| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

PART II

IN THE MOUNTAINS "And daily how through hardy

enterprise

SPENSER

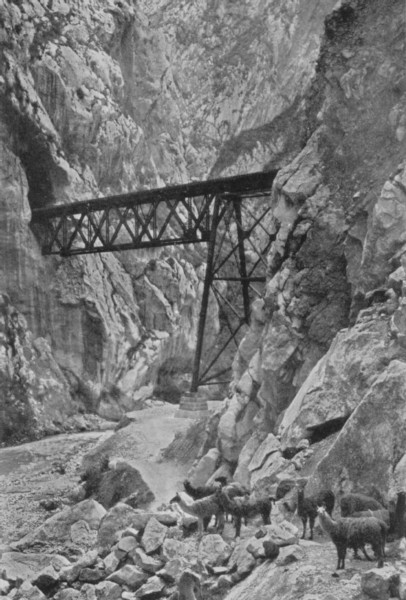

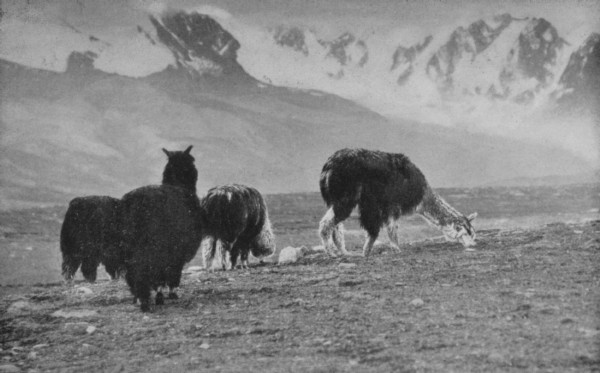

Many great regions are discovered, Which to late age were never mentioned, Who ever heard of th' Indian Peru? Or who in venturous vessels measured The Amazon huge river, now found true? • • • • • • • Why then should witless man so much misween That nothing is, but that which he bath seen?" CHAPTER I THE HIGH REGIONS I No Peruvian thinks of zones differing from his own as being remote geographical localities. Peru contains them all. He does not have to travel over the face of the earth for a change of climate, but makes short, domestic, vertical journeys instead. Living under his banana groves among his sugar-fields in the lush coast valley, if he feels need of fresher air, he takes a trip up to the temperate zone, where apple orchards and wheat-fields lie spread out in a recess of the mountains, and strawberries redden to perfection. Has he curiosity to see an arctic storm, he goes a little higher, coming out upon the bitter table-land where crests of glaciers cut the sky. The Andes, youngest of mountains — what a weirdly tossed world! All the most obscure and harsh substances of the planet have been heaped up here. The rough places of earth have turned over and reached up where they brush against the firmament. Volcanic power has its domain in these high regions of earth, where nature is in anarchy, possessed of unnatural powers. It is a great, uneasy wilderness, where torrents rattle through daring gorges, only to fall a thousand feet, scattering into a dust of foam. Icicles hang from every joint between the stones. It is a colossal, brutal land, fresh from the cataclysm, whose ponderous masses of rock are all sterile from cold, all silent under perpetual snow. In its clearness of atmosphere sparkles a new conception of the night-time sky. It is a land where thin layers of lichens are the only trace of plant life, where condors wheel about the highest pinnacles, and silver lies buried deep in the ground. It is the lair of mercury-mines which paralyze those working in them, where hot and cold fountains mingle to make one river, where springs of tar and rivers of peat ooze from suffocation within.  A Trestle of the Highest Railway in the World, across the Infiernillo Hot from their passage through the glowing veins of the mountains, springs bubble into life, sour, turbid, saturated with gases, possessed of weird powers, capable of giving life as well as of taking it away. Their waters turn to stone as they spread over the plain. In this frozen waste of glaciers, sheltering fire and magnetic iron within, all forces and elements are seething, though shrouded with snow. As the noise of water fills the desert, so the roar of fire can be heard among the frozen mountain-tops. Long, long ago, a volcano was puffing out asphyxiating fumes. It melted the metal on the edge of its crater, and turned rocks burst from its own black mouth-pit to red and yellow and green. Fire boiled over the edge and advanced in a tide of flame down the mountainside and into the valleys. The favorites of the Sun who lived beside it complained to him of the ruin caused by the volcano. Somewhat