this subject shows, from information derived ‘from representative

men without reference to party affiliations,’ that the judge of the Circuit

Court seems so far under the influence of the reputed leader of one of the

factions as to permit such an organization of the grand juries as will

effectually prevent the indictment of members of that faction for the most

flagrant crimes.” The posse here mentioned

was organized by Daniel Boone Logan, a cousin of the two young men who had been

murdered, a college graduate, and a lawyer of good standing. With the assent of

the Governor, he gathered fifty to seventy-five picked men and armed them with

the best modern rifles and revolvers. Some of the men were of his own clan; others he

hired. His plan was to end the war by exterminating the Tolivers. The posse, led by

Logan and the sheriff, suddenly surrounded the town of Boone Logan was indicted

for murder. At the trial he admitted the killings; but he showed that the feud

had cost the lives of not less than twenty-three men, that not one person had

been legally punished for these murders, and that he had acted for the good of

the public in ending this infamous struggle. The court accepted this view of

the case, the community sustained it, and the “war” was closed. A feud, in the restricted

sense here used, is an armed conflict between families, each endeavoring to

exterminate or drive out the other. It spreads swiftly not only to blood-kin

and relatives by marriage, but to friends and retainers as well. It may lie

dormant for a time, perhaps for a generation, and then burst forth with

recruited strength long after its original cause has ceased to interest anyone,

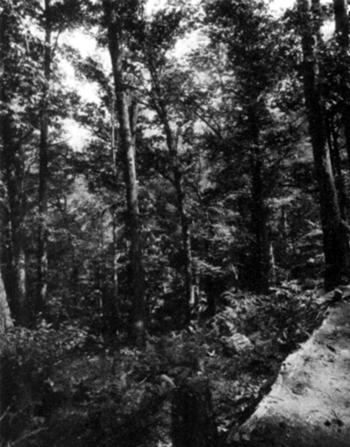

or maybe after it has been forgotten.  Photo by U. S. Forest Service “Dense forest luxuriant undergrowth.” — Mixed hardwoods, Jackson Co., N. C. Such feuds are by no means

prevalent throughout the length and breadth of Appalachia, but are restricted

mostly to certain well defined districts, of which the chief, in extent of

territory as well as in the number and ferocity of its “wars,” is the country

round the upper waters of the Kentucky, Licking, Big Sandy, Tug, and Cumberland

rivers, embracing many of the mountain counties of eastern Kentucky and

adjoining parts of West Virginia, Old Virginia, and Tennessee. In this thinly

settled region probably five hundred men have been slain in feuds since our

centennial year, and only three of the murderers, so far as I know, have been

executed by law. The active feudists, as a

rule, include only a small part of the community; but public sentiment, in feud

districts, approves or at least tolerates the vendetta, just as it does in When a feud is raging,

nobody outside the warring clans is in any danger at all. A stranger is safer

in the heart of Feuddom than he would be in What causes feuds? Some of them start in mere

drunken rows or in a dispute over a game of cards; others in quarrels over land

boundaries or other property. The Hatfield-McCoy feud started because Randolph

McCoy penned up two wild hogs that were claimed by Floyd Hatfield. The spite

over these hogs broke out two years later, and one partisan was killed from

ambush. The feud itself began in 1882 over a debt of $1.75, with the hogs and

the bushwhacking brought up in recrimination. Love of women is the primary

cause, or the secondary aggravation, of many a feud. Some of the most

widespread and deadliest vendettas have originated in political strifes. It should be understood

