| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

CHAPTER VI

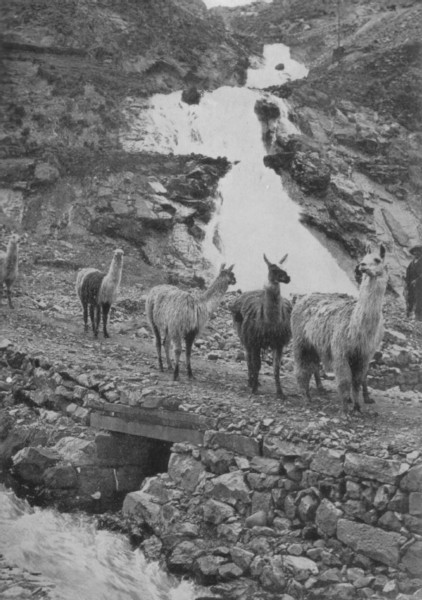

INDIANS AND LLAMAS HAD the Indians of the sixteenth century not known that their overthrow was the will of Pachacamac, the miracles constantly favoring the Spaniards would have forced them to recognize the fact. Pious chroniclers tell of Saint James on a white horse, who came with glistening sword to turn the tide of battle, and of the Virgin Mary, whose appearance in the clouds blinded the hostile Indians. The Incas could but succumb to the sovereign will. Some retreated beyond the mountains, leaving indelible traces upon the people of the jungle. Some were thrown into fortresses, which "their ancestors had built for ostentation of their glory." On the authority of Garcilasso, thirty-six males of the blood of the Sun, who had been condemned to live in Lima, the Spanish City of the Kings, had in three years' time all died. Sayri Tupac, a nephew of Atahualpa, had come to Lima for the privilege of renouncing his sovereignty. The amautas had consulted the flight of birds as to whether he should surrender himself to the Spaniards, but as Garcilasso says: "They made no inquiries of the devil because all the oracles of that country became dumb so soon as the sacraments of our holy mother, the church of Rome, entered into those dominions." "Ah!" said Sayri Tupac, as he lifted the gold fringe of the table-cloth, "all this cloth and its fringe were mine, and now they give me a thread of it for my sustenance and that of all my house." He was allowed to withdraw to the beautiful valley of Yucay, "rather to enjoy the air and delights of the pleasant garden formerly belonging to his ancestors than in regard to any claim or propriety he had therein." But he sank into a deep melancholy and died within two years. The Spaniards were occupied with duels and assassinations of friends, bloody civil wars and religious disputes, usually about the Immaculate Conception. One can read volumes of such proceedings. Indian revolts were a constant interruption. The Spaniards gradually discovered that it was impossible to keep the Indians quiet while an Inca remained alive; so in 1571, less than forty years after their arrival, Tupac Amaru, the last of the Incas, was put to death by the Spaniards in the following manner, as described by Garcilasso de la Vega in the words of his first English translation (1688). "His crimes were published by the common crier, namely, that he intended to rebel, that he had drawn into the plot with him several Indians who were his creatures,... designing thereby to deprive and dispossess his Catholic majesty, King Philip the Second, who was emperor of the new world, of his crown and dignity within the kingdom of Peru. This sentence to have his head cut off was signified to the poor Inca without telling him the reasons or causes of it, to which he innocently made answer that he knew no fault he was guilty of which could merit death, but in case the vice-king had any jealousy of him or his people he might easily secure himself from those fears by sending him under a secure guard into Spain, where he should be very glad to kiss the hands of Don Philip, his lord and master. He farther argued that... if his father with two hundred thousand soldiers could not overcome two hundred Spaniards whom they had besieged within the city of Cuzco, how then could it be imagined that he could think to rebel with the small number against such multitudes of Christians who were now disbursed over all parts of the Empire." How little effect the words of Tupac Amaru produced upon the Spaniards can be judged by the following: "Accordingly the poor Prince was brought out of the prison and mounted on a mule with his hands tied and a halter about his neck with a crier before him declaring that he was a rebel and a traitor against the crown of his Catholic majesty. The Prince not understanding the Spanish language asked of one of the friars who went with him what it was that the crier said, and when it was told him that he proclaimed him a traitor against the king, his lord, he caused the crier to be called to him and desired him to forbear to publish such horrible lies, which he knew to be so, for that he never committed any act of treason nor ever had it in his imaginations, as the world very well knew. 