| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

XV

TEA-HOUSES AND TEMPLES Tea-houses and temples run together very easily in the Japanese mind, for wherever you find a temple there you also find a tea-house. But tea-houses are not confined to the neighbourhood of temples: they are everywhere. The tea-house is the house of public entertainment in Japan, and varies from the tiny cabin with straw roof, a building which is filled by half a dozen coolies drinking their tea, to large and beautiful structures, with floors and ceilings of polished woods, splendid mats, and tables of ebony and gold. The tea-house does not sell tea alone. It will lodge you and find you dinners and suppers, and is in country places the Japanese hotel. If tea-houses sold tea and nothing else it is certain that European travellers would be in a very bad way, for there is one point they are all agreed upon, and that is that the tea, as a rule, is quite unpalatable to a Western taste. However, it does not matter in the least whether you drink it or not as long as you pay your money, and the last is no great tax--about three halfpence. When a traveller steps into a tea-house the girl attendants, the moosmes, gay in their scarlet petticoats, kneel before him, and, if it is an out-of-the-way place, where the old fashions are kept up, place their foreheads on the matting. Then away they run to fetch the tea. Japanese servants always run when they wish to show respect; to walk would look careless and disrespectful in their eyes. The tea arrives in a small pot on a lacquer tray, with five tiny teacups without handles round the pot. There is no milk or sugar, and the tea is usually a straw-coloured, bitter liquid, very unpleasant to a European taste. But if a cup be raised to the lips and set down, and three sen--a sen is about a halfpenny--laid on the tray, all goes well, and every one is satisfied. This bringing of tea to a visitor is universal in Japan. It is not only done in a tea-house, where one would expect it, but on every occasion. A friendly call at a private house produces the teacups like magic, and when a customer enters a good shop, business matters are undreamed of until many little cups of tea have been produced; and if the customer has many things to buy and stays a long time, tea is steadily brought forward in relays. If you don't care for your tea plain, you may have it flavoured with salted cherry blossoms, but that is not considered an improvement by the Westerner, who longs for sugar and milk. If you wish to stay for the night at a tea-house, a room is made for you by sliding some paper screens into the wall and ceiling grooves, and a couple of quilts are laid on the floor to form a bed. That is the whole provision made in the way of furniture if you are off the beaten track of tourists: the rest you must provide for yourself. In the cities the tea-houses of the grander sort are the scenes of splendid entertainments. When a Japanese wishes to give a dinner to his friends he does not ask them to his house; he invites them to a banquet at some famous tea-house. There he provides not only the delicacies which make up a Japanese dinner, but hires dancing girls, called geisha, to amuse the company by their dancing and singing. A foreigner who is asked to one of these Japanese dinners finds everything very strange and not a little difficult. At the doors of the tea-house his boots are taken off, and he marches across the matting, to do his best to sit on his heels for a few hours. This gives him the cramp, and soon he is reduced to sitting with his back against the wall and his legs stretched out before him. He can manage in this way pretty fairly. There may be a table before him, or there may not. If there is a table, it will be a tiny affair about a foot high. There will be no tablecloth, no glasses, no knives and forks, no spoons, and no napkin. He will be expected to deal with his food with a pair of chopsticks. When these are set before him, he will see that the two round slips of wood are still joined together. This is to show that they have never been used before. He breaks them apart, and wonders how he is going to get his food into his mouth with two pencils of wood.

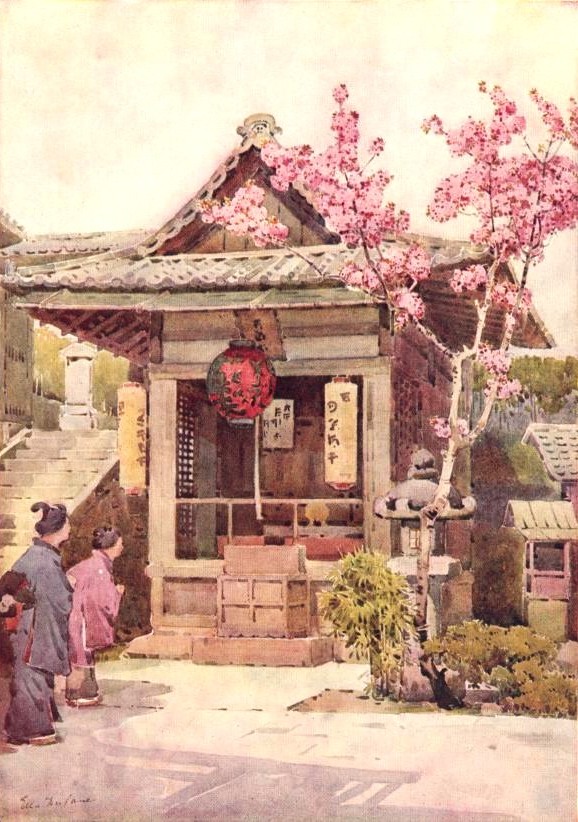

A BUDDHIST SHRINE The feast begins with tea served by moosmes, who kneel before each guest. Each wears her most beautiful dress, and is girded with a huge and brilliant sash. After the tea they bring in pretty little white cakes made of bean flour and sugar, and flavoured with honey. The next course is contained in a batch of little dishes, two or three of which are placed before each guest. These contain minced dried fish, sea slugs floating in an evil-smelling sauce, and boiled lotus-seeds. To wash down these dainties a porcelain bottle of saké, rice-beer, is provided. The unhappy foreigner tastes one dish after the other, finds each one worse than the last, and concludes to wait till the next course. This is composed of a very great dainty, raw, live fish, which one dips in sauce before devouring. Then comes rice, and the chopsticks of the Japanese feasters go to work in marvellous fashion. With their strips of wood or ivory they whip the rice grain into their mouths with wonderful speed and dexterity, but our unlucky foreigner gets one grain into his mouth in five minutes, and is reduced to beg for a spoon. The next course is of fish soup and boiled fish, and potatoes appear with the fish; but, alas! the fish is most oddly flavoured and the potatoes are sweet; they have been beaten up with sugar into a sort of stiff syrup. Next comes seaweed soup and the coarse evil-smelling daikon radish, served with various pickles and sauces. Among the other oddments is a dish of nice-looking plums. Our foreigner seizes one and pops it in his mouth. He would be only too glad to pop it out again if he could, for the plum has been soaked in brine, and tastes like a very salty form of pickle. As he experiments here and there among the wilderness of little lacquer bowls which come forth relay upon relay, he feels inclined to paraphrase the cry of the Ancient Mariner, and murmur: "Victuals, victuals everywhere, and not a scrap to eat!" When at length the dinner has run its course the geisha, in their beautiful robes of silk and brocade and their splendid sashes, come in to sing and dance. Europeans are soon tired of both performances. The geisha, with her face whitened with powder, and her lips painted a bright red, and her elaborately-dressed hair full of ornaments, sits down to a sort of guitar called a samisen and sings, but her song has no music in it. It is a kind of long-drawn wail, very monotonous and tuneless to European ears. The dancing is a kind of acting in dumb show, and consists of a number of postures, while the movements of the fan take a large share in conveying the dancer's meaning. When our foreigner starts home from this long and rather fatiguing entertainment, he finds that he has by no means finished with his dinner. On his way to his carriage he will be waylaid by the little moosmes who have waited upon him, and their arms will be filled with flat white wooden boxes. These contain the food that was offered to him and left uneaten, and Japanese etiquette demands that he shall take home with him his share of the scraps of the banquet. |