that national and state politics cut little or no figure in these “wars.” Local

politics in most of the mountain counties is merely

a factional fight, in which family matters and business interests are involved,

and the contest becomes bitterly personal on that account. This explains most

of the collusion or partisanship of county officers and their remissness in

enforcing the law in murder cases. Family ties or political alliances override

even the oath of office. Within the past year I have

heard a deputy sheriff admit nonchalantly, on the stand, that when a homicide

was committed near him, and he was the only officer in the vicinity, he advised

the slayer to take to the mountains and “hide out.” The judge questioned him

sharply on this point, was reassured by the witness that it was so, and then —

offered no comment at all. Within the same period, in another but not distant

court, a desperado from the Shelton Laurel, on trial for murder, admitted that

he had shot six men since he moved over from Tennessee to North Carolina, and

swore that while he was being held in jail pending trial for this last offense

the sheriff permitted him to “keep a gun in his cell, drink whiskey in the

jail, and eat at table with the family of the sheriff.” Feuds spread not only

through clan fealty but also because they offer excellent chances to pay off

old scores. The mountaineer has a long memory. The

average highlander is fiery and combative by nature, but at the same time

cunning and vindictive. If publicly insulted he will strike at once, but if he

feels wronged by some act that does not demand instant retaliation he will

brood over it and plot patiently to get his enemy at a disadvantage. Some

mountaineers always fight fair; but many of them prefer to wait and watch

quietly until the foe gets drunk and unwary, or until he is engaged in some

illegal or scandalous act, or until he is known to be carrying a concealed

weapon, whereupon he can be shot down unexpectedly and his assailant can

“prove” by friendly witnesses that he acted in self-defense. So, if a man be

involved in feud, he may be assassinated from ambush by someone who is not

concerned in the clan trouble, but who has hated him for years on another

account, and who knows that his death now will be charged up to the opposing

faction. From the earliest times it

has been customary for our highlanders to go armed most of the time. This was a

necessity in the old Indian-fighting days, and throughout the kukluxing and

white-capping era following the Civil War. Such a habit, once formed, is hard

to eradicate. Even to-day, in all parts of Among them I have never

seen a stand-up and knock-down fight according to the rules of the ring. They

have many rough-and-tumble brawls, in which they slug, wrestle, kick, bite,

strangle, until one gets the other down, whereat the one on top continues to

maul his victim until he cries “Enough!” Oftener a club or stone will be used

in mad endeavor to knock the opponent senseless at a blow. There is no

compunction about striking foul and very little about “double-teaming.” Let us

pause long enough to admit that this was the British and American way of

man-handling, universal among the common people, until well into the nineteenth

century — and the mountaineers are still ignorant of any other, except fighting

with weapons. Many of the young men carry

home-made billies or “brass knucks.” Every man and boy has at least a

pocket-knife with serviceable blade. Fights with such crude weapons are

frequent. There are few spectacles more sickening than two powerful but awkward

men slashing each other with common jack-knives, though the fatalities are much

less frequent than in gun-fighting. I have known two old mountain preachers to draw knives on each other at the close of a sermon. The typical highland bravo

always carries a revolver or an automatic pistol. This is likely to be a weapon

of large bore and good stopping-power that is worn in a shoulder-holster

concealed under the coat or vest or shirt. Most mountaineers are good shots

with such arms, though not so deadly quick as the frontiersmen of our old-time

West — in fact, they cannot be so quick without wearing the weapon exposed.

When a highlander has time, he prefers to hold his pistol in both hands (left

clasped over right) and aims it as he would a rifle. To a Westerner such gun

practice looks absurd; but it is accurate, beyond question. Few mountain

gun-fights fail to score at least one victim. The average mountain woman

is as combative in spirit as her menfolk. She would despise any man who took

insult or injury without showing fight. In fact, the woman, in many cases,

deliberately stirs up trouble out of vanity, or for the sheer excitement of it.

Some of the older women display the ferocity of she-wolves. The mother of a

large family said in my presence, with the calm earnestness of one fully

experienced: “If a feller ’d treated me the way

——— did ———

I’d git me a forty-some-odd and shoot enough meat

off o’ his bones to feed a hound-dog a week.” Three of this woman’s brothers

had been shot dead in frays. One of them killed the first husband of her

sister, who married again, and whose second husband was killed by a man with

whom she then tried a third matrimonial venture. Such matters may not be

interesting in themselves, but they give one pause when he learns, in addition,

that these people are received as friends and on a footing of equality by

everybody in their community. That the mountaineers are

fierce and relentless in their feuds is beyond denial. A warfare of

bushwhacking and assassination knows no refinements. Quarter is neither given

nor expected. Property, however, is not violated, and women are not often

injured. There have been some atrocious exceptions. In the Hatfield-McCoy feud,

Cap Hatfield and Tom Wallace attacked the latter’s wife and her mother at

night, dragged both women from bed, and Cap beat the old woman with a cow’s

tail that he had clipped off “jes’ to see ’er jump.” He broke two of the

woman’s ribs, leaving her injured for life, while Tom beat his wife. Later, on

New Year’s night, 1888, a gang of the Hatfields surrounded the home of Randolph

McCoy, killed the eldest daughter, Allaphare, broke her mother’s ribs and

knocked her senseless with their guns, and killed a son, Calvin. In several

instances women who fought in defense of their homes have been killed, as in

the case of Mrs. Charles Daniels and her 16-year-old daughter, in The mountain women do not