irritated himself, he "smothered the genius of devastation in his lair," covering the top of the mountain with an impenetrable cap of snow, leaving little, seraphic blue lakes here and there upon it as a hostage. This frozen giant, whose entrails the fire is devouring, still lies sleeping with his granite dreams. When all the beneficent qualities inherent in a world have been wrested from it, and life has disappeared toward experiences elsewhere, or when a comet's tail has swished life suddenly away, a wilderness like that of the high Andes would result — a place where chaos and disorder is the only rule. Yet the law of chaos we must believe is no law at all. Stretched among these mountains is the vast table-land called puna, on which flourished the Indian civilizations so famous in history. Abundant rain falls, but cold prevents it from covering the ground with flowers. Reveling in the high pressure of the mountain-tops, hummingbirds flit about in the snow. The finest morning begets the heaviest afternoon clouds, and warm atmospheric currents, quite definitely confined in the cold air, travel through the desolation. The wind, seeming to tear up the ground and pulverize the summits, is unable to dissipate a mist which magnifies the rocks and presents the traveler's giant shadow with a whole system of concentric rainbow halos — his apotheosis in the clouds. The wind brings with it cold clouds of dust laid only by a fresh fall of snow. It mummifies the beasts of burden which fall by the way. Mirages, too, the escort of tropical heat, shimmer upon these arctic plains. With all the paraphernalia of the torrid zone, limitless vagaries of torrid force which knows no law of custom, the puna has no enjoyment of it. For the cold seems also to have taken on the exuberance of tropical nature. You may lose your way in a snow-storm; or in the hot and stifling valleys, where the tropical sun can concentrate, you may die of the bite of a venomous serpent. Parched by fever-thirst, you may not drink the water, for it brings varieties of diseases, bounded by their valleys' walls. Your mule may sink into a morass or break his leg in a viscacha burrow. He may eat a poisonous mala yerba or garbanzillos. Broadly laden, he may be scraped off a bridle-path clinging to the sheer precipice. He may be carried away by the swift current of a glacier stream in attempting to ford it. He may collapse from lark of air and leave you stranded in a lifeless desert. Soroche-sick and burned to a crisp by the relentless cold, you urge on the staggering mule as he stops constantly to gulp the thin air. He cannot be satisfied, although he has a second set of nostrils cut through to ease his breathing and avert soroche. Still the glaciers crawl down from brooding peaks above. The sun, magician of the bleak mountain regions, comes out and glints green on broken strata of the red mountains. It discovers all the bright colors in the hills of porphyry and clothes them with fresh shadows. It runs along a vein of shining mica to accuse it. It plunges into the middle of a lake of polished jet settled in the snow, "making a great, golden hole." A single hill in sunlight glows with streaks of iris-color, matching the rainbow forms as they appear above and fade again. Little cloud islets surround far-off peaks, sunk beneath the