| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER IV

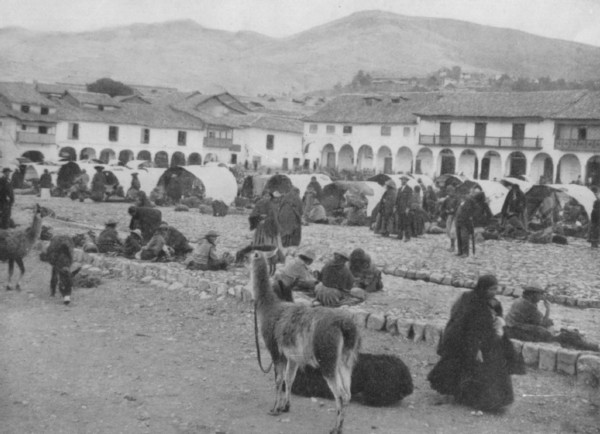

THE INCA AND HIS EMPIRE No one dared to look upon the Inca, as he radiated the light of his divine Sun-father. He lived and ruled as a deity, representative of God, supreme arbiter of all creatures breathing the air or living in the water. "The very birds will suspend their flight if I command it," Atahualpa once said. His person being holy, his body after death, preserved in its living likeness, was still worshipped. Carried about on a golden litter, the Prince Powerful in Riches moved from palace to palace, and his feet never touched any but sacred ground, consecrated by his contact, if not previously hallowed. To carry his person was so singular an honor that his weight was not a burden, as cultivating his fields was a labor performed with hymns of joy. This Sun of Cheerfulness passed beneath flower-covered arches, while his bearers crushed out sweet odors from flowers beneath their feet. Indeed, "the shouts of the multitude as he passed along caused the birds flying over to fall to the ground!" If these "facts" seem more like romance than truth, they have at least masqueraded under the guise of history for more than three hundred years. The Inca was clothed in garments made of the silky hair of the vicuña, which lives above the line of perpetual snow. Woven as they were to be worn, from threads of invisible fineness, the soft garments were made by cloistered Virgins of the Sun. They were enriched with bits of gold, silver, emeralds, a fringe of gorgeous feathers, and with mother-of-pearl. Pearls were not used, as their "search endangered the lives of the seekers." The Inca wore a suit but twice, then conferring it upon some person of royal blood. These were the garments taken as sumptuous gifts to the monarchs of Spain. Many were the Incas' marks of distinction. Their heads were shorn, all but one lock, as Manco Ccapac had ordained. The "shearing" was done by means of a sharp flint. Another distinction was enlarging the velvet of the ear by inserting ornaments, so that it reached the shoulder, suggesting the Spanish title, Orejones. The peculiar badge of the Inca was a fringe encircling his brow, called the llautu, "the mark whereby he took possession of the realm, a red roll of wool more fine than silk, which hung in the midst of his forehead." And his chief distinction, worn in his colored wreath and pointing upward, were the two long pinions of the corequenque, that mysterious pair of birds which, isolated in a snowy desert beside a little lake, lived at the foot of an inaccessible mountain. Though there are other snowy deserts and other little lakes and other inaccessible mountains, no similar pair of birds could ever be found. In fact, there never were but two alive at the same time — symbol of the two original parents. They recall the screaming oo, a blackbird of the Hawaiian Islands, famed for concealing under each wing a single yellow feather, used in making those magical feather cloaks for the kings on ceremonial occasions. Each Inca must have new pinions, as each must have his new palace, for the apartments of a dead sovereign were closed at death; his golden utensils, jewels, and treasure were buried with him. Men and women, practised in the art of lamentation, cried for one year after his death, when his account was closed. Then the heir "bound his head with the colored wreath" and started forth through his dominions. With the rainbow as their emblem, even Inca facts had distinctive colors and were interwoven with facts of other colors, ideas being expressed directly without the technique of words. Knots in a parti-colored twist were their hieroglyphics, the famous quipus, and the Officers of the Knots were their historians. They intertwined the bright filaments of different sizes as well as colors, and tied into remembrance everything from laws and army supplies to ballads of the poets, sung on days of triumph. Such a Sovereign-deity as the Inca could force the equality of all his people, commanding them to be happy. Here was a whole nation moved by sameness of will — desire to please their sovereign. Observance of law was natural to these industrious subjects, who were treated with absolute justice by an absolute despot. Each was just as well fed, just as well clothed, just as well housed, just as well amused, as his neighbor. Emissaries from the king inspected his neighbor to see that it should remain so. All persons had to allow messengers from the Inca to inspect what they were doing at any time. Such as were found commendable were praised in public. Such as were idle and slovenly were scourged on the arms and legs. One punishment was whipping by a deformed Indian with a lash of nettles. "There never could be any scarcity or famine, for, if a man failed to take his turn at the water for irrigation, he received publicly three or four thumps on the back with a stone... shamed with the disgraceful term of... mizqui tullu, being a word compounded of mizqui, which signifies sweet, and tullu, which is bones."  