shrink from feuds, but on the contrary excite and cheer their men to desperate

deeds, and sometimes fight by their side. In the French-Eversole feud, a woman,

learning that her unarmed husband was besieged by his foes, seized his rifle,

filled her apron with cartridges, rushed past the firing-line, and stood by her

“old man” until he beat his assailants off. When men are “hiding out” in the

laurel, it is the women’s part, which they never shirk, to carry them food and

information. In every feud each clan has

a leader, a man of prominence either on account of his wealth or his political

influence or his shrewdness or his physical prowess. This leader’s orders are

obeyed, while hostilities last, with the same unquestioning loyalty that the

old Scotch retainer showed to his chieftain. Either the leader or someone

acting for him supplies the men with food, with weapons if they need them, with

ammunition, and with money. Sometimes mercenaries are hired. Mr. Fox says that

“In one local war, I remember, four dollars per day

were the wages of the fighting man, and the leader on one occasion, while besieging

his enemies — in the county court-house — tried to purchase a cannon, and from

no other place than the State arsenal, and from no other personage than the

Governor himself.” In some of the feuds professional bravos have been employed

who would assassinate, for a few dollars, anybody who was pointed out to them,

provided he was alien to their own clans. The character of the

highland bravo is precisely that of the western “bad man” as pictured by Jed

Parker in Stewart Edward White’s Arizona Nights: “‘There’s a good deal of

romance been written about the “bad man,” and there’s about the same amount of

nonsense. The bad man is just a plain murderer, neither more nor less. He never

does get into a real, good, plain, stand-up gun-fight if he can possibly help

it. His killin’s are done from behind a door, or when he’s got his man dead to

rights. There’s Sam Cook. You’ve all heard of him. He had nerve, of course, and

when he was backed into a corner he made good; and he was sure sudden death

with a gun. But when he went out for a man deliberate, he didn’t take no

special chances.... “‘The point is that these

yere bad men are a low-down, miserable proposition, and plain, cold-blooded

murderers, willin’ to wait for a sure thing, and without no compunctions whatever. The bad man takes you unawares, when you’re

sleepin’, or talkin’, or drinkin’, or lookin’ to see what for a day it’s goin’

to be, anyway. He don’t give you no show, and sooner or later he’s goin’ to get

you in the safest and easiest way for himself. There ain’t no romance about

that.’” And there is no romance

about a real mountain feud. It is marked by suave treachery, “double-teaming,”

“laywaying,” “blind-shooting,” and general heartlessness and brutality. If one

side refuses to assassinate but seeks open, honorable combat, as has happened

in several feuds, it is sure to be beaten. Whoever appeals to the law is sure

to be beaten. In either case he is considered a fool or a coward by most of the

countryside. Our highlander, untouched by the culture of the world about him,

has never been taught the meaning of fair play. Magnanimity to a fallen foe he

would regard as sure proof of an addled brain. The motive of one who forgives

his enemy is utterly beyond his comprehension. As for bushwhacking, “Hit’s as

fa’r for one as ’tis for t’other. You can’t fight a man fa’r and squar who’ll

shoot you in the back. A pore man can’t fight money in the courts.” In this he

is simply his ancient Scotch or English ancestor born over again. Such was the

code of Jacobite Scotland and Tudor England. And back

there is where our mountaineer belongs in the scale of human evolution. The feud, as Miss Miles

puts it, is an outbreak of perverted family affection. Its mainspring is

an honorable clan loyalty. It is a direct consequence of the clan organization

that our mountaineers preserve as it was handed down to them by their

forefathers. The implacability of their vengeance, the treacheries they

practice, the murders from ambush, are invariable features of clan warfare

wherever and by whomsoever it is waged. They are not vices or crimes peculiar

to the Kentuckian or the Corsican or the Sicilian or the Albanian or the Arab,

but natural results of clan government, which in turn is a result of isolation,

of physical environment, of geographical position unfavorable to free

intercourse and commerce with the world at large. The most hideous feature of

the feud is the shooting down of unarmed or unwarned men. Assassination, in our

modern eyes, is the last and lowest infamy of a coward. Such it truly is, when

committed in the civilized society of our day. But in studying primitive races,

or in going back along the line of our own ancestry to the civilized society of

two centuries ago, we must face and acknowledge the strange paradox of a valorous and honorable people (according to their

