| Web

and Book design, |

Click

Here to return to |

PARK STREET

IN 1708 Sentry (now Park Street) was officially known as the highway extending from Common (now Tremont) Street, up Sentry Hill, to the former head of Temple Street, within the State-House grounds. It was sometimes called Century Street, and the exact time of the adoption of the name Park Street is uncertain. This name, however, appears on Carleton’s Plan of the Town, attached to the first Boston Directory in 1789. And in 1800 Park Street was shown as extending from the Granary at the foot of Common Street to the Almshouse on Beacon Street. At that period, we are told, the appearance of the now thriving thoroughfare was unattractive, with its row of old, dingy public buildings and dilapidated fences. In 1803 or thereabout this highway was laid out anew by Bulfinch, and was then called Park Place. But its present name soon after came into general use. All this region was for some eighty years a part of the Common. In 1813 Park Street was mentioned as leading from the head of Tremont Street Mall to the State House. Park Street Mall dates from 1826, and the iron fence surrounding the Common was built ten years later.

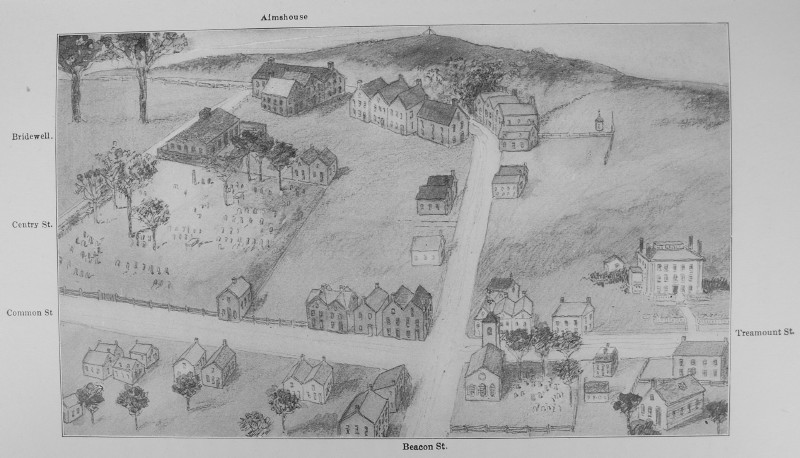

PARK, BEACON AND TREMONT STREETS IN 1722

A section of an Ideal Sketch drawn from Bonner's Map and the Surveys in the City Engineer's Office of Boston

On

Bonner’s Map of 1722 more than a dozen houses are shown within the irregular

quadrilateral bounded by Tremont, Park, and Beacon Streets. Yet on William

Burgiss’s map, of about the year 1728, but three houses appear on this same

territory; and these were on the site of the present Tremont Building.1

Before

its improvement by Bulfinch, as already mentioned, Park Street appears to have

received little attention. It was described as a narrow, vagrant lane,

ill-defined and tortuous, Which had not been accepted by the Town.

Indeed,

the locality was said to have been hardly respectable before the appearance of

Mr. George Ticknor, and the building of his fine mansion-house, “which was to

dignify and illumine the region at the head of the street.” And it is a happy

circumstance that this former mansion-house, although long since enlarged and

given over to business uses, yet stands as a reminder of its old-time supremacy

as a pioneer of respectability for the neighborhood.

“The site

formerly occupied by the Granary and Almshouse,” wrote Shubael Bell in 1817,

“is called Park Place, composed of a range of elegant, lofty buildings, in an

improved style of architecture, after the modern, English models. The upper end

of Park Place is terminated by a stately mansion, which will long be remembered

as the residence of that accomplished gentleman and able statesman, our late

Governor, Christopher Gore. A superb meeting-house makes the lower corner, and

the appearance from the Common has a fine effect. The venerable mansion of

Hancock in Beacon Street remains as it was, aloof from modern improvements.

This street is now lined with elegant buildings down to the Bay, which have a

compleat view of the Common in front, and an extensive prospect of the scenery

beyond Charles River, which nature formed delightful, and art has greatly

embellished.”2

The famous coast, over whose icy incline the Boston

boys were wont to slide, had been in use for this popular sport from an early

period. It extended easterly from just below the crest of Beacon Hill, near the

present Unitarian Building, down Beacon and School Streets, as far as

Washington Street. Affixed to the iron fence in front of the City-Hall grounds

is a bronze tablet, which was placed there by the Boston Chapter of the Sons of

the American Revolution in 1907. The tablet bears the following inscription:

“Here stood the house occupied in 1774-1775 by General Frederick Haldiman, to

whom the Latin School boys made protest against the destruction of their coast.

He ordered the coast restored, and reported the affair to General Gage, who

observed that it was impossible to beat the notion of Liberty out of the

people, as it was rooted in them from their childhood.” The boys’ complaint is

said to have been tactfully worded. They maintained that the sport of coasting

was one of their inalienable rights, sanctioned by custom from time immemorial.

General Haldiman was prompt in yielding to their demand; and ordered his

servant not only to remove the ashes from their coast, but also to water it on

cold nights.

In the

“fifties” of the last century the “Long Coast” extended from the corner of Park

and Beacon Streets to the former West Street Gate of the Common, “and as much

farther as one’s impetus would carry him.” James D’Wolf Lovett, in his

fascinating volume, entitled “Old Boston Boys, and the Games they Played,”

gives a vivid account of the sport of coasting in those days; a pastime which

was keenly relished by many of his contemporaries.