Indian Water Carrier, Sicuani As labor was the only tribute, the rich were not taxed more than the poor. The blind were required to cleanse cotton of seeds and rub maize from the ears. "The old men and women were set to affright away the birds from the corn, and thereby gained their bread and clothing." No one, however impotent, could escape tribute. The poorest gave lice, "making themselves clean and not void of employment in so doing." Who, indeed, were the poor? Those who were incapable of work, who had to be fed and clothed out of the king's store. "There were no particular tradesmen... but every one learned what was needful for their persons and houses and provided for themselves." Laws would hardly seem necessary to control so exemplary a nation. Here, however, are a few paternal laws, thought necessary by the Lover of the Poor: against the adornment of clothing with gold and silver and jewels; against profuseness in banquet and delicacies in diet; against the ill manners of children; of good husbandry and hospitality; providing a new division of lands every year, according to the increase and diminution of families; punishing those who destroyed landmarks or turned the water aside; devoting the services of all master workmen to the Inca, and supplying them with gold and silver and other materials for the exercise of their ingenuity. Since the Sun-god, or the Inca, had benignly bestowed them for the people's good, laws received the same veneration as the precepts of religion, from which no subject of the Incas could dissociate them. A breaker of the law was guilty of sacrilege, and no punishment could be too severe. In fact, most crimes were punishable by death. The sinner was thrown over a precipice or into a ditch of serpents, jaguars, and pumas. The worst sin of all, high treason, exacted in expiation not only the death of the sinner, but that of his family, even of his neighbors. His very trees were pulled up by the roots, and his fields sown with salt. "But as there was never any such offense committed, so there was never any such severity executed," a mitigating remark of Garcilasso in connection with a certain crime. The basis of the Inca government was tribute, personal labor given to the Sun and to the Inca, a source of continual delight, a supreme privilege. So the Sun, or his representative the Inca, was furnished by his people with food, tilled by them from his own ground; clothing for his soldiers or his needy from the wool of his own flocks; bows and arrows, lances and clubs, ropes for carrying burdens, helmets and targets each where most easily procurable. Temples and palaces of the Inca, his aqueducts, roads, and bridges were built with hymns of rejoicing. The laborers never got out of breath so as to spoil the cadence of the hymn of triumph; the chroniclers fail to say whether in obedience to law or from a sense of good taste. In addition, all the provinces paid tribute of the most beautiful women, who were kept in convents as wives of the Inca; and he might choose any who suited him. The great maxim of the Incas was increase of empire, their plea being the best interest of the tribes they were to conquer. The Inca sent word that he would come "not to take away their lives or estates, but to confer upon them all those benefits which the Sun, his father, had commanded him to perform toward the Indians. He (would come) to do them good, by teaching them to live according to rules of reason and laws of nature, and that, leaving their idols, they should henceforward adore the Sun for their only god, by whose gracious command he had received them to pardon. To which end, and to no other purpose (for he stood in no need of their service) he traveled from country to country." So well did most of the surrounding tribes realize this, that messages of submission came before the conquerors had even turned in their direction. If it happened that because of ignorance they held out against the benefits an indulgent sovereign was waiting to bestow, the Inca's messengers informed them of his exact intentions. All good gifts would be theirs, provided only they would renounce their independence, their language and religion, and send their chief god as an hostage of submission to the Temple of the Sun in Cuzco. Honored servants of the Inca would come to them in return to acquaint them more in particular with the new benefits they were about to receive. Skilled workmen would teach them the arts. The sons of their cacique (chieftain) would be sent to Cuzco to receive instruction. Moreover, the Inca would confer upon them the garments worn by his own gracious person. Nearly all perceived the wisdom of such a course at once. But if in blindness any still rebelled, messengers brought word that "the Inca pitied their folly which had so unnecessarily betrayed them to the last extremity of want and famine." For