'But,' said he, tell them that they kill me without other cause, that only the vice-king will have it so, and I call God the Pachacamac of all to witness that what I say is nothing but the truth.' After which the officers of justice proceeded to the place of execution.... The crowds cried out with loud exclamation accompanied with a flood of tears, saying, Wherefore, Inca, do they carry thee to have thy head cut off?... Desire the executioner to put us to death together with thee who are thine by blood and nature and should be much more contented and happy to accompany thee into the other world than to live here slaves and servants to thy murderers.' "The noise and outcry was so great that it was feared lest some insurrection and outrage should ensue amongst such a multitude of people gathered together, which could not be counted for less than three hundred thousand souls. This combustion caused the officers to hasten their way unto the scaffold, where being come the Prince walked up the stairs with the friars who assisted at his death and followed by the executioner with his broad sword drawn in his hand. And now the Indians feeling their Prince just upon the brink of death lamented with such groans and outcries as rent the air.... Wherefore the priests who were discoursing with the Prince desired him that he would command the people to be silent, whereupon the Inca, lifting up his right hand with the palm of his hand open, pointed it towards the place whence the noise came and then lowered it by little and little until it came to rest upon his right thigh, which, when the Indians observed, their murmur calmed and so great a silence ensued as if there had not been one soul alive within the whole city. The Spaniards and the vice-king who were then at a window... wondered much to see the obedience which the Indians in all their passion showed to their dying Inca, who received the stroke of death with that undaunted courage as the Incas and the Indian nobles did usually show when they fell into the hands of their enemy and were cruelly treated and unhumanly butchered."  An Indian Pastoral When they first stepped upon the shores of Peru, a Spaniard or two could travel hundreds of leagues alone through this foreign country on the shoulders of men and be adored as gods in passing. Before long, an army was not secure. A Spanish governor and his escort of thirty men were resting one day upon a high plain. The Indians, whistling to each other with bird calls and barking like wolves in the night, "went softly to the Spaniards' tents, where, finding them asleep, they cut the throats of every one of them." Such deeds were being done in the Empire of the Lover of the Poor, the Deliverer of the Distressed, where formerly each individual had been forbidden to injure even himself. The spirit of rebellion spread among the Indians. They tried to poison the water-supply of the City of the Kings. They tried to burn Cuzco, imagining they could burn the Spaniards with it. Their revolts culminated in that great rebellion of 1780 under Jose Gabriel Condorcanqui, called Tupac Amaru, whose descendant, through a daughter, he was. His followers swore their hatred of the white race and vowed not to leave a white dog, not even a white fowl alive. They even scraped the whitewash from the walls of their houses. They did succeed in strangling a governor. In return, Tupac Amaru's tongue was cut out, and after seeing his wife, son, and brother tortured to death before his eyes, was himself sentenced to be torn apart by wild horses. The men were slaughtered in such numbers that the women went out to help each other sow the fields. At sunset they returned, hand in hand, singing a melancholy lament, until this too was prohibited by Spanish law. All musical instruments were to be destroyed; the use of the Quichua language was forbidden; women were ordered not to spin as they walked; distinctive customs were to be laid aside. All lapsed into spiritless dullness. The air of desolation spread. The Indians of Peru are a silent people trained by cold and cutting winds. They bite the end of their ponchos to show anger and live to an immense age. Their thoughts turn backwards. They grind their teeth on the same hard corn kernels as formerly and drink the same corn-brandy; they carry about as talismans little effigies of llamas found in the graves of their ancestors and throw their criminals over the same lofty precipices. The juice of the red thorn-apple leads them into ecstasy, the only high light of their existence, for by means of it they communicate with the spirits of their ancestors. The only passion they have brought with them through the centuries is remembrance of the past. The thorn-apple is called huaca cachu, the plant of the grave. The Indians squat about in groups with their little gourds of chicha. There is no laughing. The mummy-like babies do not cry. The lake on whose banks they live contains no fish. No worm, no insect, inhabits its banks. But there is a spirit which broods from the mountain above. He will lighten the burden of the traveler who seeks the mountain-top and presents him offerings in the depths of night. The achachibas or piles of stones are witness to his gracious power. Between two mountain-tops lies a steel-colored lake shimmering in its stone basin. The Indians come here to beg for fire-water. They pour in brandy, standing on a peak while making their libation to the rain-god, and then leave without a word. Immediately the rain pours. Only their