horizon. Pyramids of ice twinkle, and fantastic stone needles stand in rows too precipitous for snow to cling to their bare sides. They are called early inhabitants, which Pachacamac in his anger turned to stone. The air, though thin almost to disappearance, cuts like a razor-edge. With eyelashes frozen together, you can yet be sun-struck. Teeth to teeth, cold and heat meet upon "the waste, chaotic battlefield of Frost and Fire." Cold is besieged in vain by the sun at its hottest. This land of silent chaos takes on the cold of outer space so near by, which, shot through by the fierce heat of the sun, is incapable of absorbing any warmth. The magical sun, dispelling somewhat the mountain-sickness, only brings with it another, even worse. For blazing across the snow-fields in its tropical fury, surumpe follows, snow-blindness, cured only by fresh vicuna flesh laid upon the eyes, so the Indians say. The over-arching vault is indigo. Desolation is brightened by a radiant light, infinitely attenuated, "diaphanous as the starry void." It caresses the bristling scenery. It penetrates caverns and fills them with a gold and purple mist. In the world of light and shade which it creates, even the shade gives light. Upon water, the light, startled by its own reflection, sparkles and dances and leaps. Words give no idea of the brilliancy of the snow on the crests of the Andes, because there are no words made of sunlight and crystals: luminous, empyreal snowshine, shattered by the sun now and then into rainbow colors. As silence is perfect only because it has the possibility of being broken at any instant by a gigantic crash, so whiteness is the emblem of perfect purity only because the possibility of all color lies within. He who has not galloped across an Andean puna chased by a tempest, has not known the full, wild force of the elements. Lost in a whirl of lightning, wind, and snow, his mule, maddened by electricity snapping off the ends of his ears, dashes from the thunder chasing at arms' length. Red lightning zigzags between the summits. Blood-red cataracts tumble over the volcanic crags. Huge pieces of rock break loose and crash from the cliffs. Deep furrows are ripped up, following the lightning as it runs along close to the ground. Lack of air and bitter cold are forgotten. Each flash acts like a fresh whip-sting to the mule. The compass snaps against its box. Magnetic sand leaps into the air and flies about in sheets. The rocks seem ablaze, the whole sky is on fire. The atmosphere quivers with uninterrupted peals, smothered in the gorges of granite, buffeted by the mountainsides, torn apart by the high peaks, till, finally overtaking each other, they are confounded in a mighty burst of thunder that breaks loose in the sky, and in a cosmic roar reverberates against the nothingness of outer space. Then the sun slowly settles in calm. The striped walls flare in the sunset light, flamboyant as the bang of brass mortars in pagan idolatry. The mountains shine from base to summit, while "the night, grazing the soil and step by step raising its wide flight, — the dying light, fleeing from crest to crest, makes the most sublime summit resplendent, until the shadow covers all with its wing." All vague sounds subside into an "excess of silence." The last incandescent peak shines, and goes out. II