enlightened they were to be, in spite of themselves. Wonderful are the tales of these victorious campaigns, for the Inca's army never knew defeat. The soldiers were as plentifully supplied from vast granaries as if in Cuzco. If the march led through lowlands, the entire army was relieved every two months. Though the Indians of the mountain-tops did not object to cold, they succumbed to fevers soon after descending into the comfortable valleys. When a new province had been incorporated, the gracious Inca "confirmed the right of possession to the natives of it." The empire extended from the Chibchas and Caras of Ecuador, beyond the Chilean deserts. Only one region dared defiance; that was the primeval jungle. The armies might skirmish about upon its edges, and exact exotic tribute of the savages who ventured forth. But within its grim interior they were secure. In the provinces of Antis, people "killed one another as they casually met," and worshipped a jaguar, the original lord of the jungle. They sacrificed hearts and blood of men to huge snakes "thicker than a man's thigh." They made war only to eat the flesh of their enemies. They were called "nose of iron" because they bored the bridge between the nostrils to hang in it a jewel or long piece of gold or silver. With a handful of men, Yupanqui visited these savages below the Andes and imposed worship of the Sun. With a handful of men, the Spaniards wiped the great organization of the Empire of the Sun off the face of the earth and established upon its ruins a Christian civilization. The people in the Valley of Palta bound tablets upon the head of a new-born child and tightened them each day for three years, until the skull was elongated, in order to fit the pointed woolen cap which it was the fashion to wear. The Chachapoyas wore a black binder about their heads, stitched with white flies, and instead of a feather, the tip of a deer's horn. Their chief weapons were slings bound about their heads, and they adored the condor as their principal god. The Chancas were the most dangerous opponents of Cuzco, a powerful race owing their origin to a jaguar, who dressed in skins of their god and carried effigies of jaguars with a man's head to their sacrifices of children, by whose eyes they prognosticated. The caciques of all dependent tribes were obliged to appear once a year at court, or if they lived very far away, once in two years. They brought with them gold and silver from their mines, for all such things were devoted to worship of the Inca. Failing these, they presented jaguars, droll monkeys, parrots, wondrous condors, and giant toads and snakes that were very fierce, kept in dens for the grandeur of the court. People from all climates presented indigenous gifts, the most beautiful or the most curious of any creature or plant within their domains. Any known thing preeminent in any way added the name of its peculiar excellence to the titles of the Inca. His court in Cuzco consisted of more than eight thousand persons, nobles who traced descent from the Sun, and representatives of all the fantastic tribes blest by the Inca's clemency. Even the greatest lords carried bundles in his presence. The noble city of Cuzco, where the children of Inti first stopped with their wedge of gold, was itself worshipped. Those who lived in Cuzco had a certain superiority. Divisions of the city were the Terrace of Flowers, the Lion Picket with the dens of pumas, the Field of Speech, the Quarter of the Great Serpents, the Scarlet Cantut — the flower of the Inca — the Holy Gate, the Shoulder Blade, the Seaweed Bridge, and so on, bounded by small streams and long, somber walls of perfectly fitted stones. Up above the city hangs the stupendous fortress of Sachsahuaman, exceeding all the seven wonders of the world, a cyclopean work of the primitive age. Squier says: "The largest stone in the fortress has a computed weight of 361 tons." Sachsahuaman must indeed have been raised by enchantment in a night like Tiahuanacu, for it surpasses the art of man, the labyrinth of passageways contracting here and there so that a single man could keep back an army, subterranean tunnels leading to temples and palaces of the city. From the inmost recesses of the fortress, a fountain of clear water bubbles. Its mysterious murmur fills the secret passageways.  In the Market, Plaza Principal, Cuzco Even a single stone destined as a part of the fortress partakes of the enchantment. According to legend, twenty thousand Indians had dragged it from a distant quarry, up and down over the wild mountains. Once it fell, killing " three or four thousand of those Indians who were the guides to direct and support it." And when, after its painful journey, the monster finally beheld the lofty fortress of which it was to form a part, it fell for the last time, shedding bloody tears from the hollow orbs of its eyes. It still lies on the same spot, receding deeper and deeper into the ground whenever attempts are made to remove it. |