Even

after Boston became a city, Park Street was in a neglected condition, as is

evident from a petition addressed by the residents to the Mayor and Aldermen,

and dated June 20, 1823. The petitioners represented that no common sewer had

ever existed in Park Street, and that the drains there emptied into a hogshead

placed in the middle of the roadway. This receptacle was said to be connected

by pipes with the old Almshouse and Workhouse drains. Within two years the

hogshead had twice burst open during the hot season, “to the great annoyance of

passengers, and great danger to the health of the good citizens of Boston.”

Moreover, the petitioners expressed the opinion that the decomposition of

vegetable substances and the effluvia from bad drains were chief causes of the

diseases peculiar to cities. They therefore requested the authorities to adopt

such measures as would abate the nuisance, so that the atmosphere might retain

its purity, and that the health of the community might be safeguarded. In a

second petition, dated March 30, 1824, it was stated that Park Street was much

out of repair, and that a new roadway was urgently needed.

At a

meeting of the Board of Aldermen, November 18, 1824, a petition was received

from Thomas H. Perkins, Esq., and other residents, who desired that Park Street

should be widened. And later a committee reported that they had “examined the

lower end of Park Street, and found it to be a dangerous corner for carriages

or sleighs, especially in winter.” And they respectfully reported that “if the

proprietors of estates bounding on said Park Street will relay their sidewalks,

and place them upon a regular line of ascent from said Park Street to Beacon

Street, it will be expedient for the City to repair said street upon the McAdam

principle.”

Bliss

Perry, A.M., LL.D., a former editor of the “Atlantic Monthly,” thus wrote in

“Park Street Papers,” 1908: “And what and where is Park Street? It is a short,

sloping, prosperous little highway, in what Rufus Choate called ‘our

denationalized Boston Town.’ It begins at Park Street Church, on Brimstone

Corner. Thence it climbs leisurely westward toward the Shaw Memorial and the

State House for twenty rods or so, and ends at the George Ticknor house on the

corner of Beacon. The street is bordered on the south by the Common; and its

solid-built, sunward-fronting houses have something of a holiday air; perhaps

because the green, outdoor world lies just at their feet. They are mostly given

over, in these latter days, to trade. The habitual passer is conscious of a

pleasant blend of book-shops, flowers, prints, silver-ware, Scotch suitings,

more books, more prints, a Club or two, a Persian rug,--and then Park Street is

behind him.... Sunny windows look down upon the mild activities of the roadway

below; to the left upon the black lines of people streaming in and out of the

Subway; and in front toward the Common with its Frog Pond gleaming through the

elms.”

In June,

1808, the Selectmen authorized the construction of a paved gutter along Park

Street, “to prevent the wash from the upper streets doing damage to the

Common.”

In 1824

Mayor Josiah Quincy, the elder, sometimes called “the Great Mayor,” caused the

removal of a row of unsightly poplar trees, which then lined Park Street Mall.

And with his own hands he is said to have planted American elms in their stead.

The latter grew to stately proportions. Within a few years, however, many of

these beautiful elms have had to yield to the ravages of age, ice-storms, moths

and beetles.

Park

Street Mall was formerly called the “Little Mall,” to distinguish it from the

“Great Mall,” alongside Tremont Street.

About

sixty years ago an old blind man kept a movable cigar-stand on the Common, near

the massive granite gate-posts, which then stood at the lower corner of Park

Street. Here could be bought so-called cinnamon cigars, that had a seductive,

spicy flavor, that probably yet lingers in the memory of a good many “Old

Boston Boys.” This same corner has become a favorite rendezvous for pigeons,

whose numbers seem to increase each year. They are all plump and sleek, and

seem to be on excellent terms with the multitude of people who patronize the

subway route. Any attempt to molest them, or the very tame grey squirrel

habitués of the Common, would offend public sentiment; and the pigeons and squirrels

appear to be fully aware of this fact.

Tremont

Street Mall, between Park and West Streets, presented a lively scene on

Election Days during the early years of the nineteenth century. For, alongside

the old wooden fence, which then bordered the Common, were to be seen long rows

of stands and push-carts, whose proprietors offered for sale divers kinds of

refreshments, of varied degrees of indigestibility. Among these delectable

foodstuffs were lobsters, oysters, doughnuts, cookies, waffles, buns, seedcakes,

candy, baked beans, hot brown bread, ginger beer, lemonade, and spruce beer.

Some of the venders were colored women, who wore bright-hued bandannas around

their heads, after the Southern fashion.3 Mr. Edward Stanwood, in

his article on the “Topography and Landmarks of the Last Hundred Years,”4

remarks that although all the buildings on Beacon Hill, including those on Park

Street, are comparatively modern, there exists abundant material wherewith

sketches may be drawn of famous buildings in that region, and of the people who

have lived in them. Here resided many men and women who have been leaders in

the social and literary life of the City. Here too lived numbers of the

prominent merchants, lawyers, and men of affairs, who were active in promoting

the welfare and development of the community.

The

vicissitudes of Boston’s winter climate are

well known. In the mild winter of 1843, according to a recent statement

by the

editor of the “Nomad’s” column in the

“Transcript,” “ground-hogs were rampant

all over Beacon Hill and the Common; not having denned up at all; and

the only

snow of that year was in June.” Whereas on New

Year’s Day, 1864, milk froze in

its pitchers on breakfast-tables, and thermometers in the vicinity of

Park

Street Corner registered sensational figures below zero!

1 First Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston.

2 The

Bostonian Society Publications, III. 1919.

3 Samuel

Barker, Boston Common.

4 The

Memorial History of Boston.