How appropriate it is that quicksilver, a liquid heaviest of metals, should come from this land of contrast. The most elusive product of a mysterious country, imperceptibly by fumes it enters the nostrils of those who seek it, either destroying their teeth or disintegrating their limbs; a metal which, becoming mere vapor, is again transformed by a sudden chill to metal; though it rises as steam, it falls as quicksilver. Pliny calls it the poison of all things, the "eternal sweat," since nothing can consume it. To the Incas it remained a mystery, for although its "quick and lively motions" were admired, its search, being harmful to the seeker, was forbidden. They did, however, use the vermilion found with it: handsome women streaked their temples with vermilion. Silver also is born in certain cold and solitary deserts of the mountain-tops, melted by subterranean fires within its deep veins. Silver being the only produce of the soil, the necessities of life have to be brought from afar. It seems as if the vigor that vegetation would absorb goes into the silver. The mountain-tops are full of legends of mine discoveries usually intertwined with romance. Greedy lovers have sacrificed their love for a mine, and many are the mines filled with revengeful floods. Huira Capcha, a shepherd who had been guarding his flocks near Cerro de Pasco, awoke one day to find the stone beneath the ashes of his fire turned to silver. It is told in connection with the mine of Huancayo that an Indian friend gave a Franciscan monk a bag of silver ore. The eager friar wished to know where more could be found. The Indian consented to show him, but blindfolded the friar, who took the precaution to drop a bead of his rosary here and there as he went along. When at last the monk stood marveling at the bright masses of silver, his Indian friend gave him a handful of unstrung beads. "Father," he said, "you dropped your rosary on the way!" In 1545, an Indian called Hualpa was pursuing a vicuna up the mountainside. He grasped at the bushes as he scrambled up a steep cliff. One came up by the roots, which were hung with globules of silver. That particular vicuna hunt took place on a mountain called Potosi. The discoverer of the mine of Potosi was murdered by a Spaniard named Villarroel, who became its proprietor. The murder was an unnecessary precaution, however, since a mysterious voice had commanded the Indians to take no silver from this hill, which was destined for other owners. From that romantic mountain has flowed far "more silver than from all the mines of Mexico." "Prior to 1593 the royal fifth had been paid on three hundred and ninety-six millions of silver." The only difficulty the Spaniards encountered was in finding water enough to wash the silver. The hills about Potosi gleamed with as many as six thousand little fires, smelting furnaces belching horrid odors, scattering liquid silver pellets. They had to be carried where the wind blew, sometimes higher up and sometimes lower down. So this splendid Imperial City grew up in the subtle air, varied by icy winds and storm. The extraction of its prodigious wealth was a means of torture to those who worked in continual darkness without knowledge of day or night. Yet, even among the tops of the Andes, living things are adjusted to their environment, queer little animals of the heights giving the only human atmosphere there is. Leaping viscachas, with cat-like tails, carve through the frozen ground village burrows made to last forever, treacherous pitfalls for a traveler's mule. With the finest, silkiest fur, valued by even the Incas, chinchillas sit in the shadows, never in the sun. They appear suddenly on the steep cliffs at dusk and nibble stiff grasses; then disappear like magic, leaving little chains of footprints in the snow. A small toad inhabits the boundaries of perpetual snow, and a nice little plant called maca has its best flavor only above an altitude of thirteen thousand feet, where all flavoring ingredients have long been left behind. The wild gazelle of the Andes, with fur the color of dried roses, the graceful vicuna, creature of quickness and flight, lives upon the coldest heaths and in the most secluded fastnesses of the mighty Andes and seldom descends below the limit of perpetual snow. His back, burned tawny by the tropical sun, is covered with snow. Far in the distance a flock is grazing. The single male stands near by upon a rock. A foreign sight or sound, a quick movement of his foot, a short, shrill whistle vibrating through the clear, puna air, a flash of golden brown, and the whole flock is lost in the wilderness of rocks, fleeing miles without stopping. It is said that if the male is wounded, the females surround him, allowing themselves to be shot down rather than leave. The vicuna defies pursuit or capture and disappears at the first glimpse of intruders, driving the young before him. He is no less wild than in the days when he was royal purveyor of softest fabric to the Incas' wardrobes. His habits are as elusive now as then, when Indians thirty thousand strong entrapped the wild animals among the mountain-tops. These solemn huntings took place every fourth year. Meanwhile the wise men kept account of the flocks with colored threads, so-called quipus, their method of enumeration.  Alpacas on the Andean Puna Cousins of the vicuna are the awkward huanacus, which drink brackish water as gladly as fresh and seek a favorite valley where they may breathe their last and pile up their accumulated bones — as sea-lions go to particular islands to die, the wounded being helped thither by companions. The Incas worshipped the llama, alpaca, and these wild relatives of theirs; they carved their grotesque forms in stone and fashioned their likeness in gold and silver for household gods. Far above the limit of human life, even beyond the haunts of vicunas, there is still one living creature. His shadow sweeps over the wilderness as he passes between it and the sun — a shadow the only appearance of life. It is the condor, who lays her white eggs on the bare rock of the loftiest mountain peaks and knows where the heart of each animal lies. The mighty condor, who can kill an ox with his beak of steel, who can swallow a sheep or exist a month without food. The majestic condor, who swims in the highest air or sweeps down upon his prey with a deafening whir of wings. The condor, a symbol of light, who circles up to the ether of outer space on an almost imperceptible, tremulous motion, or proceeds undisturbed, without effort or flutter of wings, in the icy teeth of a tempest, a symbol of storm. He watches the sun rise over a continent-jungle, glimmering with heat and dampness, and long after the sunset glow has faded from the highest snowy peak, he sees its fiery ball drop beyond the farthest edge of the Pacific. The fabulous condor, known in Europe when Peru was a myth, a hostage from a fairyland of gold and silver; a griffin which revels in solitude and in evidences of things gone by. Loneliness is the condor's only friend. The wind howls through his broadened wings. |