lights) who, in certain cases, practiced assassination without compunction and,

in fact, with pride. History is red with it in those very “richest ages of our

race” that Professor Shaler cited. Until a century or two ago, throughout

Christendom, the secret murder of enemies was committed unblushingly by nobles

and kings and prelates, often with a pious “Thus sayeth the Lord!” It was

practiced by men valiant in open battle, and by those wise in the counsels of

the realm. Take “No tenet nor practice, no

influence nor power nor principality in the “For centuries such justice

as was exercised was haphazard and rude, and practically there was no law but

the will of the stronger. Few, if any, of the great families but had their

special feud; and feuds once originated survived for ages; to forget them would

have been treason to the dead, and wild purposes of revenge were handed down

from generation to generation as a sacred legacy. “To take an enemy at a

disadvantage was not deemed mean and contemptible, but — ‘Of

all the arts in which the wise excel To do it boldly and

adroitly was to win a peculiar halo of renown; and thus assassination ceased to

be the weapon of the avowed desperado, and came to be wielded unblushingly not

only by so-called men of honor, but by the so-called religious as well. A noble

did not scruple to use it against his king, and the king himself felt no

dishonor in resorting to it against a dangerous noble. James I. was hacked to

death in the night by Sir Robert Graham; and James I. rid himself of the

imperious and intriguing Douglas by suddenly stabbing him while within his own

royal palace under protection of a safe conduct. “The leaders of the

Reformation discerned in assassination (that of their enemies) the special

‘work and judgment of God.’... When the assassination of Cardinal Beaton took

place in 1546, all the savage details of it were set down by Knox with

unbridled gusto. ‘These things we wreat mearlie,’ is his own ingenuous comment

on his performance. “The burden of George

Buchanan’s De Jure Regni apud Scotos is the lawfulness or righteousness

of the removal — by assassination or any other fitting or convenient means — of

incompetent kings, whether heinously wicked and tyrannical or merely unwise and

weak of purpose; and he cites as a case in point and an ‘example in time

coming,’ the murder of James III., which, if it were only on account of the

assassin’s hideous travesty of the last offices of the Church, would deserve to

be held in unique and everlasting detestation.” —

(Henderson, Old-world Scotland, 182-186.) Yet the Scots have always

been a notably warlike and fearless race. So, too, are our southern

mountaineers: in the Civil War and the Spanish War they sent a larger proportion

of their men into the service than almost any other section of our country. Let us not overlook the

fact that it demands courage of a high order for one to stay in a feud-infested

district, conscious of being marked for slaughter — stay there month in and

month out, year in and year out, not knowing at what moment he may be beset by

overpowering numbers, from what laurel thicket he may be shot, or at what hour

of the night he may be called to his door and struck dead before his family. On

the credit side of their valor, then, be it entered that few mountaineers will

shrink from such ordeal when, even from no fault of their own, it is thrust

upon them. The blood-feud is simply a

horrible survival of medievalism. It is the highlander’s misfortune to be stranded

far out of the course of civilization. He is no worse than that bygone age that

he really belongs to. In some ways he is better. He is far less cruel than his

ancestors were — than our ancestors were. He does not torture

with the tumbril, the stocks, the ducking-stool, the pillory, the

branding-irons, the ear-pruners and nostril-shears and tongue-branks that were

in everyday use under the old criminal code. He does not tie a woman to the

cart’s tail and publicly lash her bare back until it streams with blood, nor

does he hang a man for picking somebody’s pocket of twelve pence and a

farthing. He does not go slumming in bedlam, paying tuppence for the sport of

mocking the maniacs until they rattle their chains in rage or horror. He does

not turn executions of criminals into public festivals. He never has been known

to burn a condemned one at the stake. If he hangs a man, he does not first draw

his entrails and burn them before his eyes, with a mob crowding about to jeer

the poor devil’s flinching or to compliment him on his “nerve.” Yet all these

pleasantries were proper and legal in Christian Britain two centuries ago. This isolated and belated

people who still carry on the blood-feud are not half so much to blame for such

a savage survival as the rich, powerful, educated, twentieth-century nation

that abandons them as if they were hopelessly derelict or wrecked. It took but

a few decades to civilize Scotland. How much swifter and surer and easier are

our means of enlightenment to-day! Let us not forget

that these highlanders are blood of our blood and bone of our bone; for they

are old-time Americans to a man, proud of their nationality, and passionately

loyal to the flag that they, more than any other of us, according to their

strength, have fought and suffered for. |