religious festivals recall Inca feast days. Christianity has never been able to abolish the bacchanales of former times; it has merely changed their names. The call of triumph, haylli, has been changed to Hallelujah, Christian anthems are set to Indian tunes, IHS has been engraved on the stone doorways of antiquity. Over the shrines outside the churches are effigies of sun and moon. Above the megalithic fortress of Sachsahuaman three crosses preside where the banners once indicated the dwelling of the Children of the Sun. Indians still salute the Sun temple on first entering Cuzco, though the nave of the Dominican church stands upon the spot where the Sun was worshipped in golden chambers, its Christian walls built of mammoth stones rolled together for the glory of the Sun. This superstructure typifies the methods of the missionary priests. A wooden llama filled with fire-crackers is exploded on Good Friday. By the roadside, an Indian in a grotesque mask, with a feather crown and bells on his arms and legs, leaps in fantastic bounds to celebrate the day of the Holy Cross. A picture of the Virgin is carried about on her Ascension Day. The Indians, dressed in the masks of wild animals and multicolored feathers with bits of savage embroidery on their loose garments, dance about her to fifes and drum-beats and rattles of beans and snail-shells. Wild dances, horn-blowing, ugly voices screaming, and rattling tin — these heathen orgies swarm at the feet of effigies of Christ. The Indian has to be content with the scanty earnings he can get from the transport of heavy burdens and from the wool of his llamas. By chewing coca he is able to run all day before the rider. His world is the valley where he lives. His occupation does not lead him to the mountain-top above, nor does his thought soar as far. His gloom sulks in his dress and manner of life, even in his songs and dances. When he reaches his little smoky hut, he eats his frozen and pressed potato, plays a wee tune on his quena and goes to sleep. Self-sufficient because in need of nothing, the llama is the interpretation of the Indian. Both are products of the soil, like the yareta moss and the birds which swim in the icy water. The dark-eyed llamas, with red-woolen tassels in their ears, move slowly across the icy plateau. Could anything equal the dignity of a llama, his serenity, his hauteur? Why not? He knows he is indispensable. There is no one to take his place. His wool furnishes clothing, his skin leather, his flesh food, his dung fuel, and he is a beast of burden where no other can live on the bare, breathless heights. In return, he asks no shelter, warm beneath his shaggy coat. He asks no food, for he grazes on the stiff ychu grass as he journeys along. He needs no shoes, no harness, and even provides, himself, the wool for the homespun bags lying upon his back. When there is no water, he carries in bags made of his own skin what is necessary for man. Nor do his benefactions end here. The llama furnished the mystery-loving Spaniards with that strange bezoar stone which, on account of its miraculous endowments, they placed in the list with emeralds, pearls, turquoises, and other precious stones from Peru. Is it astonishing that the llama makes his own rules of conduct and exacts entire consideration of them? Disobedience he indicates in a way not to be forgotten! And yet such is his docility that dozens are often kept within bounds by a single thread stretched around them breast high, — rugged little mountain beasts herded with worsted! Usually so gentle, if a llama. is annoyed he becomes revengeful and useless. He never will hurry, for supplying his own food he must graze when opportunity offers. He will not be overloaded. One hundred pounds he will cheerfully carry, but with more than that he sits down like a camel, dreamily chewing his cud, and can be neither forced nor persuaded to rise. In speaking of the alpaca, cousin of the llama, Father Acosta said that "the only remedy is to stay and sit down by the paco, making much on him, until the fit be passed, and that he rise; and sometimes they are forced to stay two or three hours." The little variegated herd, with expressions of mild surprise, step daintily along as if walking on eggs, following at even distances, each moving with authority of a whole procession. If frightened, they huddle into a compact group, craning their long necks toward the center. Then they look you wistfully in the face for minutes at a time without moving. The halter of the leader is embroidered, and small streamers flutter from it. Most of the llamas have tassels in their ears, or little pendants or bells. Thus they file across the snow-covered cordillera.  Llamas at the Falls of Morococha At night when they sink on to the puna at their journey's end, a faint murmur like many aeolian harps is wafted into the perfect stillness of the frosty night. It is the llamas' appreciation of rest. |